The National Reading Panel: Five Components of Reading Instruction Frequently Asked Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Fluency? Adapted From: Elish-Piper, L

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY | JERRY L. JOHNS LITERACY CLINIC Raising Readers: Tips for Parents What is Fluency? Adapted from: Elish-Piper, L. (2010). Information and ideas for parents about fluency and vocabulary.Illinois Reading Council Journal, 38(2), 48-49. Reading fluency is the ability to read a text easily. Reading mean that children should read as fast as they possibly can. fluency actually has four parts: accuracy, speed, expression and Rate needs to be combined with accuracy, expression and comprehension. Each part is important, but no single part is comprehension to produce fluent reading. Some schools enough on its own. A fluent reader is able to coordinate all four provide a target rate for students in each grade level, usually as aspects of fluency. the number of correct words read per minute. You may wish to ask your child’s teacher if there is a rate goal used for your Accuracy: Reading words correctly is a key to developing fluency. Children need to be able to read words easily without child’s grade level. Those rate targets are important, but they having to stop and decode them by sounding them out or are not the only goal for fluency. For example, if a child reads breaking them into chunks. When children can accurately and very quickly but does not read with expression or understand easily read the words in a text, they are able to think about what what is read, that child is not reading fluently. they are reading rather than putting all of their effort toward Expression: Expression in fluency refers to the ability to read figuring out the words. -

Essential Strategies for Teaching Phonemic Awareness SECTION

SECTION I Essential Strategies for Teaching Phonemic Awareness hat is phonemic awareness and how does it impact reading? Many early childhood and primary grade teachers wrestle with these questions on a daily W basis. This section presents the research on phonemic awareness and best practices for training students to identify sounds. A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF PHONEMIC AWARENESS Phonemic awareness is the ability to focus on and manipulate phonemes in the spoken word (Ehri, Nunes, Willows, & Schuster, 2001). Phonemes are the smallest units in the spoken language, with English containing approximately 41 phonemes (Ehri & Nunes, 2002). Young students often have difficulties letting go of the letters and just concentrating on the sounds in the spoken word. Yet research indicates that phonemic awareness and letter knowledge are key predictors to students’ success in learning to read (National Reading Panel, 2000). In fact, predictive studies show that when children enter kindergarten with the ability to manipulate phonemes and identify letters, they progress at a faster pace in learning to read (Ehri & Roberts, 2006). An ongoing discussion in the field of literacy is whether phonemic awareness is a conceptual understanding about language or whether it is a skill. According to Phillips and Torgesen (2006), it is both an understanding and a skill. For example, in order to identify the phonemes in [cat], students must understand that there are sounds at the beginning, middle, and end that can be manipulated. Students must also be able to complete phonemic awareness tasks such as the following: • Phoneme isolation: Isolate phonemes; for example, “Tell me the first sound in cat.” • Phoneme identity: Recognize common sounds in different words; for example, “Tell me the same sound in rug, rat, and roll.” 1 2 P ROMOTING L ITERACY D EVE L O P MENT • Phoneme categorization: Identify the word with the odd sound in a sequence; for example, “Which word does not belong in sat, sag, rug?” • Phoneme blending: Combine separate sounds to form a word; for example, [b-a-t] for bat. -

Foundations of Reading: Effective Phonological Awareness Instruction and Progress Monitoring

Foundations of Reading: ß What is phonological awareness? Effective ß Why is phonological awareness Phonological considered to be one of the Awareness foundations of reading? Instruction ß What are some ways to teach and Progress phonological awareness to Monitoring students who are struggling with learning to read? ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Phonological Awareness Instruction and Progress Monitoring 1 Phonological Phonemic Awareness Awareness Survey of Knowledge: Foundations of Reading Letter-Sound Alphabetic Knowledge Principle ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Phonological Awareness Instruction and Progress Monitoring 2 Phonological awareness is understanding that spoken language conveys thoughts in words that are composed of sounds (phonemes) specific to that language. Phonological Awareness Phonological awareness is understanding that: ß Words are composed of separate sounds (phonemes); and ß Phonemes can be blended together to make words, words can be separated into phonemes, and phonemes can be manipulated to make new words. ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Phonological Awareness Instruction and Progress Monitoring 3 Phonemes are the smallest units of sound in spoken words. What Are Phonemes? Phonemic awareness specifically focuses on individual sounds (known as phonemes) in words. / m / / a / / t / 1st phoneme 2nd phoneme 3rd phoneme ©2002 UT System/TEA Effective Phonological Awareness Instruction and Progress Monitoring 4 Phonological Awareness Continuum ALLITERATION ONSETS SENTENCE SYLLABLES AND PHONEMES RHYME SEGMENTATION RIMES Alliteration Segmenting Blending Blending or Producing Blending sentences syllables to segmenting groups of phonemes into into spoken say words or the initial words that words, words segmenting consonant or begin with the segmenting spoken words consonant same initial words into into syllables cluster (onset) sound individual and the vowel phonemes, and and consonant Rhyme manipulating sounds spoken phonemes in Matching the after it (rime) ending sounds spoken words of words Examples Alliteration The dog ran away. -

