Pipeline Or Pipe Dream: the Otp Ential of Peace Pipelines As a Solution to Fragmentation and Energy Insecurity in the European Union Afton J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Energy Triangle of Cyprus-Greece-Israel: Casting a Net for Turkey?

THE NEW ENERGY TRIANGLE OF CYPRUS-GREECE-ISRAEL: CASTING A NET FOR TURKEY? A long-running speculation over massive natural gas reserves in the tumultuous area of the Southeastern Mediterranean became a reality in December 2011 and the discovery's timing along with other grave and interwoven events in the region came to create a veritable tinderbox. The classic “Rubik's cube” puzzle here is in perfect sync with the realities on the ground and how this “New Energy Triangle” (NET) of newfound and traditional allies' actions (Cyprus, Greece and Israel) towards Turkey will shape and inevitably affect the new balance of power in this crucial part of the world. George Stavris* *George Stavris is a visiting researcher at Dundee University's Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy working on the geostrategic repercussions in the region of the “New Energy Alliance” (NET) of Cyprus, Greece and Israel. 87 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 2 GEORGE STAVRIS long-running speculation over massive natural gas reserves in the tumultuous area of the Southeastern Mediterranean and in Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) became a reality in A December 2011 when official reports of the research and scoping were released. Nearby, Israel has already confirmed its own reserves right next to Cyprus’ EEZ. However the location of Cypriot reserves with all the intricacies of the intractable “Cyprus Problem” and the discovery’s timing along with other grave and interwoven events in the region came to create a veritable tinderbox. A rare combination of the above factors and ensuing complications have created not just a storm in the area but almost, indisputably, the rare occasion of a “Perfect Storm” in international politics with turbulence reaching far beyond the shores of the Mediterranean “Lake”. -

W O R K I N G P a P E R Natural Gas Import and Export

W ORKING P APER Working Paper No26 July 2019 NATURAL GAS IMPORT AND EXPORT ROUTES IN SOUTH-EAST EUROPE AND TURKEY Gina Cohen Lecturer & Consultant on Natural Gas ΙΕΝΕ Working Paper No26 NATURAL GAS IMPORT AND EXPORT ROUTES IN SOUTH-EAST EUROPE AND TURKEY Author Gina Cohen, Lecturer & Consultant on Natural Gas Institute of Energy for SE Europe (IENE) 3, Alexandrou Soutsou, 106 71 Athens, Greece tel: 0030 210 3628457, 3640278 fax: 0030 210 3646144 web: www.iene.gr, e-mail: [email protected] Copyright ©2019, Institute of Energy for SE Europe All rights reserved. No part of this study may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the Institute of Energy for South East Europe. Please note that this publication is subject to specific restrictions that limit its use and distribution. [2] ACRONYMS AERS - Energy Agency of the Republic of Serbia AIIB - Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank BCM - Billion cubic meters BOTAS - Boru Hatlari Ile Petroleum Tasima Anonim Sirketi (Petroleum Pipeline Corporation) BRUA - Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria BRUSKA- Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Slovakia-Austria EBRD - European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EITI - Exctractive Industries Transparency Initiative EPDK - Enerji Piyasasi Duzenleme Kurumu (Energy Market Regulatory Authority) EU - European Union FGSZ - Foldgazszallito Zrt. (Hungarian Gas Transmission System Operator) FSRU – Floating Storage and Regasification unit GWh - Gigawatt hour HAG - Hungaria-Austria-Gasleitung (Hungary-Austria Interconnector) -

The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations

September 2017 FEUTURE Online Paper No. 5 The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU-Turkey Relations Nona Mikhelidze, IAI Nicolò Sartori, IAI Oktay F. Tanrisever, METU Theodoros Tsakiris, ELIAMEP Online Paper No. 5 “The Moscow-Ankara Energy Axis and the Future of EU -Turkey Relations ” ABSTRACT The Turkey-Russia-EU energy triangle is a relationship of interdependence and strategic compromise. However, Russian support for secessionism and erosion of state autonomy in the Caucasus and Eurasia has proven difficult to reconcile for western European states despite their energy dependence. Yet, Turkey has enjoyed an enhanced bilateral relationship with Russia, augmenting its position and relevance in a strategic energy relationship with the EU. The relationship between Ankara and Moscow is principally based on energy security and domestic business interests, and has largely remained stable in times of regional turmoil. This paper analyses the dynamics of Ankara-Moscow cooperation in order to understand which of the three scenarios in EU –Turkey relations – conflict, cooperation or convergence – could be expected to develop bearing in mind that the partnership between Turkey and Russia has become unpredictable. The intimacy of Turkish-Russia energy relations and EU-Russian regional antagonism makes transactional cooperation on energy demand the most likely of future scenarios. A scenario in which both Brussels and Ankara will try to coordinate their relations with Russia through a positive agenda, in order to exploit the interdependence emerging within the “triangle”. ÖZET Türkiye Rusya ve AB arasındaki enerji üçgeni bir karşılıklı bağımlılık ve stratejik uzlaşma ilişkisidir. Ancak, her ne kadar Rusya’ya enerji bağımlılıkları olsa da, Batı Avrupalı devletler için Rusya’nın Kafkasya ve Avrasyadaki ayrılıkçılığa ve devlet özerkliğinin erozyonuna verdiği desteğin kabullenilmesinin zor olduğu ortaya çıkmıştır. -

