Capuchin Monkeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development Team

Paper No. : 14 Human Origin and Evolution Module : 09 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Dr. Satwanti Kapoor (Retd Professor) Paper Coordinator Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Mr. Vijit Deepani & Prof. A.K. Kapoor Content Writer Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Prof. R.K. Pathak Content Reviewer Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh 1 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Anthropology Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name Human Origin and Evolution Module Name/Title Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Module Id 09 Contents: Primates: A brief Outline Classification of Living Primates Distribution of Living Primates Summary Learning Objectives: To understand the classification of living primates. To discern the distribution of living primates. 2 Classification and Distribution of Living Primates Anthropology Primates: A brief Outline Primates reside at the initial stage in the series of evolution of man and therefore constitute the first footstep of man’s origin. Primates are primarily mammals possessing several basic mammalian features such as presence of mammary glands, dense body hair; heterodonty, increased brain size, endothermy, a relatively long gestation period followed by live birth, considerable capacity for learning and behavioural flexibility. St. George J Mivart (1873) defined Primates (as an order) -

Black Capped Capuchin (Cebus Apella)

Husbandry Manual For Brown Capuchin/Black-capped Capuchin Cebus apella (Cebidae) Author: Joel Honeysett Date of Preparation: March 2006 Sydney Institute of TAFE, Ultimo Course Name and Number: Captive Animals. Lecturer: Graeme Phipps TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Taxonomy ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Nomenclature ................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Subspecies ...................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Recent Synonyms ........................................................................................................... 5 2.4 Other Common Names ................................................................................................... 5 3 Natural History ....................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Morphometrics ............................................................................................................... 7 3.1.1 Mass And Basic Body Measurements ....................................................................... 7 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism .................................................................................................. -

Factors Affecting Cashew Processing by Wild Bearded Capuchin Monkeys (Sapajus Libidinosus, Kerr 1792)

American Journal of Primatology 78:799–815 (2016) RESEARCH ARTICLE Factors Affecting Cashew Processing by Wild Bearded Capuchin Monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus, Kerr 1792) ELISABETTA VISALBERGHI1*, ALESSANDRO ALBANI1,2, MARIALBA VENTRICELLI1, PATRICIA IZAR3, 1 4 GABRIELE SCHINO , AND DOROTHY FRAGAZSY 1Istituto di Scienze e Tecnologie della Cognizione, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Rome, Italy 2Dipartimento di Scienze, Universita degli Studi Roma Tre, Rome, Italy 3Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Sao~ Paolo, Sao~ Paolo, Brazil 4Department of Psychology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Cashew nuts are very nutritious but so well defended by caustic chemicals that very few species eat them. We investigated how wild bearded capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus) living at Fazenda Boa Vista (FBV; Piauı, Brazil) process cashew nuts (Anacardium spp.) to avoid the caustic chemicals contained in the seed mesocarp. We recorded the behavior of 23 individuals toward fresh (N ¼ 1282) and dry (N ¼ 477) cashew nuts. Adult capuchins used different sets of behaviors to process nuts: rubbing for fresh nuts and tool use for dry nuts. Moreover, adults succeed to open dry nuts both by using teeth and tools. Age and body mass significantly affected success. Signs of discomfort (e.g., chemical burns, drooling) were rare. Young capuchins do not frequently closely observe adults processing cashew nuts, nor eat bits of nut processed by others. Thus, observing the behavior of skillful group members does not seem important for learning how to process cashew nuts, although being together with group members eating cashews is likely to facilitate interest toward nuts and their inclusion into the diet. These findings differ from those obtained when capuchins crack palm nuts, where observations of others cracking nuts and encounters with the artifacts of cracking produced by others are common and support young individuals’ persistent practice at cracking. -

Consequences of Color Vision Variation on Performance and Fitness in Capuchin Monkeys

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 Consequences of color vision variation on performance and fitness in capuchin monkeys Andrea Theresa Green Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Green, Andrea Theresa, "Consequences of color vision variation on performance and fitness in capuchin monkeys" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10766. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSEQUENCES OF COLOR VISION VARIATION ON PERFORMANCE AND FITNESS IN CAPUCHIN MONKEYS By ANDREA THERESA GREEN Masters of Arts, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 2007 Bachelors of Science, Warren Wilson College, Asheville, NC, 1997 Dissertation Paper presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Organismal Biology and Ecology The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2014 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Charles H. Janson, Chair Division of Biological Sciences Erick Greene Division of Biological Sciences Doug J. Emlen Division of Biological Sciences Scott R. Miller Division of Biological Sciences Gerald H. Jacobs Psychological & Brain Sciences-UCSB UMI Number: 3628945 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Enrichment for Nonhuman Primates, 2005

