Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Statement of LIVECHAT Software SA

Financial statement of LIVECHAT Software SA for the business year from April 1st, 2019 until March 31st, 2020 drawn up in accordance with the Accounting Act Wrocław, June 30th, 2020 CONTENTS STATEMENT OF THE BOARD INTRODUCTION TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENT AND COMPARABLE FINANCIAL DATA ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENT BALANCE SHEET (in PLN) PROFIT AND LOSS STATEMENT (in PLN) LIST OF CHANGES IN THE EQUITY CASH FLOW STATEMENT (in PLN) FURTHER INFORMATION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES Notes to the balance sheet Note 1.1. Intangible assets Note 1.2 Changes in intangible assets Note 1.3 Intangible assets ( ownership structure) Note 2.1 Tangible assets Note 2.2 Changes in fixed assets Note 2.3 Fixed assets ( ownership structure) Note 2.4 Fixed assets shown off-balance sheet Note 3.1 Long-term receivables Note 4 Real property Note 4.2 Intangible assets Note 4.3 Long-term financial assets Note 4.3 Long-term financial assets Note 4.4 Shares and stocks in subsidiaries Note 4.5 Securities, shares and other long-term financial assets Note 4.6 Securities, shares and other long-term financial assets Note 4.7 Granted long-term loans Note 4.8 Other long-term investments Note 5.1 Change in the assets balance due to deferred income tax Note 5.2 Other prepayments Note 7.1 Short-term receivables Note 7.2 Short-term receivables from related parties Note 7.3 Changes in the balance of write-offs to short-term receivables Note 7.4 Gross short-term receivables Note 7.5 Gross trade receivables from other parties with remaining maturities from the balance sheet date Note 7.6 Overdue trade receivables (gross) Note 7.7 Overdue long-term and short-term receivables (gross) Note 8.1 Short-term financial assets Note 8.2 Cash and cash equivalents ( currency structure) Note 8.3 Securities, shares and other short-term financial assets Note 8.4. -

Improvements in Accounting and Analysis of Financial Results In

ACCESS Freely available online urism & OPEN o H f T o o s l p a i t n a r l i u t y o J Journal of ISSN: 2167-0269 Tourism & Hospitality Research Article Improvements in Accounting and Analysis of Financial Results in Tourism Enterprises Temirkhanova Mo'tabar Juraevna* Department of International Economy, Russian University of Economics, Named after G.V. Plekhanova in Tashkent, Uzbekistan ABSTRACT The article deals with improvements in accounting and analysis of financial results in tourism enterprises, as well as suggestions for further simplification of the order of calculation of financial results of tourism companies as a result of explorative and deductive research, as a result of researches. With major changes in the development of the industry, the system of indicators that reflect the financial results of the tourism enterprises, benefits and operating results should be studied on a regular basis. These reviews are derived from the financial statement report. This will require the formulation of this report form and the improvement of its information. This does not disclose information about the earnings and net earnings from this report to external users. Keywords: International standards; Costs; Accountability; Improvement; Financial results; Travel companies INTRODUCTION and share in the economy, the diversification and quality of tourist services, and the expansion of tourism infrastructure" [4]. Since the early days of independence, the tourism industry has been paying much attention. As a result, the non-traceable sector is now In the above mentioned documents the goals and priorities of the one of the leading sectors of the economy. -

Notice of Filing of Proposed Rules on Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value Measurements, and Amendments to PCAOB Auditing Standards