Delivering the Energy Transition Through a Strategic Focus on Gas in the East Med Mathios Rigas, Energean Group CEO IP Week London, 25Th February 2020

Delivering the Energy Transition Through a Strategic Focus on Gas in the East Med Mathios Rigas, Energean Group CEO IP Week London, 25th February 2020 Το σχέδιο ανάπτυξης του κοιτάσματος υδρογονανθράκων στο Δυτικό Κατάκολο Δρ. Κωνσταντίνος Νικολάου, Τεχνικός Σύμβουλος Energean Δημοτικό Συμβούλιο Πύργου, 14 Νοεμβρίου 2019 1 Key questions 1. Is there a role for independent E&P players in today’s market? 2. What is the role of the East Med in delivering the energy transition? 2 1 Energean at a glance Creating the leading independent, gas-focused, sustainable E&P company in the Eastern Mediterranean 820 MMboe ~130 kboed 80% FTSE 250 2P reserves and Production gas-weighted The Largest 2C resources by 2022* portfolio independent E&P ESG & HSE ESG action Focused 1st E&P to commit A rating MSCI to net zero by 2050 *Edison E&P reserve estimates as of 31.10.2018, excludes UK, Norway and Algeria. 3 *Energean Israel reserve estimates as of 30.06.2019 CPR. Energean reserve estimates are pending finalisation of 2019 CPR. 2 *2022 production excludes UK, Norway and Algeria. Taking Action on Environmental Issues Through Focus on Gas Leaders in ESG Carbon Intensity Reduction Plan 80 80% gas-weighted portfolio Energean today 70 First E&P company to commit 60 to net zero by 2050 50 40 Targeting 70% reduction in carbon Energean intensity 2020-22 + Edison 30 E&P Energean + Edison Executive pay linked to ESG goals 20 E&P + from 2020 Israel 10 Committed to transparency and 0 adherence to the UN SDG’s 2019 2021 2022 Carbon intensity scope 1 & 2 (kgCO2/boe) 4 3 -

A Shaping Factor for Regional Stability in the Eastern Mediterranean?

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT STUDY Energy: a shaping factor for regional stability in the Eastern Mediterranean? ABSTRACT Since 2010 the Eastern Mediterranean region has become a hotspot of international energy discussions due to a series of gas discoveries in the offshore of Israel, Cyprus and Egypt. To exploit this gas potential, a number of export options have progressively been discussed, alongside new regional cooperation scenarios. Hopes have also been expressed about the potential role of new gas discoveries in strengthening not only the regional energy cooperation, but also the overall regional economic and political stability. However, initial expectations largely cooled down over time, particularly due to delays in investment decision in Israel and the downward revision of gas resources in Cyprus. These developments even raised scepticism about the idea of the Eastern Mediterranean becoming a sizeable gas- exporting region. But initial expectations were revived in 2015, after the discovery of the large Zohr gas field in offshore Egypt. Considering its large size, this discovery has reshaped the regional gas outlook, and has also raised new regional cooperation prospects. However, multiple lines of conflict in the region continue to make future Eastern Mediterranean gas activities a major geopolitical issue. This study seeks to provide a comprehensive analysis of all these developments, with the ultimate aim of assessing the realistic implications of regional gas discoveries for both Eastern Mediterranean countries and the EU. EP/EXPO/B/AFET/2016/03 EN June 2017 - PE578.044 © European Union, 2017 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs. -

Gas Infrastructure Map of the Mediterranean Region

Empowering Mediterranean regulators for a common energy future. Working Group on Gas (GAS WG) GAS INFRASTRUCTURE MAP OF THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION MED17-24GA -5.4.2 FINAL REPORT Luogo, data MEDREG is co-funded by the European Union MEDREG – Association of Mediterranean Energy Regulators Corso di Porta Vittoria 27, 20122 Milan, Italy - Tel + 39 02 655 65 537 - Fax +39 02 655 65 562 [email protected] – www.medreg-regulators.org Ref: MED17-24GA -5.4.2 Gas Infrastructure Map of the Mediterranean region Table of content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Work’s methodology description .................................................................................................. 6 3. Analysis of the Results ................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 TPA regimes in a nutshell ...................................................................................................... 8 3.2 A growing trend: LNG and FSRUs .......................................................................................... 8 3.3 Benefits and impacts of the investments .............................................................................. 9 3.4 Implementation barriers ...................................................................................................... 9 3.5 Key performance indicators ............................................................................................... -

