Development of a Novel Biofedelic Skull-Neck-Thorax Model Capable of Quantifying Motions of Aged Cervical Spine" (2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Sheet 1

MALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 8 7 8 OJ 7 .£l"00\.....• ;:; ::>0\~ <Il '"~IQ)I"->. ~cru::>s ~ 6 5 bladder penis prostate gland 4 scrotum seminal vesicle testicle urethra vas deferens FEMALE SEXUAL SYSTEM 2 1 8 " \ 5 ... - ... j 4 labia \ ""\ bladderFallopian"k. "'"f"";".'''¥'&.tube\'WIT / I cervixt r r' \ \ clitorisurethrauterus 7 \ ~~ ;~f4f~ ~:iJ 3 ovaryvagina / ~ 2 / \ \\"- 9 6 adapted from F.L.A.S.H. Reproductive System Reference Sheet 3: GLOSSARY Anus – The opening in the buttocks from which bowel movements come when a person goes to the bathroom. It is part of the digestive system; it gets rid of body wastes. Buttocks – The medical word for a person’s “bottom” or “rear end.” Cervix – The opening of the uterus into the vagina. Circumcision – An operation to remove the foreskin from the penis. Cowper’s Glands – Glands on either side of the urethra that make a discharge which lines the urethra when a man gets an erection, making it less acid-like to protect the sperm. Clitoris – The part of the female genitals that’s full of nerves and becomes erect. It has a glans and a shaft like the penis, but only its glans is on the out side of the body, and it’s much smaller. Discharge – Liquid. Urine and semen are kinds of discharge, but the word is usually used to describe either the normal wetness of the vagina or the abnormal wetness that may come from an infection in the penis or vagina. Duct – Tube, the fallopian tubes may be called oviducts, because they are the path for an ovum. -

Introduction Remove the Udder Removing the Pizzle (Penis)

fig . removing the udder, cut outwards through the skin fig 2. removing the pizzle Introduction This guide describes the carcass dressing procedures either side of the pizzle joining the cuts around the that are ideally carried out in a deer larder, after back of the scrotum. Continue the single central cut the gralloch has been performed in the field. The through the skin almost to the anus, taking care not Gralloch guide should be considered essential to damage the haunches. Pull the pizzle free where it companion reading. Both are linked to the Carcass runs over the pelvis, cutting the blood vessels. Use Inspection, Carcass Transport, Basic Hygiene, and the knife to free the pizzle where it turns forward Larder guides. inside the “V” of the pelvis. Leave outside the carcass (draped down the back if the carcass is suspended). Remove the udder It will be removed with the aitch bone, bladder, Fig 1. This is best done in the larder but a large udder remainder of the rectum and anus, later. can prevent access to the rear end and may have to be removed in the field before opening the stomach. Split the aitch bone Pinch the skin just in front of the udder and pulling Figs 3. and 4. Note that some venison processors on it all the time, cut around the udder, removing it would prefer that the aitch bone remains intact, whole, with the skin. Do not take the cut any further check before cutting. While causing the least possible rearwards until back in the larder. -

View of Urothelial and Metastatic Carcinoma Including Clinical Presentation, Diagnostic Testing, Treatment and Chiropractic Considerations Is Discussed

Daniels et al. Chiropractic & Manual Therapies (2016) 24:14 DOI 10.1186/s12998-016-0097-8 CASE REPORT Open Access Bladder metastasis presenting as neck, arm and thorax pain: a case report Clinton J. Daniels1,2,3*, Pamela J. Wakefield1,2 and Glenn A. Bub1,2 Abstract Background: A case of metastatic carcinoma secondary to urothelial carcinoma presenting as musculoskeletal pain is reported. A brief review of urothelial and metastatic carcinoma including clinical presentation, diagnostic testing, treatment and chiropractic considerations is discussed. Case presentation: This patient presented in November 2014 with progressive neck, thorax and upper extremity pain. Computed tomography revealed a destructive soft tissue mass in the cervical spine and additional lytic lesion of the 1st rib. Prompt referral was made for surgical consultation and medical management. Conclusion: Distant metastasis is rare, but can present as a musculoskeletal complaint. History of carcinoma should alert the treating chiropractic physician to potential for serious disease processes. Keywords: Chiropractic, Neck pain, Transitional cell carcinoma, Bladder cancer, Metastasis, Case report Background serious complication of UC is distant metastasis—with Urothelial carcinoma (UC), also known as transitional higher stage cancer and lymph involvement worsening cell carcinoma (TCC), accounts for more than 90 % of prognosis and cancer survival rate [10]. The 5-year all bladder cancers and commonly metastasizes to the cancer-specific survival rate of UC is estimated to be pelvic lymph nodes, lungs, liver, bones and adrenals or 78 % [10, 11]. brain [1, 2]. The spread of bladder cancer is mainly done Neck pain accounts for 24 % of all disorders seen by via the lymphatic system with the most frequent location chiropractors [12]. -

