Henoch-Schönlein Purpura Secondary to Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Successful Management of a Rare Presentation

Indian J Crit Care Med July-September 2008 Vol 12 Issue 3 Case Report Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and systemic lupus erythematosus: Successful management of a rare presentation Pratish George, Jasmine Das, Basant Pawar1, Naveen Kakkar2 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) very rarely present simultaneously and pose a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma to the critical care team. Prompt diagnosis and management with plasma exchange and immunosuppression is life-saving. A patient critically ill with TTP and SLE, successfully managed in the acute period of illness with plasma exchange, steroids and Abstract mycophenolate mofetil is described. Key words: Plasma exchange, systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Introduction Case Report Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) is diagnosed by A 30-year-old lady was admitted with fever and the presence of four or more of the following criteria, jaundice. A week earlier she had undergone an serially or simultaneously: malar rash, discoid rash, uncomplicated medical termination of pregnancy at photosensitivity, oral ulcers, non erosive arthritis, serositis, another hospital, at 13 weeks of gestation. She had an renal abnormalities including proteinuria or active urinary uneventful pregnancy with twins two years earlier and sediments, neuropsychiatric features, hematological the twins were diagnosed to have thalassemia major. abnormalities including hemolytic anemia, leucopenia, She was subsequently diagnosed to have thalassemia lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, immunological minor and her husband had thalassemia minor trait. No markers like anti-ds DNA or anti-Smith antibody and high earlier history of spontaneous Þ rst trimester abortions Antinuclear antibody titres. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic was present. purpura (TTP) in patients with SLE is extremely rare. -

Immune-Pathophysiology and -Therapy of Childhood Purpura

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;7(1):3-13. Review article Immune-pathophysiology and -therapy of childhood purpura Safinaz A Elhabashy Professor of Pediatrics, Ain Shams University, Cairo Childhood purpura - Overview vasculitic disorders present with palpable Purpura (from the Latin, purpura, meaning purpura2. Purpura may be secondary to "purple") is the appearance of red or purple thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, discolorations on the skin that do not blanch on coagulation factor deficiency or vascular defect as applying pressure. They are caused by bleeding shown in table 1. underneath the skin. Purpura measure 0.3-1cm, A thorough history (Table 2) and a careful while petechiae measure less than 3mm and physical examination (Table 3) are critical first ecchymoses greater than 1cm1. The integrity of steps in the evaluation of children with purpura3. the vascular system depends on three interacting When the history and physical examination elements: platelets, plasma coagulation factors suggest the presence of a bleeding disorder, and blood vessels. All three elements are required laboratory screening studies may include a for proper hemostasis, but the pattern of bleeding complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, depends to some extent on the specific defect. In prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial general, platelet disorders manifest petechiae, thromboplastin time (aPTT). With few exceptions, mucosal bleeding (wet purpura) or, rarely, central these studies should identify most hemostatic nervous system bleeding; -

Thrombocytopenia.Pdf

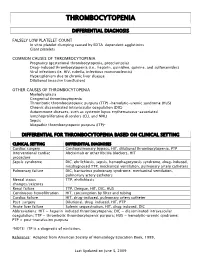

THROMBOCYTOPENIA DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FALSELY LOW PLATELET COUNT In vitro platelet clumping caused by EDTA-dependent agglutinins Giant platelets COMMON CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Pregnancy (gestational thrombocytopenia, preeclampsia) Drug-induced thrombocytopenia (i.e., heparin, quinidine, quinine, and sulfonamides) Viral infections (ie. HIV, rubella, infectious mononucleosis) Hypersplenism due to chronic liver disease Dilutional (massive transfusion) OTHER CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Myelodysplasia Congenital thrombocytopenia Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) -hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) Chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (CLL and NHL) Sepsis Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)* DIFFERENTIAL FOR THROMBOCYTOPENIA BASED ON CLINICAL SETTING CLINICAL SETTING DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES Cardiac surgery Cardiopulmonary bypass, HIT, dilutional thrombocytopenia, PTP Interventional cardiac Abciximab or other IIb/IIIa blockers, HIT procedure Sepsis syndrome DIC, ehrlichiosis, sepsis, hemophagocytosis syndrome, drug-induced, misdiagnosed TTP, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Pulmonary failure DIC, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Mental status TTP, ehrlichiosis changes/seizures Renal failure TTP, Dengue, HIT, DIC, HUS Continuous hemofiltration HIT, consumption by filter and tubing Cardiac failure HIT, drug-induced, pulmonary artery catheter Post-surgery -

Pathobiology of Thrombocytopenia and Bleeding in Patients with Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome

