X004532030.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valentine Richmond History Walks Self-Guided Walk of the Oregon Hill Neighborhood

Valentine Richmond History Walks Self-Guided Walk of the Oregon Hill Neighborhood All directions are in italics. Enjoying your tour? The tour starts in front of St. Andrew's Episcopal Church, 240 S. Laurel Street Take a selfie (near the corner of Idlewood Avenue and Laurel Street). and tag us! @theValentineRVA WELCOME TO OREGON HILL The Oregon Hill Historic District extends from Cary Street to the James River and from Belvidere Street to Hollywood Cemetery and Linden Street. Oregon Hill’s name is said to have originated in the late 1850s, when a joke emerged that people who were moving into the area were so far from the center of Richmond that they might as well be moving to Oregon. By the mid-1900s, Oregon Hill was an insular neighborhood of white, blue-collar families and had a reputation as a rough area where outsiders and African-Americans, in particular, weren’t welcome. Today, Oregon Hill is home to two renowned restaurants and a racially and economically diverse population that includes long-time residents, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) students and people wanting to live in a historic part of Richmond. You’re standing in front of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, which began in 1873 as a Sunday school mission of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in downtown Richmond. The original church building, erected in 1875, was made of wood, but in 1901, it was replaced by this building. It is Gothic Revival in style, and the corner tower is 115 feet high. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. -

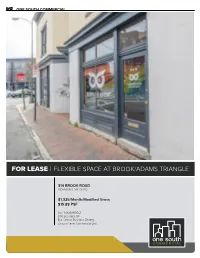

For Lease | Flexible Space at Brook/Adams Triangle

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | FLEXIBLE SPACE AT BROOK/ADAMS TRIANGLE 314 BROOK ROAD RICHMOND, VA 23220 $1,325/Month/Modified Gross $19.88 PSF PID: N0000119012 800 Leasable SF B-4 Central Business Zoning Ground Level Commercial Unit PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Arts District Storefront A perfect opportunity located right in the heart of the Brook/Adams Road triangle! This beautiful street level retail storefront boasts high ceilings, hardwood floors, exposed brick walls, and an expansive street-facing glass line. With flexible use options, this space could be a photographer studio, a small retail maker space, or the office of a local tech consulting firm. An unquestionable player in the rise of Broad Street’s revitalization efforts underway, this walkable neighborhood synergy includes such residents as Max’s on Broad, Saison, Cite Design, Rosewood Clothing Co., Little Nomad, Nama, and Gallery5. Come be a part of the creative community that is transforming Richmond’s Arts District and meet the RVA market at street level. Highlights Include: • Hardwood Floors • Exposed Brick • Restroom • Janitorial Closet • Basement Storage • Alternate Exterior Entrance ADDRESS | 314 Brook Rd PID | N0000119012 STREET LEVEL BASEMENT STOREFRONT STORAGE ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 800 SF LOCATION | Street Level STORAGE | Basement PRICE | $1,325/Mo/Modified Gross 800 SF HISTORIC LEASABLE SPACE 1912 CONSTRUCTION PRICE | $19.88 PSF *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA 314 BROOK RD | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT AREA FAN DISTRICT JACKSON WARD MONROE PARK 314 BROOK RD VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM ANN SCHWEITZER RILEY [email protected] 804.723.0446 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

