Unit 13 Response of Subnational Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

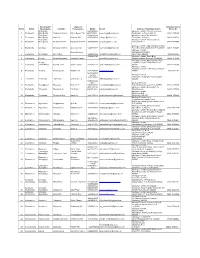

Payment Locations - Muthoot

Payment Locations - Muthoot District Region Br.Code Branch Name Branch Address Branch Town Name Postel Code Branch Contact Number Royale Arcade Building, Kochalummoodu, ALLEPPEY KOZHENCHERY 4365 Kochalummoodu Mavelikkara 690570 +91-479-2358277 Kallimel P.O, Mavelikkara, Alappuzha District S. Devi building, kizhakkenada, puliyoor p.o, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 4180 PULIYOOR chenganur, alappuzha dist, pin – 689510, CHENGANUR 689510 0479-2464433 kerala Kizhakkethalekal Building, Opp.Malankkara CHENGANNUR - ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 3777 Catholic Church, Mc Road,Chengannur, CHENGANNUR - HOSPITAL ROAD 689121 0479-2457077 HOSPITAL ROAD Alleppey Dist, Pin Code - 689121 Muthoot Finance Ltd, Akeril Puthenparambil ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2672 MELPADAM MELPADAM 689627 479-2318545 Building ;Melpadam;Pincode- 689627 Kochumadam Building,Near Ksrtc Bus Stand, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 2219 MAVELIKARA KSRTC MAVELIKARA KSRTC 689101 0469-2342656 Mavelikara-6890101 Thattarethu Buldg,Karakkad P.O,Chengannur, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1837 KARAKKAD KARAKKAD 689504 0479-2422687 Pin-689504 Kalluvilayil Bulg, Ennakkad P.O Alleppy,Pin- ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1481 ENNAKKAD ENNAKKAD 689624 0479-2466886 689624 Himagiri Complex,Kallumala,Thekke Junction, ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 1228 KALLUMALA KALLUMALA 690101 0479-2344449 Mavelikkara-690101 CHERUKOLE Anugraha Complex, Near Subhananda ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 846 CHERUKOLE MAVELIKARA 690104 04793295897 MAVELIKARA Ashramam, Cherukole,Mavelikara, 690104 Oondamparampil O V Chacko Memorial ALLEPPEY THIRUVALLA 668 THIRUVANVANDOOR THIRUVANVANDOOR 689109 0479-2429349 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 17.05.2020To23.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 17.05.2020to23.05.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr. No. 646/20 ERUMANGALATH H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 1 PHILIP JOSEPH JOSEPH 62 KUMARANALLOOR 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS PO, KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 BHAGAVATHY U/S MUHAMMED PARAMBIL H, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 2 ABDUL KHADER 52 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED BASHEER KARAPPUZHA PO, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KALAALAYAM H, U/S UNNIKRISHNA MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 3 BHASKARAN 58 PADINJAREMURY 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED N STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS BHAGOM, VAIKOM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 VILLATHARA H, U/S MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 4 SASI GOPALAKRISHNAN 44 NAGAMBADOM, 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS KOTTAYAM IPC & 4(2)(a) OF KEPDO Cr. No. 646/20 KOMALAPURAM H, U/S AVARMMA, MINI CIVIL 18.05.20 KOTTAYAM 5 SAJEEVAN RAKHAVAN NAIR 50 2336,269,188 SREEJITH T BAILED PERUMBADAVU, STATION 12:02 Hrs WEST PS IPC & 4(2)(a) KOTTAYAM OF KEPDO Cr. -