TITLE: Pathobiology of Thrombocytopenia and Bleeding in Patients with Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Principal Investigator: James B. Bussel, MD IRB Protocol Number: 0801009600 ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT00909363 Compound Number: SB-497115 Development Phase: Phase II Effective Date: August 26th 2010 Updated: September 18, 2015 Protocol Versions: August 15, 2013 October 28, 2014 December 31, 2014 July 7, 2015 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Background 5 1.2 Rationale 5 2 OBJECTIVE(S) 6 2.1 Primary Objective 6 2.2 Secondary Objectives 6 3 INVESTIGATIONAL PLAN 6 3.1 Study Design 6 3.2 Laboratory Testing 7 4 SUBJECT SELECTION AND WITHDRAWAL CRITERIA 8 4.1 Number of Subjects 8 4.2 Inclusion Criteria 8 4.3 Exclusion Criteria 8 4.4 Withdrawal Criteria 9 4.4.1 Study Stopping Rules 10 4.4.2 Patient Stopping Rules 10 5 STUDY TREATMENTS 10 5.1 Treatment Assignment 10 5.2 Product Accountability 11 5.3 Treatment Compliance 11 5.4 Concomitant Medications and Non-Drug Therapies 11 5.4.1 Permitted Medications and Non-Drug Therapies 11 5.4.2 Prohibited Medications and Non-Drug Therapies 11 5.5 Treatment after the End of the Study 11 5.6 Treatment of Investigational Product Overdose 11 5.7 Treatment Plan 12 6 STUDY ASSESSMENTS AND PROCEDURES 13 6.1 Critical Baseline Assessments 13 6.2 Efficacy 13 6.3 Safety 13 6.3.1 Liver chemistry stopping and follow-up criteria 15 6.4 Adverse Events 16 6.4.1 Definition of an AE 16 6.4.2 Definition of a SAE 17 6.4.3 Disease-Related Events and/or Disease-Related Outcomes Not Qualifying as SAEs -

Acute Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura in Children

Turk J Hematol 2007; 24:41-51 REVIEW ARTICLE © Turkish Society of Hematology Acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children Abdul Rehman Sadiq Public School, Bahawalpur, Pakistan [email protected] Received: Sep 12, 2006 • Accepted: Mar 21, 2007 ABSTRACT Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in children is usually a benign and self-limiting disorder. It may follow a viral infection or immunization and is caused by an inappropriate response of the immune system. The diagnosis relies on the exclusion of other causes of thrombocytopenia. This paper discusses the differential diagnoses and investigations, especially the importance of bone marrow aspiration. The course of the disease and incidence of intracranial hemorrhage are also discussed. There is substantial discrepancy between published guidelines and between clinicians who like to over-treat. The treatment of the disease ranges from observation to drugs like intrave- nous immunoglobulin, steroids and anti-D to splenectomy. The different modes of treatment are evaluated. The best treatment seems to be observation except in severe cases. Key Words: Thrombocytopenic purpura, bone marrow aspiration, Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, steroids, anti-D immunoglobulins 41 Rehman A INTRODUCTION There is evidence that enhanced T-helper cell/ Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in APC interactions in patients with ITP may play an children is usually a self-limiting disorder. The integral role in IgG antiplatelet autoantibody pro- American Society of Hematology (ASH) in 1996 duction -

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) — Adult Conditions for Which Ivig Has an Established Therapeutic Role

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) — adult Conditions for which IVIg has an established therapeutic role. Specific Conditions Newly Diagnosed Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Persistent Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Chronic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Evans syndrome ‐ with significant Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) ‐ adult Indication for IVIg Use Newly diagnosed ITP — initial Ig therapy ITP in pregnancy — initial Ig therapy ITP with life‐threatening haemorrhage or the potential for life‐threatening haemorrhage Newly diagnosed or persistent ITP — subsequent therapy (diagnosis <12 months) Refractory persistent or chronic ITP — splenectomy failed or contraindicated and second‐line agent unsuccessful Subsequent or ongoing treatment for ITP responders during pregnancy and the postpartum period ITP and inadequate platelet count for planned surgery HIV‐associated ITP Level of Evidence Evidence of probable benefit – more research needed (Category 2a) Description and Diagnostic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is a reduction in platelet count Criteria (thrombocytopenia) resulting from shortened platelet survival due to anti‐platelet antibodies, reduced platelet production due to immune induced reduced megakaryopoeisis and/or immune mediated direct platelet lysis. When counts are very low (less than 30x109/L), bleeding into the skin (purpura) and mucous membranes can occur. Bone marrow platelet production (megakaryopoiesis) is morphologically normal. In some cases, there is additional impairment of platelet function related to antibody binding to glycoproteins on the platelet surface. It is a common finding in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, and while it may be found at any stage of the infection, its prevalence increases as HIV disease advances. Around 80 percent of adults with ITP have the chronic form of disease. -

