Recreation Report and Recommended Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campings Washington Amanda Park - Rain Forest Resort Village - Willaby Campground - Quinault River Inn

Campings Washington Amanda Park - Rain Forest Resort Village - Willaby Campground - Quinault River Inn Anacortes - Pioneer Trails RV Resort - Burlington/Anacortes KOA - Cranberry Lake Campground, Deception Pass SP Anatone - Fields Spring State Park Bridgeport - Bridgeport State Park Arlington - Bridgeport RV Parks - Lake Ki RV Resort Brinnon - Cove RV Park & Country Store Bainbridge Island - Fay Bainbridge Park Campground Burlington Vanaf hier kun je met de ferry naar Seattle - Burlington/Anacortes KOA - Burlington RV Park Battle Ground - Battle Ground Lake State Park Chehalis - Rainbow Falls State Park Bay Center - Bay Center / Willapa Bay KOA Cheney Belfair - Ponderosa Falls RV Resort - Belfair State Park - Peaceful Pines RV Park & Campground - Tahuya Adventure Resort Chelan - Lake Chelan State Park Campground Bellingham - Lakeshore RV Park - Larrabee State Park Campground - Kamei Campground & RV Park - Bellingham RV Park Chinook Black Diamond - RV Park At The Bridge - Lake Sawyer Resort - KM Resorts - Columbia Shores RV Resort - Kansakat-Palmer State Park Clarkston Blaine - Premier RV Resort - Birch Bay State Park - Chief Timothy Park - Beachside RV Park - Hells Canyon Resort - Lighthouse by the Bay RV Resort - Hillview RV Park - Beachcomber RV Park at Birch Bay - Jawbone Flats RV Park - Ball Bayiew RV Park - Riverwalk RV Park Bremerton Colfax - Illahee State Park - Boyer Park & Marina/Snake River KOA Conconully Ephrata - Shady Pines Resort Conconully - Oasis RV Park and Golf Course Copalis Beach Electric City - The Driftwood RV Resort -

2021-23 Washington Wildlife And

2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Critical Habitat Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed March 25, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Simcoe $4,000 Wenas-Cleman Mountian $1,875 McLoughlin Falls West $1,500 Grays River Watershed West Fork Conservation Area $2,000 Rendezvous Additions $1,275 Hunter Mountain $650 Chafey Mountain $590 Leland Conservation Easement $770 Wolf Fork Conservation Easement $497 Golden Doe $1,900 Allen Family Ranch Conservation Easement $36 Total $15,093 2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Farmland Preservation Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed March 25, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Wolf Creek Agricultural Conservation Easement Phase 1 $1,140 Natembea Farm Preservation $430 Hannan Farm $255 Synarep Rangeland $527 Thornton Ranch Agricultural Easement $917 Sunny Okanogan Angus Ranch $205 Upper Naneum Creek Farm $300 Teas Ranch $109 Allen Family Ranch Farmland Preservation Easement $377 VanderWerff Agricultural Conservation Easement $114 Leland Farmland Preservation Easement $241 Hoch Family Farm Agricultural Easement $505 Peyton Ranch Conservation Easement $743 Total $5,862 2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Forestland Preservation Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed March 25, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Little Skookum Inlet Forest Protection Phase 2 $321 Anderson Forestland -

A Lasting Legacy: the Lewis And

WashingtonHistory.org A LASTING LEGACY The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part II By Allen "Doc" Wesselius COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Summer 2001: Vol. 15, No. 2 This is the second in a four-part series discussing the history of the Lewis and Clark expedition and the explorers' efforts to identify, for posterity, elements of the Northwest landscape that they encountered on their journey. Columbia River "The Great River of the West" was on the maps that Lewis and Clark brought with them but the cartographic lore of its upper reach influenced William Clark when he identified the supposed upper fork as "Tarcouche Tesse." British explorer Alexander Mackenzie had called the northern reach of the river "Tacoutche Tesse" in his 1793 journals and map. When the explorers realized they had reached the Columbia River on October 16, 1805, they also discerned that they would not discover the source of the drainage, important as that was for establishing the future sovereignty of the region. After Lewis & Clark determined that there was no short portage route between the Missouri and Columbia rivers, the myth of a Northwest Passage evaporated. The priority for the expedition now was to achieve the primary goal of its mission by reaching the mouth of the Columbia River. American rights of discovery to the Columbia were based on Robert Gray's crossing of the bar in 1792 at the river's discharge into the Pacific. He explored the waterway's western bay and named it "Columbia's River" after his ship, Columbia Rediviva. -

