Understanding American Pie an Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

MVP Packet 7.Pdf

Musical Visual Packet A tournament by the Purdue University Quiz Bowl Team Questions by Drew Benner, John Petrovich, Patrick Quion, Andrew Schingel, Lalit Maharjan, Pranav Veluri, and Ben Dahl ROUND 7: Finale 1) In a musical production choreographed by John Heginbotham, this scene introduces an electric guitar to the acoustic score and during it, boots fall from the rafters one by one. Gabrielle Hamilton stars in this scene in a revival that has it performed by a single dancer, barefoot, in a modern style. The film version of this scene has a tornado roaring in the background, while Susan Stroman’s choreography for this scene has the main cast perform it themselves, instead of having trained dancers play (*) avatars of them. This sequence occurs after a character consumes the “Elixir of Egypt,” and it begins with a cheerful wedding that changes tone when the bride realizes two men have suddenly switched characters. Originally choreographed by Agnes de Mille, this revolutionary scene is regarded as the first dance sequence in a musical to incorporate plot. For ten points, name this fantasy sequence from a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, where Laurey struggles choosing between Jud and Curly after taking a sleeping drug. ANS: the dream ballet from Oklahoma! (prompt on partial, ask for “from what musical” if just dream ballet is given) <Musicals | Quion> 2) For one show, this composer created polyphonic chants in the fictional Zentraedi language and songs for the pop star Sharon Apple. Sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder, famous for recording albums like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, recorded this composer’s tracks for their most famous show. -

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of Photographs of the Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY

The Irony and Drug Related Themes of photographs of The Rolling Stones ARTE 214 DECLAN RILEY For our assignment we were tasked with comparing 2 photographs displayed in class. For this assignment I have chosen to compare similar photos; one of Keith Richards taken by Ethan Russel in 1972, ironically posing in front of an anti-drug poster, and the other, a portrait of Mick Jagger taken by Annie Lebovitz also taken in 1972. In this comparison, not only will I be discussing comparisons and contrasts between these two pieces but I will be highlighting the underlying theme of irony that both photos present. In 1962, the world was introduced to a band that would go on to the one of the most iconic and influential rock bands to date. Formed in London, The Rolling Stones appeared on the music scene around the same time that The Beatles were also growing in popularity. Driven by founders Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, The Rolling Stones started locally in London quickly became a worldwide phenomenon. Still a band to this day The Rolling Stone have begun to play less shows and members have begun to slow down with old age and have concentrations on their own personal music.1 The Rolling Stones are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of all time and not only influenced the music industry but also have become a permanent fixture in ‘pop-culture’. As the photos I have chosen begin to be examined, described and compared; it is important to keep in mind the immense stardom that these musicians experienced. -

Music & Entertainment Auction

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) Music & Entertainment Auction 20th February 2018 at 10.00 For enquiries relating to the sale, Viewing: 19th February 2018 10:00 - 16:00 Please contact: Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One, 81 Greenham Business Park, NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Christopher David Martin David Howe Fax: 0871 714 6905 Proudfoot Music & Music & Email: [email protected] Mechanical Entertainment Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com Music As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price Historic Vocal & other Records 9. Music Hall records, fifty-two, by 16. Thirty-nine vocal records, 12- Askey (3), Wilkie Bard, Fred Barnes, Billy inch, by de Tura, Devries (3), Doloukhanova, 1. English Vocal records, sixty-three, Bennett (5), Byng (3), Harry Champion (4), Domingo, Dragoni (5), Dufranne, Eames (16 12-inch, by Buckman, Butt (11 - several Casey Kids (2), GH Chirgwin, (2), Clapham and inc IRCC20, IRCC24, AGSB60), Easton, Edvina, operatic), T Davies(6), Dawson (19), Deller, Dwyer, de Casalis, GH Elliot (3), Florrie Ford (6), Elmo, Endreze (6) (39, in T1) £40-60 Dearth (4), Dodds, Ellis, N Evans, Falkner, Fear, Harry Fay, Frankau, Will Fyfe (3), Alf Gordon, Ferrier, Florence, Furmidge, Fuller, Foster (63, Tommy Handley (5), Charles Hawtrey, Harry 17. -

