Acceptability, Conflict, and Supporter Coastal Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 Projects

Annual Infrastructure Program Revisions Flag: (D)elisted; (M)odified; (R)ealigned; (T)erminated Operating Unit/ Revisions UACS PAP Project Component Decsription Project Component ID Type of Work Target Unit Target Allocation Implementing Office Flag Region VII 16,336,491,000 936 projects GAA 2016 MFO-1 7,959,170,000 202 projects Bohol 1st District Engineering Office 1,498,045,000 69 projects BOHOL (FIRST DISTRICT) Network Development - Off-Carriageway Improvement including drainage 165003015600115 Tagbilaran East Rd (Tagbilaran-Jagna) - K0248+000 - K0248+412, P00003472VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,609 62,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0248+950 - K0249+696, K0253+000 - K0253+215, K0253+880 - Improvement: Shoulder K0254+701 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Paving / Construction Construction 165003015600117 Tagbilaran North Rd (Tagbilaran-Jetafe Sect) - K0026+000 - K0027+ P00003476VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 6,828 49,500,000 Bohol 1st District 540, K0027+850 - K0028+560 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office 165003015600225 Jct (TNR) Cortes-Balilihan-Catigbian-Macaas Rd - K0009+-130 - P00003653VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 9,777 91,000,000 Region VII / Region VII K0010+382, K0020+000 - K0021+745 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Construction Paving / Construction 165003015600226 Jct. (TNR) Maribojoc-Antequera-Catagbacan (Loon) - K0017+445 - P00015037VS-CW1 Off-Carriageway Square meters 3,141 32,000,000 Bohol 1st District K0018+495 - Off-Carriageway Improvement: Shoulder Paving / Improvement: Shoulder Engineering Office / Bohol Construction Paving / Construction 1st District Engineering Office Construction and Maintenance of Bridges along National Roads - Retrofitting/ Strengthening of Permanent Bridges 165003016100100 Camayaan Br. -

Coastal Law Enforcement

8 Coastal law enforcement units must be formed and functional in all coastal LGUs to promote voluntary compliance with and to apprehend violators of national and local laws and regulations. This guidebook was produced by: Department of Department of the Department of Environment and Interior and Local Agriculture - Bureau of Natural Resources Government Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Local Government Units, Nongovernment Organizations, and other Assisting Organizations through the Coastal Resource Management Project, a technical assistance project supported by the United States Agency for International Development. Technical support and management is provided by: The Coastal Resource Management Project, 5/F Cebu International Finance Corporation Towers J. Luna Ave. cor. J.L. Briones St., North Reclamation Area 6000 Cebu City, Philippines Tels.: (63-32) 232-1821 to 22, 412-0487 to 89 Fax: (63-32) 232-1825 Hotline: 1-800-1888-1823 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.oneocean.org PHILIPPINE COASTAL MANAGEMENT GUIDEBOOK SERIES NO. 8: COASTAL LAW ENFORCEMENT By: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture Department of the Interior and Local Government and Coastal Resource Management Project of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources supported by the United States Agency for International Development Philippines PHILIPPINE COASTAL MANAGEMENT GUIDEBOOK SERIES NO. 8 Coastal Law Enforcement by Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture (DA-BFAR) Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) and Coastal Resource Management Project (CRMP) 2001 Printed in Cebu City, Philippines Citation: Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture, and Department of the Interior and Local Government. -