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION (Release No. 34-85434; File No. PCAOB-2019-02) March 28, 2019 Public Company Accounting Oversight Board; Notice of Filing of Proposed Rules on Auditing Accounting Estimates, Including Fair Value Measurements, and Amendments to PCAOB Auditing Standards Pursuant to Section 107(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (the "Act" or "Sarbanes-Oxley Act"), notice is hereby given that on March 20, 2019, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (the "Board" or "PCAOB") filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (the "Commission" or "SEC") the proposed rules described in Items I and II below, which items have been prepared by the Board. The Commission is publishing this notice to solicit comments on the proposed rules from interested persons. I. Board's Statement of the Terms of Substance of the Proposed Rules On December 20, 2018, the Board adopted a new rule and amendments to auditing standards (collectively, the "proposed rules"), under which the three existing standards related to auditing estimates, including fair value measurements, will be replaced with a single, updated standard. The text of the proposed rules appears in Exhibit A to the SEC Filing Form 19b-4 and is available on the Board’s website at https://pcaobus.org/Rulemaking/Pages/docket-043-auditing-accounting-estimates-fair- value-measurements.aspx and at the Commission’s Public Reference Room. II. Board's Statement of the Purpose of, and Statutory Basis for, the Proposed Rules In its filing with the Commission, the Board included statements concerning the purpose of, and basis for, the proposed rules and discussed any comments it received on 1 the proposed rules. -

Quarterly Financial Report Third Quarter 2020

Quarterly Financial Report Third Quarter 2020 Quarterly Financial Report / Third Quarter 2020 Contents Page Key Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 The Company ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Share Performance ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Interim Management Report ............................................................................................................................... 6 Consolidated Interim Financial Statements ...................................................................................... 16 Consolidated Statements of Income ...................................................................................................... 16 2 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income .......................................................... 17 Consolidated Balance Sheets ...................................................................................................................... 18 Consolidated Statements of Shareholders’ Equity .................................................................. 19 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows ....................................................................................... -

Consolidated Financial Results for the First Quarter of the Fiscal Year

Consolidated Financial Results For the First Quarter of the Fiscal Year Ending March 31, 2022 (For the First Three Months Ended June 30, 2021) Prepared in Conformity with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in Japan English Translation from the Original Japanese-Language Document July 30, 2021 Company Name : Mazda Motor Corporation (Tokyo Stock Exchange / Code No. 7261) URL : https://www.mazda.com/ Representative Person : Akira Marumoto, Representative Director and President Contact Person : Nobuhiko Kageyama, General Manager, Accounting Department, Financial Services Division Phone 082-282-1111 Filing of Shihanki Hokokusho, quarterly securities report : Scheduled for August 6, 2021 Payment of Dividends : - Supplementary Material : Yes Briefing Session : Yes (Intended for securities analysts, institutional investors and media) (in Japanese yen rounded to millions, except amounts per share) 1. Consolidated Financial Highlights (April 1, 2021 through June 30, 2021) (1) Consolidated Financial Results (Percentage indicates change from same period of the previous fiscal year) Net Income Attributable Net Sales Operating Income Ordinary Income to Owners of the Parent millions of yen % millions of yen % millions of yen % millions of yen % FY2022 1st quarter 803,399 113.3 26,106 ‐ 26,518 ‐ 11,377 ‐ FY2021 1st quarter 376,676 (55.6) (45,272) ‐ (41,751) ‐ (66,691) ‐ Note: Comprehensive income FY2022 1st quarter 21,069 millions of yen ( ‐ % ) FY2021 1st quarter (65,008) millions of yen ( ‐ % ) Net Income Net Income Per Share Per Share (Diluted) yen yen FY2022 1st quarter 18.06 18.05 FY2021 1st quarter (105.89) ‐ (2) Consolidated Financial Position Total Assets Net Assets Equity Ratio As of millions of yen millions of yen % June 30, 2021 2,997,739 1,207,987 39.8 March 31, 2021 2,917,414 1,195,830 40.5 Reference: Net Assets excluding non-controlling interests As of June 30, 2021 1,193,489 millions of yen As of March 31, 2021 1,181,730 millions of yen 2. -

