FEIS Appendix H, Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016

Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Revised February 24, 2017 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org C ur Alleghany rit Ashe Northampton Gates C uc Surry am k Stokes P d Rockingham Caswell Person Vance Warren a e P s n Hertford e qu Chowan r Granville q ot ui a Mountains Watauga Halifax m nk an Wilkes Yadkin s Mitchell Avery Forsyth Orange Guilford Franklin Bertie Alamance Durham Nash Yancey Alexander Madison Caldwell Davie Edgecombe Washington Tyrrell Iredell Martin Dare Burke Davidson Wake McDowell Randolph Chatham Wilson Buncombe Catawba Rowan Beaufort Haywood Pitt Swain Hyde Lee Lincoln Greene Rutherford Johnston Graham Henderson Jackson Cabarrus Montgomery Harnett Cleveland Wayne Polk Gaston Stanly Cherokee Macon Transylvania Lenoir Mecklenburg Moore Clay Pamlico Hoke Union d Cumberland Jones Anson on Sampson hm Duplin ic Craven Piedmont R nd tla Onslow Carteret co S Robeson Bladen Pender Sandhills Columbus New Hanover Tidewater Coastal Plain Brunswick THE COUNTIES AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC PROVINCES OF NORTH CAROLINA Natural Heritage Program List of Rare Plant Species of North Carolina 2016 Compiled by Laura Gadd Robinson, Botanist John T. Finnegan, Information Systems Manager North Carolina Natural Heritage Program N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Raleigh, NC 27699-1651 www.ncnhp.org This list is dynamic and is revised frequently as new data become available. New species are added to the list, and others are dropped from the list as appropriate. -

Status and Population Genetics of the Alabama Spike (Elliptio Arca) in the Mobile River Basin

STATUS AND POPULATION GENETICS OF THE ALABAMA SPIKE (ELLIPTIO ARCA) IN THE MOBILE RIVER BASIN A Thesis by DANIEL HUNT MASON Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August, 2017 Department of Biology STATUS AND POPULATION GENTICS OF THE ALABAMA SPIKE (ELLIPTIO ARCA) IN THE MOBILE RIVER BASIN A Thesis by DANIEL HUNT MASON August, 2017 APPROVED BY: Michael M. Gangloff, Ph.D. Chairperson, Thesis Committee Matthew C. Estep, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Lynn M. Siefermann, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Zack E. Murrell, Ph.D. Chairperson, Department of Biology Max C. Poole, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Daniel Hunt Mason 2017 All Rights Reserved Abstract STATUS AND POPULATION GENETICS OF THE ALABAMA SPIKE (ELLIPTIO ARCA) IN THE MOBILE RIVER BASIN Daniel H. Mason B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Dr. Michael M. Gangloff Declines in freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionioda) are widely reported but rarely rigorously tested. Additionally, the population genetics of most species are virtually unknown, despite the importance of these data when assessing the conservation status of and recovery strategies for imperiled mussels. Freshwater mussel endemism is high in the Mobile River Basin (MRB) and many range- restricted taxa have been heavily impacted by riverine alterations, and many species are suspected to be declining in abundance, including the Alabama Spike (Elliptio arca). I compiled historical and current distributional data from all major MRB drainages to quantify the extent of declines in E. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

An Analysis of Factors Potentially Affecting the Propagation And

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist Water Investigations Program Patrick E. O’Neil, Director FACTORS POTENTIALLY AFFECTING THE PROPAGATION AND REINTRODUCTION OF FRESHWATER MUSSELS (BIVALVIA: UNIONIDAE) INTO THE BUTTAHATCHEE RIVER SYSTEM, ALABAMA AND MISSISSIPPI Open File Report 0609 by Stuart W. McGregor, Marlon R. Cook, and Patrick E. O’Neil With field and laboratory assistance from Mirza A. Beg, Lifo Chen, Neil E. Moss, and Robert E. Meintzer Prepared in cooperation with the World Wildlife Fund Agreement Number LX 30 Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2006 CONTENTS Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ 2 Discussion........................................................................................................................ 2 Mussel fauna .............................................................................................................. 2 Sediment toxicity ....................................................................................................... 13 Sedimentation monitoring.......................................................................................... 21 Stream discharge.................................................................................................. 23 Sedimentation ..................................................................................................... -

