Pythagoras' Theorem Information Sheet Finding the Length of the Hypotenuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euler's Square Root Laws for Negative Numbers

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Transforming Instruction in Undergraduate Complex Numbers Mathematics via Primary Historical Sources (TRIUMPHS) Winter 2020 Euler's Square Root Laws for Negative Numbers Dave Ruch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/triumphs_complex Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Euler’sSquare Root Laws for Negative Numbers David Ruch December 17, 2019 1 Introduction We learn in elementary algebra that the square root product law pa pb = pab (1) · is valid for any positive real numbers a, b. For example, p2 p3 = p6. An important question · for the study of complex variables is this: will this product law be valid when a and b are complex numbers? The great Leonard Euler discussed some aspects of this question in his 1770 book Elements of Algebra, which was written as a textbook [Euler, 1770]. However, some of his statements drew criticism [Martinez, 2007], as we shall see in the next section. 2 Euler’sIntroduction to Imaginary Numbers In the following passage with excerpts from Sections 139—148of Chapter XIII, entitled Of Impossible or Imaginary Quantities, Euler meant the quantity a to be a positive number. 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111 The squares of numbers, negative as well as positive, are always positive. ...To extract the root of a negative number, a great diffi culty arises; since there is no assignable number, the square of which would be a negative quantity. Suppose, for example, that we wished to extract the root of 4; we here require such as number as, when multiplied by itself, would produce 4; now, this number is neither +2 nor 2, because the square both of 2 and of 2 is +4, and not 4. -

The Geometry of René Descartes

BOOK FIRST The Geometry of René Descartes BOOK I PROBLEMS THE CONSTRUCTION OF WHICH REQUIRES ONLY STRAIGHT LINES AND CIRCLES ANY problem in geometry can easily be reduced to such terms that a knowledge of the lengths of certain straight lines is sufficient for its construction.1 Just as arithmetic consists of only four or five operations, namely, addition, subtraction, multiplication, division and the extraction of roots, which may be considered a kind of division, so in geometry, to find required lines it is merely necessary to add or subtract ther lines; or else, taking one line which I shall call unity in order to relate it as closely as possible to numbers,2 and which can in general be chosen arbitrarily, and having given two other lines, to find a fourth line which shall be to one of the given lines as the other is to unity (which is the same as multiplication) ; or, again, to find a fourth line which is to one of the given lines as unity is to the other (which is equivalent to division) ; or, finally, to find one, two, or several mean proportionals between unity and some other line (which is the same as extracting the square root, cube root, etc., of the given line.3 And I shall not hesitate to introduce these arithmetical terms into geometry, for the sake of greater clearness. For example, let AB be taken as unity, and let it be required to multiply BD by BC. I have only to join the points A and C, and draw DE parallel to CA ; then BE is the product of BD and BC. -

A Quartically Convergent Square Root Algorithm: an Exercise in Forensic Paleo-Mathematics

A Quartically Convergent Square Root Algorithm: An Exercise in Forensic Paleo-Mathematics David H Bailey, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, USA DHB’s website: http://crd.lbl.gov/~dhbailey! Collaborator: Jonathan M. Borwein, University of Newcastle, Australia 1 A quartically convergent algorithm for Pi: Jon and Peter Borwein’s first “big” result In 1985, Jonathan and Peter Borwein published a “quartically convergent” algorithm for π. “Quartically convergent” means that each iteration approximately quadruples the number of correct digits (provided all iterations are performed with full precision): Set a0 = 6 - sqrt[2], and y0 = sqrt[2] - 1. Then iterate: 1 (1 y4)1/4 y = − − k k+1 1+(1 y4)1/4 − k a = a (1 + y )4 22k+3y (1 + y + y2 ) k+1 k k+1 − k+1 k+1 k+1 Then ak, converge quartically to 1/π. This algorithm, together with the Salamin-Brent scheme, has been employed in numerous computations of π. Both this and the Salamin-Brent scheme are based on the arithmetic-geometric mean and some ideas due to Gauss, but evidently he (nor anyone else until 1976) ever saw the connection to computation. Perhaps no one in the pre-computer age was accustomed to an “iterative” algorithm? Ref: J. M. Borwein and P. B. Borwein, Pi and the AGM: A Study in Analytic Number Theory and Computational Complexity}, John Wiley, New York, 1987. 2 A quartically convergent algorithm for square roots I have found a quartically convergent algorithm for square roots in a little-known manuscript: · To compute the square root of q, let x0 be the initial approximation. -

