Jazz and Caribbean Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014-2015 Fine Arts Mid-Season Brochure

Deana Martin Photo credit: Pat Lambert The Fab Four NORTH CENTRAL COLLEGE Russian National SEASON Ballet Theatre 2015 WINTER/SPRING Natalie Cole Robert Irvine 630-637-SHOW (7469) | 3 | JA NUARY 2015 Event Price Page # January 8, 9, 10, 11 “October Mourning” $10, $8 4 North Central College January 16 An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis $20, $15 4 January 18 Chicago Sinfonietta “Annual Tribute to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” $58, $46 4 January 24 27th Annual Gospel Extravaganza $15, $10 4 Friends of the Arts January 24 Jim Peterik & World Stage $60, $50 4 January 25 Janis Siegel “Nightsongs” $35, $30 4 Thanks to our many contributors, world-renowned artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, the Chicago FEbrUARY 2015 Event Price Page # Symphony Orchestra, Vienna Boys Choir, Wynton Marsalis, Celtic Woman and many more have February 5, 6, 7 “True West” $5, $3 5 performed in our venues. But the cost of performance tickets only covers half our expenses to February 6, 7 DuPage Symphony Orchestra “Gallic Glory” $35 - $12 5 February 7 Natalie Cole $95, $85, $75 5 bring these great artists to the College’s stages. The generous support from the Friends of the February 13 An Evening with Jazz Vocalist Janice Borla $20, $15 5 Arts ensures the College can continue to bring world-class performers to our world-class venues. February 14 Blues at the Crossroads $65, $50 5 February 21 Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn $65, $50 6 northcentralcollege.edu/shows February 22 Robin Spielberg $35, $30 6 Join Friends of the Arts today and receive exclusive benefits. -

I the Use of African Music in Jazz from 1926-1964: an Investigation of the Life

The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston by Jason John Squinobal Batchelor of Music, Berklee College of Music, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2007 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jason John Squinobal It was defended on April 17, 2007 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department Dr. Akin Euba, Professor, Music Department Dr. Eric Moe, Professor, Music Department Thesis Director: Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department ii Copyright © by Jason John Squinobal 2007 iii The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston Jason John Squinobal, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2007 ABSTRACT There have been many jazz musicians who have utilized traditional African music in their music. Randy Weston was not the first musician to do so, however he was chosen for this thesis because his experiences, influences, and music clearly demonstrate the importance traditional African culture has played in his life. Randy Weston was born during the Harlem Renaissance. His parents, who lived in Brooklyn at that time, were influenced by the political views that predominated African American culture. Weston’s father, in particular, felt a strong connection to his African heritage and instilled the concept of pan-Africanism and the writings of Marcus Garvey firmly into Randy Weston’s consciousness. -

Ellingtonia a Publication of the Duke Ellington Society, Inc

Ellingtonia A Publication Of The Duke Ellington Society, Inc. Volume XXIV, Number 3 March 2016 William McFadden, Editor Copyright © 2016 by The Duke Ellington Society, Inc., P.O. Box 29470, Washington, D.C. 20017, U.S.A. Web Site: depanorama.net/desociety E-mail: [email protected] This Saturday Night . ‘Hero of the Newport Jazz Festival’. Paul Gonsalves Our March meeting will May 19-23, 2016 New York City bring in the month just like the proverbial lion in Sponsored by The Duke Ellington Center a program selected by Art for the Arts (DECFA) Luby. It promises a Tentative Schedule Announced finely-tuned revisit to some of the greatest tenor Thursday, May 19, 2016 saxophone virtuosity by St. Peter’s Church, 619 Lexington Ave. Paul Gonsalves, other 12:30 - 1:45 Jazz on the Plaza—The Music of Duke than his immortal 16-bar solo on “Diminuendo and Ellington, East 53rd St. and Lexington Ave. at St. Peter’s Crescendo in Blue” at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956. That’s a lot of territory, considering Paul’s quar- 3:00 - 5:30 “A Drum Is A Woman” - Screenings at The ter century with The Orchestra. In addition to his ex- Paley Center for Media, 25 West 52nd St. pertise on things Gonsalves, Art’s inspiration for this 5:30 - 7:00 Dinner break program comes from a memorable evening a decade ago where the same terrain was visited and expertly 7:15 - 8:00 Gala Opening Reception at St. Peter’s, hosted by the late Ted Shell. “The Jazz Church” - Greetings and welcome from Mercedes Art’s blues-and-ballads-filled listen to the man called Ellington, Michael Dinwiddie (DEFCA) and Ray Carman “Strolling Violins” will get going in our regular digs at (TDES, Inc.) Grace Lutheran Church, 4300—16th Street (at Varnum St.), NW, Washington, DC 20011 on: 8:00 - 9:00 The Duke Ellington Center Big Band - Frank Owens, Musical Director Saturday, 5 March 2016—7:00 PM. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

