CSLH Bulletin 59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, the Hanesyn Hên

04 Guy_Studia Celtica 50 06/12/2016 09:34 Page 69 STUDIA CELTICA, L (2016), 69 –105, 10.16922/SC.50.4 A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, The Hanesyn Hên BEN GUY Cambridge University In 1658, William Maurice made a catalogue of the most important manuscripts in the library of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt, in which 158 items were listed. 1 Many copies of Maurice’s catalogue exist, deriving from two variant versions, best represented respec - tively by the copies in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales [= NLW], Wynnstay 10, written by Maurice’s amanuenses in 1671 and annotated by Maurice himself, and in NLW Peniarth 119, written by Edward Lhwyd and his collaborators around 1700. 2 In 1843, Aneirin Owen created a list of those manuscripts in Maurice’s catalogue which he was able to find still present in the Hengwrt (later Peniarth) collection. 3 W. W. E. Wynne later responded by publishing a list, based on Maurice’s catalogue, of the manuscripts which Owen believed to be missing, some of which Wynne was able to identify as extant. 4 Among the manuscripts remaining unidentified was item 33, the manuscript which Edward Lhwyd had called the ‘ Hanesyn Hên ’. 5 The contents list provided by Maurice in his catalogue shows that this manuscript was of considerable interest. 6 The entries for Hengwrt 33 in both Wynnstay 10 and Peniarth 119 are identical in all significant respects. These lists are supplemented by a briefer list compiled by Lhwyd and included elsewhere in Peniarth 119 as part of a document entitled ‘A Catalogue of some MSS. -

Design & Access Statement

DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT Full planning application for the erection of polytunnels and all associated works Prepared for Maelor Forest Nurseries October 2020 Roger Parry & Partners LLP www.rogerparry.net [email protected] Tel: 01691 655334 1 D & A Statement| Roger Parry & Partners LLP Applicant’s Details Maelor Forest Nurseries Full planning application for the Maelor Forest Nurseries Ellesmere Road erection of polytunnels and all Whitchurch SY13 3HZ associated works Local Planning Authority Design & Access Statement Wrexham County Borough Council Planning Services October 2020 16 Lord Street Wrexham LL11 1LG Roger Parry & Partners LLP Design and Access Statement as required by Section 42 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 Roger Parry & Partners LLP The Estates Office 20 Salop Road Oswestry Shropshire SY21 2NU Tel: 01691 655334 Fax: 01691 657798 Email: [email protected] www.rogerparry.net Ref: DAS V1 i D & A Statement| Roger Parry & Partners LLP Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 PROPOSAL ................................................................................................................................................. 4 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF THE SITE AND ITS CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 4 3.1 PHYSICAL SITUATION – THE CONTEXT ................................................................................................................ -

A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, the Hanesyn Hên

04 Guy_Studia Celtica 50 06/12/2016 09:34 Page 69 STUDIA CELTICA, L (2016), 69 –105, 10.16922/SC.50.4 A Lost Medieval Manuscript from North Wales: Hengwrt 33, The Hanesyn Hên BEN GUY Cambridge University In 1658, William Maurice made a catalogue of the most important manuscripts in the library of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt, in which 158 items were listed. 1 Many copies of Maurice’s catalogue exist, deriving from two variant versions, best represented respec - tively by the copies in Aberystwyth, National Library of Wales [= NLW], Wynnstay 10, written by Maurice’s amanuenses in 1671 and annotated by Maurice himself, and in NLW Peniarth 119, written by Edward Lhwyd and his collaborators around 1700. 2 In 1843, Aneirin Owen created a list of those manuscripts in Maurice’s catalogue which he was able to find still present in the Hengwrt (later Peniarth) collection. 3 W. W. E. Wynne later responded by publishing a list, based on Maurice’s catalogue, of the manuscripts which Owen believed to be missing, some of which Wynne was able to identify as extant. 4 Among the manuscripts remaining unidentified was item 33, the manuscript which Edward Lhwyd had called the ‘ Hanesyn Hên ’. 5 The contents list provided by Maurice in his catalogue shows that this manuscript was of considerable interest. 6 The entries for Hengwrt 33 in both Wynnstay 10 and Peniarth 119 are identical in all significant respects. These lists are supplemented by a briefer list compiled by Lhwyd and included elsewhere in Peniarth 119 as part of a document entitled ‘A Catalogue of some MSS. -

