A Practical Exercise in Appellate Ethics David H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules of Professional Conduct for Attorneys at Law

RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT FOR ATTORNEYS AT LAW TABLE OF CONTENTS Rule TRANSACTIONS WITH PERSONS Preamble: A Lawyer’s Responsibilities OTHER Scope THAN CLIENTS 1.0. Terminology Rule CLIENT-LAWYER RELATIONSHIP 4.1. Truthfulness in statements to others. 4.2. Communication with person represented 1.1. Competence. by counsel. 1.2. Scope of representation and allocation of 4.3. Dealing with unrepresented persons. authority between client and lawyer. 4.4. Respect for rights of third persons. 1.3. Diligence. LAW FIRMS AND ASSOCIATIONS 1.4. Communication. 1.5. Fees. 5.1. Responsibilities of partners, managers, 1.6. Confidentiality of information. and supervisory lawyers. 1.7. Conflict of interest: current clients. 5.2. Responsibilities of a subordinate lawyer. 1.8. Conflict of interest: current clients: specific 5.3. Responsibilities regarding nonlawyer prohibited transactions. assistance. 1.9. Duties to former clients. 5.4. Professional independence of a lawyer. 1.10. Imputation of conflicts of interest: gen- 5.5. Unauthorized practice of law; eral rule. multijurisdictional practice of law. 1.11. Special conflicts of interest for former and 5.6. Restrictions on right to practice. current government officers and 5.7. Responsibilities regarding law-related ser- employees. vices. 1.12. Former judge, arbitrator, mediator, or PUBLIC SERVICE other third-party neutral. 1.13. Organization as client. 6.1. Pro bono public service. 1.14. Client with diminished capacity. 6.2. Accepting appointments. 1.15. Safekeeping property. 6.3. Membership in legal services 1.15A. [Repealed]. organization. 1.16. Declining or terminating representation. 6.4. Law reform activities affecting client 1.17. Sale of law practice. -

Staying Ethical in an In-House Legal Environment

Staying Ethical in an In-House Legal Environment Presented by: Mark Freel Jeremy Weinberg Laura N. Wilkinson Partner Senior Attorney Partner Locke Lord LLP Hasbro, Inc. Locke Lord LLP [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Providence, RI Providence, RI Providence, RI In conjunction with: April 3, 2019 Ethics for In-House Counsel Under the Rules of Professional Conduct June 8, 2017 Pag AM 68266307.1 Locke Lord LLP and Association of Corporation Counsel—Northeast Present Staying Ethical in an In-House Legal Environment Table of Contents Tab Number Description of Document Tab 1 Power Point: “Staying Ethical in an In-House Legal Environment” Tab 2 Form of language for representing both the company and the employee Tab 3 The Association of the Bar of the City of New York Committee on Professional and Judicial Ethics Formal Opinion 2004-02: Representing Corporations and Their Constituents in the Context of Governmental Investigations Tab 4 Representing the Company in an Internal Investigation: Upjohn Warning and District of Columbia Opinion 269 (1/15/97) Tab 5 Sarbanes-Oxley Part 205: Standards of Professional Conduct for Attorneys Appearing and Practicing Before the Commission in the Representation of an Issuer Tab 6 Social Media Ethics Guidelines of the Commercial and Federal Litigation Section of the New York State Bar Association Tab 7 ABA Formal Opinion 99-415: Representation Adverse to Organization by Former In-House Lawyer Tab 8 The Association of the Bar of the City of New York Committee on Professional and Judicial Ethics Formal Opinion 2008-02: Corporate Legal Departments and Conflicts of Interest Between Represented Corporate Affiliates Tab 9 Rhode Island Supreme Court Ethics Advisory Panel Opinion No. -