Thermodynamics of Spacetime: the Einstein Equation of State

gr-qc/9504004 UMDGR-95-114 Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State Ted Jacobson Department of Physics, University of Maryland College Park, MD 20742-4111, USA [email protected] Abstract The Einstein equation is derived from the proportionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat, entropy, and temperature. The key idea is to demand that this relation hold for all the local Rindler causal horizons through each spacetime point, with δQ and T interpreted as the energy flux and Unruh temperature seen by an accelerated observer just inside the horizon. This requires that gravitational lensing by matter energy distorts the causal structure of spacetime in just such a way that the Einstein equation holds. Viewed in this way, the Einstein equation is an equation of state. This perspective suggests that it may be no more appropriate to canonically quantize the Einstein equation than it would be to quantize the wave equation for sound in air. arXiv:gr-qc/9504004v2 6 Jun 1995 The four laws of black hole mechanics, which are analogous to those of thermodynamics, were originally derived from the classical Einstein equation[1]. With the discovery of the quantum Hawking radiation[2], it became clear that the analogy is in fact an identity. How did classical General Relativity know that horizon area would turn out to be a form of entropy, and that surface gravity is a temperature? In this letter I will answer that question by turning the logic around and deriving the Einstein equation from the propor- tionality of entropy and horizon area together with the fundamental relation δQ = T dS connecting heat Q, entropy S, and temperature T . -

Unit 2. Powers, Roots and Logarithms

English Maths 4th Year. European Section at Modesto Navarro Secondary School UNIT 2. POWERS, ROOTS AND LOGARITHMS. 1. POWERS. 1.1. DEFINITION. When you multiply two or more numbers, each number is called a factor of the product. When the same factor is repeated, you can use an exponent to simplify your writing. An exponent tells you how many times a number, called the base, is used as a factor. A power is a number that is expressed using exponents. In English: base ………………………………. Exponente ………………………… Other examples: . 52 = 5 al cuadrado = five to the second power or five squared . 53 = 5 al cubo = five to the third power or five cubed . 45 = 4 elevado a la quinta potencia = four (raised) to the fifth power . 1521 = fifteen to the twenty-first . 3322 = thirty-three to the power of twenty-two Exercise 1. Calculate: a) (–2)3 = f) 23 = b) (–3)3 = g) (–1)4 = c) (–5)4 = h) (–5)3 = d) (–10)3 = i) (–10)6 = 3 3 e) (7) = j) (–7) = Exercise: Calculate with the calculator: a) (–6)2 = b) 53 = c) (2)20 = d) (10)8 = e) (–6)12 = For more information, you can visit http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Basic_Algebra UNIT 2. Powers, roots and logarithms. 1 English Maths 4th Year. European Section at Modesto Navarro Secondary School 1.2. PROPERTIES OF POWERS. Here are the properties of powers. Pay attention to the last one (section vii, powers with negative exponent) because it is something new for you: i) Multiplication of powers with the same base: E.g.: ii) Division of powers with the same base : E.g.: E.g.: 35 : 34 = 31 = 3 iii) Power of a power: 2 E.g. -

The Ordered Distribution of Natural Numbers on the Square Root Spiral

The Ordered Distribution of Natural Numbers on the Square Root Spiral - Harry K. Hahn - Ludwig-Erhard-Str. 10 D-76275 Et Germanytlingen, Germany ------------------------------ mathematical analysis by - Kay Schoenberger - Humboldt-University Berlin ----------------------------- 20. June 2007 Abstract : Natural numbers divisible by the same prime factor lie on defined spiral graphs which are running through the “Square Root Spiral“ ( also named as “Spiral of Theodorus” or “Wurzel Spirale“ or “Einstein Spiral” ). Prime Numbers also clearly accumulate on such spiral graphs. And the square numbers 4, 9, 16, 25, 36 … form a highly three-symmetrical system of three spiral graphs, which divide the square-root-spiral into three equal areas. A mathematical analysis shows that these spiral graphs are defined by quadratic polynomials. The Square Root Spiral is a geometrical structure which is based on the three basic constants: 1, sqrt2 and π (pi) , and the continuous application of the Pythagorean Theorem of the right angled triangle. Fibonacci number sequences also play a part in the structure of the Square Root Spiral. Fibonacci Numbers divide the Square Root Spiral into areas and angle sectors with constant proportions. These proportions are linked to the “golden mean” ( golden section ), which behaves as a self-avoiding-walk- constant in the lattice-like structure of the square root spiral. Contents of the general section Page 1 Introduction to the Square Root Spiral 2 2 Mathematical description of the Square Root Spiral 4 3 The distribution -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

My Favourite Problem No.1 Solution

My Favourite Problem No.1 Solution First write on the measurements given. The shape can be split into different sections as shown: d 8 e c b a 10 From Pythagoras’ Theorem we can see that BC2 = AC2 + AB2 100 = 64 + AB2 AB = 6 Area a + b + c = Area of Semi-circle on BC (radius 5) = Area c + d = Area of Semi-circle on AC (radius 4) = Area b + e = Area of Semi-circle on AB (radius 3) = Shaded area = Sum of semi-circles on AC and AB – Semi-circle on BC + Triangle Area d + e = d + c + b + e - (a + b + c ) + a = + - + = = 24 (i.e. shaded area is equal to the area of the triangle) The final solution required is one third of this area = 8 Surprisingly you do not need to calculate the areas of the semi-circles as we can extend the use of Pythagoras’ Theorem for other shapes on the three sides of a right-angled triangle. Triangle ABC is a right-angled triangle, so the sum of the areas of the two smaller semi-circles is equal to the area of the larger semi-circle on the hypotenuse BC. Consider a right- angled triangle of sides a, b and c. Then from Pythagoras’ Theorem we have that the square on the hypotenuse is equal to c a the sum of the squares on the other two sides. b Now if you multiply both sides by , this gives c which rearranges to . a b This can be interpreted as the area of the semi-circle on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the areas of the semi-circles on the other two sides. -

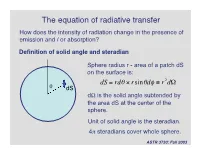

The Equation of Radiative Transfer How Does the Intensity of Radiation Change in the Presence of Emission and / Or Absorption?