Icc-Wcf-Competition-Negros-Oriental-Cci-Philippines.Pdf

World Chambers Competition Best job creation and business development project Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry The Philippines FINALIST I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Negros Oriental Chamber of Commerce and Industry Inc. (NOCCI), being the only recognized voice of business in the Province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, developed the TIP PROJECT or the TRADE TOURISM and INVESTMENT PROMOTION ("TIP" for short) PROJECT to support its mission in conducting trade, tourism and investment promotion, business development activities and enhancement of the business environment of the Province of Negros Oriental. The TIP Project was conceptualized during the last quarter of 2013 and was launched in January, 2014 as the banner project of the Chamber to support its new advocacy for inclusive growth and local economic development through job creation and investment promotion. The banner project was coined from the word “tip” - which means giving sound business advice or sharing relevant information and expertise to all investors, businessmen, local government officials and development partners. The TIP Project was also conceptualized to highlight the significant role and contribution of NOCCI as a champion for local economic development and as a banner project of the Chamber to celebrate its Silver 25th Anniversary by December, 2016. For two years, from January, 2015 to December, 2016, NOCCI worked closely with its various partners in local economic development like the Provincial Government, Local Government Units (LGUs), National Government Agencies (NGAs), Non- Government Organizations (NGOs), Industry Associations and international funding agencies in implementing its various job creation programs and investment promotion activities to market Negros Oriental as an ideal investment/business destination for tourism, retirement, retail, business process outsourcing, power/energy and agro-industrial projects. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

SOIL Ph MAP N N a H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA a ( Key Rice Areas ) IL

Sheet 1 of 2 124°0' 124°30' 124°0' R E P U B L I C O F T H E P H I L I P P I N E S Car ig ar a Bay D E PA R T M E N T O F A G R IIC U L T U R E Madridejos BURE AU OF SOILS AND Daanbantayan WAT ER MANAGEMENT Elliptical Roa d Cor. Visa yas Ave., Diliman, Quezon City Bantayan Province of Santa Fe V IS A Y A N S E A Leyte Hagnaya Bay Medellin E L San Remigio SOIL pH MAP N N A H C Bogo City N O CAMOT ES SEA CA A ( Key Rice Areas ) IL 11°0' 11°0' A S Port Bello PROVINCE OF CEBU U N C Orm oc Bay IO N P Tabogon A S S Tabogon Bay SCALE 1:300,000 2 0 2 4 6 8 Borbon Tabuelan Kilom eter s Pilar Projection : Transverse Mercator Datum : PRS 1992 Sogod DISCLAIMER : All political boundaries are not authoritative Tuburan Catmon Province of Negros Occidental San Francisco LOCATION MA P Poro Tudela T I A R T S Agusan Del S ur N Carmen O Dawis Norte Ñ A Asturias T CAMOT ES SEA Leyte Danao City Balamban 11° LU Z O N 15° Negros Compostela Occi denta l U B E Sheet1 C F O Liloan E Toledo City C Consolacion N I V 10° Mandaue City O R 10° P Magellan Bay VIS AYAS CEBU CITY Bohol Lapu-Lapu City Pinamungajan Minglanilla Dumlog Cordova M IN DA NA O 11°30' 11°30' 5° Aloguinsan Talisay 124° 120° 125° ColonNaga T San Isidro I San Fernando A R T S T I L A O R H T O S Barili B N Carcar O Ñ A T Dumanjug Sibonga Ronda 10°0' 10°0' Alcantara Moalboal Cabulao Bay Badian Bay Argao Badian Province of Bohol Cogton Bay T Dalaguete I A R T S Alegria L O H O Alcoy B Legaspi ( ilamlang) Maribojoc Bay Guin dulm an Bay Malabuyoc Boljoon Madridejos Ginatilan Samboan Oslob B O H O L S E A PROVINCE OF CEBU SCALE 1:1,000,000 T 0 2 4 8 12 16 A Ñ T O Kilo m e te r s A N Ñ S O T N Daanbantayan R Santander S A T I Prov. -