Supplementary Table 10.7

Factory-made cigarettes and roll-your-own tobacco products available for sale in January 2019 at major Australian retailers1 Market Pack Number of Year Tobacco Company segment2 Brand size3 variants Variant name(s) Cigarette type introduced4 British American Super-value Rothmans5 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 2015 Tobacco Australia FMCs 23 2 Blue, Gold Regular 2018 25 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green Regular 2014 30 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 2016 40 6 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green, Black6 Regular 2014 50 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Silver, Menthol Green Regular 2016 Rothmans Cool Crush 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Flavour capsule 2017 Rothmans Superkings 20 3 Blue, Red, Menthol Green Extra-long sticks 2015 ShuangXi7 20 2 Original Red, Blue8 Regular Pre-2012 Value FMCs Holiday 20 3 Blue, Gold, Red Regular 20189 22 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Grey, Sea Green Regular Pre-2012 50 5 Blue, Gold, Red, Grey, Sea Green Regular Pre-2012 Pall Mall 20 4 Rich Blue, Ultimate Purple, Black10, Amber Regular Pre-2012 40 3 Rich Blue, Ultimate Purple, Black11 Regular Pre-2012 Pall Mall Slims 23 5 Blue, Amber, Silver, Purple, Menthol Short, slim sticks Pre-2012 Mainstream Winfield 20 6 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey, White Regular Pre-2012 FMCs 25 6 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey, White Regular Pre-2012 30 5 Blue, Gold, Sky Blue, Red, Grey Regular 2014 40 3 Blue, Gold, Menthol Fresh Regular 2017 Winfield Jets 23 2 Blue, Gold Slim sticks 2014 Winfield Optimum 23 1 Wild Mist Charcoal filter 2018 25 3 Gold, Night, Sky Charcoal filter Pre-2012 Winfield Optimum Crush 20 -

Fan District 24 Unit Multifamily

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL DRAFT 607 E BROADWAY FOR SALE | FAN DISTRICT 24 UNIT MULTIFAMILY 2700 IDLEWOOD AVE RICHMOND, VA 23220 $3,600,000 PID: W0001198007 7,500 SF Parcel 13,095 SF Building Area 3,273 SF Basement Area 3 Stories 24 Residential Units R-63 Multifamily Urban Zoning 1912 Construction PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 PROPERTY SUMMARY 4 PHOTOS 7 PROPERTY SURVEY R-63 MULTIFAMILY 8 FLOOR PLANS URBAN ZONING 11 SALES COMPARABLES 12 RICHMOND’S FAN DISTRICT 13 DEMOGRAPHICS & MARKET DATA 7,500 SF 14 MULTIFAMILY MARKET ANALYSIS PARCEL AREA 15 LOCATION MAP 16 ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL TEAM 13,095 SF BUILDING AREA 3,273 SF BASEMENT Communication: One South Commercial is the exclusive representative of Seller in its disposition of 2700 Idlewood Ave. All communications regarding the property should be directed to the One South Commercial listing team. 24 RESIDENTIAL Property Tours: UNITS Prospective purchasers should contact the listing team regarding property tours. Please provide at least 72 hours advance notice when requesting a tour date out of consideration for current residents. Offers: Offers should be submitted via email to the listing team in the form of a non- binding letter of intent and should include: 1) Purchase Price; 2) Earnest Money Deposit; 3) Due Diligence and Closing Periods. 1912 HISTORIC Disclaimer: CONSTRUCTION This offering memorandum is intended as a reference for prospective purchasers in the evaluation of the property and its suitability for investment. Neither One South Commercial nor Seller make any representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the materials contained in the offering memorandum. -

Reynolds Building Overall View Rear View

NORTH CAROLINA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE Office of Archives and History Department of Cultural Resources NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Reynolds Building Winston-Salem, Forsyth County, FY2141, Listed 8/19/2014 Nomination by Jen Hembree Photographs by Jen Hembree, November 2013 and March 2014 Overall view Rear view NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Reynolds Building Other names/site number: R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Office Building Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: 51 E. Fourth Street City or town: Winston-Salem State: NC County: Forsyth Not For Publication:N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Richmond: Evolution of a City As Shown Through Maps at the Library of Virginia

