Guidelines for the Secure Deployment of Ipv6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 10: Switching & Internetworking

Lecture 10: Switching & Internetworking CSE 123: Computer Networks Alex C. Snoeren HW 2 due WEDNESDAY Lecture 10 Overview ● Bridging & switching ◆ Spanning Tree ● Internet Protocol ◆ Service model ◆ Packet format CSE 123 – Lecture 10: Internetworking 2 Selective Forwarding ● Only rebroadcast a frame to the LAN where its destination resides ◆ If A sends packet to X, then bridge must forward frame ◆ If A sends packet to B, then bridge shouldn’t LAN 1 LAN 2 A W B X bridge C Y D Z CSE 123 – Lecture 9: Bridging & Switching 3 Forwarding Tables ● Need to know “destination” of frame ◆ Destination address in frame header (48bit in Ethernet) ● Need know which destinations are on which LANs ◆ One approach: statically configured by hand » Table, mapping address to output port (i.e. LAN) ◆ But we’d prefer something automatic and dynamic… ● Simple algorithm: Receive frame f on port q Lookup f.dest for output port /* know where to send it? */ If f.dest found then if output port is q then drop /* already delivered */ else forward f on output port; else flood f; /* forward on all ports but the one where frame arrived*/ CSE 123 – Lecture 9: Bridging & Switching 4 Learning Bridges ● Eliminate manual configuration by learning which addresses are on which LANs Host Port A 1 ● Basic approach B 1 ◆ If a frame arrives on a port, then associate its source C 1 address with that port D 1 ◆ As each host transmits, the table becomes accurate W 2 X 2 ● What if a node moves? Table aging Y 3 ◆ Associate a timestamp with each table entry Z 2 ◆ Refresh timestamp for each -

Efficient, Dos-Resistant, Secure Key Exchange

Efficient, DoS-Resistant, Secure Key Exchange for Internet Protocols∗ William Aiello Steven M. Bellovin Matt Blaze AT&T Labs Research AT&T Labs Research AT&T Labs Research [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Ran Canetti John Ioannidis Angelos D. Keromytis IBM T.J. Watson Research Center AT&T Labs Research Columbia University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Omer Reingold AT&T Labs Research [email protected] Categories and Subject Descriptors While it might be possible to “patch” the IKE protocol to fix C.2.0 [Security and Protection]: Key Agreement Protocols some of these problems, it may be perferable to construct a new protocol that more narrorwly addresses the requirements “from the ground up.” We set out to engineer a new key exchange protocol General Terms specifically for Internet security applications. We call our new pro- Security, Reliability, Standardization tocol “JFK,” which stands for “Just Fast Keying.” Keywords 1.1 Design Goals We seek a protocol with the following characteristics: Cryptography, Denial of Service Attacks Security: No one other than the participants may have access to ABSTRACT the generated key. We describe JFK, a new key exchange protocol, primarily designed PFS: It must approach Perfect Forward Secrecy. for use in the IP Security Architecture. It is simple, efficient, and secure; we sketch a proof of the latter property. JFK also has a Privacy: It must preserve the privacy of the initiator and/or re- number of novel engineering parameters that permit a variety of sponder, insofar as possible. -