Outdoor Rec Status for Ready Set Gorge May 29

Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area Openings/Closures as of May 29, 2021 Site Status Agency Site Name Remarks May 29 OPRD Ainsworth State Park open CRGNSA - USFS Angels Rest Trailhead open OPRD Angles Rest Trailhead open USACE - The Dalles Dam Avery Park open Day Use Only CRGNSA - USFS Balfour Klickitat open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Boat Launch open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Boat Launch/Cmpg (2 sites)open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Campground open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Doetsch Day Use Area open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Equestrian /Cmpg (2 sites) open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Equistrian TH open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Group Campground open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Lower Picnic Area open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Trail closed Closed temorarily to remove rock fall Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Trailhead open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Upper Picnic Area open Washington State Parks Beacon Rock State Park Woodard Creek Campgroundopen OPRD Benson State Park open Skamania County Parks and RecreationBig Cedar Campground open Port of Klickitat Bingen Marina open ODFW Bonneville Fish Hatchery (Outgrant) closed USACE - Bonneville Dam Bonneville Navigation Lock Visitor Area open Open 1 to 4 daily OPRD Bonneville State Park open USACE - Bonneville Dam Bradford Island Recreation Area open USACE - Bonneville Dam Bradford Island Visitor -

Sanitary Disposals Alabama Through Arkansas

SANITARY DispOSAls Alabama through Arkansas Boniface Chevron Kanaitze Chevron Alaska State Parks Fool Hollow State Park ALABAMA 2801 Boniface Pkwy., Mile 13, Kenai Spur Road, Ninilchik Mile 187.3, (928) 537-3680 I-65 Welcome Center Anchorage Kenai Sterling Hwy. 1500 N. Fool Hollow Lake Road, Show Low. 1 mi. S of Ardmore on I-65 at Centennial Park Schillings Texaco Service Tundra Lodge milepost 364 $6 fee if not staying 8300 Glenn Hwy., Anchorage Willow & Kenai, Kenai Mile 1315, Alaska Hwy., Tok at campground Northbound Rest Area Fountain Chevron Bailey Power Station City Sewage Treatment N of Asheville on I-59 at 3608 Minnesota Dr., Manhole — Tongass Ave. Plant at Old Town Lyman Lake State Park milepost 165 11 mi. S of St. Johns; Anchorage near Cariana Creek, Ketchikan Valdez 1 mi. E of U.S. 666 Southbound Rest Area Garrett’s Tesoro Westside Chevron Ed Church S of Asheville on I-59 Catalina State Park 2811 Seward Hwy., 2425 Tongass Ave., Ketchikan Mile 105.5, Richardson Hwy., 12 mi. N of on U.S. 89 at milepost 168 Anchorage Valdez Tucson Charlie Brown’s Chevron Northbound Rest Area Alamo Lake State Park Indian Hills Chevron Glenn Hwy. & Evergreen Ave., Standard Oil Station 38 mi. N of & U.S. 60 S of Auburn on I-85 6470 DeBarr Rd., Anchorage Palmer Egan & Meals, Valdez Wenden at milepost 43 Burro Creek Mike’s Chevron Palmer’s City Campground Front St. at Case Ave. (Bureau of Land Management) Southbound Rest Area 832 E. Sixth Ave., Anchorage S. Denali St., Palmer Wrangell S of Auburn on I-85 57 mi. -

Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report

Don Hoch Direc tor STATE O F WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSI ON 1111 Israel Ro ad S.W. P.O . Box 42650 Olympia, WA 98504-2650 (360) 902-8500 TDD Telecommunications De vice for the De af: 800-833 -6388 www.parks.s tate.wa.us March 22, 2018 Item E-5: Iron Horse State Park Trail – Renaming Effort/Trail Update – Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This item reports to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission the current status of the process to rename the Iron Horse State Park Trail (which includes the John Wayne Pioneer Trail) and a verbal update on recent trail management activities. This item advances the Commission’s strategic goal: “Provide recreation, cultural, and interpretive opportunities people will want.” SIGNIFICANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Initial acquisition of Iron Horse State Park Trail by the State of Washington occurred in 1981. While supported by many, the sale of the former rail line was controversial for adjacent property owners, some of whom felt that the rail line should have reverted back to adjacent land owners. This concern, first expressed at initial purchase of the trail, continues to influence trail operation today. The trail is located south of, and runs roughly parallel to I-90 (see Appendix 1). The 285-mile linear property extends from North Bend, at its western terminus, to the Town of Tekoa, on the Washington-Idaho border to the east. The property consists of former railroad corridor, the width of which varies between 100 feet and 300 feet. The trail tread itself is typically 8 to 12 feet wide and has been developed on the rail bed, trestles, and tunnels of the old Chicago Milwaukee & St. -

Worthy of Notice

Volume 15, Issue 3 October 2014 Newsletter Worthy of Notice WASHINGTON STATE CHA PTER, LCTHF 2 0 1 4 Fall Chapter meeting D U E S : Beacon Rock State Park, WA S T I L L October 18, 2014 O N L Y $ 1 5 . 0 0 ! “...a remarkable high detached rock Stands in a bottom on the Stard Side near the Just a reminder to lower point of this Island on the Stard. Side about 800 feet high and 400 paces send in your 2014 around, we call the Beaten rock.” - William Clark, October 31, 1805 dues. If your mail- ing or email address Lewis and Clark Park, near Skamania, WA, of the trail to the top of has changed, please fill out the form on would later change their on Saturday, Oct. 18th. Beacon Rock for those page 7 and mail it minds, and rename the We will gather in the who want to participate. along with your Columbia River monolith main parking lot, and the The park also features check. Your mem- with the name it bears to- meeting will begin at 10 other trails for anyone who bership helps support day: Beacon Rock. A.M. The Fall meeting of prefers an easier hike. the activities of the Washington Chapter Yet the prominent the will focus on various throughout the year. geographic feature was Chapter business. Don’t forget—you will need also called Castle Rock for A potluck lunch will to pay a $10 parking fee at many decades, a name follow the meeting at the park, or display a Wash- given by other explorers. -

Work Session Agenda Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission

Work Session Agenda Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission September 19, 2018 Okanogan PUD, 1331 2nd Avenue, Okanogan, WA 98840 Commissioners: Chair Ken Bounds, Vice Chair Cindy Whaley, Secretary Patricia Lantz, Michael Latimer, Diana Perez, Steve Milner and Mark O. Brown. Director: Donald Hoch Time: Opening session will begin as shown; all other times are approximate. Public Comment: This is a work session between staff and the Commission. The public is invited but no public comment will be taken. No decisions will be made by the Commission at the work session. 9:00 a.m. CALL TO ORDER – Cindy Whaley, Commission Vice Chair • Call of the roll • Introduction of Staff • Changes to agenda • Logistics 9:05 a.m. 2019-21 OPERATING BUDGET UPDATE- Shelly Hagen, Assistant Director • This item provides the Commission with updated information regarding the 2019-21 operating budget proposal submitted to the Office of Financial Management 9:35 a.m. SUMMER OPERATIONS REPORT – Mike Sternback, Assistant Director • This item updates the Commission on events and highlights on the 2018 Summer season and field operations. 10:00 a.m. BREAK 10:15 a.m. CAPITAL PROJECTS LIST REFINEMENT- Peter Herzog, Assistant Director • This item outlines refinements to capital projects and budget figures staff has made subsequent to the Commission’s approval of its 2019- 21 capital budget submittal. 11:00 a.m. STAFF REPORTS 11:40 a.m. NASPD CONFERENCE 11:50 a.m. LUNCH 12:20 p.m. MID-YEAR COMMISSION/DIRECTOR IDENTIFIED PRIORITIES FOR 2018 UPDATE – Peter Herzog, Assistant Director 1 • This item updates the Commission on progress staff has made on 2018 performance measures included in the agency’s strategic plan and Director’s performance agreement. -

Program Accomplishments Invasive Plants

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Invasive Pacific Northwest Region Plants Program Accomplishments Dr. Tamzen Stringham and associates from University of Nevada developed state-and-transition models for the Crooked River National Grassland and trained staff on application for improved invasive plant management and prevention. Fiscal Year 2017 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission

Don Hoch Director STATE OF WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION 1111 Israel Road SW P.O. Box 42650 Olympia, Washington 98504-2650 (360) 902-8500 Washington Telecommunications Relay Service at (800) 833-6388 www.parks.wa.gov DETERMINATION OF NONSIGNIFICANCE Description of proposal: Agency Director consideration of a technical rock climbing management plan for Beacon Rock State Park pursuant to Washington Administrative Code (WAC) 352-32-085. The climbing management plan identifies measures intended to safeguard natural and cultural resources for portions of Beacon Rock State Park that are open to the public for recreational climbing and bouldering. This State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) checklist analyzes the non-project impacts associated with this proposal. Any future proposals that are associated with this plan will undergo additional review under SEPA as appropriate. Proponent: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission Location of proposal, including street address, if any: Beacon Rock State Park, 34841 State Highway 14, Skamania, Washington approximately 35 miles east of Vancouver. The majority of the climbing activities described in this plan will be located at Beacon Rock just south of State Highway 14. Lead agency: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission The lead agency for this proposal has determined that it does not have a probable significant adverse impact on the environment. An environmental impact statement (EIS) is not required under RCW 43.21C.030(2)(c). This decision was made after review of a completed environmental checklist and other information on file with the lead agency. This information is available to the public on request. There is no comment period for this DNS. -

Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Critical Habitat Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No

2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Critical Habitat Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed April 15, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Simcoe $4,000 Wenas-Cleman Mountian $1,875 McLoughlin Falls West $1,500 Grays River Watershed West Fork Conservation Area $2,000 Rendezvous Additions $1,275 Hunter Mountain $650 Chafey Mountain $590 Leland Conservation Easement $770 Wolf Fork Conservation Easement $497 Golden Doe $1,900 Allen Family Ranch Conservation Easement $36 Total $15,093 2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Farmland Preservation Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed April 15, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Wolf Creek Agricultural Conservation Easement Phase 1 $1,140 Natembea Farm Preservation $430 Hannan Farm $255 Synarep Rangeland $527 Thornton Ranch Agricultural Easement $917 Sunny Okanogan Angus Ranch $205 Upper Naneum Creek Farm $300 Teas Ranch $109 Allen Family Ranch Farmland Preservation Easement $377 VanderWerff Agricultural Conservation Easement $114 Leland Farmland Preservation Easement $241 Hoch Family Farm Agricultural Easement $505 Peyton Ranch Conservation Easement $743 Total $5,862 2021-23 Capital Budget Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program Forestland Preservation Category Ranked List LEAP Capital Document No. 2021-42 Developed April 15, 2021 (Dollars in Thousands) Project Name Amount Funded Little Skookum Inlet Forest Protection Phase 2 $321 Anderson Forestland -

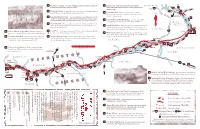

Lewis & Clark Map No K.Indd

Y a Y Y k 49 a i 43 a The Corps established a defensive position here on both the Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste k m Rock Fort Campsite LePage Park W A N A P U M k 43 49 i 43 The Corps established a defensive position here on both the 49 Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste im a Rock Fort Campsite The Corps established a defensive position here on both the LePage Park Named for the Corps' Private Jean Baptiste W A N A P U M m R. 395 a R outbound and return journeys. Interpretive signs. LePage, whose name Lewis & Clark gave to today's John Day River. R. 182 395 outbound and return journeys. Interpretive signs. LePage, whose name Lewis & Clark gave to today's John Day River. 82 182 v e r Interpretive sign. 82 182 k e R i v e r Interpretive sign. a k e R i v Interpretive sign. 12 n a k 240 PASCO S n 44 The Dalles Murals At several locations in the downtown area, large murals depict PASCO 12 S 44 The Dalles Murals At several locations in the downtown area, large murals depict 240 S Lewis & Clark's arrival and the Indian trading center at Celilo. 50 Crow Butte Park The Corps camped nearby, traveling by 60 Lewis & Clark's arrival and the Indian trading center at Celilo. 50 Crow Butte Park The Corps camped nearby, traveling by 60 horseback on the return jouney, long before dam flooding created 16-17 Oct.