The Lattice-Boltzmann Method for Multiphase Fluid Flow Simulations and Euler-Lagrange Large-Eddy Simulations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiscale Computational Fluid Dynamics

energies Review Multiscale Computational Fluid Dynamics Dimitris Drikakis 1,*, Michael Frank 2 and Gavin Tabor 3 1 Defence and Security Research Institute, University of Nicosia, Nicosia CY-2417, Cyprus 2 Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow G1 1UX, UK 3 CEMPS, University of Exeter, Harrison Building, North Park Road, Exeter EX4 4QF, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 3 July 2019; Accepted: 16 August 2019; Published: 25 August 2019 Abstract: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has numerous applications in the field of energy research, in modelling the basic physics of combustion, multiphase flow and heat transfer; and in the simulation of mechanical devices such as turbines, wind wave and tidal devices, and other devices for energy generation. With the constant increase in available computing power, the fidelity and accuracy of CFD simulations have constantly improved, and the technique is now an integral part of research and development. In the past few years, the development of multiscale methods has emerged as a topic of intensive research. The variable scales may be associated with scales of turbulence, or other physical processes which operate across a range of different scales, and often lead to spatial and temporal scales crossing the boundaries of continuum and molecular mechanics. In this paper, we present a short review of multiscale CFD frameworks with potential applications to energy problems. Keywords: multiscale; CFD; energy; turbulence; continuum fluids; molecular fluids; heat transfer 1. Introduction Almost all engineered objects are immersed in either air or water (or both), or make use of some working fluid in their operation. -

Multiphase Turbulence in Bubbly Flows: RANS Simulations

This is a repository copy of Multiphase turbulence in bubbly flows: RANS simulations. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90676/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Colombo, M and Fairweather, M (2015) Multiphase turbulence in bubbly flows: RANS simulations. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 77. 222 - 243. ISSN 0301-9322 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2015.09.003 © 2015. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Multiphase turbulence in bubbly flows: RANS simulations 2 3 Marco Colombo* and Michael Fairweather 4 Institute of Particle Science and Engineering, School of Chemical and Process Engineering, 5 University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom 6 E-mail addresses: [email protected] (Marco Colombo); [email protected] 7 (Michael Fairweather) 8 *Corresponding Author: +44 (0) 113 343 2351 9 10 Abstract 11 12 The ability of a two-fluid Eulerian-Eulerian computational multiphase fluid dynamic model to 13 predict bubbly air-water flows is studied. -

Convective Boiling Heat Transfer and Two-Phase Flow Characteristics

International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 46 (2003) 4779–4788 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijhmt Convective boiling heat transfer and two-phase flow characteristics inside a small horizontal helically coiled tubing once-through steam generator Liang Zhao, Liejin Guo *, Bofeng Bai, Yucheng Hou, Ximin Zhang State Key Laboratory of Multiphase Flow in Power Engineering, XiÕan Jiaotong University, Xi’an Shaanxi 710049, China Received 15 February 2003; received in revised form 8 June 2003 Abstract The pressure drop and boiling heat transfer characteristics of steam-water two-phase flow were studied in a small horizontal helically coiled tubing once-through steam generator. The generator was constructed of a 9-mm ID 1Cr18Ni9Ti stainless steel tube with 292-mm coil diameter and 30-mm pitch. Experiments were performed in a range of steam qualities up to 0.95, system pressure 0.5–3.5 MPa, mass flux 236–943 kg/m2s and heat flux 0–900 kW/m2. A new two-phase frictional pressure drop correlation was obtained from the experimental data using ChisholmÕs B-coefficient method. The boiling heat transfer was found to be dependent on both of mass flux and heat flux. This implies that both the nucleation mechanism and the convection mechanism have the same importance to forced convective boiling heat transfer in a small horizontal helically coiled tube over the full range of steam qualities (pre-critical heat flux qualities of 0.1–0.9), which is different from the situations in larger helically coiled tube where the convection mechanism dominates at qualities typically >0.1. Traditional single parameter Lockhart–Martinelli type correlations failed to satisfactorily correlate present experimental data, and in this paper a new flow boiling heat transfer correlation was proposed to better correlate the experimental data. -