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction Augustine Literacy Project - Charlotte Marion Idol, Site Coordinator Five Essential Components of Reading Instruction: 1.phonemic awareness 2.phonics 3.fluency 4.vocabulary 5.comprehension http://athome.readinghorizons.com/ Importance of Decoding skills: In many schools, 1st and 2nd grade instruction focuses on FVC instead of PA and P.(decoding) For our students, the holes in the foundation tend to be in PA and P. Please prioritize setting a firm foundation! For 1st month of tutoring, don’t worry about weaving in FVC instruction. Fluency/Vocabulary/Comprehension Instruction: What does it look like for 1st/2nd graders? How do I weave this instruction into each lesson? What are fun supplemental activities for “TAKE a BREAK” sessions? Fluency: ALP Manual: Tab 5, pp. 174-178 The ability to read text accurately and quickly. Scored as words read correctly per minute. ONLY DECODABLE TEXT! Easy independent reading level (95% success) Requires repeated ORAL reading practice with a partner providing modeling, feedback, and assistance Includes PROSODY: appropriate expression, inflection, pacing Activities to Promote Fluency Each session: You will already be doing repeated oral reading practice in lesson parts 3-5, 9 To add fun and prosody practice, when student rereads sentences in part 5, play “Roll Punctuation” or “Roll a Face.” Parts 3-5, 9. Handout B. Fluency “Take a Break” session activities: Paired Reading: Reading aloud along with your student to promote correct pacing, inflection, expression https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5RJyUnAkWM Punctuation Punch: Periods, commas, question marks, exclamation point. Fun AVK stimulation! Use book Yo! Yes! to teach this technique. -

Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers

Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice - 12(4) • Autumn • 2822-2828 ©2012 Educational Consultancy and Research Center www.edam.com.tr/estp Comparing the Word Processing and Reading Comprehension of Skilled and Less Skilled Readers İ. Birkan GULDENOĞLU Tevhide KARGINa Paul MILLER Ankara University Ankara University University of Haifa Abstract The purpose of this study was to compare the word processing and reading comprehension skilled in and less skilled readers. Forty-nine, 2nd graders (26 skilled and 23 less skilled readers) partici- pated in this study. They were tested with two experiments assessing their processing of isolated real word and pseudoword pairs as well as their reading comprehension skills. Findings suggest that there is a significant difference between skilled and less skilled readers both with regard to their word processing skills and their reading comprehension skills. In addition, findings suggest that word processing skills and reading comprehension skills correlate positively both skilled and less skilled readers. Key Words Reading, Reading Comprehension, Word Processing Skills, Reading Theories. Reading is one of the most central aims of school- According to the above mentioned phonologi- ing and all children are expected to acquire this cal reading theory, readers first recognize written skill in school (Güzel, 1998; Moates, 2000). The words phonologically via their spoken lexicon and, ability to read is assumed to rely on two psycho- subsequently, apply their linguistic (syntactic, se- linguistic processes: -

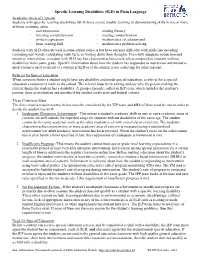

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language Academic Areas of Concern Students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) have severe trouble learning or demonstrating skills in one or more of these academic areas: oral expression reading fluency listening comprehension reading comprehension written expression mathematics calculation and basic reading skill mathematics problem solving Students with SLD often do well in some school subjects but have extreme difficulty with skills like decoding (sounding out) words, calculating math facts, or writing down their thoughts. Even with adequate instruction and intensive intervention, a student with SLD has low classroom achievement when compared to students without disabilities in the same grade. Specific information about how the student has responded to instruction and intensive intervention is used to decide if a student is SLD or if the student is not achieving for other reasons. Referral for Special Education When someone thinks a student might have any disability and needs special education, a referral for a special education evaluation is made to the school. The referral must be in writing and say why the person making the referral thinks the student has a disability. A group of people, called an IEP team, which includes the student’s parents, does an evaluation and decides if the student meets state and federal criteria. Three Criteria to Meet The three criteria (requirements) below must be considered by the IEP team and all 3 of them must be met in order to decide the student has SLD. 1. Inadequate Classroom Achievement - This means a student's academic skills in one or more academic areas of concern are well outside the expected range for students without disabilities of the same age. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

