How Film and Tv Music Communicate Vol Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You're Listening to Ocean Currents, a Podcast Brought to You by NOAA's Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary

1 July 7th, 2014, oc070714.mp3 Free Diving and El Nino 2014 Jennifer Stock, Francesca Koe, Logan Johnson Jennifer Stock: You're listening to Ocean Currents, a podcast brought to you by NOAA's Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary. This radio program was originally broadcast on KWMR in Point Reyes Station, California. Thanks for listening! Welcome to another edition of Ocean Currents, I'm your host, Jennifer Stock. On this show I talk with scientists, educators, explorers, policy-makers, ocean enthusiasts, adventurers and more, all uncovering and learning about the mysterious and vital part of our planet: the blue ocean. I bring this show to you monthly on KWMR from NOAA's Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, one of four national marine sanctuaries in California all working to protect unique and biologically diverse ecosystems. Cordell bank is located just offshore of the KWMR listening radius off the Marin-Sonoma coast, and it's thriving with ocean life above and below the surface. The ocean holds so many mysteries to us: the habitats, the life, the mysterious ways it moves and mixes, its temperatures, its ability to absorb carbon dioxide. And as a species-- as humans-- we've made great strides on being able to enter it and see it below the surface with technology aiding greatly. Before scuba was invented we were limited by our breath to explore underwater, and this is how humans first accessed the sea, and today we still access the sea this way. If you've ever held your breath underwater before you have been free diving. -

COURSE CATALOG 2016-2017 Academic Calendar

COURSE CATALOG 2016-2017 Academic Calendar . 4 Academic Programs . 46 About LACM . .. 6 Performance LACM Educational Programs . 8 Bass . 46 CONTENTS Administration . 10 Brass & Woodwind . .. 52 Admissions . 11 Drums . .. 58 Tuition & Fees . 13 Guitar . 64 Financial Aid . 18 Vocal. 70 Registrar . 22 Music Composition International Student Services . 26 Songwriting . 76 Academic Policies & Procedures . 27 Music Production Student Life . 30 Composing for Visual Media . 82 Career Services . .. 32 Music Producing & Recording . 88 Campus Facilities – Security. 33 Music Industry Rules of Conduct & Expectations . 35 Music Business . 94 Health Policies . 36 Course Descriptions . 100 Grievance Policy & Procedures . .. 39 Department Chairs & Faculty Biographies . 132 Change of Student Status Policies & Procedures . 41 Collegiate Articulation & Transfer Agreements . 44 FALL 2016 (OCTOBER 3 – DECEMBER 16) ACADEMIC DATES SPRING 2017 (APRIL 10 – JUNE 23) ACADEMIC DATES July 25 - 29: Registration Period for October 3 - October 7: Add/Drop January 30 - February 3: Registration Period for April 10 - April 14: Add/Drop Upcoming Quarter Upcoming Quarter October 10 - November 11: Drop with a “W” April 17 - May 19: Drop with a “W” August 22: Tuition Deadline for Continuing Students February 27: Tuition Deadline for November 14 - December 9: Receive a letter grade May 22 - June 16: Receive a letter grade October 3: Quarter Begins Continuing Students November 11: Veterans Day, Campus Closed April 10: Quarter Begins November 24: Thanksgiving, Campus Closed May 29: Memorial Day, Campus Closed November 25: Campus Open, No classes. June 19 - 23: Exams Week December 12-16: Exams Week June 23: Quarter Ends December 16: Quarter Ends December 24 - 25: Christmas, Campus Closed December 26: Campus Open, No classes. -