Experimental Research of Multiphase Flow with Cavitation in the Nozzle

EPJ Web of Conferences 114, 02 058 (2016 ) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201611004 2 58 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2016 Experimental research of multiphase flow with cavitation in the nozzle Milada Kozubkova1, Marian Bojko1, Jana Jablonska1, Dorota Homa2,a and Jií T\ma3 1Department of Hydromechanics and Hydraulic Equipment, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, VSB – Technical University of Ostrava, 17. listopadu 15, 708 33 Ostrava, Czech Republic 2Institute of Power Engineering and Turbomachinery, Faculty of Energy and Environmental Engineering, Silesian University of Technology, Konarskiego Street 18, 44 100 Gliwice, Poland 3Department of Controls Systems and Instrumentations, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, VSB – Technical University of Ostrava, 17. listopadu 15, 708 33 Ostrava, Czech Republic Abstract. The paper deals with the problems of cavitation in water flow in the nozzle. The area of research is divided into two directions (experimental and numerical research). During the experimental research the equipment with the nozzle is under the measurement and basic physical quantities such as pressure and volume flow rate are recorded. In the following phase measuring of noise which is generated during flow through the nozzle in the area of cavitation is measured at various operating conditions of the pump. In the second part the appropriate multiphase mathematical model including the consideration of cavitation is defined. Boundary conditions for numerical simulation are defined on the basis of experimental measurements. Undissolved air in the flow is taken into account to obtain pressure distribution in accordance to measured one. Results of the numerical simulation are presented by means of basic current quantities such as pressure, velocity and volume fractions of each phase. -

Introduction

On the use of Darcy's law and invasion‐percolation approaches for modeling large‐scale geologic carbon sequestration Curtis M. Oldenburg Sumit Mukhopadhyay Abdullah Cihan First published: 01 December 2015 https://doi.org/10.1002/ghg.1564 Cited by: 4 UC-eLinks Abstract Most large‐scale flow and transport simulations for geologic carbon sequestration (GCS) applications are carried out using simulators that solve flow equations arising from Darcy's law. Recently, the computational advantages of invasion‐percolation (IP) modeling approaches have been presented. We show that both the Darcy's‐law‐ and the gravity‐capillary balance solved by IP approaches can be derived from the same multiphase continuum momentum equation. More specifically, Darcy's law arises from assuming creeping flow with no viscous momentum transfer to stationary solid grains, while it is assumed in the IP approach that gravity and capillarity are the dominant driving forces in a quasi‐static two‐phase (or more) system. There is a long history of use of Darcy's law for large‐scale GCS simulation. However, simulations based on Darcy's law commonly include significant numerical dispersion as users employ large grid blocks to keep run times practical. In contrast, the computational simplicity of IP approaches allows large‐scale models to honor fine‐scale hydrostratigraphic details of the storage formation which makes these IP models suitable for analyzing the impact of small‐scale heterogeneities on flow. However, the lack of time‐dependence in the IP models is a significant disadvantage, while the ability of Darcy's law to simulate a range of flows from single‐phase‐ and pressure‐gradient‐driven flows to buoyant multiphase gravity‐capillary flow is a significant advantage. -

