The Role of Technical and Vocational Education and Training TUNISIA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C a Se Stud Y

This project is funded by the European Union November 2020 Culture in ruins The illegal trade in cultural property Case study: Algeria and Tunisia Julia Stanyard and Rim Dhaouadi Summary This case study forms part of a set of publications on the illegal trade in cultural property across North and West Africa, made up of a research paper and three case studies (on Mali, Nigeria and North Africa). This study is focused on Algeria and Tunisia, which share the same forms of material culture but very different antiquity markets. Attention is given to the development of online markets which have been identified as a key threat to this region’s heritage. Key findings • The large-scale extraction of cultural objects in both countries has its roots in the period of French colonial rule. • During the civil war in Algeria in the 1990s, trafficking in cultural heritage was allegedly linked to insurgent anti-government groups among others. • In Tunisia, the presidential family and the political elite reportedly dominated the country’s trade in archaeological objects and controlled the illegal markets. • The modern-day trade in North African cultural property is an interlinked regional criminal economy in which objects are smuggled between Tunisia and Algeria as well as internationally. • State officials and representatives of cultural institutions are implicated in the Algerian and Tunisian antiquities markets in a range of different capacities, both as passive facilitators and active participants. • There is evidence that some architects and real estate entrepreneurs are connected to CASE STUDY CASE trafficking networks. Introduction The region is a palimpsest of ancient material,7 much of which remains unexplored and unexcavated by Cultural heritage in North Africa has come under fire archaeologists. -

Morpho-Phenological Diversity Among Natural Populations of Medicago Polymorpha of Different Tunisian Ecological Areas

Vol. 15(25), pp. 1330-1338, 22 June, 2016 DOI: 10.5897/AJB2015.14950 Article Number: A52532059051 ISSN 1684-5315 African Journal of Biotechnology Copyright © 2016 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB Full Length Research Paper Morpho-phenological diversity among natural populations of Medicago polymorpha of different Tunisian ecological areas Mounawer Badri*, Najah Ben Cheikh, Asma Mahjoub and Chedly Abdelly Laboratory of Extremophile Plants, Centre of Biotechnology of Borj Cedria, B.P. 901, Hammam-Lif 2050, Tunisia. Received 27 August, 2015; Accepted 13 January, 2016 Medicago polymorpha is a herbaceous legume that can be a useful pasture plant, in particular, in regions with a Mediterranean climate. The genetic variation in 120 lines of M. polymorpha sampled from five regions in Tunisia was characterized on the basis of 16 morpho-phenological characters. Results from analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that differences among populations and lines existed for all traits, with population explaining the greatest variation for measured traits. The populations of Enfidha and Soliman were the earliest flowering, while those of El Kef, Bulla Regia and Mateur were the latest. El Kef and Mateur exhibited the highest aerial dry weight while the lowest value was found for Soliman. Moderate to lower levels of heritability (H²) were registered for investigated traits. There was no significant association between pairwise population differentiation (QST) and geographical distances. Studied lines were clustered into three groups with 59 for the first group, 34 for the second group, and 27 lines for the third group. The lines of the first two groups showed the largest length of stems while those of the second group had the highest number of leaves. -

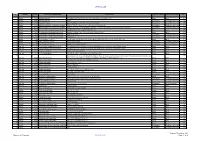

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Revision of the Genus Sternocoelis Lewis, 1888 (Coleoptera: Histeri- Dae), with a Proposed Phylogeny

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/ Revue suisse de zoologie. Genève,Kundig [etc.] http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/8981 t.102:fasc.1-2 (1995): http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/128645 Article/Chapter Title: Revision of the genus Sternocoelis Author(s): Yelamos Subject(s): Histeridae Page(s): Text, Page 114, Page 115, Page 116, Page 117, Page 118, Page 119, Page 120, Page 121, Page 122, Page 123, Page 124, Page 125, Page 126, Page 127, Page 128, Page 129, Page 130, Page 131, Page 132, Page 133, Page 134, Page 135, Page 136, Page 137, Page 138, Page 139, Page 140, Page 141, Page 142, Page 143, Page 144, Page 145, Page 146, Page 147, Page 148, Page 149, Page 150, Page 151, Page 152, Page 153, Page 154, Page 155, Page 156, Page 157, Page 158, Page 159, Page 160, Page 161, Page 162, Page 163, Page 164, Page 165, Page 166, Page 167, Page 168, Page 169, Page 170, Page 171, Page 172, Page 173, Page 174 Contributed by: Smithsonian Libraries Sponsored by: Biodiversity Heritage Library Generated 5 March 2017 7:03 PM http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/pdf4/062543700128645 This page intentionally left blank. The following text is generated from uncorrected OCR. [Begin Page: Text] Revue suisse de Zoologie, 102 (1) : 113-174; mars 1995 Revision of the genus Sternocoelis Lewis, 1888 (Coleoptera: Histeridae), with a proposed phylogeny Tomàs YÉLAMOS Museu de Zoologia Apartat de Correus 593 08080 Barcelona (Spain). Revision of the genus Sternocoelis Lewis, 1888 (Coleoptera: Histeri- dae), with a proposed phylogeny. - Twenty six species of Sternocoelis Lewis are currently recognized and all occur in the Mediterranean region. -