International Production Notes

INTERNATIONAL PRODUCTION NOTES PUBLICITY CONTACT Julia Benaroya Lionsgate +1 310-255-3095 [email protected] US RELEASE DATE: SEPTEMBER 28, 2018 RUNNING TIME: 89 MINUTES TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTION INFORMATION ..................................... 4 ABOUT THE CAST ................................................ 14 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS ..................................... 18 END CREDITS ...................................................... 26 3 PRODUCTION INFORMATION In this terrifying thrill ride, college student Natalie is visiting her childhood best friend Brooke and her roommate Taylor. If it was any other time of year these three and their boyfriends might be heading to a concert or bar, but it is Halloween which means that like everyone else they will be bound for Hell Fest – a sprawling labyrinth of rides, games and mazes that travels the country and happens to be in town. Every year thousands follow Hell Fest to experience fear at the ghoulish carnival of nightmares. But for one visitor, Hell Fest is not the attraction – it is a hunting ground. An opportunity to slay in plain view of a gawking audience, too caught up in the terrifyingly fun atmosphere to recognize the horrific reality playing out before their eyes. As the body count and frenzied excitement of the crowds continue to rise, he turns his masked gaze to Natalie, Brooke, Taylor and their boyfriends who will fight to survive the night. CBS FILMS and TUCKER TOOLEY ENTERTAINMENT present a VALHALLA MOTION PICTURES production HELL FEST Starring Amy Forsyth, Reign Edwards, Bex Taylor-Klaus and Tony Todd. Casting by Deanna Brigidi, CSA and Lisa Mae Fincannon. Music by Bear McCreary. Costume Designer Eulyn C. Hufkie. Editors Gregory Plotkin, ACE and David Egan. -

Dive 010 - Sea Docs

Dive 010 - Sea Docs Our last collection of Sea Genre films focusing on the watery realms of The Soundtrack Zone may be classified as films in the Sea Documentary genre or, for short, Sea Docs. Two early examples of scores for a Sea Doc film were those composed by Paul J. Smith for two Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventures films: Beaver Valley (1950) and Prowlers of the Everglades (1953). A Disneyland LP (WDL-4011 – released in 1975) included the following tracks from those two films: Beaver Valley (7:15) - Beaver Valley Theme - Baby Ducks - Beaver Romance - Salmon Run – Otters Prowlers of the Everglades (4:09) - Alligators - Swamp Deluge - Otters And Gators LP In 1956, Walt Disney’s Disneyland WDL-4006 LP presented Paul J. Smith’s score for another True-Life Adventure film, Secrets of Life. One of the album’s suites, “Under The Sea And Along The Shore,” includes several underwater-related tracks: Decorator Crab, Jellyfish, Angler Fish, and Fiddler Crabs (04:21) LP Three years later, in 1959, Walt Disney released a short film titled Mysteries of the Deep (23:55). Three of these films – Beaver Valley, Prowlers of the Everglades, and Mysteries of the Deep are available on DVD (see DVD 1 photo below). Secrets of Life is included on DVD 2 (see photo below). DVD 1 DVD 2 Unfortunately none of the scores for these Walt Disney underwater-related films have been commercially issued on CD. Fortunately, the scores of many subsequent Sea Docs films have been released over the years on LP and/or CD. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

No Limits Freediving

1 No Limits Freediving "The challenges to the respiratory function of the breath-hold diver' are formidable. One has to marvel at the ability of the human body to cope with stresses that far exceed what normal terrestrial life requires." Claes Lundgren, Director, Center for Research and Education in Special Environments A woman in a deeply relaxed state floats in the water next to a diving buoy. She is clad in a figure-hugging wetsuit, a dive computer strapped to her right wrist, and another to her calf. She wears strange form-hugging silicone goggles that distort her eyes, giving her a strange bug-eyed appearance. A couple of meters away, five support divers tread water near a diving platform, watching her perform an elaborate breathing ritual while she hangs onto a metal tube fitted with two crossbars. A few meters below the buoy, we see that the metal tube is in fact a weighted sled attached to a cable descending into the dark-blue water. Her eyes are still closed as she begins performing a series of final inhalations, breathing faster and faster. Photographers on the media boats snap pictures as she performs her final few deep and long hyperventilations, eliminating carbon dioxide from her body. Then, a thumbs-up to her surface crew, a pinch of the nose clip, one final lungful of air, and the woman closes her eyes, wraps her knees around the bottom bar of the sled, releases a brake device, and disappears gracefully beneath the waves. The harsh sounds of the wind and waves suddenly cease and are replaced by the effervescent bubbling of air being released from the regulators of scuba-divers. -

