File System Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configuring UNIX-Specific Settings: Creating Symbolic Links : Snap

Configuring UNIX-specific settings: Creating symbolic links Snap Creator Framework NetApp September 23, 2021 This PDF was generated from https://docs.netapp.com/us-en/snap-creator- framework/installation/task_creating_symbolic_links_for_domino_plug_in_on_linux_and_solaris_hosts.ht ml on September 23, 2021. Always check docs.netapp.com for the latest. Table of Contents Configuring UNIX-specific settings: Creating symbolic links . 1 Creating symbolic links for the Domino plug-in on Linux and Solaris hosts. 1 Creating symbolic links for the Domino plug-in on AIX hosts. 2 Configuring UNIX-specific settings: Creating symbolic links If you are going to install the Snap Creator Agent on a UNIX operating system (AIX, Linux, and Solaris), for the IBM Domino plug-in to work properly, three symbolic links (symlinks) must be created to link to Domino’s shared object files. Installation procedures vary slightly depending on the operating system. Refer to the appropriate procedure for your operating system. Domino does not support the HP-UX operating system. Creating symbolic links for the Domino plug-in on Linux and Solaris hosts You need to perform this procedure if you want to create symbolic links for the Domino plug-in on Linux and Solaris hosts. You should not copy and paste commands directly from this document; errors (such as incorrectly transferred characters caused by line breaks and hard returns) might result. Copy and paste the commands into a text editor, verify the commands, and then enter them in the CLI console. The paths provided in the following steps refer to the 32-bit systems; 64-bit systems must create simlinks to /usr/lib64 instead of /usr/lib. -

Apple Software Design Guidelines

Apple Software Design Guidelines May 27, 2004 Java and all Java-based trademarks are Apple Computer, Inc. trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun © 2004 Apple Computer, Inc. Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other All rights reserved. countries. OpenGL is a trademark of Silicon Graphics, No part of this publication may be Inc. reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, PowerPC and and the PowerPC logo are mechanical, electronic, photocopying, trademarks of International Business recording, or otherwise, without prior Machines Corporation, used under license written permission of Apple Computer, Inc., therefrom. with the following exceptions: Any person Simultaneously published in the United is hereby authorized to store documentation States and Canada. on a single computer for personal use only Even though Apple has reviewed this manual, and to print copies of documentation for APPLE MAKES NO WARRANTY OR personal use provided that the REPRESENTATION, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, WITH RESPECT TO THIS MANUAL, documentation contains Apple's copyright ITS QUALITY, ACCURACY, notice. MERCHANTABILITY, OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. AS A RESULT, THIS The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple MANUAL IS SOLD ªAS IS,º AND YOU, THE PURCHASER, ARE ASSUMING THE ENTIRE Computer, Inc. RISK AS TO ITS QUALITY AND ACCURACY. Use of the ªkeyboardº Apple logo IN NO EVENT WILL APPLE BE LIABLE FOR DIRECT, INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, (Option-Shift-K) for commercial purposes OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES without the prior written consent of Apple RESULTING FROM ANY DEFECT OR may constitute trademark infringement and INACCURACY IN THIS MANUAL, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. -

