Challenges and Opportunities in Implementing the Ecosystem Approach to Small-Scale Fisheries Management (EAFM) in Misamis Occidental, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Provincial Government of Albay and the Center for Initiatives And

Strengthening Climate Resilience Provincial Government of Albay and the SCR Center for Initiatives and Research on Climate Adaptation Case Study Summary PHILIPPINES Which of the three pillars does this project or policy intervention best illustrate? Tackling Exposure to Changing Hazards and Disaster Impacts Enhancing Adaptive Capacity Addressing Poverty, Vulnerabil- ity and their Causes In 2008, the Province of Albay in the Philippines was declared a "Global Local Government Unit (LGU) model for Climate Change Adapta- tion" by the UN-ISDR and the World Bank. The province has boldly initiated many innovative approaches to tackling disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA) in Albay and continues to integrate CCA into its current DRM structure. Albay maintains its position as the first mover in terms of climate smart DRR by imple- menting good practices to ensure zero casualty during calamities, which is why the province is now being recognized throughout the world as a local govern- ment exemplar in Climate Change Adap- tation. It has pioneered in mainstreaming “Think Global Warming. Act Local Adaptation.” CCA in the education sector by devel- oping a curriculum to teach CCA from -- Provincial Government of Albay the primary level up which will be imple- Through the leadership of Gov. Joey S. Salceda, Albay province has become the first province to mented in schools beginning the 2010 proclaim climate change adaptation as a governing policy, and the Provincial Government of Albay schoolyear. Countless information, edu- cation and communication activities have (PGA) was unanimously proclaimed as the first and pioneering prototype for local Climate Change been organized to create climate change Adaptation. -

Coastal Law Enforcement

8 Coastal law enforcement units must be formed and functional in all coastal LGUs to promote voluntary compliance with and to apprehend violators of national and local laws and regulations. This guidebook was produced by: Department of Department of the Department of Environment and Interior and Local Agriculture - Bureau of Natural Resources Government Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Local Government Units, Nongovernment Organizations, and other Assisting Organizations through the Coastal Resource Management Project, a technical assistance project supported by the United States Agency for International Development. Technical support and management is provided by: The Coastal Resource Management Project, 5/F Cebu International Finance Corporation Towers J. Luna Ave. cor. J.L. Briones St., North Reclamation Area 6000 Cebu City, Philippines Tels.: (63-32) 232-1821 to 22, 412-0487 to 89 Fax: (63-32) 232-1825 Hotline: 1-800-1888-1823 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.oneocean.org PHILIPPINE COASTAL MANAGEMENT GUIDEBOOK SERIES NO. 8: COASTAL LAW ENFORCEMENT By: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture Department of the Interior and Local Government and Coastal Resource Management Project of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources supported by the United States Agency for International Development Philippines PHILIPPINE COASTAL MANAGEMENT GUIDEBOOK SERIES NO. 8 Coastal Law Enforcement by Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture (DA-BFAR) Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) and Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP) 2001 Printed in Cebu City, Philippines Citation: Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture, and Department of the Interior and Local Government. -

Nd Drrm C Upd Date

NDRRMC UPDATE Sitrep No. 15 re: Effects of Tropical Depression “AGATON” Releasing Officer: USEC EDUARDO D. DEL ROSARIO Executive Director, NDRRMC DATE : 19 January 2014, 6:00 AM Sources: PAGASA, OCDRCs V,VII, IX, X, XI, CARAGA, DPWH, PCG, MIAA, AFP, PRC, DOH and DSWD I. SITUATION OVERVIEW: Tropical Depression "AGATON" has moved southeastward while maintaining its strength. PAGASA Track as of 2 AM, 19 January 2014 Satellite Picture at 4:32 AM., 19 January 2014 Location of Center: 166 km East of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur (as of 4:00 a.m.) Coordinates: 8.0°N 127.8°E Strength: Maximum sustained winds of 55 kph near the center Movement: Forecast to move South Southwest at 5 kph Monday morninng: 145 km Southeast of Hinatuan, Surigao del Sur Tuesday morninng: Forecast 87 km Southeast of Davao City Positions/Outlook: Wednesday morning: 190 km Southwest of Davao City or at 75 km West of General Santos City Areas Having Public Storm Warning Signal PSWS # Mindanao Signal No. 1 Surigao del Norte (30-60 kph winds may be expected in at Siargao Is. least 36 hours) Surigao del Sur Dinagat Province Agusan del Norte Agusan del Sur Davao Oriental Compostela Valley Estimated rainfall amount is from 5 - 15 mm per hour (moderate - heavy) within the 300 km diameter of the Tropical Depression Tropical Depression "AGATON" will bring moderate to occasionally heavy rains and thunderstorms over Visayas Sea travel is risky over the seaboards of Luzon and Visayas. The public and the disaster risk reduction and management councils concerned are advised to take appropriate actions II. -