Multiphase Turbulent Flow

Multiphase Turbulent Flow Ken Kiger - UMCP Overview • Multiphase Flow Basics – General Features and Challenges – Characteristics and definitions • Conservation Equations and Modeling Approaches – Fully Resolved – Eulerian-Lagrangian – Eulerian-Eulerian • Averaging & closure – When to use what approach? • Preferential concentration • Examples • Modified instability of a Shear Layer • Sediment suspension in a turbulent channel flow • Numerical simulation example: Mesh-free methods in multiphase flow What is a multiphase flow? • In the broadest sense, it is a flow in which two or more phases of matter are dynamically interacting – Distinguish multiphase and/or multicomponent • Liquid/Gas or Gas/Liquid • Gas/Solid • Liquid/Liquid – Technically, two immiscible liquids are “multi-fluid”, but are often referred to as a “multiphase” flow due to their similarity in behavior Single component Multi-component Water Air Single phase Pure nitrogen H20+oil emulsions Steam bubble in H 0 Coal particles in air Multi-phase 2 Ice slurry Sand particle in H20 Dispersed/Interfacial • Flows are also generally categorized by distribution of the components – “separated” or “interfacial” • both fluids are more or less contiguous throughout the domain – “dispersed” • One of the fluids is dispersed as non- contiguous isolated regions within the other (continuous) phase. • The former is the “dispersed” phase, while the latter is the “carrier” phase. • One can now describe/classify the geometry of the dispersion: • Size & geometry • Volume fraction Gas-Liquid Flow -

Prediction of Multiphase Flow in Pipelines: Literature Review

Ingeniería y Ciencia ISSN:1794-9165 | ISSN-e: 2256-4314 ing. cienc., vol. 11, no. 22, pp. 213–233, julio-diciembre. 2015. http://www.eafit.edu.co/ingciencia This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 by Prediction of Multiphase Flow in Pipelines: Literature Review M. Jerez-Carrizales1, J. E. Jaramillo2 and D. Fuentes3 Received: 06-05-2015 | Accepted: 02-07-2015 | Online: 31-07-2015 MSC:76T10 | PACS:47.55.Ca doi:10.17230/ingciencia.11.22.10 Abstract In this work a review about the most relevant methods found in the lite- rature to model the multiphase flow in pipelines is presented. It includes the traditional simplified and mechanistic models, moreover, principles of the drift flux model and the two fluid model are explained. Even though, it is possible to find several models in the literature, no one is able to re- produce all flow conditions presented in the oil industry. Therefore, some issues reported by different authors related to model validation are here also discussed. Key words: drift flux; two fluid; mechanistic; vertical lift performance; pressure drop 1 Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, [email protected]. 2 Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga,Colombia, [email protected]. 3 Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia, [email protected]. Universidad EAFIT 213| Prediction of Multiphase Flow in Pipelines: Literature Review Predicción del flujo multifásico en tuberías: artículo de revisión Resumen En este trabajo se presenta una revisión de los métodos más relevantes en la industria del petróleo para modelar el flujo multifásico en tuberías. -

Enhancement of Turbulent Convective Heat Transfer Using a Microparticle Multiphase Flow

energies Article Enhancement of Turbulent Convective Heat Transfer using a Microparticle Multiphase Flow Tao Wang 1,2,*, Zengliang Gao 1,* and Weiya Jin 1 1 Institute of Process Equipment and Control Engineering, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou 310032, China; [email protected] 2 Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Quzhou University, Quzhou 324000, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.W.); [email protected] (Z.G.) Received: 12 February 2020; Accepted: 9 March 2020; Published: 10 March 2020 Abstract: The turbulent heat transfer enhancement of microfluid as a heat transfer medium in a tube was investigated. Within the Reynolds number ranging from 7000 to 23,000, heat transfer, friction loss and thermal performance characteristics of graphite, Al2O3 and CuO microfluid with the particle volume fraction of 0.25%–1.0% and particle size of 5 µm have been respectively tested. The results showed that the thermal performance of microfluids was better than water. In addition, the graphite microfluid had the best turbulent convective heat transfer effect among several microfluids. To further investigate the effect of graphite particle size on thermal performance, the heat transfer characteristics of the graphite microfluid with the size of 1 µm was also tested. The results showed that the thermal performance of the particle size of 1 µm was better than that of 5 µm. Within the investigated range, the maximum value of the thermal performance of graphite microfluid was found at a 1.0% volume fraction, a Reynolds number around 7500 and a size of 1 µm. In addition, the simulation results showed that the increase of equivalent thermal conductivity of the microfluid and the turbulent kinetic energy near the tube wall, by adding the microparticles, caused the enhancement of heat transfer; therefore, the microfluid can be potentially used to enhance turbulent convective heat transfer. -