Final SEA Screening Statement

Formatted: Cover text Final Water Resources Management Plan 2019 SEA Screening Statement ________________________________ ___________________ Final Report for Hafren Dyfrdwy ED62813 | Issue Number 4 | Date 26/09/2019 Ricardo Energy & Environment Final Water Resources Management Plan 2019 SEA Screening Statement | i Customer: Customer Contact: Hafren Dyfrdwy Dr. Mohsin Hafeez Ricardo Energy & Environment Customer reference: Enterprise House, Lloyd Street North, Manchester, United Kingdom. M15 6SE ED62813 Confidentiality, copyright & reproduction: e: [email protected] This report is the Copyright of Hafren Dyfrdwy/Ricardo Energy & Environment. It has been prepared by Ricardo Energy & Environment, a trading name of Ricardo-AEA Ltd, Author: under contract to Hafren Dyfrdwy. The contents of this report may not be reproduced in whole or Ben Gouldman, Ed Fredenham and Mohsin in part, nor passed to any organisation or person Hafeez without the specific prior written permission of Hafren Dyfrdwy. Ricardo Energy & Environment Approved By: accepts no liability whatsoever to any third party Mohsin Hafeez for any loss or damage arising from any interpretation or use of the information contained Date: in this report, or reliance on any views expressed therein. 26 September 2019 Ricardo Energy & Environment reference: Ref: ED62813- Issue Number 4 Ricardo in Confidence Ref: Ricardo/ED62813/Issue Number 4 Ricardo Energy & Environment Final Water Resources Management Plan 2019 SEA Screening Statement | 1 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................2 -

The Story of a Quiet Country Parish, Being Gleanings of the History of Worthenbury, Flintshire

3 1833 01941 3183 THE STORY OF A QUIET Gc 942.935019 W933p 1335236 ge:nz:."<l.c.3v col.l.ectiom \ : THE STORY OF A QUIET COUNTRY PARISH. BEING GLEANINGS OF THE HISTORY OF WORTHENBURY. FLINTSHIRE. BY THE RECTOR, THE REV. SIR T. H. GRESLEY PULESTON, BART, Xon^on THE ROXBURGHE PRESS, 3, VICTORIA STREET, WESTMINSTER. A. M. ROBINSON & SON, PRINTERS, DUKE STREET, BRIGHTON. CITY offices: I, LOMBARD COURT. «^ 1335236 TO THE SACRED MEMORIES OF THE PAST PREFACE Having inherited some notes on the Parish of Worthenbury, which I only recently read, I determined, with these and other means within my reach, to write all that I could gather of the history of my parish, knowing, however, perfectly well, how imperfect my work must be, yet bearing in mind Machiavelli's saying that " it was better to do things badly than not to do them at all." T. H. G. P. C(?c Slonj of a (Duiet Countrj) Parisl?, BEING GLEANINGS OF The History of Worthenbury, Flintshire. Although Worthenbury does not appear to have been the scene of any great historical events, yet I hope to put togfether some gatherings which may have interest for those who know it and love it. It is situated on the river Dee, is bounded on the south by Shropshire and on the north by Cheshire, and forms a part of the Hundred of Maelor, or Maelor Saesneo', to distinguish it from Maelor Cymraig in Denbighshire ; it is in the county of Flint, though separated from the main part of it by the portion of the county of Denbigh in the neigh- bourhood of Wrexham, through which one must pass for live or six miles before again touching Flint- shire. -

PILGRIMS REACH the ENGLISH MAELOR (Once FLINTSHIRE DETACHED)

PILGRIMS REACH THE ENGLISH MAELOR (once FLINTSHIRE DETACHED) COULD YOU JOIN US TO WELCOME, WALK OR JOIN FOR PRAYER WHEN PILGRIMS CALL NEAR YOU? THE STORY SO FAR…. Walk 1: Pilgrims approach Holt across the fields from Lavister / Rossett towards their first ancient bridge across the Dee between Farndon & Holt. Pilgrims welcomed with hospitality and join in prayer at the ancient church of St Chad, Holt. Walk 2: Having set out across ancient bridge at Holt the pilgrims are met by friends at Crewe by Farndon Methodist chapel and then make their way across the fields to Worthenbury church tower Pilgrims are welcomed with hospitality offered by members of the congregation outside the 18th century church at Worthenbury, then all join for devotions & prayers together ‘Guide me Oh thou great redeemer, pilgrim….’ Pilgrims kept on the straight and narrow as they make their way across the fields to this journey’s end at Bangor is y coed close by another ancient church and bridge across the River Dee. WALK 3: The pilgrims congregate at Bangor is y coed where our second bridge crosses the River Dee. In the ancient church we start the day with prayer, close by where monks once prayed in a monastery founded in or around 560AD by Saint Dunod. It was not a long-lived foundation, but it was famous – it is recorded that the Abbot & 7 Bishops from the ‘Great Abbeys’ at Bangor-on-Dee were present at the ‘Council of the Oak’ when Augustine of Canterbury landed on our shores (597AD) (we are indebted to Father Chris Howard of St Mary’s Cathedral, Wrexham for this information) Pilgrims head east across the English Maelor, toward the English border near Threapwood, led by local resident Dave Paton (webmaster of www.threapwood.org ), and on towards a warm welcome at Tallarn Green Methodist Chapel. -

