Heredity in the Dog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Crufts 2019 Order Form

LABOKLIN @ CRUFTS 2019 TH TH 7 – 10 March 10% Discount* on all DNA tests submitted at Crufts Dear Breeder / Dog Owner, We are pleased to inform you that LABOKLIN will be at Crufts 2019 and we look forward to seeing you there. Our stand is located in Hall 3 opposite the restaurant, it is stand number 3-7a. 10% Discount on all DNA tests submitted at Crufts ! and this includes our new Breed Specific DNA Bundles. You can submit a sample at Crufts in the following ways: 1) Bring your dog to our stand 3-7a, we will take a DNA sample for your genetic test, all you need to do is complete this order form and pay the fees. Or, 2) If you don't want to wait in the queue, you can prepare your sample in advance and bring it together with this order form with you to our stand, you can order a free DNA testing kit on our website www.laboklin.co.uk. We will send you a testing kit which also contains instructions on how to take DNA sample. Prepare your sample up to a week before your planned visit, just hand the sample to us. 3) If you prefer to use blood for your test, ask your vet to collect 0.5-1 ml of whole blood in EDTA blood tube, bring it together with the completed order form to the show, just hand it to us. Please note we will only accept Cash, Cheques or Postal Orders at the show. If you wish to pay by card, you can complete the card payment section. -

Dog Breeds Pack 1 Professional Vector Graphics Page 1

DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 1 Affenpinscher Afghan Hound Aidi Airedale Terrier Akbash Akita Inu Alano Español Alaskan Klee Kai Alaskan Malamute Alpine Dachsbracke American American American American Akita American Bulldog Cocker Spaniel Eskimo Dog Foxhound American American Mastiff American Pit American American Hairless Terrier Bull Terrier Staffordshire Terrier Water Spaniel Anatolian Anglo-Français Appenzeller Shepherd Dog de Petite Vénerie Sennenhund Ariege Pointer Ariegeois COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 1 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 2 Armant Armenian Artois Hound Australian Australian Kelpie Gampr dog Cattle Dog Australian Australian Australian Stumpy Australian Terrier Austrian Black Shepherd Silky Terrier Tail Cattle Dog and Tan Hound Austrian Pinscher Azawakh Bakharwal Dog Barbet Basenji Basque Basset Artésien Basset Bleu Basset Fauve Basset Griffon Shepherd Dog Normand de Gascogne de Bretagne Vendeen, Petit Basset Griffon Bavarian Mountain Vendéen, Grand Basset Hound Hound Beagle Beagle-Harrier COPYRIGHT (c) 2013 FOLIEN.DS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. WWW.VECTORART.AT DOG BREEDS PACK 2 PROFESSIONAL VECTOR GRAPHICS PAGE 3 Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bearded Collie Beauceron Bedlington Terrier (Tervuren) Dog (Groenendael) Belgian Shepherd Belgian Shepherd Bergamasco Dog (Laekenois) Dog (Malinois) Shepherd Berger Blanc Suisse Berger Picard Bernese Mountain Black and Berner Laufhund Dog Bichon Frisé Billy Tan Coonhound Black and Tan Black Norwegian -