Network Access Control and Cloud Security

Network Access Control and Cloud Security Raj Jain Washington University in Saint Louis Saint Louis, MO 63130 [email protected] Audio/Video recordings of this lecture are available at: http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-17/ Washington University in St. Louis http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-17/ ©2017 Raj Jain 16-1 Overview 1. Network Access Control (NAC) 2. RADIUS 3. Extensible Authentication Protocol (EAP) 4. EAP over LAN (EAPOL) 5. 802.1X 6. Cloud Security These slides are based partly on Lawrie Brown’s slides supplied with William Stallings’s book “Cryptography and Network Security: Principles and Practice,” 7th Ed, 2017. Washington University in St. Louis http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-17/ ©2017 Raj Jain 16-2 Network Access Control (NAC) AAA: Authentication: Is the user legit? Supplicant Authenticator Authentication Server Authorization: What is he allowed to do? Accounting: Keep track of usage Components: Supplicant: User Authenticator: Network edge device Authentication Server: Remote Access Server (RAS) or Policy Server Backend policy and access control Washington University in St. Louis http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-17/ ©2017 Raj Jain 16-3 Network Access Enforcement Methods IEEE 802.1X used in Ethernet, WiFi Firewall DHCP Management VPN VLANs Washington University in St. Louis http://www.cse.wustl.edu/~jain/cse571-17/ ©2017 Raj Jain 16-4 RADIUS Remote Authentication Dial-In User Service Central point for Authorization, Accounting, and Auditing data ⇒ AAA server Network Access servers get authentication info from RADIUS servers Allows RADIUS Proxy Servers ⇒ ISP roaming alliances Uses UDP: In case of server failure, the request must be re-sent to backup ⇒ Application level retransmission required TCP takes too long to indicate failure Proxy RADIUS RADIUS Network Remote Access User Customer Access ISP Net Server Network Server Ref: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RADIUS Washington University in St. -

Wifi Direct Internetworking

WiFi Direct Internetworking António Teólo∗† Hervé Paulino João M. Lourenço ADEETC, Instituto Superior de NOVA LINCS, DI, NOVA LINCS, DI, Engenharia de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa Universidade NOVA de Lisboa Universidade NOVA de Lisboa Portugal Portugal Portugal [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT will enable WiFi communication range and speed even in cases of: We propose to interconnect mobile devices using WiFi-Direct. Hav- network infrastructure congestion, which may happen in highly ing that, it will be possible to interconnect multiple o-the-shelf crowded venues (such as sports and cultural events); or temporary, mobile devices, via WiFi, but without any supportive infrastructure. or permanent, absence of infrastructure, as may happen in remote This will pave the way for mobile autonomous collaborative sys- locations or disaster situations. tems that can operate in any conditions, like in disaster situations, WFD allows devices to form groups, with one of them, called in very crowded scenarios or in isolated areas. This work is relevant Group Owner (GO), acting as a soft access point for remaining since the WiFi-Direct specication, that works on groups of devices, group members. WFD oers node discovery, authentication, group does not tackle inter-group communication and existing research formation and message routing between nodes in the same group. solutions have strong limitations. However, WFD communication is very constrained, current imple- We have a two phase work plan. Our rst goal is to achieve mentations restrict group size 9 devices and none of these devices inter-group communication, i.e., enable the ecient interconnec- may be a member of more than one WFD group. -

The Internet in Iot—OSI, TCP/IP, Ipv4, Ipv6 and Internet Routing

Chapter 2 The Internet in IoT—OSI, TCP/IP, IPv4, IPv6 and Internet Routing Reliable and efficient communication is considered one of the most complex tasks in large-scale networks. Nearly all data networks in use today are based on the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) standard. The OSI model was introduced by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in 1984, to address this composite problem. ISO is a global federation of national standards organizations representing over 100 countries. The model is intended to describe and standardize the main communication functions of any telecommunication or computing system without regard to their underlying internal structure and technology. Its goal is the interoperability of diverse communication systems with standard protocols. The OSI is a conceptual model of how various components communicate in data-based networks. It uses “divide and conquer” concept to virtually break down network communication responsibilities into smaller functions, called layers, so they are easier to learn and develop. With well-defined standard interfaces between layers, OSI model supports modular engineering and multivendor interoperability. 2.1 The Open Systems Interconnection Model The OSI model consists of seven layers as shown in Fig. 2.1: physical (Layer 1), data link (Layer 2), network (Layer 3), transport (Layer 4), session (Layer 5), presentation (Layer 6), and application (Layer 7). Each layer provides some well-defined services to the adjacent layer further up or down the stack, although the distinction can become a bit less defined in Layers 6 and 7 with some services overlapping the two layers. • OSI Layer 7—Application Layer: Starting from the top, the application layer is an abstraction layer that specifies the shared protocols and interface methods used by hosts in a communications network. -

