First Aid for Hazardous Marine Life Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

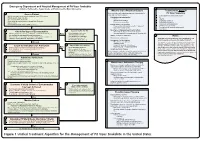

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Spider Bites

Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Office of Public Health, Louisiana Dept of Health & Hospitals 800-256-2748 (24 hr number) www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov SPIDER BITES Revised 6/13/2007 Epidemiology There are over 3,000 species of spiders native to the United States. Due to fragility or inadequate length of fangs, only a limited number of species are capable of inflicting noticeable wounds on human beings, although several small species of spiders are able to bite humans, but with little or no demonstrable effect. The final determination of etiology of 80% of suspected spider bites in the U.S. is, in fact, an alternate diagnosis. Therefore the perceived risk of spider bites far exceeds actual risk. Tick bites, chemical burns, lesions from poison ivy or oak, cutaneous anthrax, diabetic ulcer, erythema migrans from Lyme disease, erythema from Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, sporotrichosis, Staphylococcus infections, Stephens Johnson syndrome, syphilitic chancre, thromboembolic effects of Leishmaniasis, toxic epidermal necrolyis, shingles, early chicken pox lesions, bites from other arthropods and idiopathic dermal necrosis have all been misdiagnosed as spider bites. Almost all bites from spiders are inflicted by the spider in self defense, when a human inadvertently upsets or invades the spider’s space. Of spiders in the United States capable of biting, only a few are considered dangerous to human beings. Bites from the following species of spiders can result in serious sequelae: Louisiana Office of Public Health – Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Page 1 of 14 The Brown Recluse: Loxosceles reclusa Photo Courtesy of the Texas Department of State Health Services The most common species associated with medically important spider bites: • Physical characteristics o Length: Approximately 1 inch o Appearance: A violin shaped mark can be visualized on the dorsum (top). -

Development of a Quantitative PCR Assay for the Detection And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/544247; this version posted February 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Development of a quantitative PCR assay for the detection and enumeration of a potentially ciguatoxin-producing dinoflagellate, Gambierdiscus lapillus (Gonyaulacales, Dinophyceae). Key words:Ciguatera fish poisoning, Gambierdiscus lapillus, Quantitative PCR assay, Great Barrier Reef Kretzschmar, A.L.1,2, Verma, A.1, Kohli, G.S.1,3, Murray, S.A.1 1Climate Change Cluster (C3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia 2ithree institute (i3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia, [email protected] 3Alfred Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum fr Polar- und Meeresforschung, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570, Bremerhaven, Germany Abstract Ciguatera fish poisoning is an illness contracted through the ingestion of seafood containing ciguatoxins. It is prevalent in tropical regions worldwide, including in Australia. Ciguatoxins are produced by some species of Gambierdiscus. Therefore, screening of Gambierdiscus species identification through quantitative PCR (qPCR), along with the determination of species toxicity, can be useful in monitoring potential ciguatera risk in these regions. In Australia, the identity, distribution and abundance of ciguatoxin producing Gambierdiscus spp. is largely unknown. In this study we developed a rapid qPCR assay to quantify the presence and abundance of Gambierdiscus lapillus, a likely ciguatoxic species. We assessed the specificity and efficiency of the qPCR assay. The assay was tested on 25 environmental samples from the Heron Island reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef, a ciguatera endemic region, in triplicate to determine the presence and patchiness of these species across samples from Chnoospora sp., Padina sp. -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

ALLERGIC REACTIONS/ANAPHYLAXIS Connie J

Northwest Community EMS System Paramedic Education Program ALLERGIC REACTIONS/ANAPHYLAXIS Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P Reading assignments Text-Vol.1 pp. 235, 1272-1276 SOP: Allergic Reactions/ Anaphylactic Shock Assumed knowledge: Drugs: Epinephrine 1:1,000, 1:10,000; albuterol, ipratropium, dopamine, glucagon KNOWLEDGE OBJECTIVES Upon reading the assigned text assignments and completion of the class and homework questions, each participant will independently do the following with at least an 80% degree of accuracy and no critical errors: 1. Define allergic reaction. 2. Describe the incidence, morbidity and mortality of allergic reactions and anaphylaxis. 3. Identify risk factors that predispose a patient to anaphylaxis. 4. Explain the physiology of the immune system following exposure to an allergen including activation of histamine receptors and the formation of antibodies. 5. Discuss the pathophysiology of allergic reactions and anaphylaxis. 6. Describe the common modes by which allergens enter the body. 7. Compare and contrast natural and acquired and active vs. passive immunity. 8. Identify antigens most frequently associated with anaphylaxis. 9. Differentiate the clinical presentation and severity of risk for a mild, moderate and severe allergic reaction with an emphasis on recognizing an anaphylactic reaction. 10. Integrate the pathophysiologic principles of anaphylaxis with treatment priorities. 11. Sequence care per SOP for patients with mild, moderate and severe allergic reactions. CJM: S14 NWC EMSS Paramedic Education Program ALLERGIC REACTIONS/ANAPHYLAXIS Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P I. Immune system A. Principal body system involved in allergic reactions. Others include the cutaneous, cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, and gastrointestinal systems. -