The Impact of the Accounting Policies on the Share Prices of Companies and Banks

THE IMPACT OF THE ACCOUNTING POLICIES ON THE SHARE PRICES OF COMPANIES AND BANKS Malgorzata Bialas, PhD AGH, University of Science and Technology, Faculty of Management, Department of Economics, Finance and Environmental Protection, Poland Abstract: This article concerns the impact of accounting policies on the share price of companies and banks in Poland. The article draws attention to the profit and loss account, which contains an increasing number of records that are not a reflection of actual operations, but for example the valuation of balance sheet items in fair value. Therefore, the result which is calculated on an accrual basis is different from the result calculated on cash basis. The study shows the degree of differences between the results in the profit and loss account and the results in the cash flow statement. It is noted that the degree of differences for banks is lower than in the case of companies. Then the correlation coefficient between changes in stock prices and the gap between the income statement and cash flow statement is calculated. It is shown that the correlation coefficient is very weak. Key Words: Fair value, profit and loss account, cash flow statement, market value of company Introduction The accounting policies have a very big impact on the financial statements. Investors during the decision process are guided by the information which is contained in the financial statements. Recently accounting principles have changed. As a result, fair value was introduced for valuation of the items of balance sheet. The effects of this valuation are reported also in the income statement. -

Financial Result Q1 2019 Use of Gas in Transport Continued to Grow

GASUM GROUP FINANCIAL RESULT Q1 2019 USE OF GAS IN TRANSPORT CONTINUED TO GROW KEY FINANCIAL INDICATORS JANUARY 1 TO MARCH 31, 2019 • Group revenue increased by 2% and totaled €396.6 million (2018: €390.5 million). • Operating profit totaled €61.1 million, down 16% year on year (€72.8 million). • Balance sheet total increased to €1,628.2 million (€1,526.6 million) following the introduc- tion of the new IFRS 16 standard. • The Group’s financial position remained strong in the reporting period, with the equity ratio being 42.5% (December 31, 2018: 43.7%). KEY FIGURES € million 1–3/2019 1–3/2018 Change 2018 Revenue 396.6 390.5 1.5% 1,177.4 Operating profit 61.1 72.8 -16.1% 124.2 Operating profit (%) 15.4% 18.6% 10.5% Equity ratio (%) 42.5% 41.2% 43.7% Return on equity (%) * 11.7% 14.6% 13.3% Return on investment (%) * 8.3% 10.1% 9.2% Balance sheet total 1,628.2 1,565.5 4.0% 1,526.6 Net interest-bearing debt 609.6 580.8 5.0% 562.7 Gearing ratio (%) 88.4% 90.0% 84.7% Net debt/EBITDA * ** 3.0 3.1 2.9 Personnel at the end of period 341 413 -17.4% 434 * Annualized ** Current period restated without the IFRS 16 effects Reference period information does not include IFRS 16 effects 2 THE GASUM GROUP FINANCIAL RESULT FOR JANUARY 1 TO MARCH 2019 GASUM GROUP CEO JOHANNA LAMMINEN COMMENTS ON THE FIRST QUARTER OF 2019: ”Our financial performance was in line with our expectations during Q1. -

Annual Financial Statements 2017/18. Pursuant to Section 124 Stock Exchange Act 2018

EN Kapsch TrafficCom Annual Financial Statements 2017/18. Pursuant to Section 124 Stock Exchange Act 2018. Table of contents. 1. Consolidated Financial Statements as of March 31, 2018 Consolidated Financial Statements as of March 31, 2018 3 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 8 Management Report 76 Auditor’s Report 93 Statement of all Members of the Executive Board 98 2. Financial Statements as of March 31, 2018 Balance sheet as at March 31, 2018 100 Income statement for the fiscal year 2017/18 102 Notes to the financial statements for fiscal year 2017/18 103 Management Report as of March 31, 2018 119 Auditor’s Report 133 Statement of all Members of the Executive Board 140 Kapsch TrafficCom | 2 Consolidated Financial Statements as of March 31, 2018. Consolidated statement of comprehensive income. All amounts in EUR Note 2016/17 2017/18 Revenues (4) 648,479,213 693,256,518 Other operating income (5) 25,052,456 20,536,151 Changes in finished and unfinished goods and work in progress (6) 1,409,754 2,781,723 Other own work capitalized 3,551,874 404,489 Cost of materials and other production services (7) -242,146,257 -279,814,687 Staff costs (8) -224,169,884 -237,880,654 Amortization and depreciation (9) -17,715,773 -14,807,528 Other operating expenses (10) -134,359,527 -134,908,686 Proportional operating result of joint ventures (17) 0 492,120 Operating result 60,101,855 50,059,444 Finance income (11) 13,534,069 7,0 87,3 07 Finance costs (11) -13,147,130 -12,274,612 Financial result 386,940 -5,187,305 Results from associates and -

