Management of Wildlife, Tourism and Local Communities in Zimbabwe Discussion Paper No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

Proquest Dissertations

ARE PEACE PARKS EFFECTIVE PEACEBUILDING TOOLS? EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF GREAT LIMPOPO TRANSFRONTIER PARK AS A REGIONAL STABILIZING AGENT By Julie E. Darnell Submitted to the Faculty of the School oflntemational Service of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts m Ethics, Peace, and Global Affuirs Chair: ~~~Christos K yrou 1 lw') w Louis Goodman, Dean I tacfi~ \ Date 2008 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UMI Number: 1458244 Copyright 2008 by Darnell, Julie E. All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UM I M icroform 1458244 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by Julie E. Darnell 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ARE PEACE PARKS EFFECTIVE PEACEBUILDING TOOLS? EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF THE GREAT LIMPOPO TRANSFRONTIER PARK AS A REGIONAL STABILIZING AGENT BY Julie E. Darnell ABSTRACT In recent decades peace parks and transboundary parks in historically unstable regions have become popular solutions to addressing development, conservation and security goals. -

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority Commercial Revenue Model Assessment June 2014

Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority Commercial Revenue Model Assessment June 2014 Prepared by Conservation Capital with and on behalf of the African Wildlife Foundation 1 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. RLA-A- 00-07-00043-00. The contents are the responsibility of the Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group (ABCG). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. This publication was produced by African Wildlife Foundation on behalf of ABCG. CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction 2 2: Current Context 3 3: Optimising Revenue: Key Principles 3 4: The Current and Proposed ZPWMA Approach 9 6: Suggested Way Forward 11 7: Conclusions 15 Annexes 1. INTRODUCTION The African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) was invited by the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZPWMA) to conduct an assessment of its present commercial revenue model, with the aim of optimising revenue generation in support of Zimbabwe’s conservation estate and to enable ZPWMA to be financially sustainable. AWF has worked with protected area authorities across Africa to help plan, develop, expand and enhance protected areas, improve management of protected areas and to create new protected areas. AWF was requested to help ZPWMA to review their structure; assess operational needs and costs; evaluate revenue; and determine how the authority can revise its structure and/or strategy to maximize revenue to support protected area operations. -

Tourism, Biodiversity Conservation and Rural Communities in Zimbabwe

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.8, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania TOURISM, BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND RURAL COMMUNITIES IN ZIMBABWE: Shepherd Nyaruwata Leisure and Hospitality Management Department, Faculty of Commerce, University of Zimbabwe ABSTRACT The need to conserve Zimbabwe’s natural resources as a base for its tourism industry has encountered innumerable problems since independence. The majority of the resources are located in rural areas and directly impact rural livelihoods. An evaluation of the programmes implemented by the government on tourism development, biodiversity conservation and rural communities was undertaken. This entailed carrying out desk research on the topic covering developments in Zimbabwe, Southern Africa and selected parts of the world. Field research was undertaken on the following community based tourism enterprises (CBTEs): Gaerezi in Nyanga, Cholo/Mahenye in Chipinge and Ngomakurira in Goromonzi. The paper highlights the challenges that CBTEs face with regard to long term sustainability. Research findings include the need to improve national policies affecting CBTEs, lack of management capacity within the communities and inability to market the products offered. Recommendations aimed at improving the sustainability of CBTEs are provided. Keywords: Tourism; Biodiversity Conservation, Communities, Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources (CAMPFIRE) INTRODUCTION Zimbabwe’s tourism is mainly based on its varied natural resources ranging from wildlife, flora, water and outstanding physical features. The sustainability of the country’s biodiversity and hence the long-term sustainability of the tourism industry is dependent on the attitude of rural communities towards these resources. This is mainly due to the fact that most of the resources are located in areas that are adjacent to rural communities or within the rural communities. -

Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise 11-Day Zimbabwe Tour with 5-Day Lake Kariba Cruise

Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise 11-Day Zimbabwe Tour with 5-Day Lake Kariba Cruise Zambezi River Safari and Houseboat Cruise Discover one of Africa’s hidden treasures on an unforgettable journey amid Zimbabwe’s natural beauty. Explore magnificent waterfalls, pristine national parks, and enjoy thrilling wildlife safaris. Discover one of Africa’s hidden treasures on an unforgettable journey amid Zimbabwe’s natural beauty. Explore magnificent waterfalls, pristine national parks, and enjoy thrilling wildlife safaris. The Victoria Falls are one of the world’s most stunning natural wonders. Lake Kariba is the largest human-made lake in the world by volume. These are just two of the highlights of your exclusive houseboat adventure in Zimbabwe! What Makes Your Journey Unique • Experience the mighty Zambezi River • Enjoy a unique and exclusive cruise on Lake Kariba • Discover Zimbabwe on a houseboat featuring nine cabins, all with panoramic views • Visit the immense Victoria Falls, also known as the Smoke that Thunders • Explore the Mana Pools National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site • Go on a safari in the Matusadona National Park, home to all big five game animals Dates Info and Booking Susanne Willeke E-Mail: [email protected] Itinerary Day 1., Zimbabwe Welcomes You Your first day in Zimbabwe immediately gets off to the right start—with a smile from your driver. Once you arrive at your lodge, you begin to explore its amenities and surrounding areas. After lunch, you take advantage of your private balcony and gaze at the unfettered panorama of the gorgeous Zambezi National Park. A nearby watering hole attracts local wildlife, making for some beautiful and spontaneous photography sessions. -

African Pentecostalism, the Bible, and Cultural Resilience. the Case Of

24 BiAS - Bible in Africa Studies Exploring Religion in Africa 3 Kudzai Biri AFRICAN PENTECOSTALISM, THE BIBLE, AND CULTURAL RESILIENCE The Case of the Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa 24 Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien Exploring Religion in Africa 3 Bible in Africa Studies Études sur la Bible en Afrique Bibel-in-Afrika-Studien Volume 24 edited by Joachim Kügler, Lovemore Togarasei, Masiiwa R. Gunda In cooperation with Ezra Chitando and Nisbert Taringa (†) Exploring Religion in Africa 3 2020 African Pentecostalism, the Bible, and Cultural Resilience The Case of the Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa Kudzai Biri 2020 Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Informationen sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de/ abrufbar. Under the title African Pentecostalism and Cultural Resilience: The Case of ZAOGA submitted in 2013 to the Department of Religious Studies, Classics and Philosophy of the University of Zimbabwe, Harare, as a thesis for the degree Philosophiae Doctor (PhD). Defended with success in 2013. Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ezra Chitando Dieses Werk ist als freie Onlineversion über das Forschungsinformationssystem (FIS; https://fis.uni-bamberg.de) der Universität Bamberg erreichbar. Das Werk – ausgenommen Cover und Zitate – steht unter der CC-Lizenz CCBY. Lizenzvertrag: Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 -

THE IMPACT of ZIMBABWE TOURISM AUTHORITY INITIATIVES on TOURIST ARRIVALS in ZIMBAWE (2008 – 2009) Roseline T. Karambakuwa

Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Volume 13, No.6, 2011) ISSN: 1520-5509 Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania THE IMPACT OF ZIMBABWE TOURISM AUTHORITY INITIATIVES ON TOURIST ARRIVALS IN ZIMBAWE (2008 – 2009) Roseline T. Karambakuwa, Tonald Shonhiwa, Lydia Murombo, Fungai N Mauchi, Norah R.Gopo, Webster Denhere, Felex Tafirei, Anna Chingarande and Victoria Mudavanhu Bindura University of Science Education ABSTRACT Zimbabwe faced a decline in tourist arrivals in 2008 due to political instability, economic recession and negative media publicity. In 2009, a Government of National Unity (GNU) was formed and a multi currency system was introduced. This study analyses the impact of Zimbabwe Tourism Authority initiatives on tourist arrivals for the period 2008 to 2009. Fifty questionnaires were distributed to a sample of six stratified tourism stakeholders, including the Zimbabwe Tourism Authority. Secondary data analysis complimented the questionnaires. The study found out that tourist arrivals declined in Zimbabwe during the period 2008 and ZTA initiatives did not have much impact on tourist arrivals during that period. Initiatives by ZTA had a positive impact on arrival of tourists in Zimbabwe in 2009 after the formation of the Government of National Unity (GNU) and introduction of a multi currency system. Keywords: Tourism, Zimbabwe Tourism Authority, Economy INTRODUCTION Tourism in Zimbabwe Tourism was amongst the fastest growing sectors of the economy in Zimbabwe contributing significantly to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during the period 1980 to 2000. The highest growth rate was in 1995 when Zimbabwe hosted the All Africa Games which saw a 35% increase in tourist arrivals. However, the years 2002 to 2008 saw tourist arrivals dwindling in Zimbabwe (Machipisa, 2001). -