OCCASIONAL PAPERS of the MUSEUM of ZOOLOGY UNIVERSITY of MICHIGAN Asx ARBOR,MICHIGAN

OCCASIONAL PAPERS OF THE MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Asx ARBOR,MICHIGAN ETHEOSTOAPA ACUTICEPS, .A NET41 DARTER FROM THE TENNESSEE RIVER SYSTEM, TWITH REMARKS ON THE SUBGENUS NOTHOATOTUS PRIOR10 the impoundment of the South Fork of thc I-Iolston River, Tennessee, a qualitative fish survey oT the area to be inundated was conducted by a party representing the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Tennessee Department of Conservation, and The University of Michigan. On the last day of field operations, September, 1947, two specimens of an undescribed darter were secured. In an attempt to obtain additional material the locality was revisited in June, 1949, by Gerald P. Cooper, John D. Kilby, and myself. Low water made success possible, because we found that the species was apparently confined to the deeper, faster riffles near the center of the stream. The darter was so rare that only four individuals were seined in three hours. The South Holston Reservoir is now full and the only known locality for Etheostomn acuticeps lies beneath 190 feet of water. Since it is unlikely that this swift-water species can tolerate quiet water, it is hoped that other stations of occurrence may be disco~.ered.To my companions in the field work, the late R. W. Eschmeyer, then with the Tennessee Valley Authority, Jack Chance, formerly with the Tennessee Department of Conservation, Gerald P. Cooper, Michigan Department of Conservation, and John D. Kilby, University of Flor- ida, I am sincerely grateful. For several years I have been assembling data leading toward a revision of the bluebreast darters (subgenus Nothonotus). -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

Proceedings of the United States National Museum SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION . WASHINGTON, D.C. Volume 119 1966 Number 3550 CATALOG OF TYPE SPECIMENS OF THE DARTERS (PISCES, PERCIDAE, ETHEOSTOMATINI) ^ By Bruce B. Collette and Leslie W. Knapp ^ Introduction The darters are a tribe of small freshwater fishes restricted to North America. Some 212 specific and subspecific names have been pro- posed for the approximately 100 vahd described species. About a dozen species await description. As part of a long-term study of these fishes, we have prepared this catalog of type specimens. We hope that our efforts will be of value in furthering systematic research and stabilizing the nomenclature of this most fascinating group of North American fishes. In preparing this catalog we have attempted to examine or at least to verify the location of the type specimens of all nominal forms of the three presently recognized genera of darters: Percina, Ammo- crypta, and Etheostoma. By type specimens we mean holotypes, lectotypes, syntypes, paralectotypes, and paratypes. Each form is ' Fifth paper in a series on the systematics of the Percidae by the senior author. 2 Collette: Assistant Laboratory Director, Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Ichthyological Laboratory, Division of Fishes, U.S. National Museum; Knapp: Supervisor in charge of vertebrates, Oceanographic Sorting Center, Smithsonian Institution. a 2 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. 119 listed in alphabetical order by the generic and specific name used in the original description. If subgeneric allocation was made in the original description, that name has been placed in parentheses between the genus and the species. Holotypes or lectotypes are listed before paratypes or paralectotypes. -

Impact of Introduced Red Shiners, Cyprinella Lutrensis, on Stream Fishes Near Atlanta, Georgia

IMPACT OF INTRODUCED RED SHINERS, CYPRINELLA LUTRENSIS, ON STREAM FISHES NEAR ATLANTA, GEORGIA Joseph C. DeVivo AUTHOR: Joseph C. DeVivo, M.S. student, Conservation Ecology and Sustainable Development, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602-2202. REFERENCE: Proceedings of the 1995 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held April 11 and April 12, 1995, at The University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, Editor, Carl Vinson Institute of Government, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Abstract. The red shiner, Cyprinella lutrensis, is native to of C. lutrensis within streams near Atlanta, Georgia; and 4) watersheds in the south- and central-plains states west of the management strategies for the control of C. lutrensis populations Mississippi River, but its use as a bait fish for sport fishing has within the ACF River basin resulted in its introduction in many watersheds across the country. Cyprinella lutrensis is a tolerant generalist that typically thrives in degraded waters. Historically, the introduction of C. lutrensis CYPRINELLA LUTRENSIS IN ITS NATIVE RANGE has resulted in significant shifts in fish assemblages, either as a result of displacement of native fishes, or by hybridization with Cyprinella lutrensis is a cyprinid native to watersheds of the congeneric fishes. Cyprinella lutrensis has been introduced into south- and central-plains states west of the Mississippi River the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River basin and (Page and Burr, 1991). Although its morphology is thrives particularly in the impacted streams near Atlanta, Georgia. geographically variable, it can be easily identified by its deep- Fish samples collected near Atlanta by the National Water Quality body and bright red fins on breeding males (Matthews, 1987). -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 1 8(2): 143—1 86