Ciguatera: Current Concepts

Ciguatera: Current concepts DAVID Z. LEVINE, DO Ciguatera poisoning develops unraveling the diagnosis may prove difficult. after ingestion of certain coral reef-asso Although the syndrome has been known for at ciated fish. With travel to and from the least hundreds of years, its mechanisms are tropics and importation of tropical food only beginning to be elucidated. Effective treat fish increasing, ciguatera has begun to ments have just begun to emerge. appear in temperate countries with more Ciguatera is a major public health prob frequency. The causative agents are cer lem in the tropics, with probably more than tain varieties of the protozoan dinofla 30,000 poisonings yearly in Puerto Rico and gellate Gambierdiscus toxicus, but bacte the US Virgin Islands alone. The endemic area ria associated with these protozoa may is bounded by latitudes 37° north and south. have a role in toxin elaboration. A specif Ciguatera in temperate countries is a concern ic "ciguatoxin" seems to cause the symptoms, because people returning from business trips, but toxicosis may also be a result of a fam vacations, or living in the tropics may have ily of toxins. Toxicosis develops from 10 been poisoned through food they had eaten. minutes to 30 hours after ingestion of poi The development of worldwide marketing of soned fish, and the syndrome can include fish from a variety of ecosystems creates a dan gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, ger of ciguatera intoxication in climates far as well as chills, sweating, pruritus, brady removed from sandy beaches and waving·palms. cardia, tachycardia, and long-lasting weak Outbreaks have been reported in Vermont, ness and fatigue. -

Arthropod Envenomations: Immunologic and Toxicologic Considerations Cyrus Rangan, MD, FAAP, ACMT

Emergency Department Evaluation and Treatment for Children With Arthropod Envenomations: Immunologic and Toxicologic Considerations Cyrus Rangan, MD, FAAP, ACMT Arthropod envenomations are a significant cause of environmental injury in children. Bees, wasps, and spiders inflict injury via specialized venoms with a broad range of components, mechanisms, and potential treatments. Immunologic and toxicologic considerations in the evaluation and management of arthropod envenomations are important for the under- standing of the progression of envenomations, prompt diagnosis of severe conditions including anaphylaxis, and the use of antivenom in selected cases. Clin Ped Emerg Med 8:104-109 ª 2007 Published by Elsevier Inc. KEYWORDS envenomation, arthropod, arachnida, hymenoptera rthropod bites and stings accounted for more than ever, clinical symptoms of envenomation and treatment A75000 reports to poison control centers in the are similar. Bees are attracted to carbon dioxide (hence, United States in 2005 [1]. The phylum Arthropoda the predilection for bees to fly around the facial area), includes 2 clinically important classes: Insecta (order: bright colors (ie, clothing), and sweet odors (ie, Hymenoptera—bees, wasps, yellow jackets, and ants), perfumes, fragrances). Children commonly believe that and Arachnida (ticks, scorpions, and spiders). Virtually bees are aggressive insects, but they are mostly docile all arthropods possess some form of venom for immobi- creatures; indeed, the sometimes fearful behavior of lization and digestion of prey, yet only a select few species children around a nearby bee may increase the risk of a have developed venom delivery mechanisms capable of sting. Mass envenomations may occur when a hive is poisoning humans [2]. Pathophysiologic mechanisms of physically disturbed by children throwing rocks or other venom vary considerably among arthropods, and clinical objects at the hive [3]. -

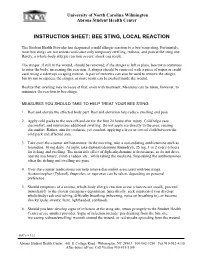

Instruction Sheet: Bee Sting, Local Reaction

University of North Carolina Wilmington Abrons Student Health Center INSTRUCTION SHEET: BEE STING, LOCAL REACTION The Student Health Provider has diagnosed a mild allergic reaction to a bee/wasp sting. Fortunately, most bee stings are not serious and cause only temporary swelling, redness, and pain at the sting site. Rarely, a whole-body allergic reaction occurs; shock can result. The stinger, if still in the wound, should be removed; if the stinger is left in place, bee toxin continues to enter the body, increasing the reaction. A stinger should be removed with a piece of paper or credit card, using a sideways scraping motion. A pair of tweezers can also be used to remove the stinger, but try not to squeeze the stinger, or more toxin can be pushed inside the wound. Realize that swelling may increase at first, even with treatment. Measures can be taken, however, to minimize the reaction to bee stings. MEASURES YOU SHOULD TAKE TO HELP TREAT YOUR BEE STING: 1. Rest and elevate the affected body part. Rest and elevation help reduce swelling and pain. 2. Apply cold packs to the area off-and-on for the first 24 hours after injury. Cold helps ease discomfort, and minimizes additional swelling. Do not apply ice directly to the area, causing discomfort. Rather, aim for coolness, yet comfort, applying a layer or two of cloth between the cold pack and affected area. 3. Take over-the-counter antihistamines: In the morning, take a non-sedating antihistamine such as loratadine, 10 mg daily. At night, take diphenhydramine (Benadryl), 25 mg, 1 or 2 every 6 hours for itching and swelling. -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

![Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0546/bites-and-stings-poisonous-animals-and-plants-720546.webp)

Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]

Poisonous animals and plants Dr Tim Healing Dip.Clin.Micro, DMCC, CBIOL, FZS, FRSB Course Director, Course in Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London Faculty of Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Animal and plant toxins • In most instances the numbers of people affected will be small • There are a few instances where larger numbers may be involved – mainly due to food-borne toxins Poisonous species (N.B. Venomous species use poisons for attack, poisonous animals and plants for passive defence) Venomous and poisonous animals – Reptiles (snakes) – Amphibians (dart frogs) – Arthropods (scorpions, spiders, wasps, bees, centipedes) – Aquatic animals (fish, jellyfish, octopi) Poisonous plants – Contact stinging (nettles, poison ivy, algae) – Poisonous by ingestion (fungi, berries of some plants) – Some algae Snakes Venomous Snakes • About 600 species of snake are venomous (ca. 25% of all snake species). Four main groups: – Elapidae (elapids). Mambas, Cobras, King cobras, Kraits, Taipans, Sea snakes, Brown snakes, Coral snakes. – Viperidae (viperids). True vipers and pit vipers (including Rattlesnakes, Copperheads and Cottonmouths) – Colubridae (colubrids). Mostly harmless, but includes the Boomslang – Atractaspididae (atractaspidids). Burrowing asps, Mole vipers, Stiletto snakes. Geographical distribution • Elapidae: – On land, worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, except in Europe. – Sea snakes occur in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific • Viperidae: – The Americas, Africa and Eurasia. • Boomslangs -

Venom Week 2012 4Th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous

17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins & Venom Week 2012 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012 1 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction 01 Scientific Organizing Committee 02 Local Organizing Committee / Sponsors / Co-Chairs 02 Welcome Messages 04 Governor’s Proclamation 08 Meeting Program 10 Sunday 13 Monday 15 Tuesday 20 Wednesday 26 Thursday 30 Friday 36 Poster Session I 41 Poster Session II 47 Supplemental program material 54 Additional Abstracts (#298 – #344) 61 International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis 99 2 Introduction Welcome to the 17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology (IST), held jointly with Venom Week 2012, 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous, in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012. This is a supplement to the special issue of Toxicon. It contains the abstracts that were submitted too late for inclusion there, as well as a complete program agenda of the meeting, as well as other materials. At the time of this printing, we had 344 scientific abstracts scheduled for presentation and over 300 attendees from all over the planet. The World Congress of IST is held every three years, most recently in Recife, Brazil in March 2009. The IST World Congress is the primary international meeting bringing together scientists and physicians from around the world to discuss the most recent advances in the structure and function of natural toxins occurring in venomous animals, plants, or microorganisms, in medical, public health, and policy approaches to prevent or treat envenomations, and in the development of new toxin-derived drugs. -

Prioritization of Health Services

PRIORITIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES A Report to the Governor and the 74th Oregon Legislative Assembly Oregon Health Services Commission Office for Oregon Health Policy and Research Department of Administrative Services 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures . iii Health Services Commission and Staff . .v Acknowledgments . .vii Executive Summary . ix CHAPTER ONE: A HISTORY OF HEALTH SERVICES PRIORITIZATION UNDER THE OREGON HEALTH PLAN Enabling Legislatiion . 3 Early Prioritization Efforts . 3 Gaining Waiver Approval . 5 Impact . 6 CHAPTER TWO: PRIORITIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES FOR 2008-09 Charge to the Health Services Commission . .. 25 Biennial Review of the Prioritized List . 26 A New Prioritization Methodology . 26 Public Input . 36 Next Steps . 36 Interim Modifications to the Prioritized List . 37 Technical Changes . 38 Advancements in Medical Technology . .42 CHAPTER THREE: CLARIFICATIONS TO THE PRIORITIZED LIST OF HEALTH SERVICES Practice Guidelines . 47 Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) . 47 Chronic Anal Fissure . 48 Comfort Care . 48 Complicated Hernias . 49 Diagnostic Services Not Appearing on the Prioritized List . 49 Non-Prenatal Genetic Testing . 49 Tuberculosis Blood Test . 51 Early Childhood Mental Health . 52 Adjustment Reactions In Early Childhood . 52 Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders in Early Childhood . 53 Disruptive Behavior Disorders In Early Childhood . 54 Mental Health Problems In Early Childhood Related To Neglect Or Abuse . 54 Mood Disorders in Early Childhood . 55 Erythropoietin . 55 Mastocytosis . 56 Obesity . 56 Bariatric Surgery . 56 Non-Surgical Management of Obesity . 58 PET Scans . 58 Prenatal Screening for Down Syndrome . 59 Prophylactic Breast Removal . 59 Psoriasis . 59 Reabilitative Therapies . 60 i TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont’d) CHAPTER THREE: CLARIFICATIONS TO THE PRIORITIZED LIST OF HEALTH SERVICES (CONT’D) Practice Guidelines (Cont’d) Sinus Surgery .