Consolidated Financial Statements

Consolidated Financial Statements SYMRISE AG, HOLZMINDEN JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 2019 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 2019 25. Other current non-financial liabilities 113 Consolidated Income Statement 70 26. Other current and non-current provisions 114 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive 27. Provisions for pensions and similar Income 71 obligations 114 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 72 28. Equity 120 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 74 29. Disclosures on capital management 123 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 75 30. Additional disclosures on the statement Notes 76 of cash flows 124 1. General information 76 31. Additional information on financial 2. Accounting policies 76 instruments and the measurement of 3. Segment information 96 fair value 126 4. Sales 100 32. Disclosures relating to financial 5. Cost of goods sold 100 instrument risk management 128 6. Personnel expenses 100 33. Contingent liabilities and other 7. Selling and marketing expenses 101 financial obligations 132 8. Research and development expenses 101 34. Transactions with related parties 133 9. Administration expenses 101 35. Executive Board and Supervisory Board 10. Other operating income 101 shareholdings 134 11. Financial result 102 36. Long-term objectives and methods 12. Income taxes 102 for managing financial risk 134 13. Amortization and depreciation 104 37. Audit of financial statements 134 14. Earnings per share 104 38. List of interests in entities 135 15. Cash and cash equivalents 105 39. Exemption from the obligation to 16. Trade receivables 105 prepare annual financial statements 17. Inventories 106 pursuant to Section 264 (3) of 18. Intangible assets 106 the German Commercial Code (HGB) 137 19. -

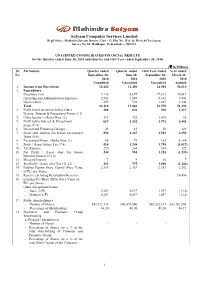

Mahindra Satyam Infocity, Unit - 12, Plot No

Satyam Computer Services Limited Regd Office: Mahindra Satyam Infocity, Unit - 12, Plot No. 35 & 36, Hi-tech City layout, Survey No. 64, Madhapur, Hyderabad — 500 081. UNAUDITED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL RESULTS for the Quarter ended June 30, 2010 and Quarter and Half Year ended September 30, 2010 ( ` In Million) Sl. Particulars Quarter ended Quarter ended Half Year ended Year ended No. September 30, June 30, September 30, March 31, 2010 2010 2010 2010 Unaudited Unaudited Unaudited Audited 1. Income from Operations 12,424 12,480 24,904 54,810 2. Expenditure Employee Cost 9,136 8,677 17,813 39,811 Operating and Administration Expenses 2,553 2,589 5,142 9,443 Depreciation 429 594 1,023 2,144 Total 12,118 11,860 23,978 51,398 3. Profit from Operations before Other 306 620 926 3,412 Income, Interest & Exceptional Items (1-2) 4. Other Income – (Refer Note 12) 313 732 1,045 69 5. Profit before Interest & Exceptional 619 1,352 1,971 3,481 Items (3+4) 6. Interest and Financing Charges 25 25 50 329 7. Profit after Interest but before Exceptional 594 1,327 1,921 3,152 Items (5-6) 8. Exceptional Items - (Refer Note 11) 84 79 163 4,169 9. Profit / (Loss) before Tax (7-8) 510 1,248 1,758 (1,017) 10. Tax Expense 270 264 534 222 11. Net Profit / (Loss) after Tax before 240 984 1,224 (1,239) Minority Interest (9-10) 12. Minority Interest 7 9 16 7 13. Net Profit / (Loss) after Tax (11-12) 233 975 1,208 (1,246) 14. -