RICHMOND: EVOLUTION OF A CITY AS SHOWN THROUGH MAPS AT THE LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA The City of Richmond evolved from a trading post at Shockoe Creek to become Virginia’s capital city. In 1737 William Mayo, a friend of William Byrd II, completed his survey of the town of Richmond. His plan was one common to the Tidewater, a rectangular town design located east of Shockoe Creek. That year, Byrd held a lottery to sell off town lots. Mayo’s original plan included 112 numbered lots, 14 lots designated by letters, and two without any identification. Lots 97 and 98 were set aside for the Henrico Parish vestry, and St. John’s Church was erected on them in 1741. In 1742 Virginia’s General Assembly granted Richmond a town charter. Byrd’s son, William Byrd III, in debt and seeking a way to pay off his creditors, decided to hold a lottery in 1768 to sell additional lots west of Shockoe Creek. When Virginia’s capital moved from Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780, Shockoe Hill was chosen as the site for the new capitol building; it would look over the town of Richmond that had developed on flat land adjacent to the James River. Nine directors, one of whom was Thomas Jefferson, were appointed to plan Virginia’s new capital. Jefferson proposed a gridiron plan for Shockoe Hill that would set apart the platted portion of “Richmond Town” from the new capitol. There would be two major connecting streets, Main and Cary, and “Capitol Square” would consist of three buildings. -

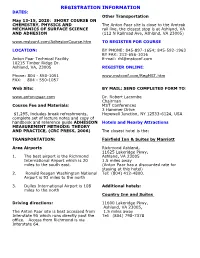

Hotel, Travel and Registration Information

REGISTRATION INFORMATION DATES: Other Transportation May 13-15, 2020: SHORT COURSE ON CHEMISTRY, PHYSICS AND The Anton Paar site is close to the Amtrak MECHANICS OF SURFACE SCIENCE rail line, the closest stop is at Ashland, VA AND ADHESION (112 N Railroad Ave, Ashland, VA 23005) www.mstconf.com/AdhesionCourse.htm TO REGISTER FOR COURSE LOCATION: BY PHONE: 845-897-1654; 845-592-1963 BY FAX: 212-656-1016 Anton Paar Technical Facility E-mail: [email protected] 10215 Timber Ridge Dr. Ashland, VA, 23005 REGISTER ONLINE: Phone: 804 - 550-1051 www.mstconf.com/RegMST.htm FAX: 804 - 550-1057 Web Site: BY MAIL: SEND COMPLETED FORM TO: www.anton-paar.com Dr. Robert Lacombe Chairman Course Fee and Materials: MST Conferences 3 Hammer Drive $1,295, includes break refreshments, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533-6124, USA complete set of lecture notes and copy of handbook and reference guide ADHESION Hotels and Nearby Attractions MEASUREMENT METHODS: THEORY AND PRACTICE, (CRC PRESS, 2006) The closest hotel is the: TRANSPORTATION: Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott Area Airports Richmond Ashland, 11625 Lakeridge Pkwy, 1. The best airport is the Richmond Ashland, VA 23005 International Airport which is 20 1.5 miles away miles to the south east. (Anton Paar has a discounted rate for staying at this hotel) 2. Ronald Reagan Washington National Tel: (804) 412-4800. Airport is 93 miles to the north 3. Dulles International Airport is 108 Additional hotels: miles to the north Country Inn and Suites Driving directions: 11600 Lakeridge Pkwy, Ashland, VA 23005, The Anton Paar site is best accessed from 1.5 miles away Interstate 95 which runs directly past the Tel: (804) 798-7378 office. -