Full Competitor List

Competitor List Argentina Entries: 2 Height Handler Dog Breed 300 Fernando Estevez Costas Arya Mini Poodle 600 Jorge Esteban Ramos Trice Border Collie Salinas Australia Entries: 6 Height Handler Dog Breed 400 Reserve Dog Casper Dutch Smoushond 500 Maria Thiry Tebbie Border Collie 500 Maria Thiry Beat Pumi 600 Emily Abrahams Loki Border Collie 600 Reserve Dog Ferno Border Collie 600 Gillian Self Showtime Border Collie Austria Entries: 12 Height Handler Dog Breed 300 Helgar Blum Tim Parson Russell Ter 300 Markus Fuska Cerry Lee Shetland Sheepdog 300 Markus Fuska Nala Crossbreed 300 Petra Reichetzer Pixxel Shetland Sheepdog 400 Gabriele Breitenseher Aileen Shetland Sheepdog 400 Gregor Lindtner Asrael Shetland Sheepdog 400 Daniela Lubei Ebby Shetland Sheepdog 500 Petra Reichetzer Paisley Border Collie 500 Hermann Schauhuber Haily Border Collie 600 Michaela Melcher Treat Border Collie 600 Sonja Mladek Flynn Border Collie 600 Sonja Mladek Trigger Border Collie Belgium Entries: 17 Height Handler Dog Breed 300 Dorothy Capeta Mauricio Ben Jack Russell Terrier 300 Ann Herreman Lance Shetland Sheepdog 300 Brechje Pots Dille Jack Russell Terrier 300 Kristel Van Den Eynde Mini Jack Russell Terrier 400 Ann Herreman Qiell Shetland Sheepdog 400 Anneleen Holluyn Hjatho Mini Australian Shep 400 Anneleen Holluyn Ippy Mini Australian Shep 26-Apr-19 19:05 World Agility Open 2019 Page 1 of 14 500 Franky De Witte Laser Border Collie 500 Franky De Witte Idol Border Collie 500 Erik Denecker Tara Border Collie 500 Philippe Dubois Jessy Border Collie 600 Kevin Baert -

Annual Report 2017 REPORT ANNUAL 2017 Annual Report 4 Table of Contents

2017 Annual report 2017 ANNUAL SECRETARIAT GENERAL DE LA FCI Place Albert 1er, 13 REPORT B-6530 THUIN • BELGIUM Tel. : +32 71 59 12 38 Fax : +32 71 59 22 29 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 www.fci.be • www.dogdotcom.be www.facebook.com/FederationCynologiqueInternationale 2017 Annual report 4 Table of contents Table of contents I. Message from the President 5 II. Mission Statement 6 III. The General Committee 8 IV. FCI staff 10 V. Executive Director’s report 11 VI. Outstanding Conformation Dogs of the Year 14 VII. Our commissions 17 VIII. Financial report 45 IX. Figures 48 X. 2018 events 60 XI. List of members 70 XII. List of clubs with an FCI contract 79 Fédération Cynologique Internationale Chapter I Message from the President 5 Message from the President The time has come for a groups and activities, and to support already-existing youth new report about FCI ac- groups in FCI member National Canine Organisations. tivities. It is always a stim- Following the publication of the Guide: How to Create a ulating experience to go National Youth Canine Organisation, the FCI Youth has pro- through our achievements vided support during the past year to several National Canine when writing this yearly Organisations that were interested in initiating youth groups outline. Having a retro- and national youth activities. spective look at the huge During the 2017 General Assembly, the FCI General work carried out and short- Committee appointed a new FCI Youth Coordination: Mr listing the priority tasks for Augusto Benedicto Santos. FCI Youth welcomed Blai Llobet the next term is one of the from Spain, and Jimmie Wu from China, as the two new most rewarding and chal- group members who are now on board. -

HERDING BREEDS ELIGIBLE to COMPETE in ASCA STOCKDOG TRIALS Ref: the Atlas of Dog Breeds of the World - Bonnie Wilcox, DVM & Chris Walkowic

