Brain Sciences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12 Retina Gabriele K

299 12 Retina Gabriele K. Lang and Gerhard K. Lang 12.1 Basic Knowledge The retina is the innermost of three successive layers of the globe. It comprises two parts: ❖ A photoreceptive part (pars optica retinae), comprising the first nine of the 10 layers listed below. ❖ A nonreceptive part (pars caeca retinae) forming the epithelium of the cil- iary body and iris. The pars optica retinae merges with the pars ceca retinae at the ora serrata. Embryology: The retina develops from a diverticulum of the forebrain (proen- cephalon). Optic vesicles develop which then invaginate to form a double- walled bowl, the optic cup. The outer wall becomes the pigment epithelium, and the inner wall later differentiates into the nine layers of the retina. The retina remains linked to the forebrain throughout life through a structure known as the retinohypothalamic tract. Thickness of the retina (Fig. 12.1) Layers of the retina: Moving inward along the path of incident light, the individual layers of the retina are as follows (Fig. 12.2): 1. Inner limiting membrane (glial cell fibers separating the retina from the vitreous body). 2. Layer of optic nerve fibers (axons of the third neuron). 3. Layer of ganglion cells (cell nuclei of the multipolar ganglion cells of the third neuron; “data acquisition system”). 4. Inner plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the second neuron and dendrites of the third neuron). 5. Inner nuclear layer (cell nuclei of the bipolar nerve cells of the second neuron, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells). 6. Outer plexiform layer (synapses between the axons of the first neuron and dendrites of the second neuron). -

Background to the Celebration of Herbert D. Kleber (1904 -2018) by Thomas A

1 Background to the Celebration of Herbert D. Kleber (1904 -2018) by Thomas A. Ban By the mid-1990s the pioneering generation in neuropsychopharmacology was fading away. To preserve their legacy the late Oakley Ray (1931-2007), at the time Secretary of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP), generated funds from Solway Pharmaceuticals for the founding of the ACNP-Solway Archives in Neuropsychopharmacology. Ray also arranged for the videotaping of interviews (mainly by their peers) with the pioneers, mostly at annual meetings, to be stored in the archives. Herbert Kleber was interviewed by Andrea Tone, a medical historian at the Annual Meeting of the College held in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on December 7, 2003 (Ban 2011a; Kleber 2011a). The endeavor that was to become known as the “oral history project” is based on 235 videotaped interviews conducted by 66 interviewers with 213 interviewees which, on the basis of their content, were divided and edited into a 10-volume series produced by Thomas A. Ban, in collaboration with nine colleagues who were to become volume editors. One of them, Herbert Kleber, was responsible for the editing of Volume Six, dedicated to Addiction (Kleber 2011b). The series was published by the ACNP with the title “An Oral History of Neuropsychopharmacology Peer Interviews The First Fifty Years” and released at the 50th Anniversary Meeting of the College in 2011 (Ban 2011b). Herbert Daniel Kleber was born January 19, 1934, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His family’s father’s side was from Vilnius, Lithuania, and the Mother’s side was from Germany. Both families came to the United State during the first decade of the 20th century. -

Switching from Clonidine Immediate-Release to Guanfacine Extended-Release

/ DE L’ACADÉMIE CANADIENNE DE PSYCHIATRIE DE L’ENFANT ET DE L’ADOLESCENT PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY Switching from Clonidine Immediate-Release to Guanfacine Extended-Release Dean Elbe PharmD, BCPP1,2,3 s a clinical pharmacy specialist in child and adolescent (Canada) Ltd, 2012b). Clonidine has been used off-label Amental health, I am frequently asked how to switch in children for many years for treatment of insomnia, patients from clonidine immediate-release (IR) to guanfa- ADHD, and disruptive behaviour disorders (Hunt, Capper cine extended-release (XR). This therapeutic switch may be & O’Connell, 1990; Rubinstein; Jaselskis, Cook, Fletcher required when poor adherence to a clonidine IR regimen & Leventhal, 1992; Silver & Licamele, 1994; Palumbo et (typically requiring 3–4 doses daily) is identified, when al., 2008; Efron, Lycett & Sciberras, 2014). A clonidine XR clonidine dose-optimization is limited by sedation, brady- formulation is not available in Canada, but is available in cardia or hypotension, or when coverage situations change. the United States for treatment of ADHD (Concordia Phar- The latter may occur if, for example, new eligibility for a maceuticals, Inc. 2015). government program or a third party-payer occurs. Weight-based dosing guidelines exist for clonidine IR Guanfacine XR, a selective alpha2A agonist, was first mar- (0.003–0.008 mg/kg/day) and guanfacine XR (0.05–0.08 keted in Canada in late 2013 for the treatment of attention mg/kg/day) (Shire Pharma Canada ULC, 2019; Elbe et deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and ado- al., 2018). Based on these guidelines and other literature, lescents (Shire Pharma Canada ULC, 2019). -

Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction

Advances in Opioid Antagonist Treatment for Opioid Addiction a, a b Walter Ling, MD *, Larissa Mooney, MD , Li-Tzy Wu, ScD KEYWORDS • Addiction treatment • Depot naltrexone • Opioid dependence • Relapse KEY POINTS • The major problem with oral naltrexone is noncompliance. Administration of naltrexone as an intramuscular injection may be less onerous and improve compliance because it occurs only once a month (ie, extended-release depot naltrexone). • To initiate treatment with extended-release depot naltrexone, steps should be taken to ensure that the patient is sufficiently free from physical dependence on opioids (eg, detoxification). • Research on naltrexone in combination with other medications suggests many opportu- nities for studying mixed receptor activities in the treatment of opioid and other drug addictions. PERSPECTIVE ON OPIOID ANTAGONIST TREATMENT FOR ADDICTION Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist derived from the analgesic oxymorphone, was synthesized as EN-1639A by Blumberg and colleagues in 1967. Four years later, in 1971, naltrexone was selected for high-priority development as a treatment for opioid addiction by the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, an office created by President Nixon and put under the leadership of Dr Jerome Jaffe. Extinction Model The rationale for the antagonist approach to treating opioid addiction had been advanced by Dr Abraham Wikler a decade earlier, based largely on the extinction model explored in animal behavioral studies. It was believed that by blocking the euphorogenic effects of opioids at the opioid receptors, opiate use would become Disclosures: Dr Ling has served as a consultant to Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals and to Alkermes, Inc. Dr Mooney and Dr Wu report no relationships with commercial companies with any interest in the article’s subject matters. -

Localisation of Visual Hallucinations

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 16 JULY 1977 147 of hypothermia; the duration of cardiac arrest; and the disturbances of sleep or consciousness.4 Hallucinations may be promptness and correctness of treatment. Peterson's pessi- evoked by sensory deprivation, but other factors are usually mistic report from California,8 in which all 15 near-drowned present; thus the "black-patch" delirium that may follow children who had fits, fixed dilated pupils, flaccidity, and loss cataract extraction in the elderly probably results from sensory Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.6080.147 on 16 July 1977. Downloaded from of pain sensation suffered severe anoxic encephalopathy, deprivation and mild senile brain changes and is more frequent may be explained by the high water temperatures there. In when hearing is also impaired.5 warm water the protective effect of hypothermia against brain Hallucinations may be due to focal lesions. Past experiences, damage would be missing. In contrast was the case described the quality of eidetic imagery, and psychodynamic "actors in Trondheim, Norway,9 in which a 5-year-old fell through influence the content of organic hallucinosis,6 and it would be ice in fresh water with an outside temperature of 10° below unwise to lean too heavily on the occurrence and nature of zero centigrade. He was in the water for 22 minutes and was hallucinosis in localising intracranial lesions. Visual hallucina- brought out apparently dead, with widely dilated pupils and tions are a relatively infrequent accompaniment oflesions ofthe bluish white skin. He was warmed up (the method was not calcarine cortex (Brodmann's area 17), which has few thalamo- described) and-despite the risks noted above-was given cortical connections; yet they may occur as a false-localising external cardiac massage without suffering ventricular symptom of frontal or subtentorial lesions. -

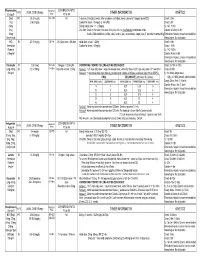

Medication Conversion Chart

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

Subliminal Afterimages Via Ocular Delayed Luminescence: Transsaccade Stability of the Visual Perception and Color Illusion

ACTIVITAS NERVOSA SUPERIOR Activitas Nervosa Superior 2012, 54, No. 1-2 REVIEW ARTICLE SUBLIMINAL AFTERIMAGES VIA OCULAR DELAYED LUMINESCENCE: TRANSSACCADE STABILITY OF THE VISUAL PERCEPTION AND COLOR ILLUSION István Bókkon1,2 & Ram L.P. Vimal2 1Doctoral School of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary 2Vision Research Institute, Lowell, MA, USA Abstract Here, we suggest the existence and possible roles of evanescent nonconscious afterimages in visual saccades and color illusions during normal vision. These suggested functions of subliminal afterimages are based on our previous papers (i) (Bókkon, Vimal et al. 2011, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B) related to visible light induced ocular delayed bioluminescence as a possible origin of negative afterimage and (ii) Wang, Bókkon et al. (Brain Res. 2011)’s experiments that proved the existence of spontaneous and visible light induced delayed ultraweak photon emission from in vitro freshly isolated rat’s whole eye, lens, vitreous humor and retina. We also argue about the existence of rich detailed, subliminal visual short-term memory across saccades in early retinotopic areas. We conclude that if we want to understand the complex visual processes, mere electrical processes are hardly enough for explanations; for that we have to consider the natural photobiophysical processes as elaborated in this article. Key words: Saccades Nonconscious afterimages Ocular delayed bioluminescence Color illusion 1. INTRODUCTION Previously, we presented a common photobiophysical basis for various visual related phenomena such as discrete retinal noise, retinal phosphenes, as well as negative afterimages. These new concepts have been supported by experiments (Wang, Bókkon et al., 2011). They performed the first experimental proof of spontaneous ultraweak biophoton emission and visible light induced delayed ultraweak photon emission from in vitro freshly isolated rat’s whole eye, lens, vitreous humor, and retina. -