Downtown Richmond, Virginia

Hebrew Cemetery HOSPITAL ST. Shockoe Cemetery Downtown Richmond, Virginia Visitor Center Walking Tour Richmond Liberty Trail Interpretive Walk Parking Segway Tour Richmond Slave Trail Multiuse Trail Sixth Mt. Zion Baptist Church Park Water Attraction James River Flood Wall National Donor J. Sargeant Reynolds Memorial Community College Maggie Walker Downtown Campus National Bill “Bojangles” Oliver Hill Greater Robinson Statue Historic Site Bust Richmond Richmond Convention Coliseum Abner Center Clay Park Hippodrome Theater Museum and Valentine White House of John Richmond the Confederacy Jefferson RICHMOND REGION Abady Marshall History Center Park VISITOR CENTER House Festival VCU Medical Center Patrick Park and MCV Campus Richmond’s Henry Park City First African African Burial Stuart C. Virginia Repertory The National Hall Old City Monumental Siegel Center Sara Belle and Theater Hall Church Baptist Church Ground Neil November St. John’s Theatre Libraryof Virginia Church Richmond Virginia Civil Rights Lumpkin’s Jail Elegba Center Stage George Monument Washington River Chimborazo Folklore . Winfree Cottage T Monument S Medical Museum Society City Segs H Executive T 2 Bell Virginia Mansion 1 Tower Beth Ahabah Capitol Old Museum & St. Paul’s 17th Street Episcopal First Fellows Edgar Allan Archives Freedom Reconciliation Hall Farmers’ Market Soldiers & Sailers VCU Monroe Richmond Bolling Church Statue Poe Museum Monument Park Campus Monroe Center Public Library Haxall Main Street Cathedral of the Park House Auction Station Virginia W.E. Singleton -

- Sj Clty OH TOWN:

Form 10-300 UNiTLll STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR iJul* 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM ENTRY NUMBER DATC (Typo all enfries - complete applicable sections) ~ .- ---EIAYMONT AND. OC HISTORIC: E1AY - .-- . - .- -. -..MONT. STREET AN,:, NLI~IIRER~ Ha9ton Street or Spottswood Road ClTI OR TOWN: C *.> L, E (in cit.) 760 Public Acquksiti~n: ZJ Occupied In Process Q Unoccupisd Ci Object I17 Both 0 Being Considered 0 Prsssrrotion ~ork in progrs.. 2 Agrlrvlturul 11 ;i Govsrnmant Ej Pork Tronsportotion Comments !i .. Commmrclo; :! Industrial Privots R.sidence ;.~1 0Other (SP~CI~J i + 1 [~-1 Eduro~ion~l i-1 Mititory Religious 1 i) E-~~~IO;,,~,.~~rid Museum Scientific i - -.-- ! -. - I (:XI% o Kiclimond, Department of Recreation and Parks / ~ W r- -~ - ~. -- lSTLIi, INI. NUMBER: ., W '1'1, >Io;.rii!c, Laurel Street !- STATE: VIRGINIA - -- City Hall - -- STREET AN<NUMBER: , -. .,... -4 '?c~~thand Broad Streets - . .- ;- sj ClTY OH TOWN: :. -. COOK ,? ,j ; Ri cI~II~<,~IcI - VIRGINIA 51 ' EXISTING SURVEYS . -~ liill~L,', 511UV1 . ,:$! : .) !li.otoric Iandmrks C~nmission-. Survey DIT~ i.1 ;LJ>, .,) *. 1971 0 Fader01 Stota 0 County 0 Local DEPDrl iR> i iH SUPVEI RECORDS: l.i.: is Historir Landmarks Commission- csrnrt ni,rz~~s;~: 9t1, S;Lrc!et State Office Buildine. Room 1116 1CITY 01< rOVi'i STATE: Richrnnil~, 1 . ..- Virginia Sicx. f,.oN.- ~ ~ . .. .~~ - - ~ --.-----.-.-....u-.,. - I (Check One) I C1 Exc.ll*nt Good 0 F.8, [IJ Ostsrior-ted 0 Rvnns 13 Unexposed (Check on~) (Check on.,, 0 Altered 1% Una11~r.d Cl Moved Onglnol Sate DESCRlQE THE PRESENT AND ORlGlNIL (11 known) WHISICAL APPEIRANCE MAYMON T The eclectic mansion at Maymont, designed in 1890 by Edgerton S. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. VLR Listed: 4/17/2019 NRHP Listed: 5/3/2019 1. Name of Property Historic name: Manchester Trucking and Commercial Historic District Other names/site number: VDHR File #127-6519 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Primarily along Commerce Road, Gordon Ave., and Dinwiddie Ave City or town: Richmond State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic -

406 W Broad St Richmond, Va 23220

ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL FOR LEASE | 4,000 SF W BROAD ST COMMERCIAL SPACE 406 W BROAD ST RICHMOND, VA 23220 $3,500/Month/Modified Gross PID: N0000206019 4,000+/- SF TOTAL 1,636+/- SF Street Level Retail 2,364+/- SF Lower Level Office/Storage 2 Off-Street Parking Spaces B-4 Central Business Zoning PETERSBURG[1] MULTIFAMILY PORTFOLIO Downtown Commercial Space on W Broad St This 4,000+/- SF commercial space is available for immediate lease. Located on this busy stretch of W Broad St in Richmond’s Downtown Arts District, this listing features 1,636+/- SF of street level space. Large storefront windows, exposed brick, and hardwood flooring are highlights of the interior that was completely renovated in 2010. In addition, 2,364+/- SF is available on the lower level for offices or storage. The B-4 Central Business zoning allows for a wide variety of commercial uses including retail, restaurant, office, personal service, and many others, and makes this location ideal for a new Downtown business. ADDRESS | 406 W Broad St STREET LEVEL 1,636+/- SF COMMERCIAL FIRST LEVEL PID | N0000206019 ZONING | B-4 Central Business LEASABLE AREA | 4,000 +/- SF STREET LEVEL | 1,636 +/- SF PRICE | $3,500/Mo/Modified Gross 2,364+/- SF B-4 CENTRAL PARKING | 2 Spaces Off-Street LOWER LEVEL BUSINESS ZONING *Information provided deemed reliable but not guaranteed 406 W BROAD ST | RICHMOND VA 406 W BROAD ST | RICHMOND VA DOWNTOWN ARTS DISTRICT N BELVIDERE ST JACKSON WARD FAN DISTRICT 406 W BROAD ST MONROE PARK N ADAMS ST VCU MONROE CAMPUS RICHMOND CONVENTION CTR THE JEFFERSON BROAD STREET MONROE WARD RANDOLPH MAIN STREET VCU MED CENTER CARY STREET OREGON HILL CAPITOL SQUARE HOLLYWOOD CEMETERY UNION HILL DOWNTOWN RICHMOND CHURCH HILL ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL CONTACT CLINT GREENE [email protected] 804.873.9501 1821 E MAIN STREET | RICHMOND VA ONE SOUTH COMMERCIAL 2314 West Main Street | Richmond VA 23220 | onesouthcommercial.com | 804.353.0009 . -

Richmond: Mooreland Farms 175

174 Richmond: Mooreland Farms 175 RICHMOND: Friday, April 27, 2018 Westmoreland10 a.m. to 4.30 p.m. The Boxwood Garden Club Place Thanks Photo courtesy of Ashley Farley Rachel Davis and Built around World War I, this neighborhood offers close proximity to downtown and some of the city’s earliest and most intriguing architecturally-designed houses. From Helen Nunley classic 17th century English style Georgian homes to Mediterranean-inspired villas, Westmoreland Place has the look and feel of Old World Europe. Beginning in 1915 2018 Historic Garden there was a demand for residential construction that drove developers west. Showcasing Week Chairs work by renowned architectural firms such as Noland & Baskervill, these homes blend grand-scaled landscape with stately architecture. The Executive Mansion, the oldest governor’s mansion in the U.S. built and still used as a home, is also open for tour and is a short drive east of the tour area. Tuckahoe Plantation Hosted by The Boxwood Garden Club The Tuckahoe Garden Club of Westhampton Sneed’s Nursery & Garden Center, Strange’s Florist Greenhouse & Garden Center Short Three Chopt Garden Club Pump and Mechanicsville, Tweed, Williams The James River Garden Club & Sherrill and Gather. Chairmen Combo Ticket for three-day pass: $120 pp. available online only at www.vagarden- Rachel Davis and Helen Nunley week.org. Allows access to all three days of [email protected] Richmond touring - Wednesday, Thursday and Friday - featuring 19 properties in total. Tickets: $50 pp. $20 single-site. Tickets available on tour day at tour headquarters Group Tour Information: 20 or more people and at ticket table at 4703 Pocahontas Ave.