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management Senthil Sukumar 1 , Bernhard Lämmle 2,3,4 and Spero R. Cataland 1,* 1 Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Hematology and Central Hematology Laboratory, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, CH 3010 Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, University Medical Center, Johannes Gutenberg University, 55131 Mainz, Germany 4 Haemostasis Research Unit, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare thrombotic microangiopathy charac- terized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, severe thrombocytopenia, and ischemic end organ injury due to microvascular platelet-rich thrombi. TTP results from a severe deficiency of the specific von Willebrand factor (VWF)-cleaving protease, ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 repeats, member 13). ADAMTS13 deficiency is most commonly acquired due to anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies. It can also be inherited in the congenital form as a result of biallelic mutations in the ADAMTS13 gene. In adults, the condition is most often immune-mediated (iTTP) whereas congenital TTP (cTTP) is often detected in childhood or during pregnancy. iTTP occurs more often in women and is potentially lethal without prompt recognition and treatment. Front-line therapy includes daily plasma exchange with fresh frozen plasma replacement and im- munosuppression with corticosteroids. Immunosuppression targeting ADAMTS13 autoantibodies Citation: Sukumar, S.; Lämmle, B.; with the humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab is frequently added to the initial ther- Cataland, S.R. -

A 61-Year-Old Woman with Thrombocytopenia and a Rash

A SELF-TEST IM BOARD REVIEW DAVID L. LONGWORTH, MD, JAMES K STOLLER, MD, EDITORS OF CLINICAL PETER MAZZONE, MD CRAIG NIELSEN, MD RECOGNITION Department of General Internal Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, 1 Cleveland Clinic. Cleveland Clinic. A 61-year-old woman with thrombocytopenia and a rash 61-YEAR-OLD WOMAN with a history of rate 20. She was not in acute distress. 0seizures was transferred to our facility Examination of her skin revealed confluent from another hospital for further evaluation macular purpuric lesions involving the entire and management of a rash and a low platelet body and face, with relative sparing of the count. palms and soles. Purpuric papules were also The woman was initially admitted to the found on the back of her hands and legs. other hospital 4 weeks earlier due to the onset There was also conjunctival injection with of focal seizures. An extensive evaluation periorbital edema, but mucous membranes revealed no etiology for the seizures. She was were clear. The chest was normal on ausculta- discharged home with her seizures well con- tion, and no wheezes were heard. Her cardiac trolled with phenytoin. Approximately 3 examination was normal. There was no weeks later, she noticed a diffuse rash without detectable organomegaly, and a stool test for any other associated symptoms. Her primary occult blood was positive. She had strong physician discontinued the phenytoin and peripheral pulses with no edema. substituted carbamazepine. Two days later she felt that her rash had worsened, and she • LABORATORY RESULTS AT ADMISSION became frustrated and stopped taking all of Platelet her medications. -

WISKOTT-ALDRICH SYNDROME and X-LINKED THROMBOCYTOPENIA Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment

ITALIAN PRIMARY IMMUNODEFICIENCIES STRATEGIC SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE WISKOTT-ALDRICH SYNDROME AND X-LINKED THROMBOCYTOPENIA Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment Update: January 2004 Cohordinator Primary Prof. Alberto G. Ugazio Immunodeficiencies Network: Ospedale Bambin Gesù Roma Scientific Committee: Dott. M. Aricò (Palermo) Prof. L. Armenio (Bari) Prof. C. Azzari (Firenze) Prof. G. Basso (Padova) Prof. D. De Mattia (Bari) Dott. C. Dufour (Genova) Prof. M. Duse (Brescia) Prof. R. Galanello (Cagliari) Prof. A. Iolascon (Napoli) Dott. M. Jankovic (Monza) Dott. F. Locatelli (Pavia) Prof. GL Marseglia (Pavia) Prof. M. Masi (Bologna) Prof. G. Paolucci (Bologna) Prof. A. Pession (Bologna) Prof. MC Pietrogrande (Milano) Prof. C. Pignata (Napoli) Prof. A. Plebani (Brescia) Prof. V. Poggi (Napoli) Dott. F. Porta (Brescia) Prof. I. Quinti (Roma) Prof. U. Ramenghi (Torino) Prof. P. Rossi (Roma) Prof. G. Schilirò (Catania) Prof. A. Stabile (Roma) Prof. PA Tovo (Torino) Prof. A. Ventura (Trieste) Prof. A. Vierucci (Firenze) 2 Responsible: Prof. Luigi D. Notarangelo Dott.ssa Annarosa Soresina Clinica Pediatrica Università degli Studi di Brescia Ospedale dei Bambini – Spedali Civili Brescia Writing: Prof. Luigi D. Notarangelo Dott.ssa Annarosa Soresina Data Review Committee: Prof. Luigi D. Notarangelo (BS) Dott.ssa Annarosa Soresina (BS) Dott. Roberto Rondelli (BO) Data management and analysis: Centro Operativo AIEOP Pad. 23 c/o Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerche sul Cancro “G. Prodi” Via Massarenti, 9 40138 Bologna 3 CENTRES CODE AIEOP INSTITUTION RAPRESENTATIVE 0901 ANCONA Prof. Coppa Clinica Pediatrica Prof. P.Pierani Ospedale Salesi ANCONA Tel.071/36363 Fax 071/36281 0311 ASOLA(MN) Dott.G.Gambaretto Divisione di Pediatria Ospedale di Asola Tel. 0376/721309 Fax 0376/720189 1301 BARI Prof. -