Lega Italiana Per La Lotta Contro La Malattia Di Parkinson Le Sindromi Extrapiramidali E Le Demenze

LIMPE lega italiana per la lotta contro la malattia di parkinson le sindromi extrapiramidali e le demenze Web site: http://www.parkinson-limpe.it/ XXIX National Congress Lecce 23–25 October 2002 Parkinson Parkinsonism Dementia: from Biotechnology to Medical Management SELECTED SHORT PAPERS Scientific Committee Bruno Bergamasco, Giovanni U. Corsini, Mario Manfredi, Stefano Ruggieri, Pierfranco Spano Secretariat LIMPE Viale dell’Università 30, 00185 Roma Tel. and Fax: +39-06-4455618 E-mail: [email protected] Neurol Sci (2003) 24:149–150 DOI 10.1007/s10072-003-0103-5 123I-Ioflupane/SPECT binding to to the dopamine transporter (DAT) may be better suited and provide more-accurate estimation of degeneration. Several striatal dopamine transporter (DAT) tracers that bind to DAT and utilize SPECT are available; uptake in patients with Parkinson’s they are all cocaine derivatives. The most widely used are disease, multiple system atrophy, and [123I]β-CIT and 123I-Ioflupane ([123I]FP-CIT) [3, 4]. The main advantage of 123I-Ioflupane is that a steady state allow- progressive supranuclear palsy ing SPECT imaging is reached 3 h after a single bolus injec- 1 2 1 tion of the radioligand, compared with the 18–24 h required A. Antonini (౧) • R. Benti • R. De Notaris 1 1 1 for [123I]β-CIT. Therefore DAT imaging with 123I-Ioflupane S. Tesei • A. Zecchinelli • G. Sacilotto 1 1 1 1 can be completed the same day. N. Meucci • M. Canesi • C. Mariani • G. Pezzoli 123 P. Gerundini2 Several studies have demonstrated the usefulness of I- 1 Centro per la malattia di Parkinson, Dipartimento di Ioflupane SPECT imaging in the diagnosis of parkinsonism. -

Visual Perception in Migraine: a Narrative Review

vision Review Visual Perception in Migraine: A Narrative Review Nouchine Hadjikhani 1,2,* and Maurice Vincent 3 1 Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02129, USA 2 Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 41119 Gothenburg, Sweden 3 Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN 46285, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-617-724-5625 Abstract: Migraine, the most frequent neurological ailment, affects visual processing during and between attacks. Most visual disturbances associated with migraine can be explained by increased neural hyperexcitability, as suggested by clinical, physiological and neuroimaging evidence. Here, we review how simple (e.g., patterns, color) visual functions can be affected in patients with migraine, describe the different complex manifestations of the so-called Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, and discuss how visual stimuli can trigger migraine attacks. We also reinforce the importance of a thorough, proactive examination of visual function in people with migraine. Keywords: migraine aura; vision; Alice in Wonderland Syndrome 1. Introduction Vision consumes a substantial portion of brain processing in humans. Migraine, the most frequent neurological ailment, affects vision more than any other cerebral function, both during and between attacks. Visual experiences in patients with migraine vary vastly in nature, extent and intensity, suggesting that migraine affects the central nervous system (CNS) anatomically and functionally in many different ways, thereby disrupting Citation: Hadjikhani, N.; Vincent, M. several components of visual processing. Migraine visual symptoms are simple (positive or Visual Perception in Migraine: A Narrative Review. Vision 2021, 5, 20. negative), or complex, which involve larger and more elaborate vision disturbances, such https://doi.org/10.3390/vision5020020 as the perception of fortification spectra and other illusions [1]. -