Policy Brief

EUROPEAN COUNCIL ON FOREIGN BRIEF POLICY RELATIONS ecfr.eu PIPELINES AND PIPEDREAMS HOW THE EU CAN SUPPORT A REGIONAL GAS HUB IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN Tareq Baconi There has been a great deal of excitement over the past few years around newly-discovered gas reserves in the eastern SUMMARY Mediterranean, and rightly so. With confirmed reserves • Large natural gas discoveries in the eastern reaching close to 100 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas, and the Mediterranean have raised hopes that the region possibility of more discoveries to come, the Levantine Deep could serve EU energy needs, helping it to fulfil its Marine Basin has the potential to offer two things of value to goals of energy diversification, security, and resilience. the European Union: energy security, and an improvement in regional cooperation between Middle Eastern countries. • But there are commercial and political hurdles in the way. Cyprusʼs reserves are too small to be The diversification of Europe’s gas supply has long been a commercially viable and Israel needs a critical mass priority for the European Union. With gas wars taking place of buyers to begin full-scale production. Regional between Russia and EU member states in 2006 and 2009, and cooperation – either bilaterally or with Egypt – is a major escalation of diplomatic tension following Russia’s the only way the two countries will be able to export. annexation of Crimea in 2014, efforts to address this issue have accelerated in recent years.1 The prospect of reducing the EU’s • Egypt is the only country in the region that could dependency on Russian gas by securing supplies from within export gas to Europe independently because Europe’s geographical vicinity could help the EU build energy of the size of its reserves and its existing export resilience – a stated goal of its Energy Union strategy. -

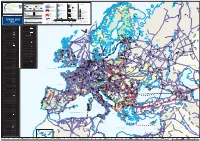

TYNDP 2017 FID Status (Final Investment Decision) White Sea PCI Status (Project of Common Interest) Submission

SHTOKMAN SNØHVIT Pechora Sea ASKELADD MELKØYA KEYS ALBATROSS Hammerfest Salekhard Cross-border points / intra-country or intra balancing zone points Transport by pipeline LNG Import Terminals Storage facilities Compressor stations Barents KILDIN N Acquifer Sea 1ACross-border interconnection point Cross-border interconnection point Pipeline diameters : LNG Terminals’ entry point within Europe within Europe Diameter < 600 mm intro transmission system Salt cavity - cavern or export point to non-EU country or export point to non-EU country Operational Under construction or Planned Diameter 600 - 900 mm Depleted (Gas) eld on shore / oshore MURMAN Diameter > 900mm Other type Unknown Cross-border interconnection point Cross-border third country (import) with third country (import) Under construction or Planned Pomorskiy Project categories : Project categories : Project categories : Project categories : Strait Intra-country or Murmansk Third country cross-border FID projects FID projects FID projects intra balancing zone points interconnection point FID projects Non-FID, advanced projects Non-FID, advanced projects Non-FID, advanced projects REYKJAVIK Non-FID, advanced projects Non-FID, non-advanced projects Non-FID, non-advanced projects Non-FID, non-advanced projects Gas Reserve areas Countries Non-FID, non-advanced projects ENTSOG Member Countries ICELAND Project is part of 2nd PCI list : Project is part of 2nd PCI list : Project is part of 2nd PCI list : Project is part of 2nd PCI list : Drilling platform ENTSOG Associated Partner P ENTSOG -

Energy Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Impact of the Cyprus Issue and Relevance for the Eu Energy Security

CENTRE INTERNATIONAL DE FORMATION EUROPEENNE SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT INSTITUT EUROPEEN · EUROPEAN INSTITUTE ENERGY DISCOVERIES IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN: IMPACT OF THE CYPRUS ISSUE AND RELEVANCE FOR THE EU ENERGY SECURITY BY Beliz Küçükosman A thesis submitted for the Joint Master degree in Global Economic Governance & Public Affairs (GEGPA) Academic year 2019 – 2020 July 2020 Supervisor: Giulio Venneri Reviewer: Lorenzo Liso PLAGIARISM STATEMENT I certify that this thesis is my own work, based on my personal study and/or research and that I have acknowledged all material and sources used in its preparation. I further certify that I have not copied or used any ideas or formulations from any book, article or thesis, in printed or electronic form, without specifically mentioning their origin, and that the complete citations are indicated in quotation marks. I also certify that this assignment/report has not previously been submitted for assessment in any other unit, except where specific permission has been granted from all unit coordinators involved, and that I have not copied in part or whole or otherwise plagiarized the work of other students and/or persons. In accordance with the law, failure to comply with these regulations makes me liable to prosecution by the disciplinary commission and the courts of the French Republic for university plagiarism. 1 Table of Contents Glossary of Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ -

Energy Security in the Eastern Mediterranean

Prontera / Ruszel: Energy Security in the Eastern Mediterranean Energy Security in the Eastern Mediterranean Andrea Prontera and Mariusz Ruszel Dr. Prontera is assistant professor of international relations in the Department of Political Science, Communication and International Relations, University of Macerata, Italy. His latest book is The New Politics of Energy Security in the European Union and Beyond: States, Markets, Institutions (Routledge, 2017). Dr. Ruszel is assistant professor in the Department of Economics, Rzeszow University of Technology, Poland. he geopolitical significance of the means considering energy trade as a tool Mediterranean Sea region is the for achieving foreign-policy and security result of three factors: its location objectives.3 However, the geopolitics of at the junction of Europe, Asia natural gas is particularly complex. In Tand Africa; its significant international sea contrast to oil, natural gas has physical routes and straits — Gibraltar, Bosphorus, characteristics that make transportation Dardanelles, Suez Canal — and its poten- expensive, whether through pipeline or in tial as a source of oil and natural gas. Re- liquefied form (LNG). This constitutes a cent gas discoveries in the Eastern Medi- significant fraction of the total delivered terranean have only reaffirmed this poten- cost of the gas trade and is an important tial. They have resulted in a set of signifi- component of the sector’s political econ- cant geoeconomic decisions concerning omy.4 Normally, the infrastructure for gas the development of flows and exchanges transportation requires huge investments, a in the form of traded gas. It is emphasized long-term perspective and political stabil- in the literature that the geoeconomy may ity. -

Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2020 Edition

Insight Report Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2020 edition May 2020 World Economic Forum 91‑93 route de la Capite CH‑1223 Cologny/Geneva Switzerland Tel.: +41 (0)22 869 1212 Fax: +41 (0)22 786 2744 Email: [email protected] www.weforum.org © 2020 World Economic Forum. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any the views of the World Economic Forum, the members of the project’s advisory committee or the means, including photocopying and recording, or Members and Partners of the World Economic Forum. by any information storage and retrieval system. Contents Preface 4 Executive summary 6 1. Introduction 9 2. Framework 11 3. Overall results 15 4. Sub‑index and dimension trends 19 4.1 System performance 19 4.1.1 Economic development and growth 21 4.1.2 Environmental sustainability 25 4.1.3 Energy access and security 25 4.2 Transition readiness 27 5. Imperatives for the energy transition 29 5.1 Regulations and political commitment 29 5.2 Capital and investment 32 5.3 Innovation and infrastructure 35 5.4 Economic structure 37 5.5 Consumer engagement 39 6. Conclusion 42 Appendices 44 1. Annual Energy Transition Index score differences, 2015‑2020 44 2. Methodology 45 3. Regional classification 46 Contributors 47 Endnotes 48 Fostering Effective Energy Transition 2020 edition 3 Preface The World Economic Forum Platform for Shaping the Future of Energy and Materials, with the support of its global community of diverse stakeholders, serves to promote collaborative action and exchange best practices to foster an effective energy transition. -

Israel's Contradictory Gas Export Policy. the Promotion of A

NO. 43 NOVEMBER 2019 Introduction Israel’s Contradictory Gas Export Policy The Promotion of a Transcontinental Pipeline Contradicts the Declared Goal of Regional Cooperation Stefan Wolfrum In order to market its gas reserves, Israel has until now relied on exports to Egypt and Jordan. Through regional networking in the energy sector – for example, within the framework of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), which was founded at the beginning of 2019 – the Israeli government hopes to improve its political relations in the region. At the same time, Israel is investing hope in the building of the EastMed gas pipeline. Its construction would create a direct export link to Europe, but it would thereby also undermine energy cooperation with its Arab neighbours. The European Union (EU) should promote regional energy cooperation, as this could promote part- nerships in other areas. Accordingly, the EU should not support the construction of the EastMed pipeline. Israel is estimated to have between 800 bil- awarded all exploitation rights for the lion to 1 trillion cubic metres (m³) of natu- Tamar, Leviathan, Karish, and Tanin gas ral gas. Its own consumption amounts to fields to the American-Israeli consortium around 10 billion m³ per year; in 2017 this Noble Energy/Delek Drilling without a call corresponded to around 35 per cent of total for tenders, since they had discovered the energy consumption. However, the exploi- gas deposits. This was supposed to acceler- tation of the gas fields for the export of ate the development of the gas fields. In this gas surplus has not progressed far.