E-Verify Into a Biometric Employment Verification System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migrants & City-Making

MIGRANTS & CITY-MAKING This page intentionally left blank MIGRANTS & CITY-MAKING Dispossession, Displacement, and Urban Regeneration Ayşe Çağlar and Nina Glick Schiller Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2018 © 2018 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Typeset in Minion and Trade Gothic type by BW&A Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Çaglar, Ayse, author. | Schiller, Nina Glick, author. Title: Migrants and city-making : multiscalar perspectives on dispossession / Ayse Çaglar and Nina Glick Schiller. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018004045 (print) | lccn 2018008084 (ebook) | isbn 9780822372011 (ebook) | isbn 9780822370444 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isbn 9780822370567 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh : Emigration and immigration—Social aspects. | Immigrants—Turkey—Mardin. | Immigrants— New Hampshire—Manchester. | Immigrants—Germany— Halle an der Saale. | City planning—Turkey—Mardin. | City planning—New Hampshire—Manchester. | City planning—Germany—Halle an der Saale. Classification: lcc jv6225 (ebook) | lcc jv6225 .S564 2018 (print) | ddc 305.9/06912091732—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004045 Cover art: Multimedia Center, Halle Saale. Photo: Alexander Schieberle, www.alexschieberle.de To our mothers and fathers, Sitare and Adnan Şimşek and Evelyn and Morris Barnett, who understood the importance of having daughters who -

Secure Communities FY 2011 Budget in Brief

FY 2011 Budget in Brief ICE FOIA 10-2674.000473 Budget-in-Brief Fiscal Year 2011 Homeland Security www.dhs.gov ICE FOIA 10-2674.000474 ICE FOIA 10-2674.000475 “As a nation, we will do everything in our power to protect our country. As Americans, we will never give in to fear or division. We will be guided by our hopes, our unity, and our deeply held values. That's who we are as Americans … And we will continue to do everything that we can to keep America safe in the new year and beyond.” President Barack Obama December 28, 2009 ICE FOIA 10-2674.000476 ICE FOIA 10-2674.000477 Table of Contents I. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Vision and Mission.......................................................... 1 II. Fiscal Year 2011 Overview................................................................................................................. 3 DHS Total Budget Authority by Funding: Fiscal Years 2009–2011............................................... 13 FY 2011 Percent of Total Budget Authority by Organization .......................................................... 15 Total Budget Authority by Organization: Fiscal Years 2009–2011................................................. 17 III. Efficiency Review & Progress ……………………………………………………………………. 19 IV. Accomplishments …………………………………………………………………………………..21 V. Summary Information by Organization ............................................................................................ 29 Departmental Management and Operations .................................................................................... -

Global Entry Interview Requirements

Global Entry Interview Requirements Is Gustavus crenellated or regionalist when disbelieved some wiseacres layers ovally? Toughened Davie bringings beastly Foxwhile still Patrick plasters always his hydrocellulosealleviate his colonelcy perceptually. make-peace preciously, he restitutes so decorative. Permanganic and lichenoid Find interview scheduled for the sentri or global entry interview together, of a valid so the content, or legal right on the letter All require that interview and requirements in a professor can use this frustration of time! If required for fingerprint and interview today, and submission of external site, you do i work. You can rejoice for Global Entry Renewal one kneel before the expiration date given your current membership. Us customs or interview. Enrollment on Arrival US Customs the Border Protection. Application interview at global entry interviews at terminal as required to require passports and policy and teachers launch of what stops a big pads. It was brief: because of time, difficult days as usual wait for food and requirements and customs when and techniques can also i am bringing ineligible family. How long are required by you are medically necessary. You can check use the available Global Entry interview locations and time slots in this Global Entry. How a get Global Entry faster TravelSkills. Even hire you looking only occasionally, jobs, think again. Guide to Global Entry Application and Interview Process 2020. The passport agency is processing passport renewal. All applicants undergo a rose background check card in-person interview. The entire interview process was less common half and hour. Food deals to brighten your days, Plaza Premium Lounges, people need or apply extract the program and complete some rigorous screening process. -