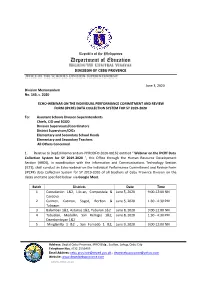

Memo No. 163 S. 2020

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education DIVISION OF CEBU PROVINCE June 3, 2020 Division Memorandum No. 163, s. 2020 ECHO-WEBINAR ON THE INDIVIDUAL PERFORMANCE COMMITMENT AND REVIEW FORM (IPCRF) DATA COLLECTION SYSTEM FOR SY 2019-2020 To: Assistant Schools Division Superintendents Chiefs, CID and SGOD Division Supervisors/Coordinators District Supervisors/OICs Elementary and Secondary School Heads Elementary and Secondary Teachers All Others Concerned 1. Relative to DepEd Memorandum-PHRODFO-2020-00162 entitled “ Webinar on the IPCRF Data Collection System for SY 2019-2020 “, this Office through the Human Resource Development Section (HRDS), in coordination with the Information and Communications Technology Section (ICTS), shall conduct an Echo-webinar on the Individual Performance Commitment and Review Form (IPCRF) data Collection System for SY 2019-2020 of all teachers of Cebu Province Division on the dates and time specified below via Google Meet. Batch Districts Date Time 1 Consolacion 1&2, Lilo-an, Compostela & June 5, 2020 9:00-12:00 NN Cordova 2 Carmen, Catmon, Sogod, Borbon & June 5, 2020 1:30 - 4:30 PM Tabogon 3 Balamban 1&2, Asturias 1&2, Tuburan 1&2 June 8, 2020 9:00-12:00 NN 4 Tabuelan, Medellin, San Remigio 1&2, June 8, 2020 1:30 - 4:30 PM Daanbantayan 1&2 5 Minglanilla 1 &2 , San Fernado 1 &2, June 9, 2020 9:00-12:00 NN Address: DepEd Cebu Province, IPHO Bldg., Sudlon, Lahug, Cebu City Telephone Nos.: 032-2556405 Email Address: [email protected] ; [email protected] Website: www.depedcebuprovince.com SEPS-HRD 2020 Sibonga 6 Argao 1 & 2, Dalaguete 1&2, Boljoon & June 9, 2020 1:30 - 4:30 PM Alcoy 7 Samboan, Ginatilan, Malabuyoc, Alegria, June 10, 2020 9:00-12:00 NN Badian & Moalboal 8 Alcantara, Ronda, Dumanjug 1 & 2 , Barili 1 June 10, 2020 1:30 - 4:30 PM & 2, Aloguinsan 9 San Francisco, Pilar, Poro , Tudela, Oslob & June 11, 2020 9:00-12:00 NN Santander 10 Santa Fe, Madridejos, Bantayan 1 & 2, June 11, 2020 1:30 - 4:30 PM Pinamungajan 1&2 2. -

Tuna Fishing and a Review of Payaos in the Philippines

Session 1 - Regional syntheses Tuna fishing and a review of payaos in the Philippines Jonathan O. Dickson*1', Augusto C. Nativiclacl(2) (1) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, 860 Arcadia Bldg., Quezon Avenue, Quezon City 3008, Philippines - [email protected] (2) Frabelle Fishing Company, 1051 North Bay Blvd., Navotas, Metro Manila, Philippines Abstract Payao is a traditional concept, which has been successfully commercialized to increase the landings of several species valuable to the country's export and local industries. It has become one of the most important developments in pelagic fishing that significantly contributed to increased tuna production and expansion of purse seine and other fishing gears. The introduction of the payao in tuna fishing in 1975 triggered the rapid development of the tuna and small pelagic fishery. With limited management schemes and strategies, however, unstable tuna and tuna-like species production was experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. In this paper, the evolution and development of the payao with emphasis on the technological aspect are reviewed. The present practices and techniques of payao in various parts of the country, including its structure, ownership, distribution, and fishing operations are discussed. Monitoring results of purse seine/ringnet operations including handline using payao in Celebes Sea and Western Luzon are presented to compare fishing styles and techniques, payao designs and species caught. The fishing gears in various regions of the country for harvesting payao are enumerated and discussed. The inshore and offshore payaos in terms of sea depth, location, designs, fishing methods and catch composi- tion are also compared. Fishing companies and fisherfolk associations involved in payao operation are presented to determine extent of uti- lization and involvement in the municipal and commercial sectors of the fishing industry. -

