Modesty Blaise As an Action Heroine in the Canon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modesty Blaise: Gallows Bird Free

FREE MODESTY BLAISE: GALLOWS BIRD PDF Peter O'Donnell,Enric Badia Romero | 128 pages | 01 Jul 2006 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781840238686 | English | London, United Kingdom Comics: Modesty Blaise When you buy a book, we donate a book. Modesty Blaise: Gallows Bird in. Apr 01, ISBN Modesty Blaise: Gallows Bird to Cart. Also available from:. Paperback —. Also in Modesty Blaise. Product Details. Inspired by Your Browsing History. Joshua Williamson. Monkey vs. Robot: The Complete Epic. James Kochalka. Nightwing Vol. Sundays with Walt and Skeezix. John Constantine, Hellblazer Vol. Paul Jenkins. Corto Maltese: In Siberia. Scott Snyder. Jeff Lemire and Ray Fawkes. Arkham Asylum: Madness. Grifter Vol. Nathan Edmondson. Green Lantern: New Guardians Vol. Justin Jordan. Northlanders Vol. Kingdom Of The Wicked. Ian Edginton. Superman: Grounded Vol. Michael Straczynski. Superman: Secret Origin Deluxe Edition. Eerie Archives Volume 1. Len Strazewski. Batwoman Vol. Haden Blackman and J. Williams III. Batgirl: A Celebration of 50 Years. Green Lantern: Sector Vol. Martin Pasko. Absolute Batman Year One. Frank Miller. Batman: Knightfall Vol. Gary Panter. Batman Beyond Vol. Adventures of Superman by George Perez. George Perez. Batman Vol. Related Articles. Looking for More Great Reads? Download Hi Res. Modesty Blaise: The Gallows Bird. LitFlash The eBooks you want at the lowest prices. Read it Forward Read it first. Pass Modesty Blaise: Gallows Bird on! Stay in Touch Sign up. We are experiencing technical difficulties. Please try again later. Become a Member Start earning points for buying books! Slings & Arrows This article will be permanently flagged as inappropriate and made unaccessible to everyone. Are you certain this article is inappropriate? Email Address:. -

Annual Report Contains Names And/ Or Images of People Who Have Passed Away

ABORIGINAL LEGAL SERVICE OF WA LTD ANNUAL ACN: 617 555 843 REPORT 2020 BLACK LIVES MATTER In Australia, we have faced the tragedy of 28.6%, despite Aboriginal people making up only unnecessary loss of life of our First Nations Peoples approximately 3% of the total Australian population. for too long. The study also stated that Aboriginal people are A key finding of the 1991 Royal Commission into 10 times more likely to die in prison than non- Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) found that Indigenous people and in June 2020, confirmed Aboriginal people are more likely to die in custody that there have been at least 434 deaths since the because they are arrested and imprisoned at RCIADIC ended in 1991. disproportionate rates. For a Royal Commission that The Perth Black Lives Matter protest in June 2020 commenced in 1987, the fact that many of the 339 saw Aboriginal people and supporters come out in recommendations have still not been implemented their thousands, as a show of support against racism is unacceptable. and the dehumanising treatment that so many Aboriginal people have endured. This was part of a The Guardian conducted a study of Aboriginal larger global movement saying ‘enough is enough – deaths in custody and, after reading 589 coronial we stand against racism’. reports, found ‘a record of systemic failure and neglect’. Their investigation revealed that in 1991, See page 26 for a statement by NATSILS, the 14.3% of the male prison population in Australia was National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Aboriginal but by March 2020 this had increased to Services in July 2020. -

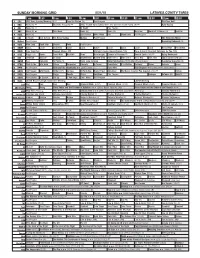

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Dragon Magazine

May 1980 The Dragon feature a module, a special inclusion, or some other out-of-the- ordinary ingredient. It’s still a bargain when you stop to think that a regular commercial module, purchased separately, would cost even more than that—and for your three bucks, you’re getting a whole lot of magazine besides. It should be pointed out that subscribers can still get a year’s worth of TD for only $2 per issue. Hint, hint . And now, on to the good news. This month’s kaleidoscopic cover comes to us from the talented Darlene Pekul, and serves as your p, up and away in May! That’s the catch-phrase for first look at Jasmine, Darlene’s fantasy adventure strip, which issue #37 of The Dragon. In addition to going up in makes its debut in this issue. The story she’s unfolding promises to quality and content with still more new features this be a good one; stay tuned. month, TD has gone up in another way: the price. As observant subscribers, or those of you who bought Holding down the middle of the magazine is The Pit of The this issue in a store, will have already noticed, we’re now asking $3 Oracle, an AD&D game module created by Stephen Sullivan. It for TD. From now on, the magazine will cost that much whenever we was the second-place winner in the first International Dungeon Design Competition, and after looking it over and playing through it, we think you’ll understand why it placed so high. -