ASCA STOCKDOG PROGRAM RULES – JUNE 2014 APPENDIX 6: HERDING BREEDS ELIGIBLE TO COMPETE IN ASCA STOCKDOG TRIALS Ref: The Atlas of Dog Breeds of the World - Bonnie Wilcox, DVM & Chris Walkowic Breed Country of Origin Breed Country of Origin Australian Cattle Dog Australia Greater Swiss Mountain Dog Switzerland Australian Kelpie Australia Hairy Mouth Heeler USA Australian Shepherd USA Hovawart Germany Belgian Laekenois Belgium Iceland Dog Iceland Belgian Malinois Belgium Kerry Blue Terrier Ireland Belgian Sheep Dog Lancashire Heeler Great Britain (Groenendael) Belgium Lapinporokoira Belgian Tervuren Belgium (Lapponian Herder) Finland Bouviers Des Flandres Belgium Malinois Belgian Bergamasco Italy McNab USA Bernese Mtn Dog Switzerland Miniature Australian Shepherd USA Beauceron France Mudi Hungary Briard France North American Shepherd USA Bearded Collie Great Britain Norwegian Buhund Norway Border Collie Great Britain Old English Sheep Dog Great Britain Blue Lacy USA Picardy Shepherd France Catahoula Leopard Dog USA Polish Owczarek Nizinny Poland Canaan Dog Israel Puli Hungary Cao de Serra de Aires Pumi Hungary (Portuguese Sheep Dog) Portugal Pyrenean Shepherd France Croatian Sheep Dog Croatia Rottweiler Germany Cataian Sheep Dog Spain Samoyed Scandinavia Collie Great Britain Schapendoes Corgi (Dutch Sheepdog) Netherlands Cardigan Welsh Great Britain Shetland Sheep Dog Great Britain Pembroke Welsh Great Britain Soft Coated Wheaten Terrier Ireland Dutch Shepherd: Netherlands Spanish Water Dog Spain English Shepherd USA Swedish Lapphund Sweden Entlebucher Mountain Dog Switzerland Tibetan Terrier China Finnish Lapphund Finland Vasgotaspets Sweden German Shepherd Dog Germany White Shepherd USA German Coolie/Koolie Australia 74 . -

Commencing Implementation of a Genetic Evaluation System for Livestock Working Dogs by C

Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation system for livestock working dogs by C. M. Wade, D. van Rooy, E. R. Arnott, J. B. Early and P. D. McGreevy June 2021 Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation system for livestock working dogs by C. M. Wade, D. van Rooy, E. R. Arnott, J. B. Early and P. D. McGreevy June 2021 i © 2021 AgriFutures Australia All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-76053-135-5 ISSN 1440-6845 Commencing implementation of a genetic evaluation for livestock working dogs Publication No. 20-117 Project No: PRJ-010413 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, AgriFutures Australia, the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, AgriFutures Australia, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Cattle Dogs (Except Swiss Cattle Dogs)

FEDERATION CYNOLOGIQUE INTERNATIONALE (AISBL) Place Albert 1er, 13, B – 6530 Thuin (Belgique), tel : +32.71.59.12.38, fax : +32.71.59.22.29, email : [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________________________ NOMENCLATORUL RASELOR CANINE FCI DENUMIREA RASELOR ESTE REDATĂ ÎN LIMBA ŢĂRII DE ORIGINE. VARIETĂŢILE DE RASĂ SI DENUMIRILE TARILOR DE ORIGINE SAU PATRONAJ SUNT REDATE ÎN LIMBA ENGLEZĂ CONŢINE SPECIFICAŢIILE CU PRIVIRE LA ACORDAREA TITLULUI C.A.C.I.B. DE CĂTRE F.C.I. SI ACORDAREA TITLULUI C.A.C. DE CĂTRE A.CH.R. VALABIL DE LA 01.03.2008 ( ) = Numai pentru ţările care au solicitat ( ) = Numai pentru ţările nordice (Suedia, Norvegia, Finlanda) GRUPA / GROUP 1 Câini de turmă și Câini de cireadă (cu excepția câinilor de cireadă Elvețieni) Sheepdogs and Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle Dogs) Section 1: Câini de turmă / Sheepdogs Section 2: Câini de cireadă ( cu excepția câinilor de cireadă Elvețieni) / Cattle Dogs (except Swiss Cattle dogs) CACIB CAC WORKING TRIAL SECTION 1 : SHEEPDOGS 1. AUSTRALIA Australian Kelpie (293) 2. BELGIUM Chien de Berger Belge (15) (Belgian Shepherd Dog) a) Groenendael b) Laekenois c) Malinois d) Tervueren Schipperke (83) 3. CROATIA Hrvatski Ovcar (277) (Croatian Sheepdog) 4. FRANCE Berger de Beauce (Beauceron) (44) Berger de Brie (Briard) (113) Chien de Berger des Pyrénées à poil long (141) (Long-haired Pyrenean Sheepdog) Berger Picard (176) (Picardy Sheepdog) Berger des Pyrénées à face rase (138) (Pyrenean Sheepdog - smooth faced) 5. GERMANY Deutscher Schaferhund (166) German Shepherd Dog a) Double coat b) Long and harsh outer coat 6. GREAT BRITAIN Bearded Collie (271) Old English Sheepdog (Bobtail) (16) Border Collie (297) Collie Rough (156) Collie Smooth (296) Shetland Sheepdog (88) Welsh Corgi Cardigan (38) Welsh Corgi Pembroke (39) 7. -