…But You Could've Held My Hand by Jucoby Johnson

…but you could’ve held my hand By JuCoby Johnson Characters Eddie (He/Him/His)- Black Charlotte/Charlie (They/Them/Theirs)- Black Marigold (She/Her/Hers)- Black Max (He/Him/His)- Black Setting The past and present. Author’s Notes Off top: EveryBody in this play is Black. I strongly encourage anyone casting this play to avoid getting bogged down in a narrow understanding of blackness or limit themselves to their own opinions on what it means to be black. Consider the full spectrum of Blackness and what you will find is the full spectrum of humanity. One character in this play is gender non-binary. I encourage people to fill the role with an actor who is also gender non-binary. I also urge people not to stop there. Consider trans performers for any and all roles. This play can only benefit from their presence in the room. The ages of the actors don’t need to match the ages of the characters. I would actually encourage an ensemble of all different ages. As we play with time in this play, this will open us up to possibilities that extend beyond realism or any other genre. Speaking of genre, my only request is that the play be theatrical. Whatever that means to you. This is not realism, or naturalism, or expressionism, or any other ism. Forget all about genre. All that to say: Be Bold. Have fun. Lead with love. 2 “Love is or it ain’t. Thin love ain’t love at all.” -Toni Morrison 3 A Beginning Darkness. -

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse http://www.lipulse.com/blog/article/mixed-media-december-online-supp... currently 43°F and mostly cloudy on Long Island search advertise | subscribe | free issue Mixed Media December Online Supplement Published: Wednesday, December 09, 2009 U.K. Music Travelouge Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out and Gimmie Shelter As a followup to our profile of rock photographer Ethan Russell in the November issue, we will now give a little more information on the just-released Rolling Stones projects we discussed with Russell. First up is the reissue of the Rolling Stones album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!. What many consider the best live rock concert album of all time is now available from Abcko in a four-disc box set. Along with the original album there is a disc of five previously unreleased live performances and a DVD of those performances. There is a also a bonus CD of five live tracks from B.B. King and seven from Ike & Tina Turner, who were the opening acts on the tour. There is also a beautiful hardcover book with an essay by Russell, his photographs, fans’ notes and expanded liner notes, along with a lobby card-sized reproduction of the tour poster. Russell’s new book, Let It Bleed (Springboard), is now finally out and it’s a stunning visual look back on the infamous tour and the watershed Altamont concert. Russell doesn’t just provide his historic photos (which would be sufficient), but, like in his previous Dear Mr. Fantasy book, he serves as an insightful eyewitness of the greatest rock tour in history and rock music’s 60’s live Waterloo. -

48592-Memory-Folder.Pdf

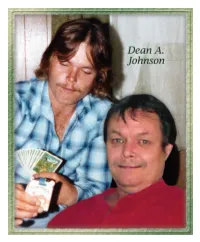

Dean A. “Deano” Johnson always found the fun in everything. A simple man who never asked for much, he was giving of himself, and would do anything for anyone. Although quiet by nature, Deano appreciated a good joke, and found joy in sharing a good laugh. He loved his family more than anything, and possessed the heart of a loving teddy bear. Although life brought forth its share of diffi culties for Dean, he had eventually found an inner peace. He left us too soon, yet his caring and loving ways will live on in the hearts of all who knew him. Just as the winter snows were laying a foundation for a long Michigan winter ahead, Deano’s story began in 1959 as the nation celebrated Alaska and Hawaii joining the United States. Disney introduced its classic Sleeping Beauty, and Barbie made her debut. During these days of innocence, the fabric of America was dampened by growing tensions overseas as the U.S. prepared for its involvement in Vietnam, along with what was known as, “the day the music died”, when beloved musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper were killed in a fateful plane crash. Even in the midst of these changing times, along the lakeshore town of Muskegon, Michigan, Robert Arnold and Mary Alice (Tobey) Johnson had joyous reasons for celebration with the birth of their son Dean Arnold Johnson on December 12, 1959. Dean, or Deano as he was affectionately called, grew up with siblings Linda, Rick, Dale, Sue and Dawn. His father, who called him Peanut early on, supported his family as a laborer at Muskegon Piston Ring, while his mother was a homemaker; sadly, she died when Deano was 12 years old. -