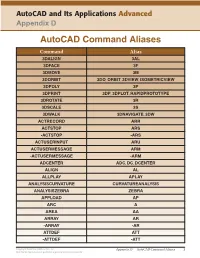

Autocad Command Aliases

AutoCAD and Its Applications Advanced Appendix D AutoCAD Command Aliases Command Alias 3DALIGN 3AL 3DFACE 3F 3DMOVE 3M 3DORBIT 3DO, ORBIT, 3DVIEW, ISOMETRICVIEW 3DPOLY 3P 3DPRINT 3DP, 3DPLOT, RAPIDPROTOTYPE 3DROTATE 3R 3DSCALE 3S 3DWALK 3DNAVIGATE, 3DW ACTRECORD ARR ACTSTOP ARS -ACTSTOP -ARS ACTUSERINPUT ARU ACTUSERMESSAGE ARM -ACTUSERMESSAGE -ARM ADCENTER ADC, DC, DCENTER ALIGN AL ALLPLAY APLAY ANALYSISCURVATURE CURVATUREANALYSIS ANALYSISZEBRA ZEBRA APPLOAD AP ARC A AREA AA ARRAY AR -ARRAY -AR ATTDEF ATT -ATTDEF -ATT Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 1 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias ATTEDIT ATE -ATTEDIT -ATE, ATTE ATTIPEDIT ATI BACTION AC BCLOSE BC BCPARAMETER CPARAM BEDIT BE BLOCK B -BLOCK -B BOUNDARY BO -BOUNDARY -BO BPARAMETER PARAM BREAK BR BSAVE BS BVSTATE BVS CAMERA CAM CHAMFER CHA CHANGE -CH CHECKSTANDARDS CHK CIRCLE C COLOR COL, COLOUR COMMANDLINE CLI CONSTRAINTBAR CBAR CONSTRAINTSETTINGS CSETTINGS COPY CO, CP CTABLESTYLE CT CVADD INSERTCONTROLPOINT CVHIDE POINTOFF CVREBUILD REBUILD CVREMOVE REMOVECONTROLPOINT CVSHOW POINTON Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. Appendix D — AutoCAD Command Aliases 2 May not be reproduced or posted to a publicly accessible website. Command Alias CYLINDER CYL DATAEXTRACTION DX DATALINK DL DATALINKUPDATE DLU DBCONNECT DBC, DATABASE, DATASOURCE DDGRIPS GR DELCONSTRAINT DELCON DIMALIGNED DAL, DIMALI DIMANGULAR DAN, DIMANG DIMARC DAR DIMBASELINE DBA, DIMBASE DIMCENTER DCE DIMCONSTRAINT DCON DIMCONTINUE DCO, DIMCONT DIMDIAMETER DDI, DIMDIA DIMDISASSOCIATE DDA DIMEDIT DED, DIMED DIMJOGGED DJO, JOG DIMJOGLINE DJL DIMLINEAR DIMLIN, DLI DIMORDINATE DOR, DIMORD DIMOVERRIDE DOV, DIMOVER DIMRADIUS DIMRAD, DRA DIMREASSOCIATE DRE DIMSTYLE D, DIMSTY, DST DIMTEDIT DIMTED DIST DI, LENGTH DIVIDE DIV DONUT DO DRAWINGRECOVERY DRM DRAWORDER DR Copyright Goodheart-Willcox Co., Inc. -

Power Mac G4 (Digital Audio): Setting up (Manual)

Setting Up Your Power Mac G4 Includes setup and expansion information for Power Mac G4 and Macintosh Server G4 computers K Apple Computer, Inc. © 2001 Apple Computer, Inc. All rights reserved. Under the copyright laws, this manual may not be copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Apple. The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo (Option-Shift-K) for commercial purposes without the prior written consent of Apple may constitute trademark infringement and unfair competition in violation of federal and state laws. Every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this manual is accurate. Apple is not responsible for printing or clerical errors. Apple Computer, Inc. 1 Infinite Loop Cupertino, CA 95014-2084 408-996-1010 http://www.apple.com Apple, the Apple logo, AppleShare, AppleTalk, FireWire, the FireWire logo, Mac, Macintosh, the Mac logo, PlainTalk, Power Macintosh, QuickTime, and Sherlock are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. AirPort, the Apple Store, Finder, iMovie, and Power Mac are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. PowerPC and the PowerPC logo are trademarks of International Business Machines Corporation, used under license therefrom. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. “Dolby” and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Confidential Unpublished Works. © 1992–1997 Dolby Laboratories, Inc. All rights reserved. Other company and product names mentioned herein are trademarks of their respective companies. Mention of third-party products is for informational purposes only and constitutes neither an endorsement nor a recommendation. -

The Microsoft Compound Document File Format"

OpenOffice.org's Documentation of the Microsoft Compound Document File Format Author Daniel Rentz ✉ mailto:[email protected] http://sc.openoffice.org License Public Documentation License Contributors Other sources Hyperlinks to Wikipedia ( http://www.wikipedia.org) for various extended information Mailing list ✉ mailto:[email protected] Subscription ✉ mailto:[email protected] Download PDF http://sc.openoffice.org/compdocfileformat.pdf XML http://sc.openoffice.org/compdocfileformat.odt Project started 2004-Aug-30 Last change 2007-Aug-07 Revision 1.5 Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 1.1 License Notices 3 1.2 Abstract 3 1.3 Used Terms, Symbols, and Formatting 4 2 Storages and Streams ........................................................................................... 5 3 Sectors and Sector Chains ................................................................................... 6 3.1 Sectors and Sector Identifiers 6 3.2 Sector Chains and SecID Chains 7 4 Compound Document Header ............................................................................. 8 4.1 Compound Document Header Contents 8 4.2 Byte Order 9 4.3 Sector File Offsets 9 5 Sector Allocation ............................................................................................... 10 5.1 Master Sector Allocation Table 10 5.2 Sector Allocation Table 11 6 Short-Streams ................................................................................................... -

