Io: a Global Geologic Map and Its Sulfur Volcanism Compared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Io in the Near Infrared: Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) Results from the Galileo Tlybys in 1999 and 2000 Rosaly M

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 106, NO. El2, PAGES 33,053-33,078, DECEMBER 25, 2001 Io in the near infrared: Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) results from the Galileo tlybys in 1999 and 2000 Rosaly M. C. Lopes,• L. W. Kamp,• S. Dout6,2 W. D. Smythe,• R. W. Carlson,• A. S. McEwen, 3 P. E. Geissler,3 S. W. Kieffer, 4 F. E. Leader, s A. G. Davies, • E. Barbinis,• R. Mehlman,s M. Segura,• J. Shirley,• and L. A. Soderblom6 Abstract. Galileo'sNear-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer(NIMS) observedIo duringthe spacecraft'sthree flybysin October 1999, November 1999, and February 2000. The observations,which are summarizedhere, were used to map the detailed thermal structure of activevolcanic regions and the surfacedistribution of SO2 and to investigatethe origin of a yet unidentified compoundshowing an absorptionfeature at ---1 •m. We present a summaryof the observationsand results,focusing on the distributionof thermal emission and of SO2 deposits.We find high eruption temperatures,consistent with ultramafic volcanism,at Pele. Such temperaturesmay be present at other hot spots,but the hottest areas may be too small for those temperaturesto be detected at the spatial resolutionof our observations.Loki is the site of frequent eruptions,and the low thermal emissionmay representlavas cooling on the caldera'ssurface or the coolingcrust of a lava lake. High- resolutionspectral observations of Emakong caldera show thermal emissionand SO2 within the same pixels,implying that patchesof SO2 frost and patchesof coolinglavas or sulfur flows are presentwithin a few kilometersfrom one another. Thermal maps of Prometheusand Amirani showthat these two hot spotsare characterizedby long lava flows.The thermal profilesof flows at both locationsare consistentwith insulatedflows, with the Amirani flow field havingmore breakoutsof fresh lava along its length. -

Hydrothermal Alteration, Fumarolic Deposits and Fluids from Lastarria Volcanic Complex: a Multidisciplinary Study

Andean Geology 42 (3): 166-196. May, 2016 Andean Geology doi: 10.5027/andgeoV43n2-a02 www.andeangeology.cl Hydrothermal alteration, fumarolic deposits and fluids from Lastarria Volcanic Complex: A multidisciplinary study *Felipe Aguilera1, Susana Layana2, Augusto Rodríguez-Díaz3, Cristóbal González2, Julio Cortés4, Manuel Inostroza2 1 Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Avda. Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile. [email protected] 2 Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias mención Geología, Universidad Católica del Norte, Avda. Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile. [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 3 Instituto de Geofísica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Delegación Coyoacán, 04150 México D.F., México. [email protected] 4 Consultor Independiente, Las Docas 4420, La Serena, Chile. [email protected] * Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTRACT. A multidisciplinary study that includes processing of Landsat ETM+ satellite images, chemistry of gas condensed, mineralogy and chemistry of fumarolic deposits, and fluid inclusion data from native sulphur deposits, has been carried out in the Lastarria Volcanic Complex (LVC) with the objective to determine the distribution and charac- teristics of hydrothermal alteration zones and to establish the relations between gas chemistry and fumarolic deposits. Satellite image processing shows the presence of four hydrothermal alteration zones, characterized by a mineral -

Mineralogy, Fluid Inclusion, and Stable Isotope Studies of the Hog Heaven Mining District, Flathead County, Montana