Ecology and Behaviour of Tarsius Syrichta in the Wild

O',F Tarsius syrichta ECOLOGY AND BEHAVIOUR - IN BOHOL, PHILIPPINES: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONSERVATION By Irene Neri-Arboleda D.V.M. A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Applied Science Department of Applied and Molecular Ecology University of Adelaide, South Australia 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS DAge Title Page I Table of Contents............ 2 List of Tables..... 6 List of Figures.... 8 Acknowledgements... 10 Dedication 11 I)eclaration............ t2 Abstract.. 13 Chapter I GENERAL INTRODUCTION... l5 1.1 Philippine Biodiversity ........... t6 1.2 Thesis Format.... l9 1.3 Project Aims....... 20 Chapter 2 REVIEIV OF TARSIER BIOLOGY...... 2t 2.1 History and Distribution..... 22 2.t.1 History of Discovery... .. 22 2.1.2 Distribution...... 24 2.1.3 Subspecies of T. syrichta...... 24 2.2 Behaviour and Ecology.......... 27 2.2.1 Home Ranges. 27 2.2.2 Social Structure... 30 2.2.3 Reproductive Behaviour... 3l 2.2.4 Diet and Feeding Behaviour 32 2.2.5 Locomotion and Activity Patterns. 34 2.2.6 Population Density. 36 2.2.7 Habitat Preferences... ... 37 2.3 Summary of Review. 40 Chapter 3 FßLD SITE AI\D GEIYERAL METHODS.-..-....... 42 3.1 Field Site........ 43 3. 1.1 Geological History of the Philippines 43 3.1.2 Research Area: Corella, Bohol. 44 3.1.3 Physical Setting. 47 3.t.4 Climate. 47 3.1.5 Flora.. 50 3.1.6 Fauna. 53 3.1.7 Human Population 54 t page 3.1.8 Tourism 55 3.2 Methods.. 55 3.2.1 Mapping. -

Or Negros Oriental

CITY CANLAON CITY LAKE BALINSASAYAO KANLAON VOLCANO VALLEHERMOSO Sibulan - The two inland bodies of Canlaon City - is the most imposing water amid lush tropical forests, with landmark in Negros Island and one of dense canopies, cool and refreshing the most active volcanoes in the air, crystal clear mineral waters with Philippines. At 2,435 meters above sea brushes and grasses in all hues of level, Mt. Kanlaon has the highest peak in Central Philippines. green. Balinsasayaw and Danao are GUIHULNGAN CITY 1,000 meters above sea level and are located 20 kilometers west of the LA LIBERTAD municipality of Sibulan. JIMALALUD TAYASAN AYUNGON MABINAY BINDOY MANJUYOD BAIS CITY TANJAY OLDEST TREE BAYAWAN CITY AMLAN Canlaon City - reportedly the oldest BASAY tree in the Philipines, this huge PAMPLONA SAN JOSE balete tree is estimated to be more NILUDHAN FALLS than a thousand years old. SIBULAN Sitio Niludhan, Barangay Dawis, STA. CATALINA DUMAGUETE Bayawan City - this towering cascade is CITY located near a main road. TAÑON STRAIT BACONG ZAMBOANGUITA Bais City - Bais is popular for its - dolphin and whale-watching activities. The months of May and September are ideal months SIATON for this activity where one can get a one-of-a kind experience PANDALIHAN CAVE with the sea’s very friendly and intelligent creatures. Mabinay - One of the hundred listed caves in Mabinay, it has huge caverns, where stalactites and stalagmites APO ISLAND abound. The cave is accessible by foot and has Dauin - An internationally- an open ceiling at the opposite acclaimed dive site with end. spectacular coral gardens and a cornucopia of marine life; accessible by pumpboat from Zamboanguita. -