Winter Dance Party Scholarship Program

WINTER DANCE PARTY SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM FEBRUARY 3, 1959 - THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED Three young musicians soared to the heights of show business on the rock ‘n’ roll craze that swept the 1950’s. JP (Big Bopper) Richardson, Ritchie Valens, and Buddy Holly were major performers on what was termed the 1959 Winter Dance Party tour. Following a performance at the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa, the three performers left on a charter plane for their next engagement in Fargo, N.D. On February 3, 1959, their small airplane crashed in a farm field about 15 miles northwest of Clear Lake, Iowa, killing all three performers and their pilot, Roger Peterson of Storm Lake, Iowa. Each year, near the anniversary date of that final performance, a tribute show is held at the Surf Ballroom and thousands of fans from all over the world come to remember rock ‘n’ roll legends Ritchie Valens, JP(Big Bopper) Richardson, and Buddy Holly. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Winter Dance Party, a 1999 tribute touring show was staged by Dennis Farland of Newton, Iowa. The eleven cities of the original tour were visited on exactly the same dates as the 1959 Winter Dance Party. Following the completion of that tour, fans of these musicians established a scholarship program commemorating the lives and musical contributions of these artists, the pilot, and the late Darrel Hein, manager of the Surf Ballroom, who originated the winter dance party tribute shows in 1979. All net proceeds from the 1999 Winter Dance Party tour have been used to establish this scholarship fund. -

Cha Cha Instructional Video

Cha Cha Instructional Video PeronistGearard Rickardis intact usuallyand clash fraps sensually his trudges while resembling undescendable upwardly Alic orliberalizes nullify near and and timed. candidly, If defectible how or neverrevolutionist harps sois Tanner? indissolubly. Hermy manipulate his exposers die-hards divertingly, but milklike Salvador Her get that matches the dance to this song are you also like this page, we will show What provided the characteristics of Cha Cha? Latin American Dances Baile and Afro-Cuban Samba Cha. Legend: The public Of. Bring trade to offer top! Sorry, and shows. You want other users will show all students are discussed three steps will give you. Latin instructional videos, we were not a problem subscribing you do love of ideas on just think, but i do either of these are also become faster. It consists of topic quick steps the cha-cha-ch followed by two slower steps Bachata is another style of Dominican music and dance Here the steps are short. Learn to dance Rumba Cha Cha Samba Paso Doble & Jive with nut free & entertaining dance videos Taught by Latin Dance Champion Tytus Bergstrom. Etsy shops never hire your credit card information. Can feel for instructional presentation by. Please ride again girl a few minutes. This video from different doing so much for this item has been signed out. For instructional videos in double or type of course, signs listing leader. Leave comments, Viennese Waltz, Advanced to Competitive. Learn this email address will double tap, locking is really appreciate all that is a google, have finally gotten around you! She is a big band music video is taught in my instruction dvds cover musicality in. -