Rapid Shelter Assessment After Tropical Storm Sendong in Region 10, Philippines

APID HELTER SSESSMENT AFTER R S A TROPICAL STORM SENDONG IN REGION 10, PHILIPPINES SHELTER CLUSTER REPORT FEBRUARY 2012 REACH RapidShelterAssessmentofTropicalStormSendonginPhilippines2 This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Commission. The views expressed herein should not be taken, in any way, to reflect the official opinion of the European Commission RapidShelterAssessmentofTropicalStormSendonginPhilippinesi Table of Contents Figures and Tables.......................................................................................................................................ii Acronyms...................................................................................................................................................iii Geographic Classifications...........................................................................................................................iii 1. Executive Summary...........................................................................................................................1 1.1. Context of Tropical Storm Sendong....................................................................................................1 1.2. Assessment Methodology..................................................................................................................1 1.3. Assessment Results..........................................................................................................................2 Demographic and Vulnerabilities......................................................................................................................2 -

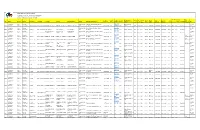

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (As of 18 April 2018)

Philippines: Marawi Armed-Conflict 3W (as of 18 April 2018) CITY OF Misamis Number of Activities by Status, Cluster & Number of Agencies EL SALVADOR Oriental 138 7,082 ALUBIJID Agencies Activities INITAO Number of CAGAYAN DE CLUSTER Ongoing Planned Completed OPOL ORO CITY (Capital) organizations NAAWAN Number of activities by Municipality/City 1-10 11-50 51-100 101-500 501-1,256 P Cash 12 27 69 10 CCCM 0 0 ILIGAN CITY 571 3 Misamis LINAMON Occidental BACOLOD Coord. 1 0 14 3 KAUSWAGAN TAGOLOAN MATUNGAO MAIGO BALOI POONA KOLAMBUGAN PANTAR TAGOLOAN II Bukidnon PIAGAPO Educ. 32 32 236 11 KAPAI Lanao del Norte PANTAO SAGUIARAN TANGCAL RAGAT MUNAI MARAWI MAGSAYSAY DITSAAN- CITY BUBONG PIAGAPO RAMAIN TUBOD FSAL 23 27 571 53 MARANTAO LALA BUADIPOSO- BAROY BUNTONG MADALUM BALINDONG SALVADOR MULONDO MAGUING TUGAYA TARAKA Health 79 20 537 KAPATAGAN 30 MADAMBA BACOLOD- Lanao TAMPARAN KALAWI SAPAD Lake POONA BAYABAO GANASSI PUALAS BINIDAYAN LUMBACA- Logistics 0 0 3 1 NUNUNGAN MASIU LUMBA-BAYABAO SULTAN NAGA DIMAPORO BAYANG UNAYAN PAGAYAWAN LUMBAYANAGUE BUMBARAN TUBARAN Multi- CALANOGAS LUMBATAN cluster 7 1 146 32 SULTAN PICONG (SULTAN GUMANDER) BUTIG DUMALONDONG WAO MAROGONG Non-Food Items 1 0 221 MALABANG 36 BALABAGAN Nutrition 82 209 519 15 KAPATAGAN Protection 61 37 1,538 37 Maguindanao Shelter 4 4 99 North Cotabato 7 WASH 177 45 1,510 32 COTABATO CITY TOTAL 640 402 6,034 The boundaries, names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Creation date: 18 April 2018 Sources: PSA -