Download Complete Issue

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England founded in 1913). EDITOR: Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 5 No.5 November 1994 CONTENTS Editorial and Notes ............................................ 237 Separation In and Out of the Church: the Consistency of Barrow and Greenwood by Patrick Collinson, C.B.E., MA., Ph.D., D.Litt., .FBA. 239 Philip Henry and London by Geoffrey F Nuttall, MA., D.D., F.B.A. 259 The Scottish Evangelical Awakening of 1742 and the Religious Societies by Kenneth B.E. Roxburgh, B.A., MTh. 266 The Newport Pagnell Academy 1782-1850 by Marilyn Lewis, B.A., MA. 273 'Our School of the Prophets'. The Presbyterian Church in England and its College 1844-1876 by David Cornick, MA., B.D., Ph.D., A.K.C. 283 The First Moderators: 1919 by E.P.M Wollaston, MA. 298 Reviews by Stephen Orchard and Alan P.F Sell . 301 EDITORIAL Anniversaries are for Historians what Heritage is for Conservationists - heady opportunities for getting things wrong in high profile, to be enjoyed as popular means to a greater end. This issue might appear to be unusually anniversary-conscious for a normally sober journal. We have the quater centenary of the deaths of Barrow and Greenwood, the sesquicentenary of the birth of what is now Westminster College, Cambridge, and the seventy-fifth anniversary of English Congregationalism's first moderators. Professor Collinson mildly describes 1593 as a vindictive year. More might be said for 1844, which 237 238 EDITORIAL also produced the YMCA (in large part a Congregational artefact with Presbyterian dressings) and the Cooperative Movement. -

Some Hampshire Rectors

109 SOME HAMPSHIRE RECTORS. By MRS. COPE. To find any connection between Hampshire and North Wales is .very unexpected, but in this world the unexpected generally , happens. There is in North Wales a peculiar part of it adjoining England which figures on the map as a detached portion of Flintshire, but which is known locally as Maelor Saesneg, or English Maelor. The old families who lived there for genera- tions were all of Norman origin; to this day the locality prides itself on not knowing a word 'of Welsh—the only -Welsh is the Post Office notices, which no one pretends to understand. Close to Wrexham, but not actually in English Maelor, is the pretty village of Gresford. Both Wrexham and Gresford are celebrated for the fine towers of their churches; that of Wrexham ranks as one of the " Seven Wonders of Wales." Among the oldest families in English Maelor was Pyvelisdon or Puleston, always pronounced Pilston, whose origin was Pyvelisdon in Normandy, whence they settled near Newport in Shropshire, calling a place after their old Norman home, and in the 13th century they moved from Salop to Maelor Sasneg, to Emral, or Embershall, where they lived, father and son, through long cen- turies until the family died out in the male line in the time of George III. There were many branches of the family. Some yet remained in Shropshire, others found homes round the neighbourhood of Emral, and another branch came to Hampshire and settled there in the 16th and 17th century. How this came about is evident. -

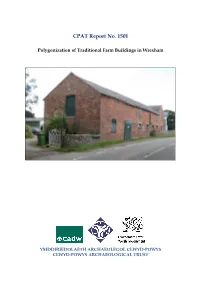

CPAT Report No. 1501

CPAT Report No. 1501 Polygonization of Traditional Farm Buildings in Wrexham YMDDIRIEDOLAETH ARCHAEOLEGOL CLWYD-POWYS CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST Client name: Cadw CPAT Project No: 2025 Project Name: Farms and Farmsteads Grid Reference: n/a County/LPA: Wrexham CPAT Report No: 1501 Issue No: Report status: Prepared by: Checked by: Approved by: Paul Belford Abi McCullough Chris Martin Paul Belford Heritage Management Principal Curatorial Officer Director Archaeologist Date: 27 March 2017 Date: 27 March 2017 Date: 27 March 2017 Bibliographic reference: McCullough, A E, Watson, S W and Martin, C H R, 2017, Polygonization of Traditional Farm Buildings in Wrexham, CPAT Report 1501 Cover: Building at Little Overton Farm, PRN 129289, CPAT photograph 2940-IMG_1050. A non-listed building recorded by the pilot project, and visited during field verification. YMDDIRIEDOLAETH ARCHAEOLEGOL CLWYD-POWYS CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR, United Kingdom +44 (0) 1938 553 670 [email protected] www.cpat.org.uk ©CPAT 2017 The Clwyd‐Powys Archaeological Trust is a Registered Organisation with the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists YMDDIRIEDOLAETH ARCHAEOLEGOL CLWYD-POWYS CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR, United Kingdom +44 (0) 1938 553 670 [email protected] www.cpat.org.uk ©CPAT 2017 The Clwyd‐Powys Archaeological Trust is a Registered Organisation with the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists CPAT Report No 1501 Polygonization of Traditional Farm Buildings in -

