APPENDIX L Avian Conservation Implementation Plans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Diasporic Choices - Locating the Lived Experiences of Afro- Crucians in the Archival and Archaeological Record

Vol. 8, No. 2, 2019 ISSN (ONLINE) 2245-294X Ayana Omilade Flewellen, UC’s President Postdoctoral Fellow, University of California, Berkeley, [email protected] African Diasporic Choices - Locating the Lived Experiences of Afro- Crucians in the Archival and Archaeological Record Abstract The year 2017 marked the centennial transfer of the Virgin Islands from Denmark to the United States. In light of this commemoration, topics related to representations of the past, and the preservation of heritage in the present -- entangled with the residuum of Danish colonialism and the lasting impact of U.S. neo-imperial rule -- are at the forefront of public dialogue on both sides of the Atlantic. Archaeological and archival research adds historical depth to these conversations, providing new insights into the lived experiences of Afro-Crucians from enslavement through post-emancipation. However, these two sources of primary historical data (i.e., material culture and documentary evidence) are not without their limitations. This article draws on Black feminist and post-colonial theoretical frameworks to interrogate the historicity of archaeological and archival records. Preliminary archaeological and archival work ongoing at the Estate Little Princess, an 18th-century former Danish sugar plantation on the island of St. Croix, provides the backdrop through which the potentiality of archaeological and documentary data are explored. Research questions centered on exploring sartorial practices of self-making engaged by Afro-Crucians from slavery through freedom are used to illuminate spaces of tension as well as productive encounters between the archaeological and archival records. Keywords: Danish West Indies, Historical Archaeology, Digital Humanities, African Diaspora, Sartorial Practices, Adornment Introduction The year 2017 marked the centennial transfer of, the now, U.S. -

Alexander Hamilton: Estate Grange and Other Sites Special Resource Study / Boundary Study St

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alexander Hamilton: Estate Grange and Other Sites Special Resource Study / Boundary Study St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands ALEXANDER HAMILTON: ESTATE GRANGE AND OTHER SITES SPECIAL RESOURCE STUDY / BOUNDARY STUDY St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands Lead Agency: National Park Service The Department of the Interior, National Park Service (NPS), has prepared the Alexander Hamilton: Estate Grange and Other Sites Special Resource Study / Boundary Study to evaluate the potential of four sites associated with Alexander Hamilton’s childhood and adolescence on St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands to be included within the national park system. As directed by Congress, this document includes a special resource study that evaluates four sites for their inclusion in the national park system as new, independent units. The boundary study portion of this document evaluates the potential of one of the sites, Estate Grange, as an addition to an existing unit of the national park system (Christiansted National Historic Site). The other three sites were not analyzed in the boundary study because they either did not possess extant resources or the resource type and associated interpretive theme is currently sufficiently represented at Christiansted National Historic Site. The boundary study evaluated several factors to determine the feasibility of adding the area to Christiansted National Historic Site, whether other options for management were available, and how the area would enhance visitor enjoyment of Christiansted National Historic Site related to park purposes. i SUMMARY INTRODUCTION significance at the national level. For cultural resources, national significance is evaluated The Department of the Interior, National by applying the National Historic Landmarks Park Service (National Park Service), has (NHL) nomination criteria contained in 36 prepared this special resource study / CFR Part 65. -

Island Journey Island Journey

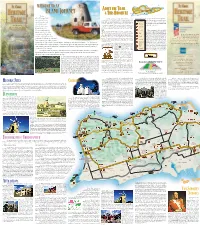

WELCOME TO AN CHRISTIANSTED About the trail ST. CROIX ISLAND JOURNEY & this brochure FREDERIKSTED The St. Croix Heritage Trail As with many memorable journeys, there is no association with each site represent attributes found there, traverses the entire real beginning or end of the trail. You may want to start such as greathouse, windmill, nature, Key to Icons 28 mile length of St. your drive at either Christiansted or Frederiksted as a or viewscape. All St. Croix roads are not portrayed, so do not consider this Croix, linking the point of reference, or you can begin at a point close to Greathouse Your Guide to the where you’re staying. If you want to take it easy, you can a detailed road map. historic seaports of History, Culture, and Nature cover the trail in segments by following particular Sugar Mill of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands Frederiksted and subroutes, such as the “East End Loop,” delineated on the Christiansted with the map. Chimney Please remember to drive on the left, fertile central plain, the The Heritage Trail will take you to three levels of sites: a remnant traffic rule bequeathed by our full-service Attractions that can be toured: Visitation Ruin Danish past. The speed limit along the mountainous Northside, Sites, like churches, with irregular hours; and Points of Trail ranges between 25 and 35 mph, We are proud that the St. Croix Church unless otherwise noted. Seat belts are Heritage Trail has been designated and the arid East End. The r e Interest, which you can view, but are not open to the tl u B one of fifty Millennium Legacy Trails by public. -

Wildlife Sanctuaries

WILDLIFE SANCTUARIES AND OTHER PROTECTED AREAS IN THE US VIRGIN ISLANDS Prior to 1975, little was known about the ecology of Photo: Sean Linehan, NOAA the more than 50 islands and Aerial view of Buck Island Reef National Monument cays dotting the perimeter of the USVI. But with the help of the Division of Fish and Wildlife’s wildlife survey, these cays have come to be known as virtual incubators of ecological activity, providing prime nesting habitat for 99% of the islands’ seabird population. As a result, all 33 territorially owned offshore cays have been Photo: Judy Pierce, DFW designated as wildlife sanctuaries to protect the beauty of these islands and the nesting habitat for Masked Booby and Chick on Cockroach Cay generations to come. Other islands, cays and coastal areas in the USVI are also recognized for their ecological importance as habitat for sea turtles, the endangered St. Croix ground lizard, elkhorn and staghorn corals, seabirds, and spawning habitat for scores of coral reef organisms. While some of these islands and cays are privately owned and threatened by development, Mangrove Lagoon Marine Reserve and Wildlife Sanctuary Capella and Buck Island off the south side of St. Thomas many are under federal government ownership and protection. 3 2 Photo: Judy Pierce, DFW ECOLOGY OF USVI PROTECTED AREAS Photo: Kevin T. Edwards Major USVI seabird nesting areas are found on 25 of the most remote cays off St. Thomas and St. John, where their eggs and offspring are less vulnerable to predators than on the major islands. Seabird communities are the most diverse and important component of this ecosystem. -

Historic Preservation Review Board Dr

COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE COMMITTEE REPORT 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20004 DRAFT TO: All Councilmembers FROM: Chairman Phil Mendelson Committee of the Whole DATE: July 13, 2021 SUBJECT: Report on PR 24-226, “Historic Preservation Review Board Dr. Alexandra Jones Confirmation Resolution of 2021” The Committee of the Whole, to which PR 24-226, the “Historic Preservation Review Board Dr. Alexandra Jones Confirmation Resolution of 2021,” was referred, reports favorably thereon and recommends approval by the Council. CONTENTS I. Background and Need ................................................................1 II. Legislative Chronology ..............................................................5 III. Position of The Executive ..........................................................6 IV. Comments of Advisory Neighborhood Commissions ...............6 V. Summary of Testimony ..............................................................6 VI. Impact on Existing Law .............................................................7 VII. Fiscal Impact ..............................................................................7 VIII. Section-By-Section Analysis .....................................................7 IX. Committee Action ......................................................................8 X. Attachments ...............................................................................8 I. BACKGROUND AND NEED On May 11, 2021, PR 24-226, the “Historic Preservation Review Board