Unsteady Multiphase Modeling of Cavitation Around Naca 0015

Journal of Marine Science and Technology, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 689-696 (2010) 689 UNSTEADY MULTIPHASE MODELING OF CAVITATION AROUND NACA 0015 Abolfazl Asnaghi*, Ebrahim Jahanbakhsh*, and Mohammad Saeed Seif* Key words: cavitation, unsteady flow, numerical simulation, NACA systems like pumps, nozzles and injectors. 0015. Cavitation is categorized by a dimensionless number that called cavitation number, where it depends on the vapor pres- sure, the liquid density, the main flow pressure and the main ABSTRACT flow velocity, respectively. When cavitation number of flow The present study focuses on the numerical simulation of reduces the probability of cavitation formation increases. Usu- cavitation around the NACA 0015. The unsteady behaviors ally the cavitation formation of a flow is categorized based on of cavitation which have worthwhile applications are inves- the cavitation number of the flow. tigated. The cavitation patterns, velocity fields and frequency In a flow over the body, five different cavitation regimes are of the cavitating flow around hydrofoil is obtained. For multi observed: incipient, shear, cloud, partial, and super-cavitation. phase simulation, single-fluid Navier–Stokes equations, along Undesirable aspects of cavitation phenomenon are erosion, with a volume fraction transport equation, are employed. The structural damages, noise and power loss in addition to bene- bubble dynamics model is utilized to simulate phase change. ficial features such as drag reduction and the effects of cavita- SIMPLE algorithm is used for velocity and pressure compu- tion in water jet washing systems. The drag reduction observed tations. For discretization of equations the finite-volume on bodies surrounded fully or partially with cavity strongly approach written in body fitted curvilinear coordinates, on encourages one to research on the cavitating flows. -

Multiphase Flow Production Model

MULTIPHASE FLOW PRODUCTION MODEL THEORY AND USER'S MANUAL DEA 67 PHASE l MAURER ENGINEERING INC. 2916 West T.C. Jester Houston, Texas 77018 Multiphase Flow Production Model (PROMODl) Velocity String Nodal Analysis Gas Lift Theory and User's Manual DEA-67, Phase I Project to Develop And Evnluate Slim-Hole And Coiled-Tubing Technology MAURER ENGINEERING INC. 2916 West T.C. Jester Boulevard Houston, Texas 77018-7098 Telephone: (713) 683-8227 Telex: 216556 Facsimile: (713) 6834418 January 1994 TR94-12 This copyrighted 1994 confidential report and computer program are for the sole use of Participants on the Drilling Engineering Association DEA-67 project to DEVELOP AND EVALUATE SLIM-HOLE AND COILED-TUBING TECHNOLOGY and their affiliates, and are not to be disdosed to other parties. Data output from the program can be disclosed to third parties. Participants and their a~liatesare free to make copies of this report for their own use. Table of Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 1-1 1.1 MODEL FEATURES OF PROMOD ............................. 1-1 1.2 REQUIRED INPUT DATA ................................... 1-2 1.3 DISCLAIMER ........................................... 1-3 1.4 COPYRIGHT ........................................1-3 2. THEORY AND EQUATIONS ...................................2-1 2.1 INTRODUCTION ......................................... 2-1 2.2 SOLUTION PROCEDURE FOR BOITOM-HOLE NODE ............... 2-3 2.3 SOLUTION PROCEDURE FOR WELLHEAD NODE .................. 2-5 2.4 RESERVOIR INFLOW PERFORMANCE EQUATIONS ................ 2-6 2.4.1 PI Equation for Oil Reservoirs ............................ 2-6 2.4.2 Vogel's Equation for Oil Reservoirs ......................... 2-8 2.4.3 Fetkovich's Equation for Gas Reservoirs ...................... 2-8 2.5 MULTIPHASE CORRELATIONS FOR FLOW IN WELLBORE OR SURFACELINES ....................................... -