Les Hypertypes Dans L'espèce Canine

ÉCOLE NATIONALE VÉTÉRINAIRE D’ALFORT Année 2019 LES HYPERTYPES DANS L’ESPÈCE CANINE : ASPECTS CYNOTECHNIQUES, SOCIÉTAUX ET LÉGISLATIFS THÈSE Pour le DOCTORAT VÉTÉRINAIRE Présentée et soutenue publiquement devant LA FACULTÉ DE MÉDECINE DE CRÉTEIL Le 14 mars 2019 Par Marion HUE Née le 16 août 1992 à Saint-Germain-en-Laye (Yvelines) JURY Président : Pr. Professeur à la Faculté de Médecine de CRÉTEIL Membres Directeur : Professeur BOSSÉ Philippe Responsable Unité pédagogique de zootechnie, économie rurale Assesseur : Docteure CHEVALLIER Lucie Unité pédagogique de physiologie, éthologie, génétique REMERCIEMENTS Au Professeur de la faculté de médecine de Créteil, en tant que président du jury, pour m’avoir fait l’honneur d’accepter la présidence de cette thèse et de vous être déplacé à L’École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort. Avec mon plus profond respect. À Monsieur le Professeur Philipe BOSSÉ, Responsable de l’unité pédagogique de zootechnie, économie rurale de l’École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort d’avoir accepté d’être mon directeur de thèse et pour avoir corrigé mon travail au fur et à mesure de ma rédaction. À Madame le Docteure Lucie CHEVALLIER, Maître de conférences, membre de l’unité pédagogique de physiologie, éthologie, génétique de l’École Nationale vétérinaire d’Alfort d’avoir accepté d’être mon assesseur. Merci de votre bienveillance et de votre motivation. Avec mon plus profond respect. À ma maman, Merci d’avoir toujours été là pour mes études, mes déménagements, mes mo- ments de stress et mes plus grands bonheurs. Merci pour tes conseils, qui m’ont toujours servi. Tu sais toujours trouver les mots justes. -

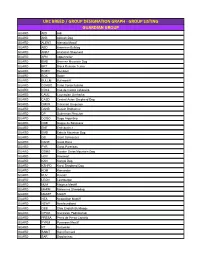

Ukc Breed / Group Designation Graph

UKC BREED / GROUP DESIGNATION GRAPH - GROUP LISTING GUARDIAN GROUP GUARD AIDI Aidi GUARD AKB Akbash Dog GUARD ALENT Alentejo Mastiff GUARD ABD American Bulldog GUARD ANAT Anatolian Shepherd GUARD APN Appenzeller GUARD BMD Bernese Mountain Dog GUARD BRT Black Russian Terrier GUARD BOER Boerboel GUARD BOX Boxer GUARD BULLM Bullmastiff GUARD CORSO Cane Corso Italiano GUARD CDCL Cao de Castro Laboreiro GUARD CAUC Caucasian Ovcharka GUARD CASD Central Asian Shepherd Dog GUARD CMUR Cimarron Uruguayo GUARD DANB Danish Broholmer GUARD DP Doberman Pinscher GUARD DOGO Dogo Argentino GUARD DDB Dogue de Bordeaux GUARD ENT Entlebucher GUARD EMD Estrela Mountain Dog GUARD GS Giant Schnauzer GUARD DANE Great Dane GUARD PYR Great Pyrenees GUARD GSMD Greater Swiss Mountain Dog GUARD HOV Hovawart GUARD KAN Kangal Dog GUARD KSHPD Karst Shepherd Dog GUARD KOM Komondor GUARD KUV Kuvasz GUARD LEON Leonberger GUARD MJM Majorca Mastiff GUARD MARM Maremma Sheepdog GUARD MASTF Mastiff GUARD NEA Neapolitan Mastiff GUARD NEWF Newfoundland GUARD OEB Olde English Bulldogge GUARD OPOD Owczarek Podhalanski GUARD PRESA Perro de Presa Canario GUARD PYRM Pyrenean Mastiff GUARD RT Rottweiler GUARD SAINT Saint Bernard GUARD SAR Sarplaninac GUARD SC Slovak Cuvac GUARD SMAST Spanish Mastiff GUARD SSCH Standard Schnauzer GUARD TM Tibetan Mastiff GUARD TJAK Tornjak GUARD TOSA Tosa Ken SCENTHOUND GROUP SCENT AD Alpine Dachsbracke SCENT B&T American Black & Tan Coonhound SCENT AF American Foxhound SCENT ALH American Leopard Hound SCENT AFVP Anglo-Francais de Petite Venerie SCENT -