A six-booklet series on providing appropriate enrichment for baboons, capuchins, chimpanzees, macaques, marmosets and tamarins, and squirrel monkeys. Contents ...... Introduction Page 4 Baboons Page 6 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues References Common Names of the Baboon Capuchins Page 17 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of Capuchins Chimpanzees Page 28 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of Chimpanzees contents continued on next page ... Contents Contents continued… ...... Macaques Page 43 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues Resources Common Names of the Macaques Sample Pair Housing SOP -- Macaques Marmosets and Tamarins Page 58 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Safety Issues References Common Names of the Callitrichids Squirrel Monkeys Page 73 Background Social World Physical World Special Cases Problem Behaviors Safety Issues References Common Names of Squirrel Monkeys ..................................................................................................................... For more information, contact OLAW at NIH, tel (301) 496-7163, e-mail [email protected]. NIH Publication Numbers: 05-5745 Baboons 05-5746 Capuchins 05-5748 Chimpanzees 05-5744 Macaques 05-5747 Marmosets and Tamarins 05-5749 Squirrel Monkeys Contents Introduction ...... Nonhuman primates maintained in captivity have a valuable role in education and research. They are also occasionally used in entertainment. The scope of these activities can range from large, accredited zoos to small “roadside” exhib- its; from national primate research centers to small academic institutions with only a few monkeys; and from movie sets to street performers. Attached to these uses of primates comes an ethical responsibility to provide the animals with an environment that promotes their physical and behavioral health and well-be- ing. -

Population Density of Cebus Imitator, Honduras

Neotropical Primates 26(1), September 2020 47 POPULATION DENSITY ESTIMATE FOR THE WHITE-FACED CAPUCHIN MONKEY (CEBUS IMITATOR) IN THE MULTIPLE USE AREA MONTAÑA LA BOTIJA, CHOLUTECA, HONDURAS, AND A RANGE EXTENSION FOR THE SPECIES Eduardo José Pinel Ramos M.Sc. Biological Sciences, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras, Cra. 27 a # 67-14, barrio 7 de agosto, Bogotá D.C., e-mail: <[email protected]> Abstract Honduras is one of the Neotropical countries with the least amount of information available regarding the conservation status of its wild primate species. Understanding the real conservation status of these species is relevant, since they are of great importance for ecosystem dynamics due to the diverse ecological services they provide. However, there are many threats that endanger the conservation of these species in the country such as deforestation, illegal hunting, and illegal wild- life trafficking. The present research is the first official registration of the Central American white-faced capuchin monkey (Cebus imitator) for the Pacific slope in southern Honduras, increasing the range of its known distribution in the country. A preliminary population density estimate of the capuchin monkey was performed in the Multiple Use Area Montaña La Botija using the line transect method, resulting in a population density of 1.04 groups/km² and 4.96 ind/km² in the studied area. These results provide us with a first look at an isolated primate population that has never been described before and demonstrate the need to develop long-term studies to better understand the population dynamics, ecology, and behaviour, for this group in the zone. -

Exam 1 Set 3 Taxonomy and Primates

Goodall Films • Four classic films from the 1960s of Goodalls early work with Gombe (Tanzania —East Africa) chimpanzees • Introduction to Chimpanzee Behavior • Infant Development • Feeding and Food Sharing • Tool Using Primates! Specifically the EXTANT primates, i.e., the species that are still alive today: these include some prosimians, some monkeys, & some apes (-next: fossil hominins, who are extinct) Diversity ...200$300&species& Taxonomy What are primates? Overview: What are primates? • Taxonomy of living • Prosimians (Strepsirhines) – Lorises things – Lemurs • Distinguishing – Tarsiers (?) • Anthropoids (Haplorhines) primate – Platyrrhines characteristics • Cebids • Atelines • Primate taxonomy: • Callitrichids distinguishing characteristics – Catarrhines within the Order Primate… • Cercopithecoids – Cercopithecines – Colobines • Hominoids – Hylobatids – Pongids – Hominins Taxonomy: Hierarchical and Linnean (between Kingdoms and Species, but really not a totally accurate representation) • Subspecies • Species • Genus • Family • Infraorder • Order • Class • Phylum • Kingdom Tree of life -based on traits we think we observe -Beware anthropocentrism, the concept that humans may regard themselves as the central and most significant entities in the universe, or that they assess reality through an exclusively human perspective. Taxonomy: Kingdoms (6 here) Kingdom Animalia • Ingestive heterotrophs • Lack cell wall • Motile at at least some part of their lives • Embryos have a blastula stage (a hollow ball of cells) • Usually an internal -

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

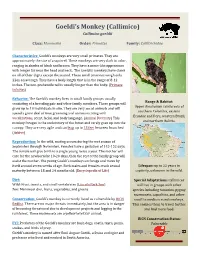

Goeldi's Monkey

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

Genome Sequence of the Basal Haplorrhine Primate Tarsius Syrichta Reveals Unusual Insertions

