Afghan Languages (Dari and Pashto) As a Source of Unity Rather Than Division Johnathan Krause Western Carolina University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

Tajiki Some Useful Phrases in Tajiki Five Reasons Why You Should Ассалому Алейкум

TAJIKI SOME USEFUL PHRASES IN TAJIKI FIVE REASONS WHY YOU SHOULD ассалому алейкум. LEARN MORE ABOUT TAJIKIS AND [ˌasːaˈlɔmu aˈlɛɪkum] /asah-lomu ah-lay-koom./ THEIR LANGUAGE Hello! 1. Tajiki is spoken as a first or second language by over 8 million people worldwide, but the Hоми шумо? highest population of speakers is located in [ˈnɔmi ʃuˈmɔ] Tajikistan, with significant populations in other /No-mee shoo-moh?/ Central Eurasian countries such as Afghanistan, What is your name? Uzbekistan, and Russia. Номи ман… 2. Tajiki is a member of the Western Iranian branch [ˈnɔmi man …] of the Indo-Iranian languages, and shares many structural similarities to other Persian languages /No-mee man.../ such as Dari and Farsi. My name is… 3. Few people in America can speak or use the Tajiki Шумо чи xeл? Нағз, рахмат. version of Persian. Given the different script and [ʃuˈmɔ ʧi χɛl naʁz ɾaχˈmat] dialectal differences, simply knowing Farsi is not /shoo-moh-chee-khel? Naghz, rah-mat./ enough to fully understand Tajiki. Those who How are you? I’m fine, thank you. study Tajiki can find careers in a variety of fields including translation and interpreting, consulting, Aз вохуриамон шод ҳастам. and foreign service and intelligence. NGOs [az vɔχuˈɾiamɔn ʃɔd χaˈstam] and other enterprises that deal with Tajikistan /Az vo-khu-ri-amon shod has-tam./ desperately need specialists who speak Tajiki. Nice to meet you. 4. The Pamir Mountains which have an elevation Лутфан. / Рахмат. of 23,000 feet are known locally as the “Roof of [lutˈfan] / [ɾaχˈmat] the World”. Mountains make up more than 90 /Loot-fan./ /Rah-mat./ percent of Tajikistan’s territory. -

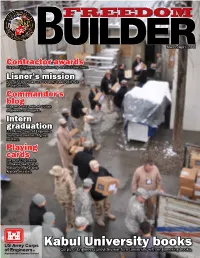

Kabul University Books Corps of Engineers Provides War-Torn University with Engineering Books

March/April 2011 Contractor awards Corps of Engineers recognizes top construction firms. Lisner’s mission N.D. Air Force man serves Army leadership role in Afghanistan. Commander's blog Magness touts role of civilian engineers to bloggers. Intern graduation U.S. Army Corps of Engineers trains and mentors Afghan soldiers. Playing cards Corps of Engineers, Embassy team up to explain the deal with Afghan artifacts. Kabul University books Corps of Engineers provides war-torn university with engineering books. C h Tajikistan in Uz a bekis tan District Commander Col. Thomas Magness AED-North District Command Sergeant Major hshan dak Chief Master Sgt. Forest Lisner Ba Chief of Public Affairs ar J. D. Hardesty uz kh Kund Ta K Layout & Design ash Joseph A. Marek m jan Balkh wz ir Staff Writer Ja Paul Giblin lan Staff Writer gh LaDonna Davis n Ba n ta angan r ta is am e ris n S jsh u e Pan N ar m ul un The Freedom Builder is the field magazine of the Far P K k yab ri n Kapisa n Afghanistan Engineer District, U.S. Army Corps of r a wa L a S ar aghm Engineers; and is an unofficial publication authorized u Bamyan P Kabul by AR 360-1. It is produced monthly for electronic ul ories - r distribution by the Public Affairs Office, U.S. Army T ab St rha K ga Corps of Engineers, Afghanistan Engineer District. It is an produced in the Afghanistan theater of operations. N Views and opinions expressed in The Freedom ardak r Builder are not necessarily those of the Department of n W a dghis g the Army or the U.S. -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-Standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik

ARTICLE Development of a Gold-standard Pashto Dataset and a Segmentation App Yan Han and Marek Rychlik ABSTRACT The article aims to introduce a gold-standard Pashto dataset and a segmentation app. The Pashto dataset consists of 300 line images and corresponding Pashto text from three selected books. A line image is simply an image consisting of one text line from a scanned page. To our knowledge, this is one of the first open access datasets which directly maps line images to their corresponding text in the Pashto language. We also introduce the development of a segmentation app using textbox expanding algorithms, a different approach to OCR segmentation. The authors discuss the steps to build a Pashto dataset and develop our unique approach to segmentation. The article starts with the nature of the Pashto alphabet and its unique diacritics which require special considerations for segmentation. Needs for datasets and a few available Pashto datasets are reviewed. Criteria of selection of data sources are discussed and three books were selected by our language specialist from the Afghan Digital Repository. The authors review previous segmentation methods and introduce a new approach to segmentation for Pashto content. The segmentation app and results are discussed to show readers how to adjust variables for different books. Our unique segmentation approach uses an expanding textbox method which performs very well given the nature of the Pashto scripts. The app can also be used for Persian and other languages using the Arabic writing system. The dataset can be used for OCR training, OCR testing, and machine learning applications related to content in Pashto. -

Judeo-Persian Literature Chapter Author(S): Vera Basch Moreen Book

Princeton University Press Chapter Title: Judeo-Persian Literature Chapter Author(s): Vera Basch Moreen Book Title: A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations Book Subtitle: From the Origins to the Present Day Book Editor(s): Abdelwahab Meddeb, Benjamin Stora Published by: Princeton University Press. (2013) Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt3fgz64.80 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Princeton University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to A History of Jewish-Muslim Relations This content downloaded from 89.176.194.108 on Sun, 12 Apr 2020 13:51:06 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Judeo- Persian Literature Vera Basch Moreen Jews have lived in Iran for almost three millennia and became profoundly acculturated to many aspects of Iranian life. This phenomenon is particu- larly manifest in the literary sphere, defi ned here broadly to include belles lettres, as well as nonbelletristic (i.e., historical, philosophical, and polemi- cal) writings. Although Iranian Jews spoke Vera Basch Moreen many local dialects and some peculiar Jewish dialects, such as the hybrid lo- Vera Basch Moreen is an independent Torah[i] (Heb. + Pers. -

Features of Identity of the Population of Afghanistan

SHS Web of Conferences 50, 01236 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185001236 CILDIAH-2018 Features of Identity of the Population of Afghanistan Olga Ladygina* Department of History and International Relations, Russian-Tajik Slavonic University, M.Tursunzoda str., 30, Dushanbe, 734025, Tajikistan Abstract. The issues of identity of the population of Afghanistan, which is viewed as a complex self- developing system with the dissipative structure are studied in the article. The factors influencing the development of the structure of the identity of the society of Afghanistan, including natural and geographical environment, social structure of the society, political factors, as well as the features of the historically established economic and cultural types of the population of Afghanistan, i.e. the Pashtuns and Tajiks are described. The author of the article compares the mental characteristics of the bearers of agriculture and the culture of pastoralists and nomads on the basis of description of cultivated values and behavior stereotypes. The study of the factors that influence the formation of the identity of the Afghan society made it possible to justify the argument about the prevalence of local forms of identity within the Afghan society. It is shown that the prevalence of local forms of identity results in the political instability. Besides, it constrains the process of development of national identity and articulation of national idea which may ensure the society consolidation. The relevance of such studies lies in the fact that today one of the threats of Afghanistan is the separatist sentiments coming from the ethnic political elites, which, in turn, negatively affects the entire political situation in the region and can lead to the implementation of centrifugal scenarios in the Central Asian states. -

INSPIRE the Monthly Employee Newsletter

19th Issue INSPIRE The Monthly Employee Newsletter November 2020 Employee of The Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer Staff Birthdays New Employees Introduction Reflections Birthday Wishes Kardan University wishes a happy birthday to all of our employees who celebrate their birthdays in November. Wahidullah Ibrahimkhail Ahmad Zaki Ludin November 2 November 4 Sarbajeet Mukherjee Faisal Hashimi November 6 November 6 Alauddin Qurishi Jahanzeb Ahmadzai November 8 November 11 Ahmad Khetab Roohullah Hassanyar November 22 November 13 Employee of the Month Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb Economics Department Lecturer We are pleased to announce Ms. Sajida Mohammad Tayyeb as our Employee for November 2020. Ms. Tayyeb is an inspiring, committed, and dedicated employee of Kardan University. Ms. Sajida has been immensely cooperative with her students, who are on the verge of graduation to complete their final project. She is handling the online sessions of the department with diligence. Additionally, she has been deeply involved in developing the Departments and the Faculty of Economics' Strategic Plan for the past month. She is also working with the DRD to conduct the upcoming National Conference on SDGs. She is a very dedicated employee, kind teacher, and energetic colleague. The whole department is happy to work by her side We congratulate her on this achievement and wish her the best of luck in her future endeavors. New Employees Introduction Mr. Abdullah Salihy Graphic Designer Mr. Abdullah Salihy joined Kardan University as a Graphic Designer in the Office of Communications. Mr. Salihy holds a bachelor's degree in Fine Arts with a specialization in Graphic Design from Kabul University. -