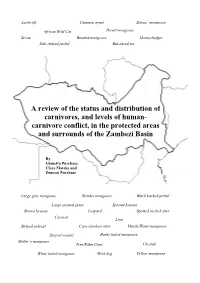

A Review of the Status and Distribution of Carnivores, and Levels of Human- Carnivore Conflict, in the Protected Areas and Surrounds of the Zambezi Basin

Aardwolf Common genet Selous’ mongoose African Wild Cat Dwarf mongoose Serval Banded mongoose Honey badger Side striped jackal Bat-eared fox A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human- carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin By Gianetta Purchase, Clare Mateke and Duncan Purchase Large grey mongoose Slender mongoose Black backed jackal Large spotted genet Spotted hyaena Brown hyaena Leopard Spotted necked otter Caracal Lion Striped polecat Cape clawless otter Marsh/Water mongoose Striped weasel Bushy tailed mongoose Meller’s mongoose Tree/Palm Civet Cheetah White tailed mongoose Wild dog Yellow mongoose A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human- carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin By Gianetta Purchase, Clare Mateke and Duncan Purchase © The Zambezi Society 2007 Suggested citation Purchase, G.K., Mateke, C. & Purchase, D. 2007. A review of the status and distribution of carnivores, and levels of human carnivore conflict, in the protected areas and surrounds of the Zambezi Basin. Unpublished report. The Zambezi Society, Bulawayo. 79pp Mission Statement To promote the conservation and environmentally sound management of the Zambezi Basin for the benefit of its biological and human communities THE ZAMBEZI SOCIETY was established in 1982. Its goals include the conservation of biological diversity and wilderness in the Zambezi Basin through the application of sustainable, scientifically sound natural resource management strategies. Through its skills and experience in advocacy and information dissemination, it interprets biodiversity information collected by specialists, and uses it to implement technically sound conservation projects within the Zambezi Basin. -

Zimbabwe Deluxe

Zimbabwe Deluxe Your professional partner for perfectly organised travel arrangements to Southern and Eastern Africa since more than 15 years Zimbabwe Deluxe Selected properties Combination of privately guided tour and Fly-in safari with guide from the respective camps Victoria Falls - Hwange National Park – Matusadona National Park Day 01: Victoria Falls On arrival in Victoria Falls you are being met by a representative of Victoria Falls River Lodge for your road transfer to the lodge, which takes about 20 minutes. On arrival we have planned in for a late lunch for you at the camp. In the later afternoon, you may like to enjoy a sunset cruise on the majestic Zambezi River, which is included in your arrangement with the lodge. Victoria Falls River Lodge L,D Day 02: Victoria Falls Enjoy one full day in this beautiful setting. We have organised for a privately guided tour of the Falls for you, which takes about two hours. One of the seven natural wonders of the world the Victoria Falls is a truly spectacular sight. On your privately guided tour of the Zimbabwe side of the Falls you have the opportunity, to experience its awesome unspoilt grandeur as your guide explains how this 150-million-year-old phenomenon was created. Start at Livingstone's statue and Devil's Cataract and proceed through the rain forest to Danger Point. The walk is approx. 3 km and there are many view points along the way. For the afternoon, you may like to relax or partaking in optional activities offered by the camp. It is also possible to participate in the afternoon game drive of the lodge in the Zambezi National Park, which is also included in your arrangement. -