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - KOTTAYAM District, Kerala

Coconut Producers Federations (CPF) - KOTTAYAM District, Kerala Sl No.of No.of Bearing Annual CPF Reg No. Name of CPF and Contact address Panchayath Block Taluk No. CPSs farmers palms production Madappalli, FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES Thrikkodithanam, CHAGANASSERY WEST President: Shri Jose Mathew 1 CPF/KTM/2015-16/008 Payippad, Vazhappalli, Madappalli Changanassery 10 1339 40407 2002735 Iyyalil Vadakkelil, Madapalli PO, Kottayam Pin:686646 Kuruchi, Changanassery Mobile:7559080068 Municipality Kangazha, CHANGANASSERY REGIONAL FEDERATION OF Nedumkunnam, COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES President: V.J Vazhoor, 2 CPF/KTM/2013-14/001 Karukachal, Madappally, Changanassery 21 2268 69431 2531185 Varghese Thattaradiyil,Karukachal P.O Pin:686540 Madappally Vazhapally, Kurichi and Mobile:9388416569 Vakathanam REGIONAL FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS Vellavoor, Manimala, SOCIETY MANIMALA President: Shri Gopinatha Kurup Vazhoor,Kanjira Changanassery 3 CPF/KTM/2015-16/009 Vazhoor, Chirakadavu, 10 1425 40752 1133040 Puthenpurekkal Erathuvadakara P.O Manimala ppilly ,Kanjirappilly Elikkulam Pin:686543 Mobile:9447128232 FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES UPPER KUTTANADU President: Shri.P.V Jose 4 CPF/KTM/2015-16/017 Arpookkara, Neendoor Ettumanoor Kottayam 8 633 40986 1486162 Palamattam, Amalagiri P.O, Kottayam Pin:686561 Mobile:9496160954 Email:[email protected] KUMARAKOM FEDERATION OF COCONUT PRODUCERS SOCIETIES President: Jomon M.Joseph Kumarakom, Thiruvarp, 5 CPF/KTM/2014-15/003 Ettumanoor Kottayam 9 768 49822 2281625 Canal -

JULY \'13, 1998 Neendoor Njeezhoor PLI-Palal Palllkkathode Pappady

JULY \'13, 1998 2 3 4 5 6 7 Neendoor 552 456 408 133.38 1000 Lines Njeezhoor 552 514 712 126.79 1200 Lines PLI-Palal 5616 5080 764 1102.43 Nil Palllkkathode 1272 441 204 214.52 Nil Pappady 2575 2473 2305 271.56 2500 Lines Pampavalley 368 176 286 54.71 Nil Pathampuzha 368 181 125 49.39 Nil Perlngalam 528 362 230 81.44 Nil Pinnakkanadu 1216 1195 357 249.50 Nil Ponkunnam 1528 1516 1491 Nil 3500 Lines Poovarani 1000 990 783 199.75 2;;00 Lines Ramapuram 2500 1384 1408 565.06 Nil Talayolaparambu 2000 1498 630 524.33 Nil Teekoy 680 492 581 71.51 1104 Lines Uzhavoor 1400 987 809 96.63 2000 Lines VKM-Vaikom-I 4150 2468 988 606.59 Nil Vakathanam 1512 1478 1773 184.57 4000 Lines Valavoor 368 366 148 111.21 184 Lines Vazhoor 736 693 1516 229.56 2500 Lines Velichlyani 738 225 274 88.90 184 Lines National Monument at Kakorl memorials throughout India and ha~ recommended upgradation of existing schools and naming them after {Translation} freedom fighters. State GovtJUTs, however, have their own 3854. SHRI CHINMAYANAND SWAMI: scheme for honouring freedom fighters by construction of freedom memorials. SHRI SHANKER PRASAD JAISWAL: NatIonal Highway Link at Canacona Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: [English} (a) whether the Government are contemplating any 3855. SHRI FRANCISCO SARDINHA: Will the Minister scheme to declare the place of birth and work of people who of SURFACE TRANSPORT be pleased to state: died as martyrs during freedom struggle In Kakori event as national monument or for their development; (a) the distance In kilometers between Karwar-Madgao after the National Highway link at Canacona Is completed; (b) If so, the details thereof; and (bj the progress made in the construction of bridges and (c) If not, the reasons therefor? the link road; and THE MINISTER OF HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOP- (c) the steps taken by the Govemment to speed up the MENT AND MINISTER OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY project? (DR. -