Vocabulary and Phonological Awareness in 3- to 4-Year-Old Children: Effects of a Training Program

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2010 Vocabulary and Phonological Awareness in 3- to 4-Year-Old Children: Effects of a Training Program Iuliana Elena Baciu Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Child Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Baciu, Iuliana Elena, "Vocabulary and Phonological Awareness in 3- to 4-Year-Old Children: Effects of a Training Program" (2010). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1108. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1108 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Library and Archives Biblioth&que et, 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68757-4 Our file Notre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-68757-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliothdque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

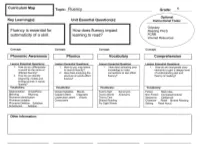

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

A Bad Case of Stripes

A Bad Case of Stripes A Bad Case of Stripes Author: David Shannon Publisher: Scholastic Paperbacks (2004) Binding: Paperback, 32 pages Item Call Number: E SHANN Camilla Cream loves lima beans, but she never eats them. Why? Because the other kids in her school don't like them. And Camilla is very, very worried about what other people think of her. In fact, she’s so worried that she's about to break out in a bad case of stripes! Questions to talk about with your child: Why did Camilla break out in stripes (and other patterns?) What did you notice about the patterns that break out on Camilla? Do they have anything to do with what’s happening around her? Look at each of the pictures. Was there anything about Camilla that stayed the same each time she changed? What made Camilla finally turn back into herself? Did Camilla learn anything from having a bad case of stripes? Look at the last page. Was there anything different about the way Camilla looks? Fun things to do together: David Shannon always hides a picture of his white terrier Fergus somewhere in each of his books. Look for the picture of Fergus in this book. Camilla loves lima beans. Have lima beans for lunch or dinner one day. Draw a picture of yourself with stripes, polka dots or some other pattern. Check out a book about patterns, for example, Pattern Bugs by Trudi Harris or Patterns at the Museum by Tracey Steffora. Recognizing and completing simple patterns is an important kindergarten readiness skill. -

Research and the Reading Wars James S

CHAPTER 4 Research and the Reading Wars James S. Kim Controversy over the role of phonics in reading instruction has persisted for over 100 years, making the reading wars seem like an inevitable fact of American history. In the mid-nineteenth century, Horace Mann, the secre- tary of the Massachusetts Board of Education, railed against the teaching of the alphabetic code—the idea that letters represented sounds—as an imped- iment to reading for meaning. Mann excoriated the letters of the alphabet as “bloodless, ghostly apparitions,” and argued that children should first learn to read whole words) The 1886 publication of James Cattell’s pioneer- ing eye movement study showed that adults perceived words more rapidly 2 than letters, providing an ostensibly scientific basis for Mann’s assertions. In the twentieth century, state education officials like Mann have contin- ued to voice strong opinions about reading policy and practice, aiding the rapid implementation of whole language—inspired curriculum frameworks and texts during the late 1980s. And scientists like Cattell have shed light on theprocesses underlying skillful reading, contributing to a growing scientific 3 consensus that culminated in the 2000 National Reading Panel report. This chapter traces the history of the reading wars in both the political arena and the scientific community. The narrative is organized into three sections. The first offers the history of reading research in the 1950s, when the “conventional wisdom” in reading was established by acclaimed lead- ers in the field like William Gray, who encouraged teachers to instruct chil- dren how to read whole words while avoiding isolated phonics drills. -

Phonemic Awareness and the Teaching of Reading

PHONEMIC AWARENESS and the Teaching of Reading A Position Statement from the Board of Directors of the International Reading Association Much has been written regarding phonemic awareness, phonics, and the failure of schools to teach the basic skills of reading. The Board of Directors offers this position paper in the hope of clarifying some of these issues as they relate to research, policy, and practice. We view research and theory as a resource for educators to make informed instructional decisions. We must use research wisely and be mindful of its limitations and its potential to inform instruction. Why the What is phonemic sudden interest in Isn’t phonemic awareness? phonemic awareness? awareness just a 1990s word for There is no single definition of phonemic The findings regarding phonemic aware- awareness. The term has gained popularity ness are not as new to the field of literacy phonics? in the 1990s as researchers have attempted as some may think, although it is only in to study early-literacy development and recent years that they have gained wide Phonemic awareness is not phonics. reading disability. Phonemic awareness is attention. For over 50 years discussions Phonemic awareness is an understanding typically described as an insight about have continued regarding the relation about spoken language. Children who are oral language and in particular about the between a child’s awareness of the sounds phonemically aware can tell the teacher segmentation of sounds that are used in of spoken words and his or her ability to that bat is the word the teacher is repre- speech communication.