The equation of radiative transfer How does the intensity of radiation change in the presence of emission and / or absorption? Definition of solid angle and steradian Sphere radius r - area of a patch dS on the surface is: dS = rdq ¥ rsinqdf ≡ r2dW q dS dW is the solid angle subtended by the area dS at the center of the † sphere. Unit of solid angle is the steradian. 4p steradians cover whole sphere. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Definition of the specific intensity Construct an area dA normal to a light ray, and consider all the rays that pass through dA whose directions lie within a small solid angle dW. Solid angle dW dA The amount of energy passing through dA and into dW in time dt in frequency range dn is: dE = In dAdtdndW Specific intensity of the radiation. † ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Compare with definition of the flux: specific intensity is very similar except it depends upon direction and frequency as well as location. Units of specific intensity are: erg s-1 cm-2 Hz-1 steradian-1 Same as Fn Another, more intuitive name for the specific intensity is brightness. ASTR 3730: Fall 2003 Simple relation between the flux and the specific intensity: Consider a small area dA, with light rays passing through it at all angles to the normal to the surface n: n o In If q = 90 , then light rays in that direction contribute zero net flux through area dA. q For rays at angle q, foreshortening reduces the effective area by a factor of cos(q). -

Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics

chapter 8 Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics F. Javier Campos-Daroca 1 Socrates vs. Epicurus: Ancients and Moderns According to an ancient genre of philosophical historiography, Epicurus and Socrates belonged to distinct traditions or “successions” (diadochai) of philosophers. Diogenes Laertius schematizes this arrangement in the following way: Socrates is placed in the middle of the Ionian tradition, which starts with Thales and Anaximander and subsequently branches out into different schools of thought. The “Italian succession” initiated by Pherecydes and Pythagoras comes to an end with Epicurus.1 Modern views, on the other hand, stress the contrast between Socrates and Epicurus as one between two opposing “ideal types” of philosopher, especially in their ways of teaching and claims about the good life.2 Both ancients and moderns appear to agree on the convenience of keeping Socrates and Epicurus apart, this difference being considered a fundamental lineament of ancient philosophy. As for the ancients, however, we know that other arrangements of philosophical traditions, ones that allowed certain connections between Epicureanism and Socratism, circulated in Hellenistic times.3 Modern outlooks on the issue are also becoming more nuanced. 1 DL 1.13 (Dorandi 2013). An overview of ancient genres of philosophical history can be seen in Mansfeld 1999, 16–25. On Diogenes’ scheme of successions and other late antique versions of it, see Kienle 1961, 3–39. 2 According to Riley 1980, 56, “there was a fundamental difference of opinion concerning the role of the philosopher and his behavior towards his students.” In Riley’s view, “Epicurean criticism was concerned mainly with philosophical style,” not with doctrines (which would explain why Plato was not as heavily attacked as Socrates). -

Area of Polygons and Complex Figures

Geometry AREA OF POLYGONS AND COMPLEX FIGURES Area is the number of non-overlapping square units needed to cover the interior region of a two- dimensional figure or the surface area of a three-dimensional figure. For example, area is the region that is covered by floor tile (two-dimensional) or paint on a box or a ball (three- dimensional). For additional information about specific shapes, see the boxes below. For additional general information, see the Math Notes box in Lesson 1.1.2 of the Core Connections, Course 2 text. For additional examples and practice, see the Core Connections, Course 2 Checkpoint 1 materials or the Core Connections, Course 3 Checkpoint 4 materials. AREA OF A RECTANGLE To find the area of a rectangle, follow the steps below. 1. Identify the base. 2. Identify the height. 3. Multiply the base times the height to find the area in square units: A = bh. A square is a rectangle in which the base and height are of equal length. Find the area of a square by multiplying the base times itself: A = b2. Example base = 8 units 4 32 square units height = 4 units 8 A = 8 · 4 = 32 square units Parent Guide with Extra Practice 135 Problems Find the areas of the rectangles (figures 1-8) and squares (figures 9-12) below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 2 mi 5 cm 8 m 4 mi 7 in. 6 cm 3 in. 2 m 5. 6. 7. 8. 3 units 6.8 cm 5.5 miles 2 miles 8.7 units 7.25 miles 3.5 cm 2.2 miles 9. -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes.