Pittsburgh's Third PBIDA Conference an Outstanding Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

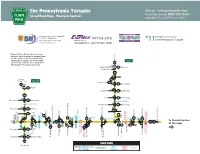

Simple Maps of the Pennsylvania Turnpike System

The Pennsylvania Turnpike Website: www.paturnpike.com Customer Service: 800.331.3414 (Outside U.S., call 717.831.7601) Travel Information: Dial 511 within PA Emergency Assistance or 1-877-511-PENN(7366) (877.736 .6727) when calling from outside of PA, Customer Service *11on the Pennsylvania Turnpike or visit www.511pa.com (Outside U.S., call 717-561-1522) *Gateway Toll Plaza (#2) near Ohio is a one-way toll facility. No toll is charged for westbound travel into Ohio, but there is an eastbound toll to enter Delmont Greensburg Pennsylvania via Gateway. The one-way tolling Bypass conversion was required to ease congestion and 66 allow installation of Express E-ZPass lanes. 14 Murrysville 22 Blairsville Sheffield D r. 66 12 BUS Sharon, Beaver Valley 66 Youngstown Expressway Harrison City 993 9 BUS Greensburg 376 15 66 422 Butler 8 Jeannette 130 Greensburg 376 6 Irwin 30 Greensburg 17 Mt. Jackson 108 New Castle Mainline Toll Zone 4 Mainline Toll Zone West Newton 136 Greensburg 20 New Galilee 168 Moravia 1 Erie Arona Rd. 351 Butler Ligonier Murrysville New Kensington Johnstown Greensburg 119 19 0 26 Elwood City ALLEGHENY 28 PITTSBURGH IRWIN DONEGAL 711 SOMERSET VALLEY 22 57 30 NEW STANTON 601 48 67 New Stanton Service Plaza 91 110 N.Somerset Service Plaza Allegheny Tunnel Warrendale Toll Plaza Allegheny River Allegheny Gateway Toll Plaza (Eastbound Only)* 75 Beaver River Beaver 49 To Central Section 76 70 76 Ohio 2 30 78 NEW BEAVER CRANBERRY BUTLER 112 of the map CASTLE 18 VALLEY 28 VALLEY 70 119 31 10 13 8 39 29 79 376 Darlington 551 Beaver -

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B

The Syrian Community in New Castle and Its Unique Alawi Component, 1900-1940 Anthony B. Toth L Introduction and immigration are two important and intertwined phenomena in Pennsylvania's history from 1870 to INDUSTRIALIZATIONWorld War II.The rapid growth of mining, iron and steel pro- duction, manufacturing, and railroads during this period drew millions of immigrants. In turn, the immigrants had a significant effect on their towns and cities. The largest non-English-speaking— groups to jointhe industrial work force — the Italians and Poles have been the sub- jects of considerable scholarly attention. 1 Relatively little, however, has been published about many of the smaller but still significant groups that took part in the "new immigration/' New Castle's Syrian community is one such smaller group. 2 In a general sense, it is typical of other Arabic-speaking immigrant com- munities which settled inAmerican industrial centers around the turn of the century — Lawrence, Fall River, and Springfield, Mass.; Provi- Writer and editor Anthony B. Toth earned his master's degree in Middle East history from Georgetown University. He performed the research for this article while senior writer for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee Re- search Institute. He has also written articles on the Arab-American communities in Jacksonville, Florida, and Worcester, Massachusetts. —Editor 1 Anyone researching the history of immigrants and Pennsylvania industry cannot escape the enlightening works of John E.Bodnar, who focuses main- ly on the Polish and Italian experiences. In particular, see his Workers' World: Kinship, Community and Protest in an Industrial Society, 1900- 1940 (Baltimore, 1982); Immigration and Industrialization: Ethnicity in an American MillTown, 1870-1940 (Pittsburgh, —1977); and, with Roger Simon and Michael P. -

Philadelphia-Area Schools Rise to the Challenge

PRIVATE SCHOOL GUIDE FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF PHILADELPHIA MAGAZINE 20 20 PRIVATE SCHOOLS REGIONAL GUIDE PRIVATE EDUCATION 101 THE FINAL MONTHS OF THE 2020 SCHOOL YEAR challenged PHILADELPHIA-AREA SCHOOLS educators like never before. In this year’s Private School Guide, you’ll hear how local schools excelled in educating and caring for students virtually amid the coronavirus pandemic RISE TO THE CHALLENGE and get pro tips for choosing the right school without in- With small class sizes, the latest technology and person tours. You’ll also discover some of the region's most tight-knit communities, the appeal of a private innovative and exciting schools for your child—whether they need extra academic challenges, an inclusive community or school education has never been more clear. support to thrive with their learning differences. PHILLYMAG.COM/PRIVATESCHOOLGUIDE 19 Sponsor Content / PRIVATE SCHOOL GUIDE ACADEMICS Other schools adapted by flipping how THE RESULTS students learn—having them review materials first, followed by in-class 20 20 ARE IN instruction with the teacher. “Some- times, it can be easy to default to having Faced with an unprecedented test, information spoon-fed to you, but in a PRIVATE SCHOOLS local private schools have received virtual classroom, you need to own it REGIONAL GUIDE high marks on remote learning. more,” says Daniel Ranalli, an assistant principal at Saint Joseph’s Preparatory This past spring, students, teachers, School in Philadelphia. “That is a great parents and administrators from the skill to have when you move on to college ADMISSIONS Greater Philadelphia region all partook and beyond.” in one giant learning experiment—and Across the board, regional private not the kind that takes place in a science schools saw remote learning as an op- Making lab. -

August 12, 2020 Allentown City Council 435

August 12, 2020 Allentown City Council 435 Hamilton Street Allentown, PA 18101 Eastern Region Office (610) 437-7555 PO Box 60173 By fax to (610) 437-7554 Philadelphia, PA 19102 By email to 215-592-1513 T 215-592-1343 F [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Central Region Office PO Box 11761 [email protected] Harrisburg, PA 17108 [email protected] 717-238-2258 T [email protected] 717-236-6895 F [email protected] Western Region Office PO Box 23058 Re: Resolution 86 and District Attorney Martin’s Memorandum Pittsburgh, PA 15222 in Response 412-681-7736 T 412-681-8707 F To Council President Hendricks, Council Vice-President Guridy, and Council Members Affa, Gerlach, Mota, Siegel and Zucal: The American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania has been made aware of the memorandum written by District Attorney Martin in opposition to proposed Resolution No. 86, which details Community Strategies for Police Oversight Review and Recommendations. Unfortunately, in raising his concerns, District Attorney Martin seems to have misinterpreted Pennsylvania law and its applicability. Based on growing community demands for police reform, Resolution No. 86 proposes to begin a dialogue on various police reform proposals. Several of these reforms originate from the Eight Can’t Wait agenda, which have been adopted by municipalities and police professionals from across the country, including by other officials in Pennsylvania. The Resolution does not mandate the adoption of any specific proposal at this time, but would only commit the City Council to make recommendations based on these discussions within three months—with the aim to produce legislation on any accepted recommendations. -

Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and the Elusive Quest for a New Deal Majority in the Keystone State

A Tale of Two Cities: Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and the Elusive Quest for a New Deal Majority in the Keystone State The Needs of the Many . N RETROSPECT, the formation of a Democratic electoral majority in the 1930s—one that ruled American politics for two generations— Iseems almost to have been inevitable. The Great Depression, and then a world war, enabled Franklin D. Roosevelt to lay the foundations of the modern welfare state, drive much of the public policy debate, and unite Americans in war—and to some extent in peace. But a careful study of the national scene, as well as sensitivity to the nuances of community and state politics in Pennsylvania, paints a different picture. The New Deal coalition was comprised of various interests with little in common beyond shared poverty and a profound admiration for President Roosevelt. Segregationist white southerners, northern blacks, Jews, Catholics, and unskilled workers who enlisted in the affiliates of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) maintained a tenuous alliance brokered by Roosevelt. On more than a few occasions, the New Deal coalition faltered, leading to both local and national Republican vic- tories. Due to effective organization, cultural preferences, and political habit, among other factors, Republicans remained viable, and even strong, in states such as Pennsylvania. Essential to Democratic victory were the children of southern and eastern European Roman Catholic and Jewish immigrants who clustered in the urban industrial centers of the North. With the advent of federal immigration-restriction legislation in 1921 (and again in 1924), ethnic urban wards largely ceased to be centers of transient male workers who had little desire to follow the moral exhortations of clergy, join labor THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. -

Navigating the Maze of Philly's Private Schools

PRIVATE SCHOOLS FROM THE PUBLISHERS OF PHILADELPHIA MAGAZINE 20 19 PRIVATE SCHOOLS REGIONAL GUIDE PRIVATE SCHOOLS 101 WITH SUCH A WEALTH OF OPTIONS, however, it can be hard to NAVIGATING THE MAZE OF know where to begin. Whether you’re looking for an elemen- tary school that will provide more support to your struggling child or a high school with exciting opportunities for your PHILLY’S PRIVATE SCHOOLS young adult, here’s a helpful guide to the Philadelphia With small class sizes, impressive facilities and region’s private schools. All it takes to ensure the best possible tight-knit communities, the appeal of a private fi t for your child is a bit of research, some careful planning, school education is clear. and an open mind to the innumerable opportunities private schools can aff ord. PHILLYMAG.COM/PRIVATESCHOOLGUIDE 55 Sponsor Content / PRIVATE SCHOOL GUIDE 20 19 PRIVATE SCHOOLS REGIONAL GUIDE ADMISSIONS 101 Acing the Application The application process can be rigorous, but with THE SEARCH Beyond that, there are also single- some preparation and sex, coeducational, boarding and organization, you’ll be well day options. on your way to a brand-new CHOOSING THE CONSIDER YOUR CHILD’S GOALS. educational experience E Is your child a budding musi- for your child. Here are a RIGHT SCHOOL cian? Do they want to be the next few things to keep in mind Jane Goodall? Or are they aiming throughout the process: “Private” is an umbrella term that for an athletic scholarship down encompasses a broad range of the line? Diff erent private schools schools that are not administered put an emphasis on research STAY ON TOP OF DEADLINES. -

Homeschooling in Pennsylvania: a Fact Sheet

HOMESCHOOLING IN PENNSYLVANIA: A FACT SHEET DOES PENNSYLVANIA ALLOW PARENTS TO TEACH THEIR CHILDREN AT HOME? Yes. Parents in Pennsylvania can teach their children at home. Pennsylvania's law on home education (also called “homeschooling”) is called Act 169. Information about this law is online at: http://www.education.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/home_education_and_ private_tutoring/20311. In Pennsylvania, children between the ages of eight and seventeen must attend school. Educating a child at home is one way to comply with compulsory school attendance laws. WHEN CAN I HOMESCHOOL MY CHILD? You can homeschool your child if: (1) the person teaching the child is a “properly qualified private tutor,” or (2) if a child’s parent or guardian conducts a “home education program” for the child. Each of these options has certain requirements. WHAT ARE THE MAIN REQUIREMENTS FOR A “PROPERLY QUALIFIED PRIVATE TUTOR?” The tutor: (1) must have a Pennsylvania teacher's certificate; (2) must be teaching “one or more children who are members of a single family;” (3) must be providing the child or children with the majority of their instruction; and (4) must be receiving some form of payment for his or her services. A private tutor must file a copy of his/her Pennsylvania teacher’s certificate and a criminal background check with the superintendent of the student’s district of residence. Private tutoring is subject to the annual approval of the superintendent. The tutoring must provide at least 180 days of instruction per year, or a minimum of 900 hours (990 hours at the secondary level) of instruction per year. -

History of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court Erie, Pennsylvania

HHiissttoorryy ooff tthhee UUnniitteedd SSttaatteess BBaannkkrruuppttccyy CCoouurrtt EErriiee,, PPeennnnssyyllvvaanniiaa BByy RRoonnaalldd EE.. CCooookk,, EEssqq.. UUppddaatteedd MMaarrcchh 22000099 CONTENTS History of the Bankruptcy Court in Erie, Pennsylvania ........................................................... 1 Bankruptcy Registers, Referees and Judges, Erie, Pennsylvania ............................................ 7 Honorable Samuel Ebenezer Woodruff, Bankruptcy Register ........................Exhibit A ........8 Honorable Joseph May Force, Bankruptcy Referee .........................................Exhibit B ......11 Honorable George M. Mason, Bankruptcy Referee ..........................................Exhibit C ......14 Honorable Ritchie T. Marsh, Bankruptcy Referee............................................Exhibit D ......16 Honorable James E. Marsh, Bankruptcy Referee .............................................Exhibit E ......18 Honorable Charles A. Mertens, Bankruptcy Referee .......................................Exhibit F ......20 Exhibit G ......21 Honorable William B. Washabaugh, Bankruptcy Judge ..................................Exhibit H ......22 Honorable Warren W. Bentz, Bankruptcy Judge .............................................Exhibit I .......24 Exhibit J .......26 Honorable Thomas P. Agresti, Bankruptcy Judge ............................................Exhibit K ......29 Exhibit L ......30 i History of the Bankruptcy Court in Erie, Pennsylvania By an Act of Congress passed in 1866, Erie was named -

RESOURCES the ARC of PENNSYLVANIA 101 South

RESOURCES THE ARC OF PENNSYLVANIA 101 South Second Street, Suite 8 Harrisburg, PA 17101 800-692-7258 www.thearcpa.org BUREAU OF SPECIAL EDUCATION’S CONSULTLINE, A PARENT HELPLINE 800-879-2301 ConsultLine personnel are available to parents and advocates of children with disabilities or children thought to be disabled to explain federal and state laws relating to special education; describe the options that are available to parents; inform the parents of procedural safeguards; identify other agencies and support services; and describe available remedies and how the parents can proceed. DISABILITIES RIGHTS NETWORK 1414 North Cameron Street Suite C Harrisburg, PA 17103 800-692-7443 (Toll-Free Voice) 877-375-7139 (TDD) 717-346-0293 (TDD) 717-236-8110 (Voice) 717-346-0293 (TDD) 717-236-0192 www.drnpa.org HISPANICS UNITED FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN (HUNE, INC.) 202 West Cecil B. Moore Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19122 215-425-6203 (Voice) 215-425-6204 (Fax) www.huneinc.org THE MENTOR PARENT PROGRAM, INC. 270 Mayfield Road Clarion, PA 16214 814-226-4151 (Voice) 888-447-1431 (Voice in PA) 800-855-1155 (TTY) 814-226-4850 (Fax) www.mentorparent.org OFFICE FOR DISPUTE RESOLUTION 6340 Flank Drive Harrisburg, PA 17112-2764 717-541-4960 (Phone) 800-222-3353 (Toll Free in PA only) 800-654-4984 (TTY) 717-657-5983 (Fax) http://ODR.pattan.net The Office for Dispute Resolution administers the mediation and due process systems statewide, and provides training and services regarding alternative dispute resolution methods. PARENT EDUCATION AND ADVOCACY LEADERSHIP -

Early History and Settlement Pattern

Chapter 2 – Early History and Settlement Pattern History Named for the Shenango River, Shenango Township was incorporated in 1796 as a part of Beaver County, Pennsylvania; Lawrence County did not yet exist. Shenango later became one of Lawrence County's original townships and quickly became one of the most populous areas, because the land was suitable for many different purposes. One of the first settlers to live in Shenango was William Carins. He came to this area in 1796 and was the man who gave Shenango its name. Carins was awarded the land after his service in the Revolutionary War; he was paid in 500 acres (200 ha) of land. Carins worked as a cloth weaver and ran a small store where he sold his goods. William Tindall was another one of Shenango's first settlers. Tindall was paid 400 acres (1.6 km2) for his service in the 1872 Lawrence County Atlas Revolutionary War. He lived to the age of 93 and was buried in the Tindall family cemetery near the "Turkey Hill" section of the township. The Tindall family cemetery is most famously known as the resting place of Mary Black, a supposed, but never proven, witch of around the same time period. Her grave is separate from the others and is the only one dug up. Shenango's largest land owner was a Philadelphia lawyer named Benjamin Chew. Chew bought up large portions of the southern extent of the township under assumed names for pennies an March 2017 Early History and Settlement Pattern Page 2-1 Shenango Township Comprehensive Development Plan acre. -

Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The analysis presented in this report was completed prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States and therefore the forecast estimates do not take into account the economic and housing market impacts of the actions taken to limit contagion of the virus. At this time, the duration and depth of the economic disruption are unclear, as are the extent and effectiveness of countermeasures. HUD will continue to monitor market conditions in the HMA and provide an updated report/addendum in the future. COMPREHENSIVE HOUSING MARKET ANALYSIS Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research As of January 1, 2020 Share on: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Comprehensive Housing Market Analysis as of January 1, 2020 Executive Summary 2 Venango Trumbull Mercer Clarion Jefferson k Lawrence Butler Mahoning Butler Armstrong ¨¦§79 ! Beaver Cranberry Columbiana Township Aliquippa Indiana OHIO ! ! ALLEGHENY RIVER OHIO RIVER Wexford ¨¦§76 Executive Summary PENNSYLVANIA Pittsburgh Hancock Findlay ! Murrysville WEST VIRGINIA WEST Township ! Allegheny Cecil Township Jefferson Housing Market Area Description ! Hills Westmoreland Cambria Brook McMurray Washington The Pittsburgh Housing Market Area (HMA), which is coterminous ! ¨¦§70 with the Pittsburgh, PA Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), includes Washington Ohio seven counties in southwestern Pennsylvania. For purposes Somerset MONONGAHELA RIVER Uniontown ! Pittsburgh HMA of this report, the HMA is divided into two submarkets: the Marshall Allegheny County Greene Surburban Submarket Allegheny County submarket, which includes the city of Pittsburgh, Fayette ! Places of Interest MARYLAND and the Suburban submarket, which includes the surrounding Monongalia Urbanized Areas Preston Garrett Major Roads Marion counties of Armstrong, Butler, Beaver, Fayette, Washington, and Wetzel Waterbodies Westmoreland. -

Health Matters Loose Ends

18B A Packet Publication The Week of Friday, December 14, 2018The Week of Friday, December 14, 2018 A Packet Publication 19B Health Matters Loose Ends Continued from Page 18B Continued from Page 15B attacks, the American Academy of Pediat- parents, siblings and other caregivers or • Noticeable contracting of the chest, angry for the next two years.” rics offers the following tips: close relatives should also receive the flu ribs or belly when breathing. “I was ready to do something more than • Do not smoke or let anyone else smoke vaccine. • Unusual anxiety or restlessness. just knitting pink hats for the Pussyhat in your home or car. If asthma is well managed, a child should • Change in skin color. Project,” said Susie. • Reduce exposure to dust mites by cov- not experience symptoms more than once or • Increased pulse. Princetonian, Joel Schwartz, became ering your child’s mattress and pillows with twice per week, symptoms should not wake • Sweating. Barbara’s partner in the goal of flipping special allergy-proof casing, washing bed- a child at night more than twice per month, • Decreased level of alertness. the 7th Congressional District from Re- ding in hot water every 1 to 2 weeks, and and a child should be able to play sports and At Penn Medicine Princeton Medical publican to Democratic. “Joel was great at vacuuming and dusting regularly. participate in physical education activities. Center, pediatricians from Children’s Hos- the data analysis, and I was a networking • Avoid pets or at least keep pets out of When Asthma Becomes an Emergen- pital of Philadelphia are on-site 24/7 to con- machine.