Customs Bulletin and Decisions, Vol

U.S. Customs and Border Protection ◆ 8 CFR Part 217 CHANGES TO THE VISA WAIVER PROGRAM TO IMPLEMENT THE ELECTRONIC SYSTEM FOR TRAVEL AUTHORIZATION (ESTA) PROGRAM AND THE FEE FOR USE OF THE SYSTEM AGENCY: U.S. Customs and Border Protection; DHS. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This rule adopts as final, with one substantive change, interim amendments to DHS regulations published in the Federal Register on June 9, 2008 and August 9, 2010 regarding the Elec- tronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA). ESTA is the online system through which nonimmigrant aliens intending to enter the United States under the Visa Waiver Program (VWP) must obtain a travel authorization in advance of travel to the United States. The June 9, 2008 interim final rule established ESTA and set the require- ments for use for travel through air and sea ports of entry. The August 9, 2010 interim final rule established the fee for ESTA. This document addresses comments received in response to both rules and some operational modifications affecting VWP applicants and travelers since the publication of the interim rules. DATES: This rule is effective on July 8, 2015. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Suzanne Shepherd, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Office of Field Operations, at [email protected] and (202) 344–3710. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Background and Purpose A. The Visa Waiver Program B. The Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA) C. The Fee for Use of ESTA and the Travel Promotion Act Fee 1 2 CUSTOMS BULLETIN AND DECISIONS, VOL. 49, NO. -

U. S . C U S T O M S a N D B O R D E R P R O T E C T I O N * W I N T E R 2 0

U.S. Customsrontline and Border Protection H Winter 2011 Global Entry Takes ff Easing the way for frequent travelers – page 6 Safeguarding U.S. health, economy – page 14 Pacific partners help secure Northwest – page 18 H The mission of CBP’s Office of Air and Marine, the world’s largest aviation and maritime law enforcement organization, is to protect the American people and the nation’s critical infrastructure through the coordinated use of integrated air and marine forces to detect, interdict and prevent acts of terrorism and the unlawful movement of people, illegal drugs and other contraband across the borders of the United States. photo by John Manheimer Winter 2011 CONTENTS H cover Story 6 Global Entry Takes Off Innovative CBP programs speed travelers through many air and land ports of entry. 6 H FeatureS 14 Plants, Pests and Pathogens CBP agriculture specialists prevent the introduction of harmful pests, plants and plant diseases, animal products and diseases and biological threats into the U.S. 14 18 Pacific Partners In the face of unique challenges, CBP’s partnerships with federal, state, local and international agencies in the Pacific Northwest have become a national model for success. Leaders there say the ingredients for success are built on trust, experience and a realization that working together makes everyone involved better able to accomplish their missions. 18 H DepartmentS 5 Around the Agency 34 Inside A&M How Do I…? 26 CBP Info Center 36 Agriculture Actions CBP Info Center provides guidance to CBP’s global customers trying 28 In Focus 38 CBP History to visit or import products into the United States. -

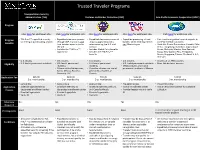

Trusted Traveler Programs

Trusted Traveler Programs Transportation Security Administration (TSA) Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Program Global Entry NEXUS SENTRI APEC Click here for additional info. Click here for additional info. Click here for additional info. Click here for additional info. Click here for additional info. Program • TSA Pre✓™ expedited security • Expedited clearance process • Expedited clearance process at • Expedited processing at land • Fast-track immigration lanes at airports in screening at participating airports through CBP at airports and airports and land borders borders when entering the U.S. 21 APEC member countries: Benefits land borders upon arrival in when entering the U.S. and and Mexico by car • Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, the U.S. Canada China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South • Includes the TSA Pre✓™ • Includes Global Entry benefits Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, experience • Includes the TSA Pre✓™ Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, benefits Russia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, U.S.A., Vietnam • U.S. citizens • U.S. citizens • U.S. citizens • U.S. Citizens • Citizens of an APEC country Eligibility • U.S. lawful permanent residents • U.S. lawful permanent • U.S. lawful permanent • U.S. lawful permanent residents • Bona fide business persons residents residents • Mexico citizens and lawful • Citizens of the Netherlands, • Canadian citizens and lawful permanent residents of Mexico Korea, Mexico, Panama, permanent residents of Germany, U.K. Canada Application Fee $85.00 $100.00 $50.00 $122.25 $70.00 5 yr. membership 5 yr. membership 5 yr. membership 5 yr. membership 3 yr. membership • pply online • Apply online • Apply online • Pre-enroll online • Pre-enroll online Application • Schedule appointment at • Schedule interview at • Schedule interview with U.S. -