The Judge's Ethical Duty to Report Misconduct by Other Judges And

Hofstra Law Review Volume 25 | Issue 3 Article 4 1997 The udJ ge's Ethical Duty to Report Misconduct by Other Judges and Lawyers and its Effect on Judicial Independence Leslie W. Abramson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, Leslie W. (1997) "The udJ ge's Ethical Duty to Report Misconduct by Other Judges and Lawyers and its Effect on Judicial Independence," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 25: Iss. 3, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol25/iss3/4 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abramson: The Judge's Ethical Duty to Report Misconduct by Other Judges and THE JUDGE'S ETHICAL DUTY TO REPORT MISCONDUCT BY OTHER JUDGES AND LAWYERS AND ITS EFFECT ON JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE Leslie W Abramson* CONTENTS I. INTRODUCnON ............................... 752 If. A JUDGE'S ETHICAL DUTY TO REPORT LAWYERS AND OTHER JUDGES ...................... 755 A. Comparing the 1972 and 1990 Code Provisions ..... 760 B. Comparing a Judge's Duty to Report with a Lawyer's Duty to Report ................ 763 III. A JUDGE'S DUTY TO REPORT ....................... 766 A. When Does the Duty to Report Arise? ............ 766 B. What Misconduct Should or Must Be Reported? ..... 769 C. What Is an AppropriateAction or DisciplinaryMeasure for the Judge to Pursue? ..... 771 IV. EXCEPTIONS TO THE DUTY TO REPORT ............... -

A Study of State Judicial Discipline Sanctions

A STUDY OF STATE JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE SANCTIONS BY CYNTHIA GRAY This study was developed under grant #SJI-01-N-203 from the State Justice Institute. Points of view expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official positions or policies of the American Judica- ture Society or the State Justice Institute. American Judicature Society Allan D. Sobel Executive Vice President and Director Cynthia Gray Director Center for Judicial Ethics Copyright 2002, American Judicature Society Library of Congress Control Number: 2002113760 ISBN: 1-928919-13-8 Order #138 American Judicature Society 180 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 600 Chicago, Illinois 60601-7401 (312) 558-6900 Fax (312) 558-9175 www.ajs.org 10/02 Founded in 1913, the American Judicature Society is an independent, nonprofit organization sup- ported by a national membership of judges, lawyers, and other members of the public. Through research, educational programs, and publications, AJS addresses concerns related to ethics in the courts, judicial selection, the jury, court administration, judicial independence, and public understanding of the justice system. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 OVERVIEW OF JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE 3 THE PURPOSE OF JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE 3 THE STANDARD FOR REMOVAL 4 REMOVING AN ELECTED JUDGE 4 STANDARD OF REVIEW FOR JUDICIAL DISCIPLINE SANCTIONS 5 AVAILABLE SANCTIONS 6 REMOVAL FROM JUDICIAL OFFICE 7 INTRODUCTION 7 TYPES OF MISCONDUCT FOR WHICH JUDGES HAVE BEEN REMOVED 8 Misconduct related to a judge’s duties or power 8 Combination of misconduct related to judicial duties and -

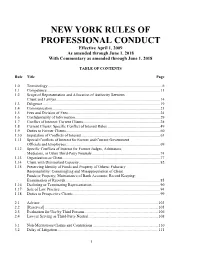

RULES of PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As Amended Through June 1, 2018 with Commentary As Amended Through June 1, 2018

NEW YORK RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Effective April 1, 2009 As amended through June 1, 2018 With Commentary as amended through June 1, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rule Title Page 1.0 Terminology ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Competence .................................................................................................................... 11 1.2 Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and Lawyer .......................................................................................................... 14 1.3 Diligence ........................................................................................................................ 19 1.4 Communication .............................................................................................................. 21 1.5 Fees and Division of Fees .............................................................................................. 24 1.6 Confidentiality of Information ....................................................................................... 29 1.7 Conflict of Interest: Current Clients............................................................................... 38 1.8 Current Clients: Specific Conflict of Interest Rules ...................................................... 49 1.9 Duties to Former Clients ................................................................................................ 60 1.10 Imputation of Conflicts -

The Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct

The Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct As adopted by the Colorado Supreme Court on April 12, 2007, effective January 1, 2008, and amended through April 6, 2016 SYNOPSIS Rule 1.0. Terminology CLIENT-LAWYER RELATIONSHIP Rule 1.1. Competence Rule 1.2. Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and Lawyer Rule 1.3. Diligence Rule 1.4. Communication Rule 1.5. Fees Rule 1.6. Confidentiality of Information Rule 1.7. Conflict of Interest: Current Clients Rule 1.8. Conflict of Interest: Current Clients: Specific Rules Rule 1.9. Duties to Former Clients Rule 1.10. Imputation of Conflicts of Interest: General Rule Rule 1.11. Special Conflicts of Interest for Former and Current Government Officers and Employees Rule 1.12. Former Judge, Arbitrator, Mediator or Other Third-party Neutral Rule 1.13. Organization as Client Rule 1.14. Client with Diminished Capacity Rule 1.15. Safekeeping Property (Repealed) Rule 1.15A. General Duties of Lawyers Regarding Property of Clients and Third Parties Rule 1.15B. Account Requirements Rule 1.15C. Use of Trust Accounts Rule 1.15D. Required Records Rule 1.15E. Approved Institutions Rule 1.16. Declining or Terminating Representation Rule 1.16A. Client File Retention Rule 1.17. Sale of Law Practice Rule 1.18. Duties to Prospective Client COUNSELOR Rule 2.1. Advisor Rule 2.2. Intermediary 1 Rule 2.3. Evaluation for Use by Third Persons Rule 2.4. Lawyer Serving as Third-party Neutral ADVOCATE Rule 3.1. Meritorious Claims and Contentions Rule 3.2. Expediting Litigation Rule 3.3. Candor Toward the Tribunal Rule 3.4. -

Ohio Rules of Professional Conduct

OHIO RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT (Effective February 1, 2007; as amended effective June 17, 2020) TABLE OF CONTENTS Preamble: A Lawyer’s Responsibilities; Scope 1 1.0 Terminology 5 Client-Lawyer Relationship 1.1 Competence 11 1.2 Scope of Representation and Allocation of Authority Between Client and 14 Lawyer 1.3 Diligence 18 1.4 Communication 20 1.5 Fees and Expenses 24 1.6 Confidentiality of Information 31 1.7 Conflict of Interest: Current Clients 39 1.8 Conflict of Interest: Current Clients: Specific Rules 50 1.9 Duties to Former Clients 61 1.10 Imputation of Conflicts of Interest: General Rule 65 1.11 Special Conflicts of Interest for Former and Current Government Officers 70 and Employees 1.12 Former Judge, Arbitrator, Mediator, or Other Third-Party Neutral 74 1.13 Organization as Client 77 1.14 Client with Diminished Capacity 82 1.15 Safekeeping Funds and Property 86 1.16 Declining or Terminating Representation 92 1.17 Sale of Law Practice 96 1.18 Duties to Prospective Client 102 Counselor 2.1 Advisor 105 2.2 [Reserved for future use; no corresponding ABA Model Rule] 2.3 Evaluation for Use by Third Persons 107 2.4 Lawyer Serving as Arbitrator, Mediator, or Third-Party Neutral 110 Advocate 3.1 Meritorious Claims and Contentions 112 3.2 Expediting Litigation [Not Adopted; See Note] 113 3.3 Candor toward the Tribunal 114 3.4 Fairness to Opposing Party and Counsel 119 3.5 Impartiality and Decorum of the Tribunal 121 3.6 Trial Publicity 124 3.7 Lawyer as Witness 127 3.8 Special Responsibilities of a Prosecutor 130 3.9 Advocate in Nonadjudicative -

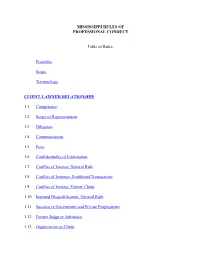

Professional Conduct, Miss. Rules Of

MISSISSIPPI RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT Table of Rules Preamble. Scope. Terminology. CLIENT-LAWYER RELATIONSHIP 1.1 Competence. 1.2 Scope of Representation. 1.3 Diligence. 1.4 Communication. 1.5 Fees. 1.6 Confidentiality of Information. 1.7 Conflict of Interest: General Rule. 1.8 Conflict of Interests: Prohibited Transactions. 1.9 Conflict of Interest: Former Client. 1.10 Imputed Disqualification: General Rule. 1.11 Successive Government and Private Employment. 1.12 Former Judge or Arbitrator. 1.13 Organization as Client. 1.14 Client Under a Disability. 1.15 Safekeeping Property. Mississippi IOLTA Program Notice of Election. 1.16 Declining or Terminating Representation. 1.17 Sale of Law Practice. COUNSELOR 2.1 Advisor. 2.2 Intermediary. 2.3 Evaluation for Use by Third Persons. ADVOCATE 3.1 Meritorious Claims and Contentions. 3.2 Expediting Litigation. 3.3 Candor Toward the Tribunal. 3.4 Fairness to Opposing Party and Counsel. 3.5 Impartiality and Decorum of the Tribunal. 3.6 Trial Publicity. 3.7 Lawyer as Witness. 3.8 Special Responsibilities of a Prosecutor. 3.9 Advocate in Nonadjudicative Proceedings. TRANSACTIONS WITH PERSON OTHER THAN CLIENTS 4.1 Truthfulness in Statements to Others. 2 4.2 Communication With Person Represented by Counsel. 4.3 Dealing with Unrepresented Person. 4.4 Respect for Rights of Third Persons. LAW FIRMS AND ASSOCIATIONS 5.1 Responsibilities of a Partner or Supervisory Lawyer. 5.2 Responsibilities of a Subordinate Lawyer. 5.3 Responsibilities Regarding Non-Lawyer Assistants. 5.4 Professional Independence of a Lawyer. 5.5 Unauthorized Practice of Law. 5.6 Restrictions on Right to Practice. -

Judicial Ethics Benchguide

JUDICIAL ETHICS BENCHGUIDE: ANSWERS TO FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS June 2020 A Project of the Florida Court Education Council’s Publications Committee ABOUT THE AUTHOR Blan L. Teagle is currently the Executive Director of the Judicial Qualifications Commission. He served from 2003–2020 as a Deputy State Courts Administrator of the Florida Office of the State Courts Administrator. At the time of writing the first edition of this benchguide, he was the Director of the Center for Professionalism at The Florida Bar. From 1989 to 1998, Mr. Teagle served as staff counsel to the Judicial Ethics Advisory Committee as part of his duties as a senior attorney at the Office of the State Courts Administrator. He holds a B.A. from the University of the South (Sewanee), a J.D. from the University of Florida College of Law, where he was editor-in-chief of the University of Florida Law Review, and an M.P.S. (a graduate degree in pastoral theology) from Loyola University, New Orleans. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Susan Leseman, John Meeks, and Deborah Lacombe for their collaboration on previous judicial ethics materials upon which this benchguide is based. He would also like to thank Todd Engelhardt for his research assistance with the first edition of this benchguide. DISCLAIMER Viewpoints presented in this publication do not reflect any official policy or position of the Florida Supreme Court, the Office of the State Courts Administrator, the Florida judicial conferences, the Florida Court Education Council, or the Florida Court Education Council’s Publications Committee. Nor do they represent any official position of the Florida Judicial Qualifications Commission; the 2020 edition was edited prior to Blan Teagle assuming his role with the JQC. -