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Spring 2020 MINERALOGY, FLUID INCLUSION, AND STABLE ISOTOPE STUDIES OF THE HOG HEAVEN MINING DISTRICT, FLATHEAD COUNTY, MONTANA Ian Kallio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Geological Engineering Commons MINERALOGY, FLUID INCLUSION, AND STABLE ISOTOPE STUDIES OF THE HOG HEAVEN MINING DISTRICT, FLATHEAD COUNTY, MONTANA by Ian Kallio A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Geoscience Geology Option Montana Tech 2020 ii Abstract The Hog Heaven mining district in northwestern Montana is unique in that it is a high- sulfidation epithermal system containing high Ag-Pb-Zn relative to Au-Cu, with a very high Ag to Au ratio (2,330:1). The deposits are hosted within the Cenozoic Hog Heaven volcanic field (HHVF), a 30 to 36 Ma suite that consists predominantly of rhyodacite flow-dome complexes and pyroclastic rocks. The HHVF is underlain by shallow-dipping siliclastic sediments of the Mesoproterozoic Belt Supergroup. These sediments are known to host important SEDEX (e.g., Sullivan) and red-bed copper (e.g., Spar Lake, Rock Creek, Montanore) deposits rich in Ag-Pb- Zn-Cu-Ba. The HHVF erupted through and deposited on the Belt strata during a period of Oligocene extension. Outcrops and drill core samples from Hog Heaven show alteration patterns characteristic of volcanic-hosted, high-sulfidation epithermal deposits. Vuggy quartz transitions laterally into quartz-alunite alteration where large sanidine phenocrysts (up to 4 cm) have been replaced by fine-grained, pink alunite, and/or argillic alteration that is marked by an abundance of white kaolinite-dickite clay. -

Cubesats to Support Future Io Exploration

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 1136.pdf CUBESATS TO SUPPORT FUTURE IO EXPLORATION. D. A. Williams1, R. M. C. Lopes2, J. Castillo- Rogez2, and P. Scowen1, 1School of Earth & Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Box 871404, Tempe, AZ 85287 ([email protected]), 2NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA, 91109. Introduction: CubeSats are small satellites built Concept B) A CubeSat released on a descent tra- around standardized subunits measuring 10x10x10 cm jectory directed toward a volcano with an active plume and weighing 1.33 kg (‘1U’), with common configura- - either a persistent plume (e.g., Prometheus) or a larg- tions including 1U, 2U, 3U, and 6U (with 12U and er, more variable plume (e.g., Pele), in which the 24U under development). NASA recently had a pro- spacecraft would contain a mass spectrometer and a posal opportunity called Planetary Science Deep Space dust detector to measure plume gas compositions and Small Satellites Study (PSDS3), requesting concepts to dust particle sizes and compositions. This would be apply CubeSats to support planetary exploration, as similar to the Cassini fly-through of the plumes on ride-along payloads for future planetary missions. In Enceladus. In situ measurement of Io’s volcanic gas this abstract we discuss our proposed mission con- compositions using a mass spectrometer has not been cepts, an investigation of how CubeSats may be uti- attempted before, and a CubeSat can risk a flyby at lized to support future exploration of Jupiter’s volcanic much lower altitude where the gas and dust densities moon, Io. -

Establishing a Holocene Tephrochronology for Western Samoa and Its Implication for the Re-Evaluation of Volcanic Hazards

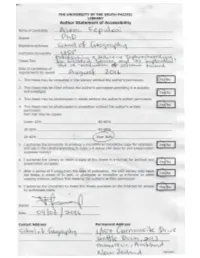

ESTABLISHING A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR WESTERN SAMOA AND ITS IMPLICATION FOR THE RE-EVALUATION OF VOLCANIC HAZARDS by Aleni Fepuleai A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © 2016 by Aleni Fepuleai School of Geography, Earth Science and Environment Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment The University of the South Pacific August 2016 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Aleni Fepuleai, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledge is made in the next. Signature: Date: 01/07/15 Name: Aleni Fepuleai Student ID: s11075361 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mr Aleni Fepuleai. Signature Date: 01/07/15 Name: Dr Eleanor John Designation: Principal Supervisor ABSTRACT Samoan volcanism is tectonically controlled and is generated by tension-stress activities associated with the sharp bend in the Pacific Plate (Northern Terminus) at the Tonga Trench. The Samoan island chain dominated by a mixture of shield and post-erosional volcanism activities. The closed basin structures of volcanoes such as the Crater Lake Lanoto enable the entrapment and retention of a near-complete sedimentary record, itself recording its eruptive history. Crater Lanoto is characterised as a compound monogenetic and short-term volcano. A high proportion of primary tephra components were found in a core extracted from Crater Lake Lanoto show that Crater Lanoto erupted four times (tephra bed-1, 2, 3, and 4). -