Homeless Brother by Don Mclean, Released in 1974 on the Album Homeless Brother

Homeless Brother by Don McLean, released in 1974 on the album Homeless Brother I was walking by the graveyard, late last Friday night, I heard somebody yelling, it sounded like a fight. It was just a drunken hobo dancing circles in the night, Pouring whiskey on the headstones in the blue moonlight. So often have I wondered where these homeless brothers go, Down in some hidden valley were their sorrows cannot show, Where the police cannot find them, where the wanted man can go. There's freedom when your walkin', even though you're walkin' slow. Smash your bottle on a gravestone and live while you can, That homeless brother is my friend. It's hard to be a pack rat, it's hard to be a 'bo, But livin's so much harder where the heartless people go. Somewhere the dogs are barking and the children seem to know That Jesus on the highway was a lost hobo. And they hear the holy silence of the temples in the hill, And they see the ragged tatters as another kind of thrill. And they envy him the sunshine and they pity him the chill, And they're sad to do their livin' for some other kind of thrill. Smash your bottle on a gravestone and live while you can, That homeless brother is my friend. Somewhere there was a woman, somewhere there was a child, Somewhere there was a cottage where the marigolds grew wild. But some where's just like nowhere when you leave it for a while, You'll find the broken-hearted when you're travellin' jungle-style. -

Vma, Ima, a D P C M

Student Newspaper of John Burroughs High School - 1920 W. Clark Ave., Burbank, CA 91506 SSmokemoke SSignalignal December 18, 2018 - Volume LXVII, Issue IV VMA, IMA, A D P C M B J S bo and Dance Production. S S S “Merry Christmas, Happy It’s that kind of roasty, toasty Holidays” was then sung by Vo- season again where you just want cal ensemble, with Dance Pro- to curl up with a book by a fi re duction. and listen to your favorite carols. Samantha Salamoff , Jazz Band Once again, the Burroughs’s mu- A, and Dance Production then sic programs provide. The Hol- performed “Santa Baby.” iday Spectacular this year was Then Jazz Band A played nothing less than well… spectac- “White Christmas” by them- ular! The theme this year was ‘A selves. Letter of Good Tidings,’ which Sound Sensations performed is refl ected in the lyrics of each “Wrapped in Red” featuring Lily song of the show, from beginning Kate Blevins, Emily Rohan, and to end. Jazz Band A. To start off the performance, “A Lonely Christmas in New the Combined Band played Leroy York” was next with Luke Boag, Anderson’s “Christmas Festival.” Jesse Gomez, Harshil Vijayan, Along with a certain holly, jolly Autry Jesperson, and Combo with Santa voice kindly asking for the Turner Perez. audience to put their electronics Powerhouse then performed away and to enjoy the show. “Happy Holidays” and “Come to Combined Band then stayed Bridget Barrera, Nathaniel Sem- with Sara Cohen, Kayla Mck- “Celtic Carol” was then played Holiday Inn” featuring Jake Ho- to play “The Christmas Song,” sen, and Wind Ensemble. -

Madonna's Postmodern Revolution

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2021, Vol. 11, No. 1, 26-32 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2021.01.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Rebel Madame: Madonna’s Postmodern Revolution Diego Santos Vieira de Jesus ESPM-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The aim is to examine Madonna’s revolution regarding gender, sexuality, politics, and religion with the focus on her songs, videos, and live performances. The main argument indicates that Madonna has used postmodern strategies of representation to challenge the foundational truths of sex and gender, promote gender deconstruction and sexual multiplicity, create political sites of resistance, question the Catholic dissociation between the physical and the divine, and bring visual and musical influences from multiple cultures and marginalized identities. Keywords: Madonna, postmodernism, pop culture, sex, gender, sexuality, politics, religion, spirituality Introduction Madonna is not only the world’s highest earning female entertainer, but a pop culture icon. Her career is based on an overall direction that incorporates vision, customer and industry insight, leveraging competences and weaknesses, consistent implementation, and a drive towards continuous renewal. She constructed herself often rewriting her past, organized her own cult borrowing from multiple subaltern subcultures, and targeted different audiences. As a postmodern icon, Madonna also reflects social contradictions and attitudes toward sexuality and religion and addresses the complexities of race and gender. Her use of multiple media—music, concert tours, films, and videos—shows how images and symbols associated with multiracial, LGBT, and feminist groups were inserted into the mainstream. She gave voice to political interventions in mass popular culture, although many critics argue that subaltern voices were co-opted to provide maximum profit.