Mac OS 8 Update

K Service Source Mac OS 8 Update Known problems, Internet Access, and Installation Mac OS 8 Update Document Contents - 1 Document Contents • Introduction • About Mac OS 8 • About Internet Access What To Do First Additional Software Auto-Dial and Auto-Disconnect Settings TCP/IP Connection Options and Internet Access Length of Configuration Names Modem Scripts & Password Length Proxies and Other Internet Config Settings Web Browser Issues Troubleshooting • About Mac OS Runtime for Java Version 1.0.2 • About Mac OS Personal Web Sharing • Installing Mac OS 8 • Upgrading Workgroup Server 9650 & 7350 Software Mac OS 8 Update Introduction - 2 Introduction Mac OS 8 is the most significant update to the Macintosh operating system since 1984. The updated system gives users PowerPC-native multitasking, an efficient desktop with new pop-up windows and spring-loaded folders, and a fully integrated suite of Internet services. This document provides information about Mac OS 8 that supplements the information in the Mac OS installation manual. For a detailed description of Mac OS 8, useful tips for using the system, troubleshooting, late-breaking news, and links for online technical support, visit the Mac OS Info Center at http://ip.apple.com/infocenter. Or browse the Mac OS 8 topic in the Apple Technical Library at http:// tilsp1.info.apple.com. Mac OS 8 Update About Mac OS 8 - 3 About Mac OS 8 Read this section for information about known problems with the Mac OS 8 update and possible solutions. Known Problems and Compatibility Issues Apple Language Kits and Mac OS 8 Apple's Language Kits require an updater for full functionality with this version of the Mac OS. -

Mac Keyboard Shortcuts Cut, Copy, Paste, and Other Common Shortcuts

Mac keyboard shortcuts By pressing a combination of keys, you can do things that normally need a mouse, trackpad, or other input device. To use a keyboard shortcut, hold down one or more modifier keys while pressing the last key of the shortcut. For example, to use the shortcut Command-C (copy), hold down Command, press C, then release both keys. Mac menus and keyboards often use symbols for certain keys, including the modifier keys: Command ⌘ Option ⌥ Caps Lock ⇪ Shift ⇧ Control ⌃ Fn If you're using a keyboard made for Windows PCs, use the Alt key instead of Option, and the Windows logo key instead of Command. Some Mac keyboards and shortcuts use special keys in the top row, which include icons for volume, display brightness, and other functions. Press the icon key to perform that function, or combine it with the Fn key to use it as an F1, F2, F3, or other standard function key. To learn more shortcuts, check the menus of the app you're using. Every app can have its own shortcuts, and shortcuts that work in one app may not work in another. Cut, copy, paste, and other common shortcuts Shortcut Description Command-X Cut: Remove the selected item and copy it to the Clipboard. Command-C Copy the selected item to the Clipboard. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-V Paste the contents of the Clipboard into the current document or app. This also works for files in the Finder. Command-Z Undo the previous command. You can then press Command-Shift-Z to Redo, reversing the undo command. -

Mac OS X Server Administrator's Guide

034-9285.S4AdminPDF 6/27/02 2:07 PM Page 1 Mac OS X Server Administrator’s Guide K Apple Computer, Inc. © 2002 Apple Computer, Inc. All rights reserved. Under the copyright laws, this publication may not be copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Apple. The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo (Option-Shift-K) for commercial purposes without the prior written consent of Apple may constitute trademark infringement and unfair competition in violation of federal and state laws. Apple, the Apple logo, AppleScript, AppleShare, AppleTalk, ColorSync, FireWire, Keychain, Mac, Macintosh, Power Macintosh, QuickTime, Sherlock, and WebObjects are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. AirPort, Extensions Manager, Finder, iMac, and Power Mac are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Adobe and PostScript are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Java and all Java-based trademarks and logos are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Netscape Navigator is a trademark of Netscape Communications Corporation. RealAudio is a trademark of Progressive Networks, Inc. © 1995–2001 The Apache Group. All rights reserved. UNIX is a registered trademark in the United States and other countries, licensed exclusively through X/Open Company, Ltd. 062-9285/7-26-02 LL9285.Book Page 3 Tuesday, June 25, 2002 3:59 PM Contents Preface How to Use This Guide 39 What’s Included -