The Pulse of the Volcano: Discovery of Episodic Activity at Prometheus on Io

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV (2003) 1455.pdf THE PULSE OF THE VOLCANO: DISCOVERY OF EPISODIC ACTIVITY AT PROMETHEUS ON IO. A. G. Da- vies. Jet Propulsion Laboratory-California Institute of Technology, ms 183-601, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099. (tel: 818-393-1775. email: [email protected]). Introduction: The temporal behaviour of thermal est e-corrected thermal emission during November 1997 output from a volcano yields valuable clues to the pro- (33 GW/µm), more than four times that seen in June cesses taking place at and beneath the surface. Galileo 1996 (orbit G1; see [3]) and Amirani showed its greatest Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) data show thermal emission (up to May 1998) during May 1997 that the ionian volcanoes Prometheus and Amirani (orbit G8), nearly 100 GW/µm, nearly five times that have significant thermal emission in excess of non- seen during orbit G1. Including observations where e > volcanic background emission in every geometrically 60º, Amirani’s maximum observed 5 µm output is 291 appropriate NIMS observation. The 5 µm brightness of GW/µm (May 1998), and the Prometheus maximum is 54 these volcanoes shows considerable variation from GW/µm (May 1998). orbit to orbit. Prometheus in particular exhibits an epi- sodicity that yields valuable constraints to the mecha- x = time between peaks in months nisms of magma supply and eruption. This work is part 60 of an on-going study to chart and quantify the thermal 50 emission of Io’s volcanoes, determine mass eruption 9 rates, and note eruption style. -

Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan

The Icy Moons and the Extended Habitable Zone Europa Interior Models Other Types of Habitable Zones Water requires heat and pressure to remain stable as a liquid Extended Habitable Zones • You do not need sunlight. • You do need liquid water • You do need an energy source. Saturn and its Satellites • Saturn is nearly twice as far from the Sun as Jupiter • Saturn gets ~30% of Jupiter’s sunlight: It is commensurately colder Prometheus • Saturn has 82 known satellites (plus the rings) • 7 major • 27 regular • 4 Trojan • 55 irregular • Others in rings Titan • Titan is nearly as large as Ganymede Titan and the Moons of Saturn Telesto Titan Prometheus Dione Titan Janus Pandora Enceladus Mimas Rhea Pan • . • . Titan The second-largest moon in the Solar System The only moon with a substantial atmosphere 90% N2 + CH4, Ar, C2H6, C3H8, C2H2, HCN, CO2 Equilibrium Temperatures 2 1/4 Recall that TEQ ~ (L*/d ) Planet Distance (au) TEQ (K) Mercury 0.38 400 Venus 0.72 291 Earth 1.00 247 Mars 1.52 200 Jupiter 5.20 108 Saturn 9.53 80 Uranus 19.2 56 Neptune 30.1 45 The Atmosphere of Titan Pressure: 1.5 bars Temperature: 95 K Condensation sequence: • Jovian Moons: H2O ice • Saturnian Moons: NH3, CH4 2NH3 + sunlight è N2 + 3H2 CH4 + sunlight è CH, CH2 Implications of Methane Free CH4 requires replenishment • Liquid methane on the surface? Hazy atmosphere/clouds may suggest methane/ ethane precipitation. The freezing points of CH4 and C2H6 are 91 and 92K, respectively. (Titan has a mean temperature of 95K) (Liquid natural gas anyone?) This atmosphere may resemble the primordial terrestrial atmosphere. -

Appendix 1: Io's Hot Spots Rosaly M

Appendix 1: Io's hot spots Rosaly M. C. Lopes,Jani Radebaugh,Melissa Meiner,Jason Perry,and Franck Marchis Detections of plumes and hot spots by Galileo, Voyager, HST, and ground-based observations. Notes and sources . (N) NICMOS hot spots detected by Goguen etal . (1998). (D) Hot spots detected by C. Dumas etal . in 1997 and/or 1998 (pers. commun.). Keck are hot spots detected by de Pater etal . (2004) and Marchis etal . (2001) from the Keck telescope using Adaptive Optics. (V, G, C) indicate Voyager, Galileo,orCassini detection. Other ground-based hot spots detected by Spencer etal . (1997a). Galileo PPR detections from Spencer etal . (2000) and Rathbun etal . (2004). Galileo SSIdetections of hot spots, plumes, and surface changes from McEwen etal . (1998, 2000), Geissler etal . (1999, 2004), Kezthelyi etal. (2001), and Turtle etal . (2004). Galileo NIMS detections prior to orbit C30 from Lopes-Gautier etal . (1997, 1999, 2000), Lopes etal . (2001, 2004), and Williams etal . (2004). Locations of surface features are approximate center of caldera or feature. References de Pater, I., F. Marchis, B. A. Macintosh, H. G. Rose, D. Le Mignant, J. R. Graham, and A. G. Davies. 2004. Keck AO observations of Io in and out of eclipse. Icarus, 169, 250±263. 308 Appendix 1: Io's hot spots Goguen, J., A. Lubenow, and A. Storrs. 1998. HST NICMOS images of Io in Jupiter's shadow. Bull. Am. Astron. Assoc., 30, 1120. Geissler, P. E., A. S. McEwen, L. Keszthelyi, R. Lopes-Gautier, J. Granahan, and D. P. Simonelli. 1999. Global color variations on Io. Icarus, 140(2), 265±281. -