Chapter 2 T H E S U B T L E T I E S, I N T R I C a C I E S a N D

How Film & TV Music Communicate – Vol.2 Text © Brian Morrell 2013 Chapter 2 T H E S U B T L E T I E S, I N T R I C A C I E S A N D E X Q U I S I T E T E N S I O N S O F T V M U S I C In this chapter we will examine the music for some notable television dramas and documentaries, all of which have, to varying degrees, subtlety, introspection and /or elements of minimalism as hallmarks of their identity. This needn’t always mean ‘quiet and closed-off’ but that the composers in each case have scored the films using a degree of restraint and sensitivity. In all cases the music has been pivotal in defining the projects commercially and creatively. The television dramas and documentaries analysed are: Lost (Michael Giacchano) The Waking Dead (Bear McCreary) Midnight Man (Ben Bartlett) Twin Peaks (Angelo Badalmenti) Silent Witness (John Harle) Inspector Morse (Barrington Pheloung) Deep Water (Harry Escott) Inspector Lynley Mysteries (Andy Price) Ten Days to War (Daniel Pemberton) Red Riding (Adrian Johnston) Dexter (Rolf Kent and Daniel Licht) Lost Michael Giacchano Lost is an iconic and successful television series which aired between 2004 and 2010. It follows the lives of survivors of a plane crash on a mysterious tropical island somewhere in the South Pacific. Episodes typically feature a storyline on the island as well as a secondary storyline from another point in a character’s life. The enormously evocative and expressive music for Lost is striking both in terms of its style and its narrative function. -

ODYSSEY LP's- Price (Expires 8/31,76) S1 99 Pe Calif

These same qualities pervade the score mitted performance by Elmer Bernstein LIVE OPERA TAPES. TREMENDOUS SELECTION for Vincent Minnelli's The Bad and the SATISFACTION GUARANTEED. FREE CATALOGUE. C and orchestral forces that sounda great HANDELMAN, 34-10 75th ST., JACKSON HTS. N.Y.C. Beautiful (1952). The "Acting Lesson" se- deal larger than those heard on previous 11372. quence (cut from the film), for instance, has Film Music Collection recordings. Now if "SOUNDTRACKS, SHOW, NOSTALGIA & JAZZ- a transparent poignancy similar to that in they can just learn to spell Rozsa'sname FREE Catalog & Auction List-A-1 Record Finders, P.O. many parts of Forever Amber. In this score correctly on the album cover.... R.S.B. Box 75071-H, L.A. CAL. 90075." Raksin shows himself to have the same CLASSICS FOR CONNOISSEURS: WE OFFER AN AR- deep roots in Americana that can be found, RAY OF CLASSICAL IMPORTS FROM ALL OVER THE in different veins, in composers such as WORLD. WE HAVE CONTACTS WHICH GIVE US AN EX- Gershwin and Copland. This is made evi- HENRY MANCINI: A Concert of Film Music. CLUSIVE TO BRING TO OUR CUSTOMERS RARE AND dent immediately in the bluesy quality of London Symphony Orchestra, Henry Man- HARD -TO -FIND CLASSICAL RECORDINGS-OUR SPE- cini, CIALTY. WE GUARANTEE THE BEST SERVICE POS- the main theme; but it also appears in a less cond. [Joe Reisman, prod.] RCA ARL SIBLE ON ALL ORDERS. COPIES OF THREE BULLE- tangible, more "classically" oriented fash- 1-1379, $6.98. Tape:WV ARK 1-1379,$7.95; TINS-S1. -