Birmingham Science Fiction Group Newsletter

(Honorary Presidents: Brian W. Aldiss Birmingham and Harry Harrison) Science Fiction Group NEWSLETTER 130 JUNE 1982 The Birmingham Science Fiction Group has its formal meeting on the third Friday of each month in the upstairs room of THE IVY BUSH pub on the cor ner of Hagley Road and Monument Road, Edgbaston, Birmingham 16. There is also an informal meeting on the first Tuesday of each month at THE OLD ROYAL pub, on the corner of Church Street and Cornwall Street, Birmingham 3. (Church Street is off Colmore Row.) New members are always welcome. Our treasurer is Margaret Thorpe, 36 Twyford Road, Ward End, Birmingham 8. The 12-months subscription is £3.50. JUNE MEETING - Friday 18th June at 7.45 pm DAVE LANGFORD is coming to tell us a fairy story. He is one of the wittiest and most amusing writers in SF today. Few British writers have ever been nominated for the US-dominated Hugo awards, but he has been a short-listed nominee four times, for fan writing, and his fanzine Twll Ddu has been short-listed once. He is also a former TAFF winner and Eastercon fan guest-of-honour, but has now turned professional, and is one of the young est full-time writers of SF in Britain. His first SF novel, The Space Eater, is being published as an Arrow paperback this month, and it is not beyond the realms of possibility that he will have a few words to say about it. (Such as "Buy a copy!*) Another of his books, Facts and Fallacies (co-written with Chris Morgan, of whom some of you might perhaps have heard), is re-emerging later this month in the guise of a Corgi paperback. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI' The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties By Nancy McGuire Roche A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University May 2011 UMI Number: 3464539 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3464539 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Spectacle of Gender: Representations of Women in British and American Cinema of the Nineteen-Sixties Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: Dr. William Brantley, Committees Chair IVZUs^ Dr. Angela Hague, Read Dr. Linda Badley, Reader C>0 pM„«i ffS ^ <!LHaAyy Dr. David Lavery, Reader <*"*%HH*. a*v. Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department ;jtorihQfcy Dr. Michael D1. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies Nancy McGuire Roche Approved: vW ^, &v\ DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the women of my family: my mother Mary and my aunt Mae Belle, twins who were not only "Rosie the Riveters," but also school teachers for four decades. These strong-willed Kentucky women have nurtured me through all my educational endeavors, and especially for this degree they offered love, money, and fierce support. -

{DOWNLOAD} Modesty Blaise

MODESTY BLAISE - THE YOUNG MISTRESS Author: Peter ODonnell Number of Pages: 104 pages Published Date: 24 Jun 2014 Publisher: Titan Books Ltd Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781781167090 DOWNLOAD: MODESTY BLAISE - THE YOUNG MISTRESS Modesty Blaise - The Young Mistress PDF Book THE POCKET PARENT is, literally, a pocket-size book of tried-and-true advice, common sense, parental wisdom, and sanity. plus homemade (and healthy!) pizza, chicken fingers, brownies, margaritas, and more. America's Cheapest Family Gets You Right on the Money: Your Guide to Living Better, Spending Less, and Cashing in on Your DreamsDo you have too much month at the end of your money. Against this dismal backdrop, David Dupper presents a transformative new model of school discipline that is preventive, proactive, and relationship-based. ) This book is an outgrowth of a conference on learning trajectories, hosted in 2009 at North Carolina State University, which examined research on learning trajectories. Through eleven radical new insights, Brooks takes us to the extreme frontiers of what we understand about the world. Learn how to make calls and play songs by voice control, take great photos, keep track of your schedule, and much more with complete step-by-step instructions and crystal-clear explanations by iPhone master David Pogue. Recently, there has been a growing interest in optimization algorithms based on principles observed in nature, termed Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs). Dividing this history into distinct eras (1880 to World War I, interwar, post-World War II to 1970), Frank Uekoetter compares and contrasts the influence of political, class, and social structures, scientific communities, engineers, industrial lobbies, and environmental groups in each nation. -