Lagrangian–Eulerian Methods for Multiphase Flows

Lagrangian–Eulerian methods for multiphase flows Shankar Subramaniam ∗ Department of Mechanical Engineering, Iowa State University Abstract This review article aims to provide a comprehensive and understandable account of the theoretical foundation, modeling issues, and numerical implementation of the Lagrangian–Eulerian (LE) approach for multiphase flows. The LE approach is based on a statistical description of the dispersed phase in terms of a stochastic point pro- cess that is coupled with an Eulerian statistical representation of the carrier fluid phase. A modeled transport equation for the particle distribution function—also known as Williams’ spray equation in the case of sprays—is indirectly solved using a Lagrangian particle method. Interphase transfer of mass, momentum and energy are represented by coupling terms that appear in the Eulerian conservation equa- tions for the fluid phase. This theoretical foundation is then used to develop LE submodels for interphase interactions such as momentum transfer. Every LE model implies a corresponding closure in the Eulerian-Eulerian two–fluid theory, and these moment equations are derived. Approaches to incorporate multiscale interactions between particles (or spray droplets) and turbulent eddies in the carrier gas that result in better predictions of particle (or droplet) dispersion are described. Nu- merical convergence of LE implementations is shown to be crucial to the success of the LE modeling approach. It is shown how numerical convergence and accuracy of an LE implementation can be established using grid–free estimators and computa- tional particle number density control algorithms. This review of recent advances establishes that LE methods can be used to solve multiphase flow problems of prac- tical interest, provided submodels are implemented using numerically convergent algorithms. -

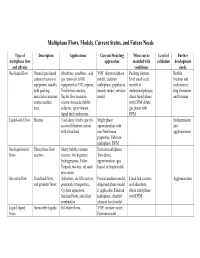

Type of Multiphase Flow and Physics

Multiphase Flows, Models, Current Status, and Future Needs Type of Description Applications Current Modeling What can be Level of Further multiphase flow approaches modeled with validation development and physics confidence needs Gas-liquid flow General gas-liquid Absorbers, scrubbers, acid VOF, dispersed phase Packing element Bubble contact reactors or gas removal (AGR) model, Eulerian level small scale breakup and equipment, usually equipment in CO2 capture, multiphase, population models to coalescence, with packing Trickle bed reactors, density model, mixture understand physics; slug formation material to increase Taylor flow in micro model dilute liquid phase and breakup contact surface reactor channels, bubble with DPM; dilute area. columns, spray towers, gas phase with liquid fuel combustors DPM Liquid-solid flow Slurries Coal slurry feeder, gravity Single phase Sedimentation assisted filtration system approximation with and with fixed bed, non-Newtonian agglomeration properties, Eulerian multiphase, DPM Gas-liquid-solid Three phase flow Slurry bubble column Eulerian multiphase, flows reactors reactors, bio digesters, Two-phase hydrogenators, Fisher approximation (gas Tropsch reactors, oil sand liquid, or liquid solid) processors Gas-solid flow Fixed bed flows Adsorbers, air-lift reactors, Porous medium model, Fixed bed reactors Agglomeration, and granular flows pneumatic transporters, dispersed phase model and adsorbers, Cyclone separators, if applicable, Eulerian dilute solid phase fluidized beds, solid fuel multiphase, detailed with DPM combustors element level model Liquid-liquid Immiscible liquids Oil-water flows, VOF, mixture model, flows Eulerian model General challenges for all multiphase flows: 1. Solution speed up with code optimization and algorithm improvement to bring turn-around time to practical level for the inherently time dependent problems in multiphase flows.