2562263 [email protected] PD ATMA

SL No Office Name Address Telephone Number Email-ID Principal Agricultural Officer, Collectorate P.O, 1 Principal Agricultural Office 0481- 2562263 [email protected] kottayam 2 PD ATMA Project Director ATMA, Collectorate P.O, kottayam 0481- 2560569 [email protected] Assistant Director of Agriculture ,Municipal Rest 3 ADA Kottayam 9496000840 [email protected] House Building, Near Boat Jetty, Kottayam - 1 Agriculture Officer,Nattakom Krishibhavan , 4 Krishibhavan Nattakom 0481- 2360105 [email protected] Mariappally P.O PIN 686023 Agriculture Officer,Vijayapuram Krishibhavan , 5 Krishibhavan Vijayapuram 0481-2578060 [email protected] Vadavathoor P.O, Kottayam PIN 686010 Agriculture Officer,Ayarkunnam Krishibhavan , 6 Krishibhavan Ayarkkunnam 0481- 2546133 [email protected] Arumanoor P.O PIN 686509 Agriculture Officer, Puthuppally Krishibhavan 7 Krishibhavan Puthuppally 9496000845 [email protected] Eravilnalloor P.O, Kottayam- 686011 Agriculture Officer, Panachikkad Krishibhavan 8 Krishibhavan Panachikkad Kuzhimattom P.O, Paruthumpara, Kottayam- 0481- 24330353 [email protected] 686533 Agriculture Officer, Krishibhavan ,Kumaranalloor 9 Krishibhavan Kumaranalloor 0481- 2310466 [email protected] P.O, Kottayam- 686016 Agriculture Officer, Krishibhavan ,Kurichy P.O, 10 KrishiBhavan Kurichy 0481-2320307 [email protected] Kottayam- 686532 Agricultural Field Officer, KrishiBhavan Kottayam 11 KrishiBhavan Kottayam(M) Municipality ,Municipal Rest House Building,Near 9496000848 [email protected] Boat -

Sl.No. Block Location Mobile E-Mail Address of Akshaya Centre 1 Erattupetta Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M [email protected]

Panchayath/ Name of Akshaya Centre Sl.No. Block Municipality Location Entrepreneur Mobile E-mail Address of Akshaya Centre Phone No Erattupetta 9961985088, Akshaya e centre, Chennadu Kavala, 1 Erattupetta Municipality Chennadu Kavala Sajida Beevi. T.M 9447507691, [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam-686121 04822-275088 Erattupetta 9446923406, Akshaya e centre, Nadackal P O, 2 Erattupetta Municipality Hutha Jn. Shaheer PM 9847683049 [email protected] Erattupetta, Kottayam 04822-329714 Erattupetta Akshaya e centre, Thottumukku Jn., 3 Erattupetta Municipality Thottumukku Jn. Rasiya M Shereef 9847095886 [email protected] Erattupetta P O 04828-277550 Akshaya e centre, Opp. Melukavumattom 4 Erattupetta Melukavu Melukavu Mattom Anoop Mohan 9447515722 [email protected] Post office,Melukavumattom P O,686652 04822-220402 Akshaya e-centre, Minimol Antony Punnathaniyil Building 5 Erattupetta Moonnilavu Moonnilavu 9446861799 [email protected] Moonnilavu-686596 48222-86266 9745402710 Akshaya e centre, Chalil Bldg, 6 Erattupetta Poonjar Panachikkappara Aniamma Suresh [email protected] Panachikkapara, Poonjar P O-686581 04822-276506 Akshaya e centre, Panchayathu office Poonjar Complex,Poonjar Thekkekkara P O- 7 Erattupetta Thekkekkara Poonjar Town Shymol Jacob 9745402710 [email protected] 686582 04822-276506 Akshaya e centre, Panchayat Junction, Theekoy, Kottayam- 8 Erattupetta Teekkoy Panchayat Jn. Sulfath K H 9400233778 [email protected] 686581 48222-81145 9847093283 Suresh- Akshaya e-centre, 8547672267 Thalanadu, Thalanadu -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 09.08.2020To15.08.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 09.08.2020to15.08.2020 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 CHEMBAKA NELOOR CR.643/20 U/S KABEER KP SI VADAKKETHIL HOUSE 15.08.2020- 188,269,336 Kottayam 1 BIJUMON V VELUKUTTY M-40 MANGANAM KOTTAYAM BAIL FROM PS MANGANAM 17.00 HRS IPC & 4(2)(d) east EAST KOTTAYAM KEDO ACT CR.643/20 U/S THADATHIL HOUSE KABEER KP SI 15.08.2020- 188,269,336 Kottayam 2 SABITH TS SABU M-29 ERICADU PO MANGANAM KOTTAYAM BAIL FROM PS 17.00 HRS IPC & 4(2)(d) east KOTTAYAM EAST KEDO ACT 487/2020-U/S NELLIMMOOTTIL K.R CHANDY 10.8.2020- 354(A)(1)IPC& JFMC 3 NC ABRAHAM 68/M HOUSE, AYARKUNNAM AYARKUNNAM HARIKUMAR- ABRAHAM 10.45.HRS. 7&8 OF POCSO KOTTAYAM AYARKUNNAM SI OF POLICE ACT. Cherivuparambil House, Morkulangara, 1009 U/S Male 10-08-2020 Changanasser Sreekumar T N 4 Shiji Gopalan Rubi Nagar P.O., Morkulangara 118(a) of KP BAIL FROM PS 46 14:45 y S I Of POLICE Vazhappally East, Act Changanacherry Cheethuthara House, 1010 U/S 269, Kunnamkari Temple 336, 188 IPC & Gopalakrishna Parameswara Male Changanacherr 11-08-2020 Changanasser Shameer Khan, 5 Bhagam, Kunnumkari Sec 4(2)(e)(j) BAIL FROM PS n n Pillai 54 y Market 10:30 y SI of Police P.O, Veliyambra r/w 3(a)(f)(g) Village of KEDO -2020 Tom Mathew, 1012 U/S 188, Changanacherr SI of Police, Male Sundhra Bhavan, 11-08-2020 -