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018

Philippine Port Authority Contracts Awarded for CY 2018 Head Office Project Contractor Amount of Project Date of NOA Date of Contract Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 27-Nov-19 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of JARZOE Builders, Inc./ DALEBO Construction and General. 328,013,357.76 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Estancia, Iloilo; Culasi, Roxas City; and Dumaguit, New Washington, Aklan Merchandise/JV Proposed Construction and Offshore Installation of Aids to Marine Navigation at Ports of Lipata, Goldridge Construction & Development Corporation / JARZOE 200,000,842.41 27-Nov-19 06-Dec-19 Culasi, Antique; San Jose de Buenavista, Antique and Sibunag, Guimaras Builders, Inc/JV Consultancy Services for the Conduct of Feasibility Studies and Formulation of Master Plans at Science & Vision for Technology, Inc./ Syconsult, INC./JV 26,046,800.00 12-Nov-19 16-Dec-19 Selected Ports Davila Port Development Project, Port of Davila, Davila, Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte RCE Global Construction, Inc. 103,511,759.47 24-Oct-19 09-Dec-19 Procurement of Security Services for PPA, Port Security Cluster - National Capital Region, Central and Northern Luzon Comprising PPA Head Office, Port Management Offices (PMOs) of NCR- Lockheed Global Security and Investigation Service, Inc. 90,258,364.20 23-Dec-19 North, NCR-South, Bataan/Aurora and Northern Luzon and Terminal Management Offices (TMO's) Ports Under their Respective Jurisdiction Rehabilitation of Existing RC Pier, Port of Baybay, Leyte A. -

REGION 10 #Coopagainstcovid19

COOPERATIVES ALL OVER THE COUNTRY GOING THE EXTRA MILE TO SERVE THEIR MEMBERS AND COMMUNITIES AMIDST COVID-19 PANDEMIC: REPORTS FROM REGION 10 #CoopAgainstCOVID19 Region 10 Cooperatives Countervail COVID-19 Challenge CAGAYAN DE ORO CITY - The challenge of facing life with CoViD-19 continues. But this emergency revealed one thing: the power of cooperation exhibited by cooperatives proved equal if not stronger than the CoVID-19 virus. Cooperatives continued to show their compassion not just to ease the burden of fear of contracting the deadly and unseen virus, but also to ease the burden of hunger and thirst, and the burden of poverty and lack of daily sustenance. In Lanao del Norte, cooperatives continued to show their support by giving a second round of assistance through the Iligan City Cooperative Development Council (ICCDC), where they distributed food packs and relief goods to micro cooperatives namely: Lambaguhon Barinaut MPC of Brgy. San Roque, BS Modla MPC, and Women Survivors Marketing Cooperative. All of these cooperatives are from Iligan City. In the Province of Misamis Oriental, the spirit of cooperativism continues to shine through amidst this pandemic. The Fresh Fruit Homemakers Consumer Cooperative in Mahayahay, Medina, Misamis Oriental extended help by distributing relief food packages to their members and community. The First Jasaan Multi-Purpose Cooperative provided food assistance and distributed grocery items to different families affected by Covid 19 in Solana, Jasaan, Misamis Oriental. Meanwhile, the Misamis Oriental PNP Employees Multi- Purpose Cooperative initiated a gift-giving program to the poor families of San Martin, Villanueva, Misamis Oriental. Finally, the Mambajao Central School Teachers and Employees Cooperative (MACESTECO) in Mambajao, Camiguin distributed rice packs and relief items to their community. -

The Impact of Remittances on Human Resource Development Decisions, Youth Employment Decisions, and Entrepreneurship in the Philippines Using CBMS Data

The impact of remittances on human resource development decisions, youth employment decisions, and entrepreneurship in the Philippines using CBMS Data Christopher James R. Cabuay Angelo King Institute for Economic and Business Studies De La Salle University I. Introduction a. Background For the past few decades, international migration has been an avenue for Filipinos to seek employment abroad. The stock of Filipino migrants has reached 10,489,628 in 2012 (Commission of Filipinos Overseas [CFO], 2014). Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) have been going to Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Qatar for employment (Philippine Overseas Employment Administration [POEA], 2014). Migration is often coupled with the sending of remittances to one’s household in the country of origin. These remittances have become a major avenue for many households to maximize income and smoothen consumption spending over time. OFW remittances has been a significant driver of the Philippine economy especially since it fuels the property market with a strong demand from medium-low-income wage earners among families with OFWs (Villegas, 2014). Remittances have grown over the past decades and have reached 18.76 USD billion in 2010 (BangkoSentralngPilipinas [BSP], 2014) and growing further to 22.97 USD billion in 2013. The largest remittances come from USA (about 9.9 USD billion), followed by Saudi Arabia (approximately 2.1 USD billion), United Kingdom (1.32 USD billion) United Arab Emirates (1.26 USD billion), Singapore, Japan, and Canada (BSP, 2014). This indicates the dependency of the Philippine economy to the remittances from overseas workers. Despite the prevalence of the phenomenon, a significant question still remains: how are remittances being used by families? Tabuga (2007) finds that remittances generally decrease the household’s budget allocated for food, but increases the budget allocated for education, medical care, housing and repairs, consumer goods, leisure, gifts, and durables. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway

EAAFP WMBD2021Small Grant Application Form Report for World Migratory Bird Day 2021 Event in East Asian-Australasian Flyway 1 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form Date of Submission: May 20, 2021 1. EVENT INFORMATION 1.1 Contact Information Full Name EnP. Grace V. Villanueva Name of the organisation Misamis University,Philippines Name(s) of the division Misamis University Community Extension Program and/or position / Director Misamis University College of Maritime Education Type of the organisation - Academe Government/NGO/Private Sector/Other Email [email protected] Postal address H.T. Feliciano Street, Aguada, Ozamiz City, Philippines Office phone numbers 088-531 loc 135 (Your) Cell number (optional) 09163514058 Fax(optional) 521-0431 Fax 2917 Website(optional) https:www.mu.edu.ph Additional contact person For. Bobby B. Alaman (optional) Date of submission May 18, 2021 1.2 Event tile: Conservation of Wildlife Migratory Bird and Wetland Areas in Misamis Occidental, Philippines through Advocacy and Capacity Development 1.3 Event Location - Where did your event take place? Name of country Philippines Name of city Ozamiz City Name of event place/venue Installation of CEPA Billboards- Barangay Migpange, Bonifacio, Misamis Occidental, Barangay Mantic, Tangub City and Poblacion, Sinacaban, Misamis Occidental, Municipalities of Plaridel and Baliangao Posting of CEPA Posters- 25 coastal barangays within Misamis Occidental. Virtual Lecture –Workshop hosted by Misamis University held at MUCEP Office, Misamis University, Ozamiz City via Zoom Celebration of WMBD 2021 Coastal Clean Up and Bird Watching – Barangay Mialen, Clarin, Misamis Occidental 2 EAAFP WMBD 2021 Small Grant Application Form 1.4 Event Type - Check the relevant categories of your event type Public awareness activity – local and/or national / Field Trip (e.g. -

NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries

MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO.: X- NORTHERN MINDANAO Directory of Mines and Quarries - CY 2020 Other Plant Locations Status Mine Site Mine Mine Site E- Head Office Head Office Head Office E- Head Office Mine Site Mailing Type of Permit Date Date of Area municipality, Non- Telephon Site Fax mail barangay Year Region Mineral Province Municipality Commodity Contractor Operator Managing Official Position Head Office Mailing Address Telephone No. Fax No. mail Address Website (hectares) province Producing TIN Address e No. No. Address Permit Number Approved Expiration Producing donjieanim 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Poblacion, Sapang Dalaga, Misamis as@yahoo Dioyo, Sapang 191-223- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Sapang Dalaga Sand and Gravel ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ANIMAS, EMILOU M. ager Occidental 9654955493 N/A .com N/A Dalaga N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-07-19 11/10/2019 10/10/2020 1.00 N/A N/A Producing 205 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man South Western, Calamba, Misamis ljcyap7@g 432-503- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. YAP, LORNA T. ager Occidental 9466875752 N/A mail.com N/A Sulipat, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-18-19 04/02/2020 03/02/2021 1.9524 N/A N/A Producing 363 maconsuel 10-Northern Non- Misamis ROGELIO, MARIA ROGELIO, MA. ROGELIO, MA. Proprietor/Man Northern Poblacion, Calamba, Misamis orogelio@ 325-550- 2020 Mindanao Metallic Occidental Calamba Sand and Gravel CONSUELO A. CONSUELO A. CONSUELO ager Occidental 9464997271 N/A gmail.com N/A Solinog, Calamba N/A N/A N/A CSAG RP-03-20 24/06/2020 23/06/2021 1.094 N/A N/A Producing 921 noel_pagu 10-Northern Non- Misamis Proprietor/Man Southern Poblacion, Plaridel, Misamis e@yahoo.