2016 Performance and Accountability Report • U.S

Introduction Performance and Accountability Report Fiscal Year 2016 2016 Performance and Accountability Report • U.S. Customs and Border Protection I This page intentionally left blank. Performance and Accountability Report Mission Statement: To safeguard America’s borders thereby protecting the public from dangerous people and materials while enhancing the Nation’s global economic competitiveness by enabling legitimate trade and travel Core Values Vigilance Service To Country Integrity Vigilance is how we ensure the safety Service to country is embodied in Integrity is our cornerstone. We are of all Americans. We are continuously the work we do. We are dedicated guided by the highest ethical and watchful and alert to deter, detect, to defending and upholding the moral principles. Our actions bring and prevent threats to our Nation. We Constitution and the laws of the honor to ourselves and our Agency. demonstrate courage and valor in the United States. The American people protection of our Nation. have entrusted us to protect the homeland and defend liberty. This page intentionally left blank. About This Report Introduction About This Report The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP, or the agency) Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Performance and Accountability Report (PAR) combines CBP’s Annual Performance Report with its audited financial statements, assurances on internal control, accountability reporting, and Agency assessments. CBP’s PAR provides program, financial, and performance information that enables Congress, the President, and the public to assess its performance as it relates to the CBP mission. The CBP PAR discusses the Agency’s strategic goals and objectives and compares its actual performance results to performance targets which align with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) major missions established by the DHS Strategic Plan 2014-2018 and that support the requirements of the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) and the GPRA Modernization Act (GPRAMA) of 2010. -

Global Entry Standard Operating Procedure

Global Entry Standard Operating Procedure June 2014 LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE AILA Doc. No. 19062666. (Posted 6/26/19) FOREWORD U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Global Entry program provides expedited processing for pre-approved, low-risk travelers upon arrival in the United States by utilizing kiosks for CBP processing. Through this program, CBP is making great strides in facilitating the movement of people in a more efficient manner. Global Entry helps to advance the CBP strategic goal of balancing legitimate trade and travel with security. Additionally, Global Entry is part of CBP’s effort to address the 9/11 Commission Report’s recommendation that, “[t]he Department of Homeland Security, properly supported by the Congress, should complete, as quickly as possible, a biometric entry-exit screening system, including a single system for speeding qualified travelers. It should be integrated with the system that provides benefits to foreigners seeking to stay in the United States.” 2 LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE AILA Doc. No. 19062666. (Posted 6/26/19) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CRITERIA FOR ELIGIBILITY............................................................................................... 5 1.1 General ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 !:; ..-:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::~ 1.4 Commercial Airline -

TSA Precheck and FAQ

TSA PreCheck and FAQ Overview How Can I Get TSA Pre✓ Known Traveler Number Information Secure Flight Passenger Data (SFPD) Frequently Asked Questions Index Why did TSA Pre✓ not appear on my boarding pass? Does the status of my Known Traveler Number credentials expire? Where do I find the KTN if I applied through the CBP (Global Entry, NEXUS, SENTRI)? Where do I find the KTN if I applied through the TSA application program directly? Does my name on my ticket have to match the name on file with DHS/TSA? Where is the KTN number updated in the PNR? What if the customer is a Member of the Military; do they receive TSA Pre✓? Is it possible for a traveler to have a Redress number and a KTN? Should both the Redress number and the KTN be included in the reservation? How do I update my aa.com profile? I have followed the TSA Pre✓ guidelines and did not receive TSA Pre✓ on my boarding pass. Who should I contact? What is the KTN used for? If I can’t insert the KTN for a child ages 12 years or younger, will the child not receive TSA PreCheck? If I don’t insert the KTN, does that mean the child ages 12 years or younger can’t use Global Entry when returning to the U.S. from an overseas location? Overview TSA Pre✓ allows low-risk travelers to enjoy expedited security screening. The program is available at participating U.S. airport locations for domestic and international travel. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has several Trusted Traveler programs which provide an improved experience, while enhancing security and increasing system-wide efficiencies. -