Alias Manager 4

CHAPTER 4 Alias Manager 4 This chapter describes how your application can use the Alias Manager to establish and resolve alias records, which are data structures that describe file system objects (that is, files, directories, and volumes). You create an alias record to take a “fingerprint” of a file system object, usually a file, that you might need to locate again later. You can store the alias record, instead of a file system specification, and then let the Alias Manager find the file again when it’s needed. The Alias Manager contains algorithms for locating files that have been moved, renamed, copied, or restored from backup. Note The Alias Manager lets you manage alias records. It does not directly manipulate Finder aliases, which the user creates and manages through the Finder. The chapter “Finder Interface” in Inside Macintosh: Macintosh Toolbox Essentials describes Finder aliases and ways to accommodate them in your application. ◆ The Alias Manager is available only in system software version 7.0 or later. Use the Gestalt function, described in the chapter “Gestalt Manager” of Inside Macintosh: Operating System Utilities, to determine whether the Alias Manager is present. Read this chapter if you want your application to create and resolve alias records. You might store an alias record, for example, to identify a customized dictionary from within a word-processing document. When the user runs a spelling checker on the document, your application can ask the Alias Manager to resolve the record to find the correct dictionary. 4 To use this chapter, you should be familiar with the File Manager’s conventions for Alias Manager identifying files, directories, and volumes, as described in the chapter “Introduction to File Management” in this book. -

Integrated Voice Evacuation System Vx-3000 Series

SETTING SOFTWARE INSTRUCTIONS For Authorized Advanced End User INTEGRATED VOICE EVACUATION SYSTEM VX-3000 SERIES Tip In this manual, the VX-3004F/3008F/3016F Voice Evacuation Frames are collectively referred to as "VX-3000F." Thank you for purchasing TOA’s Integrated Voice Evacuation System. Please carefully follow the instructions in this manual to ensure long, trouble-free use of your equipment. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SOFTWARE OUTLINE ................................................................................... 3 2. NOTES ON PERFORMING SETTINGS .............................................. 3 2.1. System Requirements .......................................................................................... 3 2.2. Notes .................................................................................................................... 3 3. SOFTWARE SETUP ........................................................................................ 4 3.1. Setting Software Installation ................................................................................. 4 3.2. Uninstallation ....................................................................................................... 6 4. STARTING THE VX-3000 SETTING SOFTWARE ....................... 7 5. SETTING ITEMS ................................................................................................ 8 5.1. Setting Item Button Configuration ........................................................................ 8 5.2. Menu Bar ............................................................................................................. -

Where Do You Want to Go Today? Escalating

Where Do You Want to Go Today? ∗ Escalating Privileges by Pathname Manipulation Suresh Chari Shai Halevi Wietse Venema IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, Hawthorne, New York, USA Abstract 1. Introduction We analyze filename-based privilege escalation attacks, In this work we take another look at the problem of where an attacker creates filesystem links, thereby “trick- privilege escalation via manipulation of filesystem names. ing” a victim program into opening unintended files. Historically, attention has focused on attacks against priv- We develop primitives for a POSIX environment, provid- ileged processes that open files in directories that are ing assurance that files in “safe directories” (such as writable by an attacker. One classical example is email /etc/passwd) cannot be opened by looking up a file by delivery in the UNIX environment (e.g., [9]). Here, an “unsafe pathname” (such as a pathname that resolves the mail-delivery directory (e.g., /var/mail) is often through a symbolic link in a world-writable directory). In group or world writable. An adversarial user may use today's UNIX systems, solutions to this problem are typ- its write permission to create a hard link or symlink at ically built into (some) applications and use application- /var/mail/root that resolves to /etc/passwd. A specific knowledge about (un)safety of certain directories. simple-minded mail-delivery program that appends mail to In contrast, we seek solutions that can be implemented in the file /var/mail/root can have disastrous implica- the filesystem itself (or a library on top of it), thus providing tions for system security. -

Tinkertool System 7 Reference Manual Ii

Documentation 0642-1075/2 TinkerTool System 7 Reference Manual ii Version 7.5, August 24, 2021. US-English edition. MBS Documentation 0642-1075/2 © Copyright 2003 – 2021 by Marcel Bresink Software-Systeme Marcel Bresink Software-Systeme Ringstr. 21 56630 Kretz Germany All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be redistributed, translated in other languages, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. This publication may contain examples of data used in daily business operations. To illustrate them as completely as possible, the examples include the names of individuals, companies, brands, and products. All of these names are fictitious and any similarity to the names and addresses used by an actual business enterprise is entirely coincidental. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in new editions of the publication. The publisher may make improvements and/or changes in the product(s) and/or the program(s) described in this publication at any time without notice. Make sure that you are using the correct edition of the publication for the level of the product. The version number can be found at the top of this page. Apple, macOS, iCloud, and FireWire are registered trademarks of Apple Inc. Intel is a registered trademark of Intel Corporation. UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open Group. Broadcom is a registered trademark of Broadcom, Inc. Amazon Web Services is a registered trademark of Amazon.com, Inc.