Ipv6-Ipsec And

IPSec and SSL Virtual Private Networks ITU/APNIC/MICT IPv6 Security Workshop 23rd – 27th May 2016 Bangkok Last updated 29 June 2014 1 Acknowledgment p Content sourced from n Merike Kaeo of Double Shot Security n Contact: [email protected] Virtual Private Networks p Creates a secure tunnel over a public network p Any VPN is not automagically secure n You need to add security functionality to create secure VPNs n That means using firewalls for access control n And probably IPsec or SSL/TLS for confidentiality and data origin authentication 3 VPN Protocols p IPsec (Internet Protocol Security) n Open standard for VPN implementation n Operates on the network layer Other VPN Implementations p MPLS VPN n Used for large and small enterprises n Pseudowire, VPLS, VPRN p GRE Tunnel n Packet encapsulation protocol developed by Cisco n Not encrypted n Implemented with IPsec p L2TP IPsec n Uses L2TP protocol n Usually implemented along with IPsec n IPsec provides the secure channel, while L2TP provides the tunnel What is IPSec? Internet IPSec p IETF standard that enables encrypted communication between peers: n Consists of open standards for securing private communications n Network layer encryption ensuring data confidentiality, integrity, and authentication n Scales from small to very large networks What Does IPsec Provide ? p Confidentiality….many algorithms to choose from p Data integrity and source authentication n Data “signed” by sender and “signature” verified by the recipient n Modification of data can be detected by signature “verification” -

Mist Teleworker ME

MIST TELEWORKER GUIDE Experience the corporate network @ home DOCUMENT OWNERS: Robert Young – [email protected] Slava Dementyev – [email protected] Jan Van de Laer – [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Solution Overview 3 How it works 5 Configuration Steps 6 Setup Mist Edge 6 Configure and prepare the SSID 15 Enable Wired client connection via ETH1 / Module port of the AP 16 Enable Split Tunneling for the Corp SSID 17 Create a Site for Remote Office Workers 18 Claim an AP and ship it to Employee’s location 18 Troubleshooting 20 Packet Captures on the Mist Edge 23 2 Solution Overview Mist Teleworker solution leverages Mist Edge for extending a corporate network to remote office workers using an IPSEC secured L2TPv3 tunnel from a remote Mist AP. In addition, MistEdge provides an additional RadSec service to securely proxy authentication requests from remote APs to provide the same user experience as inside the office. WIth Mist Teleworker solution customers can extend their corporate WLAN to employee homes whenever they need to work remotely, providing the same level of security and access to corporate resources, while extending visibility into user network experience and streamlining IT operations even when employees are not in the office. What are the benefits of the Mist Teleworker solution with Mist Edge compared to all the other alternatives? Agility: ● Zero Touch Provisioning - no AP pre-staging required, support for flexible all home coverage with secure Mesh ● Exceptional support with minimal support - leverage Mist SLEs and Marvis Actions Security: ● Traffic Isolation - same level of traffic control as in the office. -