The Ear, Nose, and Throat Exam Jeffrey Texiera, MD and Joshua Jabaut, MD CPT, MC, USA LT, MC, USN

The Ear, Nose, and Throat Exam Jeffrey Texiera, MD and Joshua Jabaut, MD CPT, MC, USA LT, MC, USN Midatlantic Regional Occupational and Environmental Medicine Conference Sept. 23, 2017 Disclosures ●We have no funding or financial interest in any product featured in this presentation. The items included are for demonstration purposes only. ●We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Overview ● Overview of clinically oriented anatomy - presented in the format of the exam ● The approach ● The examination ● Variants of normal anatomy ● ENT emergencies ● Summary/highlights ● Questions Anatomy ● The head and neck exam consists of some of the most comprehensive and complicated anatomy in the human body. ● The ear, nose, and throat comprise a portion of that exam and a focused clinical encounter for an acute ENT complaint may require only this portion of the exam. Ears www.Medscape.com www.taqplayer.info Ear – Vestibular organ www.humanantomylibrary.com Nose/Sinus Anatomy Inferior Middle Turbinate Turbinate Septum Dorsum Sidewalls Ala Floor Tip www.ENT4Students.blogspot.com Columella Vestibule www.beautyepic.com Oral cavity and oropharynx (throat) www.apsubiology.org Neck www.rdhmag.com The Ear, Nose, and Throat exam Perform in a standardized systematic way that works for you Do it the same way every time, this mitigates risk of missing a portion of the exam Practice the exam to increase comfort with performance and familiarize self with variants of normal Describe what you are doing to the patient, describe what you see in your documentation Use your PPE as appropriate A question to keep in mind… ●T/F: The otoscope is the optimal tool for examining the tympanic membrane. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Silent Reflux (Also Called LPR Or EOR)

Silent reflux (also called LPR or EOR) This leaflet explains what your condition is, why it happens, what the symptoms are and how it can be managed. If there is anything you don’t understand or if you have any further questions please talk to your doctor or nurse. What is silent reflux? Everyone has juices in the stomach which are acidic and digest and break down food. At the top of the stomach there is a muscular valve which closes to prevent food and stomach juices escaping upwards into the gullet. If this muscular valve (oesophageal sphincter) does not work very well, the stomach juices can leak backwards into the gullet, causing reflux or symptoms of indigestion (heartburn). However, in some people, small amounts of stomach juice can spill even further back into the back of your throat, affecting the throat lining and your voice box (larynx) and causing irritation and hoarseness. This is known as laryngo pharyngeal reflux (LPR) or extra oesophageal reflux (EOR). Its common name is 'silent reflux' because many people do not experience any of the classic symptoms of heartburn or indigestion. Silent reflux can occur during the day or night, even if a person hasn't eaten anything. Usually, however, silent reflux occurs at night. What are the symptoms of silent reflux? The most common symptoms are: • A sensation of food sticking or a feeling of a lump in the throat. • A hoarse, tight or 'croaky' voice. • Frequent throat clearing. • Difficulty swallowing (especially tablets or solid foods). • A sore, dry and sensitive throat. • Occasional unpleasant "acid" or "bilious" taste at the back of the mouth. -

