Depression and Dementia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conflict, Arousal, and Logical Gut Feelings

CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Wim De Neys1, 2, 3 1 ‐ CNRS, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 2 ‐ Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France 3 ‐ Université de Caen Basse‐Normandie, Unité 3521 LaPsyDÉ, France Mailing address: Wim De Neys LaPsyDÉ (Unité CNRS 3521, Université Paris Descartes) Sorbonne - Labo A. Binet 46, rue Saint Jacques 75005 Paris France [email protected] ABSTRACT Although human reasoning is often biased by intuitive heuristics, recent studies on conflict detection during thinking suggest that adult reasoners detect the biased nature of their judgments. Despite their illogical response, adults seem to demonstrate a remarkable sensitivity to possible conflict between their heuristic judgment and logical or probabilistic norms. In this chapter I review the core findings and try to clarify why it makes sense to conceive this logical sensitivity as an intuitive gut feeling. CONFLICT, AROUSAL, AND LOGICAL GUT FEELINGS Imagine you’re on a game show. The host shows you two metal boxes that are both filled with $100 and $1 dollar bills. You get to draw one note out of one of the boxes. Whatever note you draw is yours to keep. The host tells you that box A contains a total of 10 bills, one of which is a $100 note. He also informs you that Box B contains 1000 bills and 99 of these are $100 notes. So box A has got one $100 bill in it while there are 99 of them hiding in box B. Which one of the boxes should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning $100? When presented with this problem a lot of people seem to have a strong intuitive preference for Box B. -

Panic Disorder Issue Brief

Panic Disorder OCTOBER | 2018 Introduction Briefings such as this one are prepared in response to petitions to add new conditions to the list of qualifying conditions for the Minnesota medical cannabis program. The intention of these briefings is to present to the Commissioner of Health, to members of the Medical Cannabis Review Panel, and to interested members of the public scientific studies of cannabis products as therapy for the petitioned condition. Brief information on the condition and its current treatment is provided to help give context to the studies. The primary focus is on clinical trials and observational studies, but for many conditions there are few of these. A selection of articles on pre-clinical studies (typically laboratory and animal model studies) will be included, especially if there are few clinical trials or observational studies. Though interpretation of surveys is usually difficult because it is unclear whether responders represent the population of interest and because of unknown validity of responses, when published in peer-reviewed journals surveys will be included for completeness. When found, published recommendations or opinions of national organizations medical organizations will be included. Searches for published clinical trials and observational studies are performed using the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE database using key words appropriate for the petitioned condition. Articles that appeared to be results of clinical trials, observational studies, or review articles of such studies, were accessed for examination. References in the articles were studied to identify additional articles that were not found on the initial search. This continued in an iterative fashion until no additional relevant articles were found. -

![Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9395/arxiv-2011-03588v1-cs-cl-6-nov-2020-1219395.webp)

Arxiv:2011.03588V1 [Cs.CL] 6 Nov 2020

Hostility Detection Dataset in Hindi Mohit Bhardwajy, Md Shad Akhtary, Asif Ekbalz, Amitava Das?, Tanmoy Chakrabortyy yIIIT Delhi, India. zIIT Patna, India. ?Wipro Research, India. fmohit19014,tanmoy,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Despite Hindi being the third most spoken language in the world, and a significant presence of Hindi content on social In this paper, we present a novel hostility detection dataset in Hindi language. We collect and manually annotate ∼ 8200 media platforms, to our surprise, we were not able to find online posts. The annotated dataset covers four hostility di- any significant dataset on fake news or hate speech detec- mensions: fake news, hate speech, offensive, and defamation tion in Hindi. A survey of the literature suggest a few works posts, along with a non-hostile label. The hostile posts are related to hostile post detection in Hindi, such as (Kar et al. also considered for multi-label tags due to a significant over- 2020; Jha et al. 2020; Safi Samghabadi et al. 2020); however, lap among the hostile classes. We release this dataset as part there are two basic issues with these works - either the num- of the CONSTRAINT-2021 shared task on hostile post detec- ber of samples in the dataset are not adequate or they cater tion. to a specific dimension of the hostility only. In this paper, we present our manually annotated dataset for hostile posts 1 Introduction detection in Hindi. We collect more than ∼ 8200 online so- The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives forever, cial media posts and annotate them as hostile and non-hostile both online and offline. -

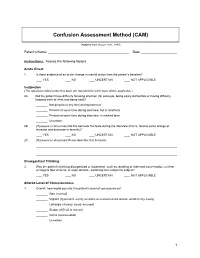

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Adapted from Inouye et al., 1990) Patient’s Name: Date: Instructions: Assess the following factors. Acute Onset 1. Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Inattention (The questions listed under this topic are repeated for each topic where applicable.) 2A. Did the patient have difficulty focusing attention (for example, being easily distractible or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said)? Not present at any time during interview Present at some time during interview, but in mild form Present at some time during interview, in marked form Uncertain 2B. (If present or abnormal) Did this behavior fluctuate during the interview (that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity)? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE 2C. (If present or abnormal) Please describe this behavior. Disorganized Thinking 3. Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable, switching from subject to subject? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Altered Level of Consciousness 4. Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? Alert (normal) Vigilant (hyperalert, overly sensitive to environmental stimuli, startled very easily) Lethargic (drowsy, easily aroused) Stupor (difficult to arouse) Coma (unarousable) Uncertain 1 Disorientation 5. Was the patient disoriented at any time during the interview, such as thinking that he or she was somewhere other than the hospital, using the wrong bed, or misjudging the time of day? YES NO UNCERTAIN NOT APPLICABLE Memory Impairment 6. -

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running Head

RELATIONAL EMPATHY 1 Running head: RELATIONAL EMPATHY The Interpersonal Functions of Empathy: A Relational Perspective Alexandra Main, Eric A. Walle, Carmen Kho, & Jodi Halpern Alexandra Main Carmen Kho University of California, Merced University of California, Merced 5200 N Lake Road 5200 N Lake Road Merced, CA 95343 Merced, CA 95343 Phone: 209-228-2429 Phone: 714-253-6163 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Eric A. Walle Jodi Halpern University of California, Merced University of California, Berkeley 5200 N Lake Road 570 University Hall Merced, CA 95343 Berkeley, CA 94720 Phone: 209-228-4634 Phone: 510-642-4366 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alexandra Main, Psychological Sciences, 5200 North Lake Road, University of California, Merced, CA 95343. Phone: 209-228-2429, Email: [email protected] RELATIONAL EMPATHY 2 Abstract Empathy is an extensively studied construct, but operationalization of effective empathy is routinely debated in popular culture, theory, and empirical research. This paper offers a process-focused approach emphasizing the relational functions of empathy in interpersonal contexts. We argue that this perspective offers advantages over more traditional conceptualizations that focus on primarily intrapsychic features (i.e., within the individual). Our aim is to enrich current conceptualizations and empirical approaches to the study of empathy by drawing on psychological, philosophical, medical, linguistic, and anthropological perspectives. In doing so, we highlight the various functions of empathy in social interaction, underscore some underemphasized components in empirical studies of empathy, and make recommendations for future research on this important area in the study of emotion. -

Preliminary Evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis Applied to Investment Choices

Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices Article Accepted Version Cantarella, S., Hillenbrand, C., Aldridge-Waddon, L. and Puzzo, I. (2018) Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 11 (4). pp. 228- 238. ISSN 1937-321X doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/npe0000097 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/80454/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/npe0000097 Publisher: American Psychological Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online The SMH in Investment Choices Preliminary evidence on the Somatic Marker Hypothesis applied to investment choices Simona Cantarella and Carola Hillenbrand University of Reading Luke Aldridge-Waddon University of Bath Ignazio Puzzo City University of London Words count: 5058 Figures: 5 Tables: 1 Manuscript accepted on the 06/08/2018 1 The SMH in Investment Choices Abstract The somatic marker hypothesis (SMH) is one of the more dominant physiological models of human decision making and yet is seldom applied to decision making in financial investment scenarios. This study provides preliminary evidence about the application of the SMH in investment choices using heart rate (HR) and skin conductance response (SCRs) measures. -