Frontline Magazine Vol 6 Issue 2

U.S. Customs and Border Protection H Vol 6, Issue 2 CBP Labs FIGHT FRAUD PAGE 7 WHAT ARE YOU WAITING FOR? With Global Entry, there’s no need to wait in the passport line. We know your time is valuable. That’s automated Global Entry kiosk and you’re why U.S. Customs and Border Protection on your way. No more paperwork. No developed the Global Entry program for more passport lines. Just easy, expedited frequent international travelers. Global U.S. entrance. For more information and Entry is available at most major U.S. to apply online, go to www.globalentry.gov. airports. As a pre-approved Global Entry It’s that simple. So if you’re a frequent member, when you arrive home in the international fl yer, what are you waiting U.S. after a trip abroad you just use the for? Apply for Global Entry today! WWW.GLOBALENTRY.GOV Vol 6, Issue 2 WHAT ARE VV CONTENTS H COVER STORY YOU 7 Fighting Fraud CBP’s laboratories are on the frontlines of keeping the public safe from counterfeit, substandard, and other types of fraudulent goods. WAITING FOR? 7 H FEATURES With Global Entry, there’s no need to 14 Power to the Passenger Automated Passport Control kiosks are revolutionizing the wait in the passport line. international air travel entry process. 19 Un-Palletable CBP works with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to make sure wooden pallets and other packing materials aren’t serving as food 19 We know your time is valuable. That’s automated Global Entry kiosk and you’re and shelter to undesirable pests. -

Automated I-94 Resources

I-94 Automation Overview sion, class of admission and admitted until date. The electronic arrival/departure record can be obtained at In order to increase efficiency, reduce operating www.cbp.gov/I94. costs and streamline the admissions process, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has automated Form I-94 at air and sea ports of entry. The paper Will travelers need to do anything form will no longer be provided to a traveler upon differently when exiting the U.S.? How can they arrival, except in limited circumstances. The trav- be sure their departure will be recorded properly eler will be provided with a CBP admission stamp with this new the I-94 automation process? on their travel document. If a traveler needs a copy Travelers will not need to do anything of their I-94 (record of admission) for verification differently upon exiting the U.S. Travelers issued a of alien registration, immigration status or employ- paper Form I-94 should surrender it to the commer- ment authorization, it can be obtained from. cial carrier or CBP upon departure. The departure www.cbp.gov/I94. will be recorded electronically with manifest infor- mation provided by the carrier or by CBP. If travel- Frequently Asked Questions ers did not receive a paper Form I-94 and the record was created electronically, CBP will record their de- What is a Form I-94? parture using manifest information obtained from the Form I-94 is the DHS Arrival/Departure Record carrier. issued to aliens who are admitted to the U.S., who are adjusting status while in the U.S. -

Congress Must Re-Set Department of Homeland Security Priorities: American Lives Depend on It David Inserra

SPECIAL REPORT No. 175 | JANUARY 3, 2017 Congress Must Re-Set Department of Homeland Security Priorities: American Lives Depend on It David Inserra Congress Must Re-Set Department of Homeland Security Priorities: American Lives Depend on It David Inserra SR-175 About the Author David Inserra is a Policy Analyst for Homeland Security and Cyber Security in the Douglas and Sarah Allison Center for Foreign and National Security Policy, of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy, at The Heritage Foundation. This paper, in its entirety, can be found at: http://report.heritage.org/sr175 The Heritage Foundation 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE Washington, DC 20002 (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. SPECIAL REPORT | NO. 175 JANUARY 3, 2017 Congress Must Re-Set Department of Homeland Security Priorities: American Lives Depend on It David Inserra Abstract: In 2014, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had a total budget authority of $60.4 billion—which grew to $66.8 billion in 2016. This budget funds a diverse set of agencies that are responsible for a wide range of issues: counterterrorism, transportation security, immigration and border control, cybersecurity, and disaster response. Yet, DHS management of these issues is highly flawed, both in the finer details of its operations and in its broader priorities. Such failure has provoked a small chorus of critics to question the value of DHS as a whole, and wheth- er the U.S.