The New Accounting Model of the Swiss Confederation

ISSN 1608-7143 OECD Journal on Budgeting Volume 8 – No. 1 © OECD 2008 The New Accounting Model of the Swiss Confederation by by The Federal Finance Administration* Switzerland’s public accounting system has been completely overhauled. The New Accounting Model for the Confederation was used for the first time to prepare the 2007 budget and the 2008-10 financial plan. This article examines the fundamental new directions of financial management in Switzerland. * This article was originally published in German in September 2006 and is available at www.efv.admin.ch. 1 THE NEW ACCOUNTING MODEL OF THE SWISS CONFEDERATION Executive summary In light of the growing demands on financial management, the decision was taken to overhaul the Swiss Confederation’s accounting system. The New Accounting Model (NAM) – in use for the first time in the 2007 budget and the 2008-10 financial plan – contains two fundamentally new approaches. First of all, the New Accounting Model takes a dual perspective in presenting the Confederation’s financial processes and circumstances. For overall fiscal policy management in accordance with the debt containment rule, which requires a balance between revenue and expenditure, the cash or financing aspect remains the focal point. This is conveyed in the financing and cash flow statement. However, in terms of administrative and operational management, the performance aspect now takes centre stage. As in the private sector, this is displayed in the income statement and supplemented with operational cost accounting. This makes a substantial contribution to ensuring the efficient and effective use of funds. Second, the Confederation’s financial reporting under the NAM is based on the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS), the only comprehensive and generally accepted set of guidelines for the public sector. -

Why Financial Statements Matter: Enforcement and Litigation Implications Breon S

an a.s. Pratt & sons Publication october 2013 Headnote: The new Problems Facing banks Steven A. Meyerowitz dealing witH civil investigative demands From tHe cFPb: rules, resPonses, and Practice considerations Joseph T. Lynyak III and Rebecca Tierney When talking Politics leads to Prison: Political intelligence & tHe STOCK act Kerry Burke, Robert Kelner, and Zachary Parks Why Financial statements matter: enForcement and litigation imPlications Breon S. Peace, Jonathan S. Kolodner, and Tamara J. Britt When is it too late For investors to bring RMBS-related claims? Joseph Cioffi and James R. Serritella is tHere a PatH tHrougH tHe woods? retention requirements For managed CLOs Kevin Ingram and Martin Sharkey unautHorized UCC Filings: a cautionary tale Marc Hanrahan and Sarah Griffin delaware bankruPtcy court Affirms lender’s ability to recover 37 Percent make- Whole Premium as Part oF its secured claim Luc A. Despins and G. Alexander Bongartz Caveat Cesso. tempus Fugit…. (creditors in bankruPtcy must beware delay, as time Flies) John D. Demmy The nature and Priority oF security under canada’s bank act Luciana Amaral banking brieFs Terence G. Banich editor-in-cHieF Steven A. Meyerowitz President, Meyerowitz Communications Inc. board oF editors Paul Barron Douglas Landy Elizabeth C. Yen Professor of Law Partner, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley Partner, Hudson Cook, LLP Tulane Univ. School of Law & McCloy LLP Bankruptcy for Bankers George Brandon Paul L. Lee Howard Seife Partner, Squire, Sanders & Of Counsel, Debevoise & Partner, Chadbourne & Parke Dempsey LLP Plimpton LLP LLP Barkley Clark Jonathan R. Macey Regional Banking Outlook Partner, Stinson Morrison Hecker Professor of Law James F. Bauerle LLP Yale Law School Keevican Weiss Bauerle & Hirsch LLC John F.