Larynx, Hypopharynx and Mandible Injury Due to External Penetrating Neck Injury

Turkish Journal of Trauma & Emergency Surgery Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2013;19 (3):271-273 Case Report Olgu Sunumu doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2013.58259 Larynx, hypopharynx and mandible injury due to external penetrating neck injury Eksternal penetran boyun yaralanmasına bağlı gelişen larinks, hipofarinks ve mandibula yaralanması Gül ÖZBİLEN ACAR, Muhammet TEKİN, Osman H. ÇAM, Emre KAYTANCI Esophageal and laryngeal injuries due to ballistic injuries are Blastik travmalara bağlı özöfageal ve laringeal yaralanma- seldom encountered. Ballistic external neck traumas gener- lar nadir görülürler. Blastik travmalara bağlı gelişen dış ally result in death. Incidence of external penetrant neck boyun travmaları genellikle ölümle sonuçlanır. Penetran injuries may vary between 1/5000-137000 patients among dış boyun travmalarının acil servise başvuran hastalar ara- emergency service referrals. Vascular injuries, esophagus- sındaki insidansı 1/5000-137000 arasında değişmektedir. hypopharynx perforations, laryngotracheal injuries, bony Dış boyun travmalarında vasküler yaralanmalar, özofa- fractures, and segmentations may be encountered in exter- gus-hipofarenks perforasyonları, laringotrakeal yaralan- nal neck traumas. Here we report a 27-year-old male pa- malar, kemik yapılarda kırık ve parçalanmalar görülebilir. tient who was referred to our emergency department and Bu yazıda, eksternal blastik boyun travmasına bağlı ola- presented with hyoid bone fracture, multiple mandibular rak acil servise başvuran hiyoid kırığı, multipl mandibula fractures, and hypopharynx -

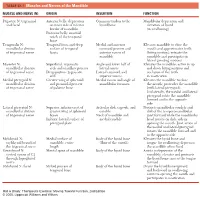

1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible

0350 ch 23-Tab 10/12/04 12:19 PM Page 1 Chapter 23: The Temporomandibular Joint 1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible MUSCLE AND NERVE (N) ORIGIN INSERTION FUNCTION Digastric N: trigeminal Anterior belly: depression Common tendon to the Mandibular depression and and facial on inner side of inferior hyoid bone elevation of hyoid border of mandible (in swallowing) Posterior belly: mastoid notch of the temporal bone Temporalis N: Temporal fossa and deep Medial and anterior Elevates mandible to close the mandibular division surface of temporal coronoid process and mouth and approximates teeth of trigeminal nerve fascia anterior ramus of (biting motion); retracts the mandible mandible and participates in lateral grinding motions Masseter N: Superficial: zygomatic Angle and lower half of Elevates the mandible; active in up mandibular division arch and maxillary process lateral ramus and down biting motions and of trigeminal nerve Deep portion: zygomatic Lateral coronoid and occlusion of the teeth arch superior ramus in mastication Medial pterygoid N: Greater wing of sphenoid Medial ramus and angle of Elevates the mandible to close mandibular division and pyramidal process mandibular foramen the mouth; protrudes the mandible of trigeminal nerve of palatine bone (with lateral pterygoid). Unilaterally, the medial and lateral pterygoid rotate the mandible forward and to the opposite side Lateral pterygoid N: Superior: inferior crest of Articular disk, capsule, and Protracts mandibular condyle and mandibular division greater wing of sphenoid condyle disk of the temporomandibular of trigeminal nerve bones Neck of mandible and joint forward while the mandibular Inferior: lateral surface of medial condyle head rotates on disk; aids in pterygoid plate opening the mouth. -

Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer and the Human Papillomavirus

MONOGRAPH HEAD AND NECK SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER AND THE HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS: SUMMARY OF A NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE STATE OF THE SCIENCE MEETING, NOVEMBER 9–10, 2008, WASHINGTON, D.C. David J. Adelstein, MD,1 John A. Ridge, MD, PhD,2 Maura L. Gillison, MD, PhD,3 Anil K. Chaturvedi, PhD,4 Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD,5 Patti E. Gravitt, PhD,5 William Westra, MD,6 Amanda Psyrri, MD, PhD,7 W. Martin Kast, PhD,8 Laura A. Koutsky, PhD,9 Anna Giuliano, PhD,10 Steven Krosnick, MD,4 Andy Trotti, MD,10 David E. Schuller, MD,3 Arlene Forastiere, MD,6 Claudio Dansky Ullmann, MD4 1 Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland, Ohio. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 3 Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, Ohio 4 National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland 5 Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 6 Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland 7 Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut 8 University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 9 University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 10 H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida Accepted 14 August 2009 Published online 29 September 2009 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hed.21269 VC 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Head Neck 31: 1393–1422, 2009* Keywords: human papillomavirus; head and neck squamous Correspondence to: D. J. Adelstein cell cancer; state of the science Contract grant sponsor: NIH. Gypsyamber D’Souza is an advisory board member and received For the purpose of clinical trials, head and neck research funding from Merck Co. -