Django Reinhardt

Data » Personalities » Django Reinhardt http://romani.uni-graz.at/rombase Django Reinhardt Peter Wagner Today is the 1st of November, 1928, All Saint’s Day, late in the evening. The Reinhardt family shares this holiday with the souls of the deceased, particularly with a young one, only lately deceased, for whom the caravan has been decorated with artificial flowers. Young Django Reinhardt is returning from a concert, most probably preoccupied by an offer by Jack Holton, the English master of symphonic jazz, to move to him to England and play in his orchestra. Fate, however, had decreed otherwise. He lights the candles, and with them the flowers, and immediately the whole caravan catches fire; the family is glad to escape with their lives. For the young, promising musician, this incident is a catastrophe. His left leg is badly burnt, it will later have to be operated on, but what is worse, two fingers of his left hand remain unable to function, which is to lose the basis of existence for a goldsmith or a musician. But not Django Reinhardt. A fanatic love of music had already rooted in him, and a present – a guitar which should support his therapy – makes it break out. Notwithstanding his handicap, an inner need to express himself via music makes him return in all his virtuosity within one and a half years, equipped with additional, original means of expression. His new technique arouses amazement and curiosity with a whole generation of guitarists and musical researchers. It is difficult to judge the role of his handicap in this still significant– mainly among the Roma – school. -

JREV3.8FULL.Pdf

JAZZ WRITING? I am one of Mr. Turley's "few people" who follow The New Yorker and are jazz lovers, and I find in Whitney Bal- liett's writing some of the sharpest and best jazz criticism in the field. He has not been duped with "funk" in its pseudo-gospel hard-boppish world, or- with the banal playing and writing of some of the "cool school" Californians. He does believe, and rightly so, that a fine jazz performance erases the bound• aries of jazz "movements" or fads. He seems to be able to spot insincerity in any phalanx of jazz musicians. And he has yet to be blinded by the name of a "great"; his recent column on Bil- lie Holiday is the most clear-headed analysis I have seen, free of the fan- magazine hero-worship which seems to have been the order of the day in the trade. It is true that a great singer has passed away, but it does the late Miss Holiday's reputation no good not to ad• LETTERS mit that some of her later efforts were (dare I say it?) not up to her earlier work in quality. But I digress. In Mr. Balliett's case, his ability as a critic is added to his admitted "skill with words" (Turley). He is making a sincere effort to write rather than play jazz; to improvise with words,, rather than notes. A jazz fan, in order to "dig" a given solo, unwittingly knows a little about the equipment: the tune being improvised to, the chord struc• ture, the mechanics of the instrument, etc. -

An Anthropological Exploration of the Effects of Family Cash Transfers On

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF FAMILY CASH TRANSFERS ON THE DIETS OF MOTHERS AND CHILDREN IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Ana Carolina Barbosa de Lima Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University July, 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Eduardo S. Brondízio, PhD ________________________________ Catherine Tucker, PhD ________________________________ Darna L. Dufour, PhD ________________________________ Richard R. Wilk, PhD ________________________________ Stacey Giroux Wells, PhD Date of Defense: April 14th, 2017. ii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my research committee. I have immense gratitude and admiration for my main adviser, Eduardo Brondízio, who has been present and supportive throughout the development of this dissertation as a mentor, critic, reviewer, and friend. Richard Wilk has been a source of inspiration and encouragement since the first stages of this work, someone who never doubted my academic capacity and improvement. Darna Dufour generously received me in her lab upon my arrival from fieldwork, giving precious advice on writing, and much needed expert guidance during a long year of dietary and anthropometric data entry and analysis. Catherine Tucker was on board and excited with my research from the very beginning, and carefully reviewed the original manuscript. Stacey Giroux shared her experience in our many meetings in the IU Center for Survey Research, and provided rigorous feedback. I feel privileged to have worked with this set of brilliant and committed academics. -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