Performance Analysis and Comparison of 6To4 Relay Implementations

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 4, No. 9, 2013 Performance Analysis and Comparison of 6to4 Relay Implementations Gábor Lencse Sándor Répás Department of Telecommunications Department of Telecommunications Széchenyi István University Széchenyi István University Győr, Hungary Győr, Hungary Abstract—the depletion of the public IPv4 address pool may delegated the last five “/8” IPv4 address blocks to the five speed up the deployment of IPv6. The coexistence of the two Regional Internet Registries in 2011 [3]. Therefore an versions of IP requires some transition mechanisms. One of them important upcoming coexistence issue is the problem of an is 6to4 which provides a solution for the problem of an IPv6 IPv6 only client and an IPv4 only server, because internet capable device in an IPv4 only environment. From among the service providers (ISPs) can still supply the relatively small several 6to4 relay implementations, the following ones were number of new servers with IPv4 addresses from their own selected for testing: sit under Linux, stf under FreeBSD and stf pool but the huge number of new clients can get IPv6 addresses under NetBSD. Their stability and performance were investigat- only. DNS64 [4] and NAT64 [5] are the best available ed in a test network. The increasing measure of the load of the techniques that make it possible for an IPv6 only client to 6to4 relay implementations was set by incrementing the number communicate with an IPv4 only server. Another very important of the client computers that provided the traffic. The packet loss and the response time of the 6to4 relay as well as the CPU coexistence issue comes from the case when the ISP does not utilization and the memory consumption of the computer support IPv6 but the clients do and they would like to running the tested 6to4 relay implementations were measured. -

Routing Loop Attacks Using Ipv6 Tunnels

Routing Loop Attacks using IPv6 Tunnels Gabi Nakibly Michael Arov National EW Research & Simulation Center Rafael – Advanced Defense Systems Haifa, Israel {gabin,marov}@rafael.co.il Abstract—IPv6 is the future network layer protocol for A tunnel in which the end points’ routing tables need the Internet. Since it is not compatible with its prede- to be explicitly configured is called a configured tunnel. cessor, some interoperability mechanisms were designed. Tunnels of this type do not scale well, since every end An important category of these mechanisms is automatic tunnels, which enable IPv6 communication over an IPv4 point must be reconfigured as peers join or leave the tun- network without prior configuration. This category includes nel. To alleviate this scalability problem, another type of ISATAP, 6to4 and Teredo. We present a novel class of tunnels was introduced – automatic tunnels. In automatic attacks that exploit vulnerabilities in these tunnels. These tunnels the egress entity’s IPv4 address is computationally attacks take advantage of inconsistencies between a tunnel’s derived from the destination IPv6 address. This feature overlay IPv6 routing state and the native IPv6 routing state. The attacks form routing loops which can be abused as a eliminates the need to keep an explicit routing table at vehicle for traffic amplification to facilitate DoS attacks. the tunnel’s end points. In particular, the end points do We exhibit five attacks of this class. One of the presented not have to be updated as peers join and leave the tunnel. attacks can DoS a Teredo server using a single packet. The In fact, the end points of an automatic tunnel do not exploited vulnerabilities are embedded in the design of the know which other end points are currently part of the tunnels; hence any implementation of these tunnels may be vulnerable. -

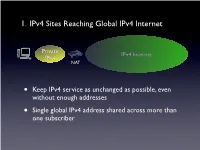

1. Ipv4 Sites Reaching Global Ipv4 Internet

1. IPv4 Sites Reaching Global IPv4 Internet Private IPv4 Internet IPv4 NAT • Keep IPv4 service as unchanged as possible, even without enough addresses • Single global IPv4 address shared across more than one subscriber SP IPv6 Network Private Tunnel for IPv4 (public, private, port-limited, etc....) IPv4 Internet IPv4 • Scenario #2 - Service Providers Running out of Private IPv4 space • IPv4 / IPv6 encapsulations/tunnels • Tunnels setup by DHCP, Routing, etc. between a GW and Router • Wherever the NAT lands, it is important that the user keeps control of it • Provides a path to delivering IPv6 SP IPv6 Network Tunnel for IPv4 (public, private, port-limited, etc....) IPv4 Internet • Scenario #3a “Wireless Greenfield” • IPv4 / IPv6 encapsulations/tunnels • Tunnels setup between a host and a Router • IPv4 binding for host applications, transport over IPv6 • Wherever the NAT lands, it is important that the user keeps control of it 3 - 5 Translation Options IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet IPv6 IPv4 My IPv6 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #3” • NAT64/DNS64.... - Stateful, DNSSEC Challenges, DNS64 location, etc. My IPv6 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #5” • IVI - NAT-PT..... Expose only certain IPv6 servers, etc. MY IPv4 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • “Scenario #4” • NAT64 - 1:1, Stateless, DNSSEC OK, no DNS64 MY IPv4 Network IPv6 Internet IPv4 Internet • Already solved by existing transition mechanisms?? (teredo, etc). Scenarios 1 - 5 1. IPv4 Sites Reaching Global IPv4 Internet Private IPv4 Internet IPv4 NAT • Keep IPv4 service as unchanged as possible, even without enough addresses • Single global IPv4 address shared across more than one subscriber 2. Service Providers Running out of Private IPv4 space ISP Private IPv4 Private Network IPv4 IPv4 Internet • Service Providers with large, privately addressed, IPv4 networks • Organic growth plus pressure to free global addresses for customer use contribute to the problem • The SP Private networks in question generally do not need to reach the Internet at large 3. -