Characterization of Native Nordic Farm Animal Breeds - State of Knowledge, 8.12.2015

Characterization of native Nordic Farm Animal breeds - State of knowledge, 8.12.2015 The aim of this document is to provide a list of references outlining the current extent of characterization, both phenotypic and genetic, of native Nordic farm animal breeds. Google scholar was used to search for any scientific publications, including student theses and reports, on Nordic breeds of the main farm animal species: cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, chicken, dog and horse. The table below lists the breed names that were used as search keys. When present in the table, both the English as well as the original breed name were employed. No searches in Finnish or Icelandic language were conducted. Breed English name of breed Species Country Danske Landhøns Danish Landrace chicken chicken Denmark Finnish Landrace chicken chicken Finland Icelandic landrace chicken chicken Iceland Jærhøns Jær hen chicken Norway Skånsk blommehöna chicken Sweden Åsbohöna Åsbos chicken Sweden Ölandshöna Ölands chicken Sweden Gotlandshöna chicken Sweden Kindahöna chicken Sweden Hedemorahöna chicken Sweden Orusthöna chicken Sweden Bohuslän-dals svarthöna, gammalsvensk dvärghöna, öländsk dvärghöna chicken Sweden Sortbroget Dansk Malkerace, anno 1965 Danish Black pied Dairy cattle cattle Denmark Agersøkvæg cattle Denmark Rød Dansk Malkerace, anno 1970 cattle Denmark Jysk kvæg Jutland cattle cattle Denmark Malkekorthorn Danish Shorthorn cattle cattle Denmark Eastern Finn cattle cattle Finland Western Finn cattle cattle Finland Northern Finn cattle cattle Finland Icelandic cattle -

Instructions Regarding Compulsory Measuring of Breeds at Championship Shows Organized by the Swedish Kennel Club and Associated Clubs

January 2020 Instructions regarding compulsory measuring of breeds at Championship Shows organized by the Swedish Kennel Club and associated clubs The measuring of the height at withers should be undertaken with the dog standing on flat and firm ground. The measuring should be done at the highest point of the shoulder blades (top of shoulder). The result of the measuring will be noted by the ring steward, both on the dog’s individual critique sheet and the list of results. For Dachshunds the measuring of chest circumference should be done around the deepest part of chest. For Poodles (Caniche), Dachshunds, Xoloitzcuintle (Mexican Hairless Dog) and Perro sin pelo del Péru (Peruvian Hairless Dog) and Deutscher Spitz/Klein- Mittel- & Grosspitz (German Spitz/ GrossMedium size Spitz & Miniature Spitz) the procedure should be undertaken before the start of the judging. Only dogs which have not been “finally measured” should be measured. A dog should always be judged together with the breed variety corresponding with the result of the measuring even if it has been entered in a class for another variety. The result of the measuring will be noted by the ring steward, both on the dog’s individual critique sheet and the list of results; for Dachshunds the result should be accounted in centimetres (of chest circumference), for Poodles only the breed variety (medium size, miniature or toy) is noted. The size limits for each variety – regarding height at withers and chest circumference – are stated in the FCI breed standard. For the other breeds listed below the measurement result should be noted in centimetres in the dog’s individual critique and the list of results, by the ring steward.