Read Book # Articles on Peter O'donnell, Including: Cobra Trap

RBBEXFAPKUSN # Kindle // Articles On Peter O'donnell, including: Cobra Trap, Pieces Of Modesty, I, Lucifer,... A rticles On Peter O'donnell, including: Cobra Trap, Pieces Of Modesty, I, Lucifer, Th e Silver Mistress, Modesty Blaise (novel), Sabre-tooth , A Taste For Death (modesty Blaise), Th e Impossible V irgin, Filesize: 3.25 MB Reviews Extensive guide! Its this kind of excellent read through. it absolutely was writtern very perfectly and helpful. Your way of life period is going to be change when you complete reading this ebook. (Murphy Dooley) DISCLAIMER | DMCA X5E2CL5LN5X4 \ Book // Articles On Peter O'donnell, including: Cobra Trap, Pieces Of Modesty, I, Lucifer,... ARTICLES ON PETER O'DONNELL, INCLUDING: COBRA TRAP, PIECES OF MODESTY, I, LUCIFER, THE SILVER MISTRESS, MODESTY BLAISE (NOVEL), SABRE-TOOTH, A TASTE FOR DEATH (MODESTY BLAISE), THE IMPOSSIBLE VIRGIN, To get Articles On Peter O'donnell, including: Cobra Trap, Pieces Of Modesty, I, Lucifer, The Silver Mistress, Modesty Blaise (novel), Sabre-tooth, A Taste For Death (modesty Blaise), The Impossible Virgin, PDF, remember to refer to the link below and save the file or gain access to other information which might be in conjuction with ARTICLES ON PETER O'DONNELL, INCLUDING: COBRA TRAP, PIECES OF MODESTY, I, LUCIFER, THE SILVER MISTRESS, MODESTY BLAISE (NOVEL), SABRE-TOOTH, A TASTE FOR DEATH (MODESTY BLAISE), THE IMPOSSIBLE VIRGIN, ebook. Hephaestus Books, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. PRINT ON DEMAND Book; New; Publication Year 2016; Not Signed; Fast Shipping from -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55407

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #110 June 2015 - August 2015 Hours: M-F 10am to 8pm Sat. 10am to 6pm Sun. Noon to 5pm Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Fax 612-827-6394 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.UncleHugo.com Parking Metered parking (25 cents for 20 minutes) is available in front of the store. Meters are enforced 8am-6pm Monday through Saturday (except for federal holidays). Note the number on the pole you park by, and pay at the box located between the dental office driveway and Popeyes driveway. The box accepts quarters, dollar coins, and credit cards, and prints a receipt that shows the expiration time. Meter parking for vehicles with Disability License Plates or a Disability Certificate is free. (Rates and hours shown are subject to change without notice - the meters are run by the city, not by us.) Free parking is also available in the dental office lot from 5pm-8pm Monday through Thursday, and all day Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Autographing Events (at Uncle Hugo's) Sunday, July 19, 3-4pm: Wesley Chu - Time Salvager Saturday, August 8, 1-2pm: Kelly McCullough - School for Sidekicks Sharon Lee and Steve Miller have a new Liaden Universe collection, A Liaden Universe Constellation Volume 3 ($14.00), expected the beginning of August. We’ve arranged to have Sharon and Steve to sign a hundred copies and ship them to us. If you order from our website by July 1, you can also get your copy personalized if you like. -

MONDO TARANTINO MONDO TARANTINO COLEÇÃO CINUSP – Volume 4 Coordenação Geral Tradução Esther Hamburger E Patricia Moran David Donato