Thesis Hum 2020 Magadzike B

Rewriting post-colonial historical representations: the case of refugees in Zimbabwe’s war of liberation Blessed Magadzike Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Historical Studies University of Cape Town 12 July 2019 Supervisor: Associate Professor S. Field Co-Supervisor: Dr. M. Mulaudzi University of Cape Town i The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town DECLARATION I Blessed Magadzike declare that Rewriting Postcolonial Historical Representations: The case of Refugees in Zimbabwe’s war of Liberation is my own work and has not been submitted for any degree or examination in any other university, and that all sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by complete references Blessed Magadzike Signed ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Philippa Magadzike nee Karaaidze and my son Regis Tinomudaishe Magadzike who couldn’t wait to see me to complete this work. I say zororai murugare Vhudzijena nemi Nyati iii ABSTRACT ‘Rewriting postcolonial historical representations: The case of refugees in Zimbabwe’s liberation war’ focuses on the historicisation of the experiences of people who were refugees during Zimbabwe’s liberation war, fought between 1966 and 1980. It uses the narratives of former refugees from Mutasa and Bulilima Districts as a way of capturing their histories of the war period. -

Episodic Breakdown

Epic Safari Destinations 15 x 30’ EPISODIC BREAKDOWN 1. Somalisa Expiditions Camp Upon arrival in Zimbabwe, Kristina Guberman travels to Hwange National Park - renowned for it’s impressive elephant herds. She learns about these gentle giants, encounters cheetah on foot and chances upon a cheetah hunt with her guide, David. 2. Mana Pools & Chitake Spring Kristina travels to the Mana Pools and Chitake Springs with guide Craig van Zyl. They come across mating lions, wild dogs, have close encounters with bull elephants, and canoe just meters away from imposing hippos and crocodiles on the mighty Zambezi River. 3. Victoria Falls Kristina gets to tick off one of her bucket list dreams – the majestic Victoria Falls. Her guide Beano walks her through the history of the falls formation and they encounter some of the wildlife that live in the surrounding area. She zip-lines across the gorge and learns the integral role vultures play in the ecosystem. Kristina gets up close and personal with prehistoric-looking beasts at the croc sanctuary, experiences some of the must-do tourist activities and has her first-ever encounter with endangered black rhino at the Stanley and Livingstone Private Game Reserve. 4. Changa Safari Camp Guided by Sean, Kristina explores the Matusadona National Park where they have incredible on- foot encounters with elephants and lions. Will she keep her cool as she comes face-to-face with one of Africa’s apex predators? Kristina is treated to game-viewing by helicopter, tries her hand at fishing and witnesses lions stalking buffalo. 5. Pamuzinda Safari Lodge Pamuzinda Safari Lodge is only one and a half hours from the capital - Harare. -

Early Post-Release Movements, Prey Preference and Habitat Selection of Reintroduced Cheetah (Acinonyx Jubatus) in Liwonde National Park, Malawi

Early Post-Release Movements, Prey Preference and Habitat Selection of Reintroduced Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) in Liwonde National Park, Malawi by Olivia Sievert Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at Stellenbosch University Department of Conservation Ecology & Entomology, Faculty of AgriSciences Supervisor: Dr. Alison Leslie Co-Supervisor: Dr. Kelly Marnewick Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third-party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Olivia Sievert Date: March 2020 Copyright © 2020 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract Once widespread throughout Africa and southwestern Asia, the cheetah has disappeared from the majority of its historical range, making it Africa’s most endangered large felid. Scenario modelling has demonstrated the survival of the cheetah is highly dependent on protected areas and woodland habitats. Reintroduction into protected areas of recoverable range has the potential to assist in the conservation of the species. However, sizeable knowledge gaps regarding the behavioural ecology of this species within its historical range remain and must be filled to assist in reintroduction success. In 2017, African Parks in partnership with the Malawi Department of National Parks and Wildlife and the Endangered Wildlife Trust reintroduced seven cheetah into Malawi after a 20-year extirpation.