Commission on Judicial Conduct 29Th Annual Report 2019-2019

COMMISSION ON JUDICIAL CONDUCT 29th ANNUAL REPORT 2018-2019 ORGANIZATION, JURISDICTION AND POWERS The Commission on Judicial Conduct was established on June 1, 1979, by the Supreme Court of Hawaiʻi under Rule 26 of its Rules of Court. In 1984, Rule 26 was renumbered to Rule 8. The establishment of the Commission was mandated by Article VI, Section 5 of the Hawaiʻi State Constitution, as amended in 1978. The Rules of Court set forth the Commission’s basic operational procedures and powers. The Commission consists of seven members appointed for staggered three-year terms. The Rules require that three members shall be attorneys licensed to practice in the State of Hawaiʻi, and that four members shall be citizens who are not active or retired judges or lawyers. The Commission has jurisdiction over all judges and per diem judges of the State of Hawaiʻi. Excluding arbitrators, the Commission also has jurisdiction over court appointed officers performing judicial functions. In April 1993, the Supreme Court amended Rule 8.2(a) which now empowers the Commission to issue advisory opinions to aid judges in the interpretation of the Code of Judicial Conduct. These opinions are admissible in disciplinary action against the judge involved. COMPLAINTS AGAINST JUDGES Any person may file a complaint relating to the conduct of a judge. Upon receipt of the complaint, the Commission shall determine whether sufficient cause exists to proceed with an investigation. Judicial misconduct involves any violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct. Disability involves the physical or mental inability to perform judicial duties and functions. Judicial misconduct does not include making erroneous findings of fact, reaching an erroneous legal conclusion, or erroneously applying the law. -

How to Complain About Lawyers and Judges in New York City

How to Complain About Lawyers and Judges in New York City COMMITTEE ON PROFESSIONAL DISCIPLINE JUNE 2012 NEW YORK CITY BAR ASSOCIATION 42 WEST 44TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10036 INTRODUCTION The New York City Bar Association, which was founded in 1870, has more than 23,000 members. One of the City Bar’s functions is to act as a resource for information about legal and judicial ethics. This pamphlet explains how the disciplinary system for lawyers and judges operates. You should review this if you are considering whether to complain about a lawyer, judge or court employee. Complaints Against Lawyers Lawyers have ethical responsibilities to their clients, the courts and others that are identified in the New York Rules of Professional Conduct. A copy of the Rules may be found at http://courts.state.ny.us/rules/jointappellate/NY%20Rules%20of%20Prof%20Conduct_09.pdf. If a lawyer meaningfully violates a Rule of Professional Conduct, he or she is subject to discipline administered by a governmental agency affiliated with the court system. The following are examples of conduct by lawyers that may result in discipline. 1. Neglect. Lawyers are generally prohibited from neglecting their clients’ cases. Neglect does not occur merely because a lawyer fails to return a telephone call as quickly as the client wishes, or because a case is not proceeding through the court system as fast as the client might want. Rather, neglect occurs when a lawyer repeatedly and consistently fails to communicate with his or her client, or where a failure by the lawyer to take action means that the client has lost a valuable right, such as right to bring a claim, assert a defense, appeal a decision or make a motion. -

Chapter 4. Rules of Professional Conduct Preamble: a Lawyer’S Responsibilities

CHAPTER 4. RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT PREAMBLE: A LAWYER’S RESPONSIBILITIES A lawyer, as a member of the legal profession, is a representative of clients, an officer of the legal system, and a public citizen having special responsibility for the quality of justice. As a representative of clients, a lawyer performs various functions. As an adviser, a lawyer provides a client with an informed understanding of the client’s legal rights and obligations and explains their practical implications. As an advocate, a lawyer zealously asserts the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system. As a negotiator, a lawyer seeks a result advantageous to the client but consistent with requirements of honest dealing with others. As an evaluator, a lawyer acts by examining a client’s legal affairs and reporting about them to the client or to others. In addition to these representational functions, a lawyer may serve as a third-party neutral, a nonrepresentational role helping the parties to resolve a dispute or other matter. Some of these rules apply directly to lawyers who are or have served as third-party neutrals. See, e.g., rules 4- 1.12 and 4-2.4. In addition, there are rules that apply to lawyers who are not active in the practice of law or to practicing lawyers even when they are acting in a nonprofessional capacity. For example, a lawyer who commits fraud in the conduct of a business is subject to discipline for engaging in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation. See rule 4-8.4. In all professional functions a lawyer should be competent, prompt, and diligent.