MONDO TARANTINO MONDO TARANTINO COLEÇÃO CINUSP – vOLUME 4 COORDENAÇÃO GERAL TRADUÇÃO Esther Hamburger e Patricia Moran David Donato ORGANIZAÇÃO REVISÃO Marcos Kurtinaitis Luciana Tonelli PRODUÇÃO PROJETO GRÁFICO E DIAGRAMAÇÃO Thiago de André André Noboru Siraiama Uva Costriuba PESQUISA Henrique Figueiredo ILUSTRAÇÃO DA CAPA Yasmin Afshar Vitor Morinishi Kurtinaitis, Marcos (org.) Mondo Tarantino / Marcos Kurtinaitis São Paulo: Pró-reitoria de Cultura e Extensão Universitária – USP, 2013. 256 p.; 21 x 15,5 cm. ISBN 978-85-62587-09-2 1. Cineastas 2. Tarantino, Quentin (1963- ) I. Título CDD 791.43092 CDU 791 Ministério da Cultura apresenta Banco do Brasil apresenta e patrocina MONDO TARANTINO CCBB DF CCBB SP CINUSP 15 FEV A 17 MAR 20 FEV A 17 MAR 25 FEV A 15 MAR SCES, Trecho 2 Rua Álvares Penteado, 112 Rua do Anfiteatro, 181 61 3108 - 7600 Centro Colmeia Favo 04 twitter.com/ccbb_df 11 3113 - 3651 / 3652 11 3091 - 3540 fb.com/ccbb.brasilia twitter.com/ccbb_sp www.usp.br/cinusp fb.com/ccbbsp fb.com/cinusp.pauloemilio CORREALIZAÇÃO REALIZAÇÃO Pró-Reitoria de Cultura e Extensão Universitária da USP São Paulo – Fevereiro de 2013 O Ministério da Cultura e o Banco do Brasil apresentam, em parceria com o CINUSP Paulo Emílio, a mostra MONDO TARANTINO, ampla retrospectiva em homenagem ao cineasta que completa 20 anos de carreira. Prestes a completar também 50 anos de idade e contando com enorme prestígio, Quentin Tarantino é, sem dúvida, um dos mais influentes cineastas em atividade. Seus filmes, tamanha a originalidade, sempre provocam as mais acaloradas discussões. E, mais que isso, propiciam uma significativa mudança no cinema. -

Modesty Blaise Kindle

MODESTY BLAISE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter O'Donnell | 224 pages | 28 Oct 2005 | Souvenir Press Ltd | 9780285637283 | English | London, United Kingdom Modesty Blaise PDF Book For example, a romance is established between Willie and Modesty, even though the comic strip firmly established only a platonic relationship between them. It was possibly done with the intent of making Modesty the focus of attention, but it just looks more like sloppiness than anything else. In this story, she has been retired and is living in London, when the secret service asks her to come out retirement to help them stop a major robbery I've read two other books in this series but finally managed to snag a copy of the first book. Runtime: min. No, not because of the current issues but for lack of interest in the U. Jan 31, Tony Bird rated it it was amazing. Vincent Vega's bathroom book from Pulp Fiction. The fourth Modesty Blaise title sees the rugged te… More. In , Penguin Books of India reprinted the full series. Modesty narrowly survives several attempts on her life by Gabriel's assassins, whose failure leads to their swift execution by the ruthless Mrs. Meanwhile, at his island hideaway, Gabriel Sir Dirk Bogarde , the diamond thief, has his own plans for Blaise and Garvin. Having conceived the idea after a chance meeting with a girl during his wartime service in the Middle East, [4] O'Donnell elected to work with Jim Holdaway, with whom he had worked on the strip Romeo Brown , after a trial period of collaboration with Frank Hampson , creator of Dan Dare , left O'Donnell dissatisfied. -

From Alien Shores #4 August 2013 Letters of Comment May Be Sent to [email protected] from Alien Shores Is a Back Numbers Press Production

In This Issue: Danger 5 Lost Girl Yellow zone Nine Tail Fox Django Servant of the Jackal God The Sword Big Sky Modesty Blaise Van Canto Delain Solomon Kane Nacho Vigalondo Pericles David Koresh Superstar And... ØBattlelore Page 62 ØDelain Page 49 ∏The Great Magician David Koresh Ø Page 34 æLost Girl Superstar Page 54 ∏Yellow Zone Page 73 Page 19 ±Modesty Blaise ØVan Canto Page 91 Page 63 æNine Tail Fox ÆPericles Page 68 Page 96 ∑Nacho Vigalondo Page 50 ØThe Sword ∏Django ∏Solomon Kane Page 27 Page 75 Page 103 ©Bauhinia Heroine Page 32 About This Issue ß Page 3 Big Sky Page 8 Letters of Comment Note: ®Servant of the Jackal God Page 6 Click on the title Page 87 of an article to be taken to it. Click on the globe coliphon at the end of any article to return to æDanger 5 the contents page Page 10 From Alien Shores #4 August 2013 Letters of Comment may be sent to [email protected] From Alien Shores is a Back Numbers Press production. From Alien Shores is published whenever editor Jack Avery gets around to it. All contents copyright individual creators unless otherwise noted. Welcome to the fourth issue of insensitive discussing an event that left edies about fighting Nazis. There’s a From Alien Shores. This was supposed a lot of people dead. It was probably limit to how much of the 3rd Reich I to be a “leftovers” issue to clear out a fair cop, and so it was something I want in my zine, even if they are be- the inventory before the upcoming wanted to work on before publishing ing mocked.