Current Status in Diagnosis and Treatment of Hereditary Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Hayley a Hanby2 and X

tics: Cu ne rr e en G t y R r e a t s i e d a e r r c e h Hanby and Zheng, Hereditary Genet 2014, 3:1 H Hereditary Genetics DOI: 10.4172/2161-1041.1000e108 ISSN: 2161-1041 Editorial Open Access Current Status in Diagnosis and Treatment of Hereditary Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Hayley A Hanby2 and X. Long Zheng1,2* 11Deparment of Cell and Molecular Biology Graduate Group, The University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine Philadelphia, PA, USA 2 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, PA, USA *Corresponding author: X. Long Zheng, The University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, USA, PA 19104, Tel: 215-590-3565; Fax: 267-426-5165;E-mail:[email protected] Rec date: April 09, 2014, Acc date: April 09, 2014, Pub date: April 11, 2014 Copyright: © 2014 Hanby HA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Editorial lactate dehydrogenase, and fragmentation of red blood cells) with or without organ dysfunctions including central nerve system, cardiac, Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) is an acute and and renal. If available, plasma ADAMTS13 activity and inhibitor tests potentially fatal hematologic disorder. It is characterized by systemic are important for the differentiation of TTP from a similar syndrome, platelet clumping in the microvasculature and small arterioles, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) [19]. Unlike classic HUS resulting in thrombocytopenia and microangiopathic hemolytic that is commonly caused by toxin-producing E. -

Iga Vasculitis in Children: Beyond the Rash

Pediatric Urgent Care IgA Vasculitis in Children: Beyond the Rash Urgent message: While most cases of IgA vasculitis are benign, it is essential for the urgent care provider to screen for complications, such as gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intussusception, and nephritis, as well as for renal disease. DIANA SOFIA VILLACIS NUNEZ, MD; AMIT THAKRAL, MD, MBA; and PAREEN SHAH, MD Case Presentation 12-year-old previously healthy female presents with A a 5-day history of lower extremity rash and low- grade fever (100.6°F). A month earlier, she had a self- resolving viral upper respiratory infection. The rash is described as mildly pruritic, dark red spots which started on her feet and spread upwards to her thighs. Associated symptoms include decreased appetite, bilateral ankle pain and swelling, bilateral feet swelling, and refusal to walk. Patient did not complain of abdominal pain, nau- sea, vomiting, headaches, dizziness, dysuria, hematuria, hematochezia, or melena. Therapy at home included ibuprofen as needed for pain and diphenhydramine for pruritus. At initial presentation in the urgent care center, she was afebrile (98.6°F) with a heart rate of 101 beats/mi- nute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute, blood pres- sure of 123/79 mmHg, and an oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. Physical examination showed a pal- ©AdobeStock.com pable, purpuric, non-blanching rash, most prominent on the lower legs and ankles (Figures 1a and 1b). Her vasculitis in childhood, affecting eight to 20 per 100,000 ankles were notable for joint effusions bilaterally with- children each year, accounting for roughly 50% of pe- out erythema. -

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Or Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation? Diagnostic Dilemma in the ICU

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine 2012-03-24 Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura or Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation? Diagnostic Dilemma in the ICU Lindsay Gittens University of Massachusetts Medical School Et al. Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/anesthesiology_pubs Part of the Anesthesiology Commons Repository Citation Gittens L, Metcalf K, Watson NC. (2012). Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura or Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation? Diagnostic Dilemma in the ICU. Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications. https://doi.org/10.13028/c0xd-kf89. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/ anesthesiology_pubs/120 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Publications by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura or Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation? Diagnostic Dilemma in the ICU Lindsay Gittens MSIV, Katherine Metcalf M.D., Nicholas C. Watson M.D. Department of Anesthesiology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA Background Figure 1. Hospital Course of Thrombocytopenia Figure 3. Weighing the Data Discussion Baseline HD1 HD2 HD3 HD4 HD5 HD6 HD7 HD8 HD9 DIC and TTP are two causes of thrombocytopenia that require Figure 3. Summary of the lab values for the patient The clinical differentiation between DIC and TTP can be a timely diagnosis and different treatments. Both conditions can be presented here. Note that because of the numerous platelets 310 111 53 48 24 25 21 41 76 153 supporting features for TTP and DIC, it was not until diagnostic challenge.