From, George Joseph, (Applicant) Kozhuppankutty House, Marangoly P.O., Kottayam, Kerala – 686612

From, George Joseph, (Applicant) Kozhuppankutty House, Marangoly P.O., Kottayam, Kerala – 686612 To, The chairman, Dt. 10-10-2017 District Environment Impact Assessment Authority, Kottayam, Kerala. Ref: - 1. DIA/KL/MIN/5513/2017 2. K22/DEIAA/Q20/17 3. Minutes of DEAC, Kottayam held on 28-07-2017 Sub: - Environmental Clearance – Quarry Project at Survey Nos. 132/3-1, 132/3, 132/5, 132/5-1, 132/6, 132/7, 132/2, 129/3, Njeezhoor Village, Vaikom Taluk, Kottayam District, Kerala – Submission of additional documents – Reg. Respected Sir, This refers to the application submitted for obtaining Environmental Clearance for proposed building stone quarry at Njeezhoor Village, Vaikom Taluk, Kottayam District, Kerala. A field inspection was carried out by DEAC. Subsequently, a meeting of DEAC was held on 28-07-2017. From the minutes of the meeting, it is observed that the committee raised a concern regarding the existence of a building which is located at a distance of about 30m from the mining area. It may be noted that the said building is not used for residential purposes and it is only used as store room to keep the equipments related to the quarry. To establish this fact, we hereby submit the following documents for your kind consideration. (1) An affidavit stating that the said building is used as a store room is attached as Annexure No. 1. (2) The project proponent has been paying commercial tax for said building. The latest copy of commercial tax receipt is attached as Annexure No. 2. (3) This building structure falls within 100 meters from the proposed project site and the same is marked in the survey map which is duly signed by village officer and Tahsildar. -

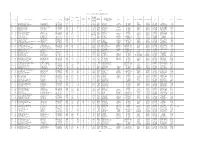

Sheet1 Page 1 LIST of SCHOOLS in KOTTAYAM DISTRICT 10 Sl. No

Sheet1 LIST OF SCHOOLS IN KOTTAYAM DISTRICT No of Students HS/HSS/ Year of VHSS/H Name of Panch- Std. Std. Boys/ 10 Sl. No. Name of School Address with Pincode Phone No Establishm SS ayat /Muncipality/ Block Taluk Name of Parliament Name of Assembly DEO AEO MGT Remarks (From) (To) Girls/ Mixed ent Boys Girls &VHSS/ Corporation TTI 10 1 Areeparambu Govt. HSS Areeparambu P.O. 0481-2700300 1905 42 36 I XII HSS Mixed Manarcadu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 2 Arpookara Medical College VHSS Gandhinagar P.O. 0481-2597401 1966 73 33 V XII HSS&VHSS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 3 Changanacherry Govt. HSS Changanacherry P.O. 0481-2420748 1871 43 23 V XII HSS Mixed Changanacherry ( M ) Changanacherry Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Changanassery Govt 10 4 Chengalam Govt. HSS Chengalam South P.O. 0481-2524828 1917 127 107 I XII HSS Mixed Thiruvarpu Pallam Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 5 Karapuzha Govt. HSS Karapuzha P.O. 0481-2582936 1895 56 34 I XII HSS Mixed Kottayam( M ) Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 6 Karipputhitta Govt. HS Arpookara P.O. 0481-2598612 1915 74 44 I X HS Mixed Arpookara Ettumanoor Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Kottayam West Govt 10 7 Kothala Govt. VHSS S.N. Puram P.O. 0481-2507726 1912 48 64 I XII VHSS Mixed Kooroppada Pampady Kottayam Err:514 Err:514 Kottayam Pampady Govt 10 8 Kottayam Govt. -