Trace Elements and Minerals in Fumarolic Sulfur: the Case of Ebeko Volcano, Kuriles

Hindawi Geofluids Volume 2018, Article ID 4586363, 16 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4586363 Research Article Trace Elements and Minerals in Fumarolic Sulfur: The Case of Ebeko Volcano, Kuriles E. P. Shevko,1 S. B. Bortnikova,2 N. A. Abrosimova,2 V. S. Kamenetsky ,3,4 S. P. Bortnikova,2 G. L. Panin,2 and M. Zelenski 3 1 Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy, SBRAS, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia 2Trofmuk Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics, SBRAS, No. 3, Novosibirsk 630090, Russia 3Institute of Experimental Mineralogy RAS, Chernogolovka 142432, Russia 4EarthSciencesandCODES,UniversityofTasmania,PrivateBag79,Hobart,TAS7001,Australia Correspondence should be addressed to M. Zelenski; [email protected] Received 25 June 2017; Revised 13 October 2017; Accepted 14 December 2017; Published 20 March 2018 Academic Editor: Joerg Goettlicher Copyright © 2018 E. P. Shevko et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Native sulfur deposits on fumarolic felds at Ebeko volcano (Northern Kuriles, Russia) are enriched in chalcophile elements (As- Sb-Se-Te-Hg-Cu) and contain rare heavy metal sulfdes (Ag2S, HgS, and CuS), native metal alloys (Au2Pd), and some other low- solubility minerals (CaWO4, BaSO4). Sulfur incrustations are impregnated with numerous particles of fresh and altered andesite groundmass and phenocrysts (pyroxene, magnetite) as well as secondary minerals, such as opal, alunite, and abundant octahedral pyrite crystals. Te comparison of elemental abundances in sulfur and unaltered rocks (andesite) demonstrated that rock-forming elements (Ca, K, Fe, Mn, and Ti) and other lithophile and chalcophile elements are mainly transported by fumarolic gas as aerosol particles, whereas semimetals (As, Sb, Se, and Te), halogens (Br and I), and Hg are likely transported as volatile species, even ∘ at temperatures slightly above 100 C. -

The Natural Choice for Wildlife Holidays Welcome

HOLIDAYS WITH 100% FINANCIAL PROTECTION The natural choice for wildlife holidays Welcome After spending considerable time and effort reflecting, questioning what we do and how we do it, and scrutinising the processes within our office and the systems we use for support, I am delighted to say that we are imbued with a new vigour, undiminished enthusiasm, and greater optimism than ever. My own determination to continue building on the solid foundation of twenty years of experience in wildlife tourism, since we started from very humble beginnings – to offer what is simply the finest selection of high quality, good value, tailor-made wildlife holidays – remains undaunted, and is very much at the core of all we do. A physical move to high-tech office premises in the attractive city of Winchester leaves us much better connected to, and more closely integrated with, the outside world, and thus better able to receive visitors. Our team is leaner, tighter, more widely travelled and more knowledgeable than ever before, allowing us to focus on terrestrial, marine and – along with Dive Worldwide – submarine life without distraction. In planning this brochure we deliberately set out to whet the appetite, and make no mention of either dates or prices. As the vast majority of trips are tailored to our clients’ exact requirements – whether in terms of itinerary, duration, standard of accommodation or price – the itineraries herein serve merely as indications of what is possible. Thereafter, you can refine these suggestions in discussion with one of our experienced consultants to pin down your precise needs and wants, so we can together create the wildlife holiday of your dreams. -