ARTICLE Received 29 Oct 2015 | Accepted 17 Aug 2016 | Published 6 Oct 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms12997 OPEN Genome sequence of the basal haplorrhine primate Tarsius syrichta reveals unusual insertions Ju¨rgen Schmitz1,2, Angela Noll1,2,3, Carsten A. Raabe1,4, Gennady Churakov1,5, Reinhard Voss6, Martin Kiefmann1, Timofey Rozhdestvensky1,7,Ju¨rgen Brosius1,4, Robert Baertsch8, Hiram Clawson8, Christian Roos3, Aleksey Zimin9, Patrick Minx10, Michael J. Montague10, Richard K. Wilson10 & Wesley C. Warren10 Tarsiers are phylogenetically located between the most basal strepsirrhines and the most derived anthropoid primates. While they share morphological features with both groups, they also possess uncommon primate characteristics, rendering their evolutionary history somewhat obscure. To investigate the molecular basis of such attributes, we present here a new genome assembly of the Philippine tarsier (Tarsius syrichta), and provide extended analyses of the genome and detailed history of transposable element insertion events. We describe the silencing of Alu monomers on the lineage leading to anthropoids, and recognize an unexpected abundance of long terminal repeat-derived and LINE1-mobilized transposed elements (Tarsius interspersed elements; TINEs). For the first time in mammals, we identify a complete mitochondrial genome insertion within the nuclear genome, then reveal tarsier-specific, positive gene selection and posit population size changes over time. The genomic resources and analyses presented here will aid efforts to more fully understand the ancient characteristics of primate genomes. 1 Institute of Experimental Pathology, University of Mu¨nster, 48149 Mu¨nster, Germany. 2 Mu¨nster Graduate School of Evolution, University of Mu¨nster, 48149 Mu¨nster, Germany. 3 Primate Genetics Laboratory, German Primate Center, Leibniz Institute for Primate Research, 37077 Go¨ttingen, Germany. -

Capuchins Are the Most Intelligent New World Monkeys – Perhaps As Intelligent As Chimpanzees

Hooded Capuchin Cebus paella cay Capuchin IQ - Capuchins are the most intelligent New World monkeys – perhaps as intelligent as chimpanzees. They are noted for their ability to fashion and use tools. Because of their ability to learn and remember, they were once trained as “organ grinder” monkeys, are often used in movies and have even been trained to assist disabled people with routine tasks around the house. Get a Grip - Hooded capuchins have a semi-prehensile tail that they can use to grip objects. They have opposable thumbs and big toes on their hands and feet further enabling them to easily manipulate objects. They use their prehensile tail to anchor themselves when climbing around in the trees and to keep them from falling when they sleep. Unlike some monkeys with prehensile tails, capuchins cannot hang by their tail alone. Classification The hooded capuchin is also been referred to as the tufted or brown capuchin. Class: Mammalia Order: Primate Family: Cebidae Genus: Cebus Species: paella Subspecies: cay Distribution This species ranges through northern South America, specifically Venezuela, Brazil, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Habitat Canopies of tropical and mountain rainforests. Physical Description • Hooded capuchins are 12-22 inches (30-56 cm) long with a 15-22 inch (38-56 cm) tail. • Adults weigh six to eight pounds (3-4 kg). • Their fur is light to dark brown with a distinctive black cap on the head. • They have semi-prehensile tails. • Hooded capuchins have tufts of hair that form ridges along the side of the top of their head. Diet What Does It Eat? In the wild: Fruit, flowers, leaves, insects, birds, eggs, lizards, and small mammals. -

F a C T S H E

F A C T S H E E T Recent Primate Incidents Demonstrate Risks To Public Health and Safety, Animal Welfare November 2009 (Indiana): A woman was holding her 10-month-old granddaughter near an enclosure where a monkey was kept as a pet. The monkey pulled the hood of the girl’s coat, causing her head to strike the metal cage, and pulled her hair. The child was taken to the hospital and released that night. November 2009 (Tennessee): A capuchin monkey was found on a road. He had escaped from an SUV of a family vacationing in the area while they were eating at a restaurant, and was recaptured. November 2009 (Florida): A macaque monkey was on the loose outside a Pinellas County apartment complex. October 2009 (Kentucky): Authorities found a baboon being kept in the garage of a Kenton County home. The owners said they bought the animal from an Ohio dealer, and they surrendered her to a sanctuary. September 2009 (Florida): Authorities were looking for a pet patas monkey who had escaped from a Marion County home and been on the loose about two months. June 2009 (New Hampshire): An employee of a farm was severely bitten by a macaque monkey after leaving an enclosure unsecured. Macaques often carry Herpes B virus, and research published by the CDC concludes the health risk makes macaques unsuitable as pets. April 2009 (Oregon): A man brought a capuchin monkey in a diaper to a park. A 6-year-old girl approached and the animal jumped on her, causing two puncture wounds below her eye.