The Socio Linguistic Situation and Language Policy of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan: the Case of the Tajik Language*

THE SOCIO LINGUISTIC SITUATION AND LANGUAGE POLICY OF THE AUTONOMOUS REGION OF MOUNTAINOUS BADAKHSHAN: THE CASE OF THE TAJIK LANGUAGE* Leila Dodykhudoeva Institute Of Linguistics, Russian Academy Of Sciences The paper deals with the problem of closely related languages of the Eastern and Western Iranian origin that coexist in a close neighbourhood in a rather compact area of one region of Republic Tajikistan. These are a group of "minor" Pamir languages and state language of Tajikistan - Tajik. The population of the Autonomous Region of Mountainous Badakhshan speaks different Pamir languages. They are: Shughni, Rushani, Khufi, Bartangi, Roshorvi, Sariqoli; Yazghulami; Wakhi; Ishkashimi. These languages have no script and written tradition and are used only as spoken languages in the region. The status of these languages and many other local linguemes is still discussed in Iranology. Nearly all Pamir languages to a certain extent can be called "endangered". Some of these languages, like Yazghulami, Roshorvi, Ishkashimi are included into "The Red Book " (UNESCO 1995) as "endangered". Some of them are extinct. Information on other idioms up to now is not available. These languages live in close cooperation and interaction with the state language of Tajikistan - Tajik. Almost all population of Badakhshan is multilingual or bilingual. The second language is official language of the state - Tajik. This language is used in Badakhshan as the language of education, press, media, and culture. This is the reason why this paper is focused on the status of Tajik language in Republic Tajikistan and particularly in Badakhshan. The Tajik literary language (its oral and written forms) has a long history and rich written traditions. -

Can Afghan Universities Recover from War

NEWSFOCUS Afghan elite. Graduates at Ameri- can University of Afghanistan in Kabul celebrate, but their career plans are uncertain. satisfy the country’s desperate need for technical talent. “After 3 decades of war, Afghanistan has lost one-and-a-half gener- ations of experts in all fi elds,” says Timor Saffary, the head of AUAF’s department of sci- ence and mathematics. “The intellectual elites either left the country or have passed away, leaving a huge vacuum.” Saffary earned Ph.D.s in both mathematics and physics and worked as a postdoctoral researcher in Germany before joining AUAF in 2009, and the 39-year-old native of Kabul hopes to be a part of the gen- eration who fi lls that vacuum. With the help of the United on August 13, 2012 States and other countries, Afghan academics are begin- ning to pick up the pieces. But a deadline looms: Inter- national military forces are preparing to leave the country HIGHER EDUCATION by the end of 2014, and it’s anybody’s guess what will happen after they are gone. “Many of the highest qualifi ed and talented academ- www.sciencemag.org Can Afghan Universities Recover ics are looking nervously at the 2014 with- drawal,” says Michael Petterson, a geologist From War, Taliban, and Neglect? at the University of Leicester in the United Kingdom who leads fi eld research and train- The demand for technical talent and outside funding is helping colleges get back on ing workshops in the region. “And who can their feet. But higher education is still not a priority blame them?” Downloaded from KABUL—Except for the armed guards in ating from high school in Kabul, Fazel left Afghan ivy body armor at the entrance, on the roof, and Afghanistan and eventually earned a Ph.D. -

The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: a Case Study of Afghanistan

The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: A Case Study of Afghanistan Students in their classroom in Zhari district, Khandahar province, Afghanistan. Many of the school’s September 2021 buildings were destroyed in airstrikes, leaving classrooms exposed. © 2019 Stefanie Glinski The Impact of Explosive Weapons on Education: A Case Study of Afghanistan Summary Between January 2018 and June 2021, the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA) identified over 200 reported attacks on schools, school students and personnel, and higher education in Afghanistan that involved explosive weapons. These attacks injured or killed hundreds of students and educators and damaged or destroyed dozens of schools and universities. In the first six months of 2021, more attacks on schools using explosive weapons were reported than in the first half of any of the previous three years. Explosive weapons were used in an increasing proportion of all attacks on education since 2018, with improvised explo- sive devices most prevalent among these attacks. Attacks with explosive weapons also caused school closures, including when non-state armed groups used explosive weapons to target girls’ education. Recommendations • Access to education should be a priority in Afghanistan, and schools and universities, as well as their students and educators, should be protected from attack. • State armed forces and non-state armed groups should avoid using explosive weapons with wide-area effects in populated areas, including near schools or universities, and along routes to or from them. • When possible, concerned parties should make every effort to collect and share disaggregat- ed data on attacks on education involving explosive weapons, so that the impact of these attacks can be better understood, and prevention and response measures can be devel- oped.