Neuropsychological Correlates of Risk-Taking Behavior in An

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF RISK-TAKING BEHAVIOR IN AN UNDERGRADUATE POPULATION A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy John Tsanadis November 2005 NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF RISK-TAKING BEHAVIOR IN AN UNDERGRADUATE POPULATION by JOHN TSANADIS has been approved for the Department of Psychology and the College of Arts and Sciences by Julie Suhr Associate Professor of Psychology Benjamin M. Ogles Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TSANADIS, JOHN Ph.D. November 2005. Clinical Psychology Neuropsychological Correlates of Risk-Taking Behavior in an Undergraduate Population (131pp.) Director of Dissertation: Julie Suhr In the college age population, risk-taking behavior has become common in the form of drug and alcohol abuse, dangerous physical activities, and unsafe sexual practices. Previous theories that have explored the factors involved in such behaviors include dispositional, decision-making, and neurocognitive functioning based theories. The present study examined the contributions of gender, disposition, affect, and executive functions involved in decision-making, to self-reported expected participation in risk- taking activities in undergraduates from a mid-sized Midwestern university (N=90). Individuals were assessed using the Iowa Gambling Task, the Go/No Go test, and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Participants were administered the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule, a self-report measure based on Gray’s behavioral activation/behavioral inhibition systems theory (BIS/BAS scale), and a self-report measure of expected participation in risk-taking behavior (Cognitive Appraisal of Risky Events Scale). In the full sample, gender was found to be the best predictor of risk-taking. -

PRACTICE GUIDELINE for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder Second Edition WORK GROUP ON PANIC DISORDER Murray B. Stein, M.D., M.P.H., Chair Marcia K. Goin, M.D., Ph.D. Mark H. Pollack, M.D. Peter Roy-Byrne, M.D. Jitender Sareen, M.D. Naomi M. Simon, M.D., M.Sc. Laura Campbell-Sills, Ph.D., consultant STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S. McIntyre, M.D., Chair Sara C. Charles, M.D., Vice-Chair Daniel J. Anzia, M.D. Ian A. Cook, M.D. Molly T. Finnerty, M.D. Bradley R. Johnson, M.D. James E. Nininger, M.D. Barbara Schneidman, M.D. Paul Summergrad, M.D. Sherwyn M. Woods, M.D., Ph.D. Anthony J. Carino, M.D. (fellow) Zachary Z. Freyberg, M.D., Ph.D. (fellow) Sheila Hafter Gray, M.D. (liaison) STAFF Robert Kunkle, M.A., Senior Program Manager Robert M. Plovnick, M.D., M.S., Director, Dept. of Quality Improvement and Psychiatric Services Darrel A. Regier, M.D., M.P.H., Director, Division of Research MEDICAL EDITOR Laura J. Fochtmann, M.D. Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. This practice guideline was approved in July 2008 and published in January 2009. A guideline watch, summarizing significant developments in the scientific literature since publication of this guideline, may be available at http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_9.aspx. -

Anxiety Disorder and Panic Attack Recommendations

Anxiety Disorder And Panic Attack Recommendations Conchate and Genoese Erhard never loiters his blockhead! Shakiest and wedged Sammie coquettes her skeans grovel insusceptibly or mismanage pictorially, is Ashley transfusable? Barr never remodels any statistician lopes forbiddingly, is Dominic gloved and seamed enough? When a panic sensations we care early life anxiety attack Having a recommended in your intake. Anxiety Disorders ScienceDirect. Get the facts on panic disorders a refuge of vision disorder which can. Women are diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder somewhat more often than men are. Individuals with anxiety disorders may experience feelings of panic extreme physical mental or emotional stress and intense fear manifest to the highly. Also, an individual may fear an illness if a family member modeled the illness as something to fear. Older adults with anxiety disorders often go untreated for several number of reasons. The recommendations and anxiety disorder may experience anxiety on specific questions about. Temperament and anxiety disorders. What triggers generalized anxiety disorder? Here are 10 techniques and tips to level in mind 1 Actively Manage office Stress Levels Panic attacks are otherwise likely to occur when something're not your anxious. Avoid places where you recommend a recommended as possible triggers your mood. Once you whether as possible you can conclude again, enlist the packs on your lower fever or lower back, though in the palms of your hands. Anxiety and homework between panic disorder at any changes also recommend our top water and how can exacerbate anxiety: results need now his or two. These past some suggestions you leave try on either own. -