Host Identity Protocol (HIP) •Overlays (I3 and Hi3) •Summary Introductionintroduction

HostHost IdentityIdentity ProtocolProtocol Prof. Sasu Tarkoma 23.02.2009 Part of the material is based on lecture slides by Dr. Pekka Nikander (HIP) and Dmitrij Lagutin (PLA) ContentsContents •Introduction •Current state •Host Identity Protocol (HIP) •Overlays (i3 and Hi3) •Summary IntroductionIntroduction •Current Internet is increasingly data and content centric •The protocol stack may not offer best support for this •End-to-end principle is no longer followed – Firewalls and NAT boxes – Peer-to-peer and intermediaries •Ultimately, hosts are interested in receiving valid and relevant information and do not care about IP addresses or host names •This motivate the design and development of new data and content centric networking architectures – Related work includes ROFL, DONA, TRIAD, FARA, AIP, .. TheThe InternetInternet hashas ChangedChanged •A lot of the assumptions of the early Internet has changed – Trusted end-points – Stationary, publicly addressable addresses – End-to-End •We will have a look at these in the light of recent developments •End-to-end broken by NATs and firewalls HTTPS, S/MIME, PGP,WS-Security, Radius, Diameter, SAML 2.0 .. Application Application Transport TSL, SSH, .. Transport HIP, shim layers IPsec, PLA, PSIRP Network Network PAP, CHAP, WEP, .. Link Link Physical Physical CurrentCurrent StateState TransportTransport LayerLayer IP layer IP layer Observations IPsec End-to-end reachability is broken Routing Unwanted traffic is a problem Fragmentation Mobility and multi-homing are challenging Multicast is difficult -

Lecture: TCP/IP 2

TCP/IP- Lecture 2 [email protected] How TCP/IP Works • The four-layer model is a common model for describing TCP/IP networking, but it isn’t the only model. • The ARPAnet model, for instance, as described in RFC 871, describes three layers: the Network Interface layer, the Host-to- Host layer, and the Process-Level/Applications layer. • Other descriptions of TCP/IP call for a five-layer model, with Physical and Data Link layers in place of the Network Access layer (to match OSI). Still other models might exclude either the Network Access or the Application layer, which are less uniform and harder to define than the intermediate layers. • The names of the layers also vary. The ARPAnet layer names still appear in some discussions of TCP/IP, and the Internet layer is sometimes called the Internetwork layer or the Network layer. [email protected] 2 [email protected] 3 TCP/IP Model • Network Access layer: Provides an interface with the physical network. Formats the data for the transmission medium and addresses data for the subnet based on physical hardware addresses. Provides error control for data delivered on the physical network. • Internet layer: Provides logical, hardware-independent addressing so that data can pass among subnets with different physical architectures. Provides routing to reduce traffic and support delivery across the internetwork. (The term internetwork refers to an interconnected, greater network of local area networks (LANs), such as what you find in a large company or on the Internet.) Relates physical addresses (used at the Network Access layer) to logical addresses.