Psychoactive Substances and Transpersonal States

TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOLOGY RESEARCH REVIEW: PSYCHOACTIVE SUBSTANCES AND TRANSPERSONAL STATES David Lukoff San Francisco, California Robert Zanger Los Angeles, California Francis Lu San Francisco, California This "Research Review" covers recent trends in researching psychoactive substances and trans personal states of conscious ness during the past ten years. In keeping with the stated goals of this section of the Journal to promote research in transpersonal psychology, the focus is on the methods and trends designs which are being employed in investigations rather than during the findings on this topic. However, some recently published the books and monographs provide good summaries of the recent last findings relevant to understanding psychoactive substances ten (Cohen & Krippner, 1985b; Dobkin de Rios, 1984;Dobkin de years Rios & Winkelman, 1989b; Ratsch, 1990; Reidlinger, 1990). Because researching psychoactive substances is most broadly a cross-disciplinary venture, only a small portion of the research reviewed below was conducted by persons who consider The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Bruce Flath, head librarian at the California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco in conducting the computer bibliographic searches used in preparation of this article. The authors also wish to thank Marlene Dobkin de Rios, Stanley Krippner, Christel Lukoff, Dennis McKenna, Terence McKenna, Ralph Metzner, Donald Rothberg and Ilene Serlin for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. Copyright © 1990 Transpersonal Institute The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 1990, Vol. 22, No.2 107 themselves transpersonal psychologists. As Vaughan (1984) has noted, "The transpersonal perspective is a meta-perspec tive, an attempt to learn from all different disciplines . emerging from the needed integration of ancient wisdom and modern science. -

Federal Air Surgeon's

Federal Air Surgeon’s Medical Bulletin Aviation Safety Through Aerospace Medicine 02-4 For FAA Aviation Medical Examiners, Office of Aerospace Medicine U.S. Department of Transportation Winter 2002 Personnel, Flight Standards Inspectors, and Other Aviation Professionals. Federal Aviation Administration Best Practices This article launches Best Practices, a new series of HEADS UP profiles highlighting the shared wisdom of the most A Dean Among Doctors senior of our senior aviation medical examiners. 2 Editorial: Research By Mark Grady Written by one of Dr. Moore’s pilot medical and Aviation Safety General Aviation News certification applicants, this article appeared in the November 22, 2002, issue of General Avia- 3 Certification Issues OCTOR W. DONALD MOORE of tion News. —Ed. and Answers Coats, N.C., knows a lot of pilots 6 Bariatric D— many quite intimately. After Surgery: all, as an Federal Administra- morning just to give medical exams for pilots in the area. How Long tion Aviation Administration- approved medical examiner, He estimates he’s given more to Wait? he’s poked and prodded quite than 12,000 flight physicals a few of them during his more over the past 41 years. 7 Checklist for than 40 years of making sure “I’ve given an average of Pilot they meet the FAA’s physical 300 flight physicals a year since Physical requirements for flying. 1960,” he says, noting those He also knows what it’s like exams have been in addition to fly, because he flew for 40 to running a busy general 8 Palinopsia Case years. medical and obstetrics Report Moore began giving FAA Dr. -

Selective Knockdown of TASK3 Potassium Channel in Monoamine

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript Fullana et al - TASK3.docx 1 Research Article – Molecular Neurobiology 2 3 Selective Knockdown of TASK3 Potassium Channel in Monoamine 4 Neurons: A New Therapeutic Approach for Depression 5 M Neus Fullana1,2,3*, Albert Ferrés-Coy1,2,3*, Jorge E Ortega3,4, Esther Ruiz-Bronchal1,2,3, Verónica 6 Paz1,2,3, J Javier Meana3,4, Francesc Artigas1,2,3 and Analia Bortolozzi1,2,3 7 8 1Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain 9 2Department of Neurochemistry and Neuropharmacology, IIBB-CSIC (Consejo Superior de 10 Investigaciones Científicas), Barcelona, Spain. 11 3Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), ISCIII, Madrid, Spain. 12 4Department of Pharmacology, University of Basque Country UPV/EHU and BioCruces Health 13 Research Institute, Bizkaia, Spain 14 15 NF* and AF-C* contributed equally to this work. 16 For correspondence: Analia Bortolozzi, Department of Neurochemistry and Neuropharmacology 17 (IIBB-CSIC), Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi I Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Rosello 161, 18 Barcelona 08036, Spain. Tel: +34 93638313 Fax: +34 933638301 E-mail: 19 [email protected] 20 21 22 23 Running title: Intranasal delivery of conjugated TASK3-siRNA 24 25 26 1 Abstract 2 Current pharmacological treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD) are severely compromised 3 by both slow action and limited efficacy. RNAi strategies have been used to evoke antidepressant-like 4 effects faster than classical drugs. Using small interfering RNA (siRNA), we herein show that TASK3 5 potassium channel knockdown in monoamine neurons induces antidepressant-like responses in mice.