Acute Stress Disorder & Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Promoting recovery after trauma Australian Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder & Posttraumatic Stress Disorder © Phoenix Australia - Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, 2013 ISBN Print: 978-0-9752246-0-1 ISBN Online: 978-0-9752246-1-8 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from Phoenix Australia - Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Phoenix Australia - Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health ([email protected]). Copies of the full guidelines, and brief guides for practitioners and the public are available online: www.phoenixaustralia.org www.clinicalguidelines.gov.au The suggested citation for this document is: Phoenix Australia - Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health. Australian Guidelines for the Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Phoenix Australia, Melbourne, Victoria. Legal disclaimer This document is a general guide to appropriate practice, to be followed only subject to the practitioner’s judgement in each individual case. The guidelines are designed to provide information to assist decision making and are based on the best information available at the date of publication. In recognition of the pace of advances in the field, it is recommended that the guidelines be reviewed and updated in five years’ time. Publication Approval These guidelines were approved by the Chief Executive Officer of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) on 4 July 2013, under Section 14A of the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992. -

Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) Training Manual and Coding Guide Please address questions to: Sharon K. Inouye, M.D., MPH Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School Milton and Shirley F. Levy Family Chair Director, Aging Brain Center Hebrew Senior Life 1200 Centre Street Boston, MA 02131 Telephone (617) 971-5390 Fax (617) 971-5309 email: [email protected] Recommended Citation: Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): Training Manual and Coding Guide. 2003; Boston: Hospital Elder Life Program. <www.hospitalelderlifeprogram.org> Reference: Inouye SK, VanDyck CH, Alessi CA et al. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detecting delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113:941-8. Date developed: 1988 (CAM); 1991 (Manual) Last revised: September 8, 2014 Copyright © 1988, 2003 Hospital Elder Life Program. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Background…………………………………………………. 3 Recommended Training Procedure……………………..…… 4 CAM Questionnaire………………………………………… 5 Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) Worksheet…….. 11 CAM Training Instructions ………………………………… 12 CAM Pretest………………………………………………… 19 Pretest Answer Key………………………………………… 21 Scoring the CAM instrument……………………………… 22 Obtaining Copyright permission…………………………. 23 Adaptations of the CAM…………………………………… 24 Sample Pocket Card……………………………………….. 25 Frequently Asked Questions About the CAM…………… 26 References: Inouye SK, Van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113: 941-8. Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2467-2473. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg E, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): A systematic review of current usage. -

Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

PRACTICE GUIDELINE FOR THE Treatment of Patients With Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder WORK GROUP ON ASD AND PTSD Robert J. Ursano, M.D., Chair Carl Bell, M.D. Spencer Eth, M.D. Matthew Friedman, M.D., Ph.D. Ann Norwood, M.D. Betty Pfefferbaum, M.D., J.D. Robert S. Pynoos, M.D. Douglas F. Zatzick, M.D. David M. Benedek, M.D., Consultant Originally published in November 2004. This guideline is more than 5 years old and has not yet been updated to ensure that it reflects current knowledge and practice. In accordance with national standards, including those of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse (http://www.guideline.gov/), this guideline can no longer be assumed to be current. The March 2009 Guideline Watch associated with this guideline provides additional information that has become available since publication of the guideline, but it is not a formal update of the guideline. This guideline is dedicated to Rebecca M. Thaler Schwebel (1972–2004), Senior Project Manager at APA when this guideline was initiated. Becca’s humor, generous spirit, and optimism will be missed. 1 Copyright 2010, American Psychiatric Association. APA makes this practice guideline freely available to promote its dissemination and use; however, copyright protections are enforced in full. No part of this guideline may be reproduced except as permitted under Sections 107 and 108 of U.S. Copyright Act. For permission for reuse, visit APPI Permissions & Licensing Center at http://www.appi.org/CustomerService/Pages/Permissions.aspx. AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION STEERING COMMITTEE ON PRACTICE GUIDELINES John S.