Aktuelle Rezension

Aktuelle Rezension French Saxophone - 20th Century Music for Saxophone & Orchestra aud 97.500 EAN: 4022143975003 4022143975003 www.musicweb-international.com (Rob Barnett - 21.05.2004) Here is a provocatively attractive and varied collection that should appeal to saxophone buffs as well as enthusiasts of these composers and this style-genre. With the exception of the Debussy these are all uncommon works and will attract interest ... and more. The Tomasi shows Tassot as a soloist able to coax honey and amber from the sax. The legato phrasing is notable slightly coloured with a jazzy voice. The music has the motion of sea-wrack and deep green tones. The second episode is more animated with a ‘Bolero’ stomp. The brass can be scaldingly Baxian and the boiling climaxes at 7.01 and 11.15 are redolent of La Valse (again a Ravel cross-reference). Soon we return to the warbling and rough-rolling brass - a little like Messiaen meets Bax. There are only two movements the second of which starts with a sinister Baxian chase. This is extremely effective music also reminding me of the music of Louis Aubert (the superb Tombeau de Chateaubriand - hear it on Marco Polo) and the melodramatic Bernard Herrmann. Tomasi is well worth dedicated exploration and persistence as the Lyrinx CD (LYR 227) also reviewed here further bears out. I have been working on a review of his gorgeous opera Don Juan for several months now. I was much looking forward to the Caplet having heard his scorchingly imaginative and tragic Epiphanie for cello and orchestra last year. -

Knowledge Organiser

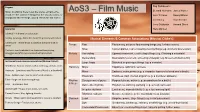

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000

The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000: A Performative and Analytical Study, with a Catalogue Raisonné of the Extant Works Analytical Study: The Contest Works for Trumpet and Cornet of the Paris Conservatoire, 1835-2000: A Study of Instrumental Techniques, Forms and Genres, with a Catalogue Raisonné of the Extant Corpus By Brandon Philip Jones ORCHID ID# 0000-0001-9083-9907 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2018 Faculty of Fine Arts and Music The University of Melbourne ABSTRACT The Conservatoire de Paris concours were a consistent source of new literature for the trumpet and cornet from 1835 to 2000. Over this time, professors and composers added over 172 works to the repertoire. Students and professionals have performed many of these pieces, granting long-term popularity to a select group. However, the majority of these works are not well-known. The aim of this study is to provide students, teachers, and performers with a greater ability to access these works. This aim is supported in three ways: performances of under-recorded literature; an analysis of the instrumental techniques, forms and genres used in the corpus; and a catalogue raisonné of all extant contest works. The performative aspect of this project is contained in two compact discs of recordings, as well as a digital video of a live recital. Twenty-six works were recorded; seven are popular works in the genre, and the other nineteen are works that are previously unrecorded. The analytical aspect is in the written thesis; it uses the information obtained in the creation of the catalogue raisonné to provide an overview of the corpus in two vectors. -

Ebook Download Life in Cold Blood

LIFE IN COLD BLOOD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sir David Attenborough | 288 pages | 06 Dec 2007 | Ebury Publishing | 9780563539223 | English | London, United Kingdom Life in Cold Blood PDF Book Intention in Law and Society. Get A Copy. Capote writes that Smith recounted later, "I didn't want to harm the man. The cover, which was designed by S. The similarities in colouration between the harmless kingsnake and potentially lethal coral snake are highlighted. The Best Horror Movies on Netflix. Under the Skin discusses the filming of timber rattlesnakes during inclement weather. Listserv Archives. Open Preview See a Problem? Hickock soon hatched the idea to steal the safe and start a new life in Mexico. Metacritic Reviews. Retrieved December 1, After five years on death row at the Kansas State Penitentiary , Smith and Hickock were executed by hanging on April 14, Welcome back. In , 50 years after the Clutter murders, the Huffington Post asked Kansas citizens about the effects of the trial, and their opinions of the book and subsequent movie and television series about the events. Error rating book. Attenborough visits Dassen Island to witness one of the world's greatest concentrations of tortoises — around 5, of them. Other editions. Not only that, but the book is richly illustrated with amazing photographs of these animals in action, many of them the kind of thing you'll never see in real life without the guidance of an expert herpetologist an This is a marvelous book, especially if, like me, you're a reptile lover. Thermal imaging cameras were used to demonstrate the creatures' variable body temperatures, probe cameras allowed access to underground habitats and even a matchbox-sized one was attached to the shell of a tortoise.