Cheshire in Domesday Book

TRANSACTIONS. CHESHIRE IN DOMESDAY BOOK. By J. Brownbill. Read 3oth November, 1899. HE study of a county in the great survey made T by the Conqueror in 1086 may be undertaken from any one of a great variety of motives. So far as the Cheshire portion is concerned, national history is not touched upon except by a reference to the rebellion of the Welsh king, Griffith, in 1063 ; but the subjugation of the county by Wil liam in 1070 is witnessed grimly enough by the very general "waste" in which the manors lay " when the Earl received them," a "waste" from which they had not altogether recovered sixteen years afterwards. Those who are interested in the ancient popular government will notice that the various hundreds are named from some hill, or stone, or tree at which the " free men " assembled for law and judgment. The county meeting was probably at Chester; there are several instances in which its decisions are recorded, chiefly in cases 2 Cheshire in Domesday Book. where the Church had lost property. 1 One manor (Dunham on the Hill) was held "in paragio," which Mr. Beamont explains as meaning that it was divi sible equally among all the children (or heirs) on the owner's death. Then again, the laws as to the city of Chester, with which the county record opens, and those as to the making of salt in the " Wiches " with which it closes, might each form the hasis of a substantial treatise if they were expounded at length. Others will find a congenial field of study in the names of the English proprietors and the Normans who displaced them. -

Downloading Material Is Agreeing to Abide by the Terms of the Repository Licence

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in: The English Historical Review Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa43594 _____________________________________________________________ Paper: Cavell, E. (2018). Widows, Native Law and the Long Shadow of England in Thirteenth-Century Wales*. The English Historical Review http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cey335 _____________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ 1 Widows, Native Law and the Long Shadow of England in Thirteenth- Century Wales In our familiarity with Robert Bartlett’s persuasive model of medieval Latin Christendom,1 at once increasingly homogeneous and aggressively expansionist, we are apt to forget the contribution of the peripheries to the core’s outward thrust and to their own domination and transformation. In our traditional focus, too, on warriors, peasant farmers and churchmen, we are equally inclined to overlook women in the ‘making of Europe’. -

NLCA14 Maelor - Page 1 of 6

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA14 MAELOR © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 www.naturalresources.wales NLCA14 Maelor - Page 1 of 6 Maelor Saesneg – Disgrifiad Cryno Maelor Saesneg yw’r tamaid hwnnw o diriogaeth Cymru sy’n ymwthio i Wastadedd Caer. Y mae hi, a’r rhimyn o dir gwastad ar lannau Dyfrdwy ymhellach i’r gogledd, yn debycach, ar sawl ystyr, i rannau o Swydd Amwythig neu Swydd Gaerllion nag i fryniau Maelor Gymraeg i’r gorllewin. Gwelodd ganrifoedd o lanw a thrai dylanwadau Cymreig a Seisnig, a cheir yma gymysgedd o enwau lleoedd Cymraeg a Saesneg: rhai’n wreiddiol, eraill wedi’u haddasu o’r naill iaith i’r llall. Yn rhai mannau, mae’r caeau a’r patrwm anheddiad wedi ffosileiddio tirwedd Ganoloesol, gyda ffosydd amddiffynnol, a meysydd agored gydag amaethyddiaeth “cefnen a rhych”. Mae rhannau o’r dirwedd hŷn yma yn cael eu colli gyda newidiadau ac arferion ffermio modern: ond mae’r ardal, yn enwedig yr hanner gorllewinol, wedi goroesi’n rhyfeddol, ac yn heddychlon a llonydd. Mae’n anodd credu mewn cyfarfod ras ym Mangor Is-coed nad yw cyn-bentrefi glofaol Johnstown a Rhosllannerchrugog ym Maelor Gymraeg, ac ystâd ddiwydiannol Wrecsam (y fwyaf yn Ewrop, debyg) ond ychydig filltiroedd i ffwrdd. Mae’n debyg bod yr ardal yn fwy adnabyddus am ei llynnoedd a’i chorsydd, ac am ei mawnogydd. Summary description The area includes ‘English Maelor’, that short sleeve of Welsh territory protruding into Cheshire Plain west of the Dee and parts of ‘Welsh Maelor’ to the east.