THE IO VOLCANO OBSERVER (IVO) for DISCOVERY 2015. A. S. Mcewen1, E. P. Turtle2, and the IVO Team*, 1LPL, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ USA

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 1627.pdf THE IO VOLCANO OBSERVER (IVO) FOR DISCOVERY 2015. A. S. McEwen1, E. P. Turtle2, and the IVO team*, 1LPL, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ USA. 2JHU/APL, Laurel, MD USA. Introduction: IVO was first proposed as a NASA Discovery mission in 2010, powered by the Advanced Sterling Radioisotope Generators (ASRGs) to provide a compact spacecraft that points and settles quickly [1]. The 2015 IVO uses advanced lightweight solar arrays and a 1-dimensional pivot to achieve similar observing flexibility during a set of fast (~18 km/s) flybys of Io. The John Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab (APL) leads mission implementation, with heritage from MESSENGER, New Horizons, and the Van Allen Probes. Io, one of four large Galilean moons of Jupiter, is the most geologically active body in the Solar System. The enormous volcanic eruptions, active tectonics, and high heat flow are like those of ancient terrestrial planets and present-day extrasolar planets. IVO uses Figure 1. IVO will distinguish between two basic tidal heating advanced solar array technology capable of providing models, which predict different latitudinal variations in heat ample power even at Jovian distances of 5.5 AU. The flux and volcanic activity. Colors indicate heating rate and hazards of Jupiter’s intense radiation environment temperature. Higher eruption rates lead to more advective are mitigated by a comprehensive approach (mission cooling and thicker solid lids [2]. design, parts selection, shielding). IVO will generate Table 2: IVO Science Experiments spectacular visual data products for public outreach. Experiment Characteristics Narrow-Angle 5 µrad/pixel, 2k × 2k CMOS detector, color imaging Science Objectives: All science objectives from Camera (NAC) (filter wheel + color stripes over detector) in 12 bands from 300 to 1100 nm, framing images for movies of the Io Observer New Frontiers concept recommended dynamic processes and geodesy. -

1783-84 Laki Eruption, Iceland

1783-84 Laki eruption, Iceland Eruption History and Atmospheric Effects Thor Thordarson Faculty of Earth sciences, University of Iceland 12/8/2017 1 Atmospheric Effects of the 1783-84 Laki Eruption in Iceland Outline . Volcano-Climate interactions - background Laki eruption . Eruption history . Sulfur release and aerosol loading . Plume transport and aerosol dispersal . Environmental and climatic effects 12/8/2017. Concluding Remarks 2 Santorini, 1628 BC Tambora, 1815 Etna, 44 BC Lakagígar, 1783 Toba, 71,000 BP Famous Volcanic Eruptions Krakatau, 1883 Pinatubo, 1991 El Chichón, 1982 Agung, 1963 St. Helens, 1980 Major volcanic eruptions of the past 250 years Volcano Year VEI d.v.i/Emax IVI Lakagígar [Laki craters], Iceland 1783 4 2300 0.19 Unknown (El Chichón?) 1809 0.20 Tambora, Sumbawa, Indonesia 1815 7 3000 0.50 Cosiguina, Nicaragua 1835 5 4000 0.11 Askja, Iceland 1875 5 1000 0.01* Krakatau, Indonesia 1883 6 1000 0.12 Okataina [Tarawera], North Island, NZ 1886 5 800 0.04 Santa Maria, Guatemala 1902 6 600 0.05 Ksudach, Kamchatka, Russia 1907 5 500 0.02 Novarupta [Katmai], Alaska, US 1912 6 500 0.15 Agung, Bali, Indonesia 1963 4 800 0.06 Mt. St. Helens, Washington, US 1980 5 500 0.00 El Chichón, Chiapas, Mexico 1982 5 800 0.06 Mt. Pinatubo, Luzon, Philippines 1991 6 1000 — Volcano – Climate Interactions Key to Volcanic Forcing is: SO2 mass loading, eruption duration plume height replenishment aerosol production, residence time 12/8/2017 5 Volcanic Forcing: sulfur dioxide sulfate aerosols SO2 75%H2SO4+ 25%H2O clear sky 1991 Pinatubo aerosols