Celebrating Our Calypso Monarchs 1939- 1980

Celebrating our Calypso Monarchs 1939-1980 T&T History through the eyes of Calypso Early History Trinidad and Tobago as most other Caribbean islands, was colonized by the Europeans. What makes Trinidad’s colonial past unique is that it was colonized by the Spanish and later by the English, with Tobago being occupied by the Dutch, Britain and France several times. Eventually there was a large influx of French immigrants into Trinidad creating a heavy French influence. As a result, the earliest calypso songs were not sung in English but in French-Creole, sometimes called patois. African slaves were brought to Trinidad to work on the sugar plantations and were forbidden to communicate with one another. As a result, they began to sing songs that originated from West African Griot tradition, kaiso (West African kaito), as well as from drumming and stick-fighting songs. The song lyrics were used to make fun of the upper class and the slave owners, and the rhythms of calypso centered on the African drum, which rival groups used to beat out rhythms. Calypso tunes were sung during competitions each year at Carnival, led by chantwells. These characters led masquerade bands in call and response singing. The chantwells eventually became known as calypsonians, and the first calypso record was produced in 1914 by Lovey’s String Band. Calypso music began to move away from the call and response method to more of a ballad style and the lyrics were used to make sometimes humorous, sometimes stinging, social and political commentaries. During the mid and late 1930’s several standout figures in calypso emerged such as Atilla the Hun, Roaring Lion, and Lord Invader and calypso music moved onto the international scene. -

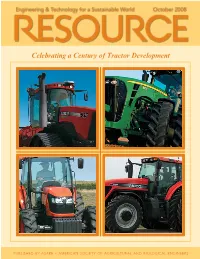

Resource Magazine October 2008 Engineering and Technology for A

Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development PUBLISHED BY ASABE – AMERICAN SOCIETY OF AGRICULTURAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERS Targeted access to 9,000 international agricultural & biological engineers Ray Goodwin (800) 369-6220, ext. 3459 BIOH0308Filler.indd 1 7/24/08 9:15:05 PM FEATURES COVER STORY 5 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development Carroll Goering Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Plowing down memory lane: a top-six list of tractor changes over the last century with emphasis on those that transformed agriculture. Vol. 15, No. 7, ISSN 1076-3333 7 Adding Value to Poultry Litter Using ASABE President Jim Dooley, Forest Concepts, LLC Transportable Pyrolysis ASABE Executive Director M. Melissa Moore Foster A. Agblevor ASABE Staff “This technology will not only solve waste disposal and water pollution Publisher Donna Hull problems, it will also convert a potential waste to high-value products such as Managing Editor Sue Mitrovich energy and fertilizer.” Consultants Listings Sandy Rutter Professional Opportunities Listings Melissa Miller ENERGY ISSUES, FOURTH IN THE SERIES ASABE Editorial Board Chair Suranjan Panigrahi, North Dakota State University 9 Renewable Energy Gains Global Momentum Secretary/Vice Chair Rafael Garcia, USDA-ARS James R. Fischer, Gale A. Buchanan, Ray Orbach, Reno L. Harnish III, Past Chair Edward Martin, University of Arizona and Puru Jena Board Members Wayne Coates, University of Arizona; WIREC 2008 brought together world leaders in the fi eld of renewable energy Jeremiah Davis, Mississippi State University; from 125 countries to address the market adoption and scale-up of renewable Donald Edwards, retired; Mark Riley, University of Arizona; Brian Steward, Iowa State University; energy technologies.