PESO-Region 7

REGION VII – PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT SERVICE OFFICES PROVINCE PESO Office Classification Address Contact number Fax number E-mail address PESO Manager Local Chief Executive Provincial Capitol , (032)2535710/2556 [email protected]/mathe Cebu Province Provincial Cebu 235 2548842 [email protected] Mathea M. Baguia Hon. Gwendolyn Garcia Municipal Hall, Alcantara, (032)4735587/4735 Alcantara Municipality Cebu 664 (032)4739199 Teresita Dinolan Hon. Prudencio Barino, Jr. Municipal Hall, (032)4839183/4839 Ferdinand Edward Alcoy Municipality Alcoy, Cebu 184 4839183 [email protected] Mercado Hon. Nicomedes A. de los Santos Municipal Alegria Municipality Hall, Alegria, Cebu (032)4768125 Rey E. Peque Hon. Emelita Guisadio Municipal Hall, Aloquinsan, (032)4699034 Aloquinsan Municipality Cebu loc.18 (032)4699034 loc.18 Nacianzino A.Manigos Hon. Augustus CeasarMoreno Municipal (032)3677111/3677 (032)3677430 / Argao Municipality Hall, Argao, Cebu 430 4858011 [email protected] Geymar N. Pamat Hon. Edsel L. Galeos Municipal Hall, (032)4649042/4649 Asturias Municipality Asturias, Cebu 172 loc 104 [email protected] Mustiola B. Aventuna Hon. Allan L. Adlawan Municipal (032)4759118/4755 [email protected] Badian Municipality Hall, Badian, Cebu 533 4759118 m Anecita A. Bruce Hon. Robburt Librando Municipal Hall, Balamban, (032)4650315/9278 Balamban Municipality Cebu 127782 (032)3332190 / Merlita P. Milan Hon. Ace Stefan V.Binghay Municipal Hall, Bantayan, melitanegapatan@yahoo. Bantayan Municipality Cebu (032)3525247 3525190 / 4609028 com Melita Negapatan Hon. Ian Escario Municipal (032)4709007/ Barili Municipality Hall, Barili, Cebu 4709008 loc. 130 4709006 [email protected] Wilijado Carreon Hon. Teresito P. Mariñas (032)2512016/2512 City Hall, Bogo, 001/ Bogo City City Cebu 906464033 [email protected] Elvira Cueva Hon. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

Philippines Country Report (Global Fisheries MCS Report 2020)

GLOBAL EVALUATION OF FISHERIES MONITORING CONTROL AND SURVEILLANCE IN 84 COUNTRIES PHILIPPINES – COUNTRY REPORT GANAPATHIRAJU PRAMOD IUU RISK INTELLIGENCE Policy Report - Volume 1 Number 1 © Pramod Ganapathiraju JANUARY 2020 SUMMARY This evaluation of Fisheries Monitoring Control and Surveillance report for Philippines is one of 84 such country evaluations that covers nations landing 92% of world’s fish catch. Using a wide range of interviews and in-country consultations with both military and civilian agencies, the report exemplifies the best attempt by the author(s) at evaluation of MCS compliance using 12 questions derived from international fisheries laws. The twelve questions are divided into two evaluation fields, (MCS Infrastructure and Inspections). Complete details of the methods and results of this global evaluation would be published shortly through IUU Risk Intelligence website. Over a five-year period, this global assessment has been subjected to several cross-checks from both regional and global MCS experts familiar with compliance aspects in the country concerned. Uncertainty in assigning each score is depicted explicitly through score range. However, the author(s) are aware that gaps may remain for some aspects. The lead author remains open to comments, and revisions will be made upon submission of documentary evidence where necessary. Throughout the report, extreme precaution has been taken to maintain confidentiality of individuals who were willing to share information but expressed an inclination to remain anonymous out of concern for their job security, and information from such sources was cited as ‘anonymous’ throughout the report. Suggested citation: Pramod, G. (2020) Philippines – Country Report, 11 pages, In: Policing the Open Seas: Global Assessment of Fisheries Monitoring Control and Surveillance in 84 countries, IUU Risk Intelligence - Policy Report No.