Anatomy of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Anatomy of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Marlene M. Corton, MD KEYWORDS Pelvic floor Levator ani muscles Pelvic connective tissue Ureter Retropubic space Prevesical space NORMAL PELVIC ORGAN SUPPORT The main support of the uterus and vagina is provided by the interaction between the levator ani (LA) muscles (Fig. 1) and the connective tissue that attaches the cervix and vagina to the pelvic walls (Fig. 2).1 The relative contribution of the connective tissue and levator ani muscles to the normal support anatomy has been the subject of controversy for more than a century.2–5 Consequently, many inconsistencies in termi- nology are found in the literature describing pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue. The information presented in this article is based on a current review of the literature. LEVATOR ANI MUSCLE SUPPORT The LA muscles are the most important muscles in the pelvic floor and represent a crit- ical component of pelvic organ support (see Fig. 1). The normal levators maintain a constant state of contraction, thus providing an active floor that supports the weight of the abdominopelvic contents against the forces of intra-abdominal pressure.6 This action is thought to prevent constant or excessive strain on the pelvic ‘‘ligaments’’ and ‘‘fascia’’ (Fig. 3A). The normal resting contraction of the levators is maintained by the action of type I (slow twitch) fibers, which predominate in this muscle.7 This baseline activity of the levators keeps the urogenital hiatus (UGH) closed and draws the distal parts of the urethra, vagina, and rectum toward the pubic bones. Type II (fast twitch) muscle fibers allow for reflex muscle contraction elicited by sudden increases in abdominal pressure (Fig. -

Condylar Neck and Sub-Condylar Fractures: Surgical Consideration and Evolution of the Technique with Short Follow-Up on Five Cases

dentistry journal Article Condylar Neck and Sub-Condylar Fractures: Surgical Consideration and Evolution of the Technique with Short Follow-Up on Five Cases Antonio Cortese 1,* , Antonio Borri 1, Marco Bergaminelli 1, Fabrizio Bergaminelli 1 and Pier Paolo Claudio 2,3,4,* 1 Unit of Maxillofacial Surgery, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Salerno, 84084 Fisciano (Salerno), Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (F.B.) 2 Department of BioMolecular Sciences, National Center for Natural Product Research, University of Mississippi, University, MS 38677, USA 3 Department of Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA 4 Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS 39216, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (P.P.C.) Received: 2 September 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 3 November 2020 Abstract: Condylar neck and sub-condylar fractures of the mandible are a frequent occurrence in maxillofacial surgery. The indication for surgical treatment of these fractures has changed over time, and several techniques have been developed with different results in the attempt to avoid the most worrisome adverse event, i.e., facial nerve injury. In this study, we present a new technique that combines an intraoral and a cutaneous pre-auricular access, which allows for easy and safe access to the surgical site, preventing facial nerve injury and avoiding surgical scars in high-impact aesthetic areas of the neck. Five consecutive patients affected by condylar neck or sub-condylar fractures were treated at a single institution using a combined intraoral and pre-auricular access. -

Anatomical Terminology

Anatomical Terminology Because the unit we are currently studying involves the human body, it is necessary for you to familiarize yourself with some basic anatomical terminology as it relates to the human body. Directional Terms Directional terms describe the positions of structures relative to other structures or locations in the body. Superior or cranial - toward the head end of the body; upper (example, the hand is part of the superior extremity). Inferior or caudal - away from the head; lower (example, the foot is part of the inferior extremity). Anterior or ventral - front (example, the kneecap is located on the anterior side of the leg). Posterior or dorsal - back (example, the shoulder blades are located on the posterior side of the body). Medial - toward the midline of the body (example, the middle toe is located at the medial side of the foot). Lateral - away from the midline of the body (example, the little toe is located at the lateral side of the foot). Proximal - toward or nearest the trunk or the point of origin of a part (example, the proximal end of the femur joins with the pelvic bone). Distal - away from or farthest from the trunk or the point or origin of a part (example, the hand is located at the distal end of the forearm). Planes of the Body Coronal Plane (Frontal Plane) - A vertical plane running from side to side; divides the body or any of its parts into anterior and posterior portions. Sagittal Plane (Lateral Plane) - A vertical plane running from front to back; divides the body or any of its parts into right and left sides.