25973 1971 ADM.Pdf

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES--9 KERALA PART IX-A ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS K. NARAYANAN OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 1976 3/19-i FOREWORD In order to ensure complete coverage at a population count, the Census Organization obtains or prepares up-to-date detailed maps of all administrative units in the country on the eve of a census. Though in several parts of the country maps of the districts, taluks etc., are available with the State Revenue or Survey authorities, often times, they required to be brought up-to-date and they also varied greatly in scale. One also found it difficult to secure a complete or compact set of all these maps from State authorities. The Census Organization took upon itself the task of updating of the administrative maps and the standadization of scales essentially to meet its own requirements of coverage at the census and analysis of data. Standardization of symbol was also attempted to depict certain features such as the Statejdistrictjtaluk boundades, administrative headquarters, national and state highways and other roads, markets and mandis, post and telegraph offices, travellers' bungalows, hospitals, etc. In each of the District Census Handbooks (there are 356 districts in the country) the district map as wdl as the taluk maps will be printed. While these administrative maps, prepared with great amount of care and effort, served the purposes of the census extremely well, the 1971 Census Organization felt that these would be invaluable for many an administrative purpose and for planning and also to the scholars who might like t~! utilize these maps for various studies. -

Kottayam District Disaster Management Plan

District Disaster Management Plan, 2015 Kottayam District Disaster Management Plan Published under Section 30 (2) (i) of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (Central Act 53 of 2005) District Disaster Management Plan 2015 30th July 2016; Pages: 136 District This document is for official purposes only. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the District Disaster Management Authority to verify the information and ensure stakeholder consultation and inputs prior to publication of this document. The publisher welcomes suggestions for improved future editions. District Disaster Management Plan – KOTTAYAM 2015 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 VISION ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 MISSION ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 POLICY ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE PLAN ................................................................................................................................................ -

Accused Persons Arrested in Kottayam District from 23.05.2021To29.05.2021 Name of Name of Arresting Name of the Place at Date & the Court Sl

Accused Persons arrested in Kottayam district from 23.05.2021to29.05.2021 Name of Name of Arresting Name of the Place at Date & the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Address of Cr. No & Sec Police Officer, father of which Time of at which No. Accused Sex Accused of Law Station Rank & Accused Arrested Arrest accused Designatio produced n 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 HARIKRISHNAN MANOJ T K, HOUSE COLLECTORAT 24.05.2021, CR.1034/21,18 Kottayam SI OF POLI BAIL FROM 1 SUJITH SURENDRAN M-40 VETTATHUKAVALA E 08.40 HRS 8 IPC& KEDO east KOTTAYAM PS PUTHUPALLY EAST.P.S MANOJ T K, KOCHUKAITHAYIL CR 1035/21 RAMACHAND 24.05.2021, Kottayam SI OF POLI BAIL FROM 2 JAYAN M-59 HOUSE,PUTHUPALLY PUTHUPPALLY U/S 188 IPC& RAN 12.50 HRS east KOTTAYAM PS KOTTAYAM KEDO EAST.P.S KONDODICKEL CR 1036/21 ROOPESH 24.05.2021, Kottayam BAIL FROM 3 JAIMINI JOSE JOSE M-59 HOUSE KANJIKUZHY KANJIKUZHY U/S188IPC& K.R SI 13.30 HRS east PS KOTTAYAM KEDO KOTTAYAM BEJOY.P.T.IN PUTHUPARAMBIL CR 1037/21 SPECTOR OF AKHIL S HOUSE, 24.05.2021- Kottayam BAIL FROM 4 GEORGE M-39 PUTHUPPALLY U/S 188IPC& POLICE GEORGE KANJIRATHUMOOD 20.15 HRS east PS KEDO KOTTAYAM PUTHUPALLY EAST.P.S BINUMON.P. NEDUNGOTTUMALA CR 1040/21 C SI OF KRISHNANKUT COLLECTORAT 25.05.2021, Kottayam BAIL FROM 5 AKHIL M-31 HOUSE KUTTICKAL U/S 188 IPC& POLICE TY E 8.00 HRS east PS PAMPADY KEDO KOTTAYAM EAST.P.S BINUMON.P.