2009. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 1 1 8(2): 143—1 86 THE "LOST" JORDAN AND HAY FISH COLLECTION AT BUTLER UNIVERSITY Carter R. Gilbert: Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611 USA ABSTRACT. A large fish collection, preserved in ethanol and assembled by Drs. David S. Jordan and Oliver P. Hay between 1875 and 1892, had been stored for over a century in the biology building at Butler University. The collection was of historical importance since it contained some of the earliest fish material ever recorded from the states of South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi and Kansas, and also included types of many new species collected during the course of this work. In addition to material collected by Jordan and Hay, the collection also included specimens received by Butler University during the early 1880s from the Smithsonian Institution, in exchange for material (including many types) sent to that institution. Many ichthyologists had assumed that Jordan, upon his departure from Butler in 1879. had taken the collection. essentially intact, to Indiana University, where soon thereafter (in July 1883) it was destroyed by fire. The present study confirms that most of the collection was probably transferred to Indiana, but that significant parts of it remained at Butler. The most important results of this study are: a) analysis of the size and content of the existing Butler fish collection; b) discovery of four specimens of Micropterus coosae in the Saluda River collection, since the species had long been thought to have been introduced into that river; and c) the conclusion that none of Jordan's 1878 southeastern collections apparently remain and were probably taken intact to Indiana University, where they were lost in the 1883 fire. -

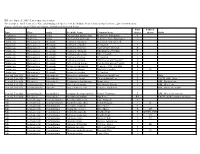

Threatened and Endangered Species List

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

BRM SOP Part V 20110408

Part V: Scoring Criteria for the Index of Biotic Integrity and the Index of Well-Being to Monitor Fish Communities in Wadeable Streams in the Coosa and Tennessee River Basins of the Blue Ridge Ecoregion of Georgia Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Fisheries Management Section Stream Survey Team May 23, 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………….…...3 Figure 1: Map of Blue Ridge Ecoregion………………………….………..…6 Table 1: Listed Fish in the Blue Ridge Ecoregion………………………..…..7 Table 2: Metrics and Scoring Criteria………………………………..….…....8 Table 3: Iwb Metric and Scoring Criteria………………………….…….…..10 Figure 2: Multidimensional scaling ordination plot……………………….....11 Table 4: High Elevation criteria……………………………………….….....12 References………………………………………………………...………….13 Appendix A……………………………………………………………..……A1 Appendix B……………………………………………………….………….B1 2 Introduction The Blue Ridge ecoregion (BRM), one of Georgia’s six Level III ecoregions (Griffith et al. 2001), forms the boundary for the development of this fish index of biotic integrity (IBI). Encompassing approximately 2,639 mi2 in northeast Georgia, the BRM includes portions of four major river basins — the Chattahoochee (CHT, 142.2 mi2), Coosa (COO, 1257.5 mi2), Savannah (SAV, 345.3 mi2), and Tennessee (TEN, 894.2 mi2) — and all or part of 16 counties (Figure 1). Due to the relatively small watershed areas and physical and biological parameters of the CHT and SAV basins within the BRM, and the resulting low number of sampled sites, IBI scoring criteria have not been developed for these basins. Therefore, only sites in the COO and TEN basins, meeting the criteria set forth in this document, should be scored with the following metrics. The metrics and scoring criteria adopted for the BRM IBI were developed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division (GAWRD), Stream Survey Team using data collected from 154 streams by GAWRD within the COO (89 sites) and TEN (65 sites) basins. -

The Tombigbee River Basin

Contents Water—Our Precious Natural Resource. 3 Mississippi’s Water Resources . 4 Welcome to the Tombigbee and Tennessee River Basins . 6 Special Plants and Animals of the Tombigbee and Tennessee . 10 Land Use and Its Effects on Water Quality . 13 Water Quality in the Tombigbee and Tennessee River Basins . 17 Mississippi’s Basin Management Approach . 21 Priority Watersheds . 22 Agencies and Organizations Cooperating for Improved Water Quality . 30 Sustaining Our Environmental Resources and Economic Development . 31 About this Guide Acknowledgments Mississippi’s Citizen’s Guides to Water Quality This guide is a product of the Basin Team for the are intended to inform you about: Tombigbee and Tennessee River Basins, consisting of representatives from 28 state Mississippi’s abundant water resources and federal agencies and stakeholder Natural features, human activities, and organizations (see page 30 of this document for water quality in a particular river basin a complete listing). The lead agency for developing, distributing, and funding this guide The importance of a healthy environment is the Mississippi Department of Environmental to a strong economy Quality (MDEQ). This effort was completed in 2008 under a Clean Water Act Section 319 Watersheds targeted for water quality restoration and protection activities Nonpoint Source grant, and includes publication services from Tetra Tech, Inc. How to participate in protecting or Copies of this guide may be obtained by restoring water quality contacting: Mississippi Department of Whom to contact for more information Environmental Quality Office of Pollution Control We hope these guides will enhance the 515 East Amite Street dialogue between citizens and key decision Jackson, MS 39201 makers to help improve our management of 601-961-5171 Mississippi’s precious water resources.