We Thank You Much for Your Interest Allow Us Please

Dear Sir; We thank you much for your interest to our packed Extra Virgin O live Oil. Allow us please this historical overview, it’s reminds us Tunisian olive oil origin and therefore Tunisian civilization … it shows how Tunisian olive oil is glorious. For thousands of years, olive oil has been prominent in all great civilizations that have prospered in Tunisia. Olive tree was cultivated by Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans and Arabs, in a tradition that has been passed down from father to son ever since. Olive cultivation in Tunisia dates back to the 8th century BC, even before the founding of Carthage by Queen Dido. Phoenicians were the first introducing this crop to North Africa and especially to Tunisia. In Carthaginian period, olive cultivation started to spread on account of several advantages granted to olive-growers. Romans continued the expansion of olive -growing stepped-up irrigation, olive oil extraction technique. as evidenced by Excavations at Sufeitula (present-day Sbeitla) and Thysdrus (El Jem, territorially and administratively attached to Mahdia Governorate from where we introduce you «Zeten Bottled Extra Virgin Olive Oil») We hope you allow us introducing fo r you Bottled Tunisian Extra Virgin Olive Oil witch is obtained naturally at First Cold Extraction and witch labeled ZETEN. Brand: ZETEN Producer: SOCHO ZETEN S.A. Origin: Tunisia, Al -Mahdia Town Quality: Extra Virgin Olive Oil according to IOC standards with acidity ≤0.45% Taste & Smell: Sweet Spice Nicely, Fruity Flavor, Absolutely Perfect « Audience -

Perspektiven Der Spolienforschung 2. Zentren Und Konjunkturen Der

Perspektiven der Spolienforschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD antiker Bauten, Bauteile und Skulpturen ist ein weitverbreite- tes Phänomen der Nachantike. Rom und der Maghreb liefern zahlreiche und vielfältige Beispiele für diese An- eignung materieller Hinterlassenscha en der Antike. Während sich die beiden Regionen seit dem Ausgang der Antike politisch und kulturell sehr unterschiedlich entwickeln, zeigen sie in der praktischen Umsetzung der Wiederverwendung, die zwischenzeitlich quasi- indus trielle Ausmaße annimmt, strukturell ähnliche orga nisatorische, logistische und rechtlich-lenkende Praktiken. An beiden Schauplätzen kann die Antike alternativ als eigene oder fremde Vergangenheit kon- struiert und die Praxis der Wiederverwendung utili- taristischen oder ostentativen Charakter besitzen. 40 · 40 Perspektiven der Spolien- forschung Stefan Altekamp Carmen Marcks-Jacobs Peter Seiler Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Abbildung Umschlag: Straßenkreuzung in Tripolis, Photo: Stefan Altekamp Typographisches Konzept und Einbandgestaltung: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN ---- URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:- First published Published under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC . DE. For the terms of use of the illustrations, please see the reference lists. www.edition-topoi.org INHALT , -, Einleitung — 7 Commerce de Marbre et Remploi dans les Monuments de L’Ifriqiya Médiévale — 15 Reuse and Redistribution of Latin Inscriptions on Stone in Post-Roman North-Africa — 43 Pulcherrima Spolia in the Architecture and Urban Space at Tripoli — 67 Adding a Layer. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

El Kef, Tunisia)

Marine Micropaleontology 55 (2005) 1–17 www.elsevier.com/locate/marmicro Paleocene sea-level and productivity changes at the southern Tethyan margin (El Kef, Tunisia) Elisa Guastia,T, Tanja J. Kouwenhovenb, Henk Brinkhuisc, Robert P. Speijerd aDepartment of Geosciences (FB 5), Bremen University, P.O. Box 330440, 28334 Bremen, Germany bDepartment of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands cLaboratory of Palaeobotany and Palynology, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands dDepartment of Geography and Geology, K.U. Leuven, Redingenstraat 16, 3000 Leuven, Belgium Received 24 August 2004; received in revised form 22 December 2004; accepted 3 January 2005 Abstract Integrated analysis of quantitative distribution patterns of organic-walled dinoflagellate cysts (dinocysts) and benthic foraminifera from the Paleocene El Kef section (NW Tunisia) allows the reconstruction of sea-level and productivity fluctuations. Our records indicate that the environment evolved from an initially oligotrophic, open marine, outer neritic to upper bathyal setting towards a more eutrophic inner neritic setting, influenced by coastal upwelling by the end of the Paleocene. An overall second order change in paleodepth is reflected by both microfossil groups. From the base of planktic foraminifera Zone P4 onwards, the main phase of shallowing is evidenced by an increase of inner neritic dinocysts of the Areoligera group, disappearance of deeper-water benthic foraminifera and increasing dominance of shallow-marine taxa (several buliminids, Haplophragmoides spp., Trochammina spp.). The total magnitude of this shallowing is obscured by interaction with a signal of eutrophication, but estimated to be around 150 m (from ~200 to ~50 m). -

Synopsis of the Orthomus Rubicundus Group with Description of Two New Species and a New Subspecies from Morocco and Algeria (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Pterostichini)

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 37/1 875-898 25.7.2005 Synopsis of the Orthomus rubicundus group with description of two new species and a new subspecies from Morocco and Algeria (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Pterostichini) D.W. WRASE & C. JEANNE Abstract: Orthomus starkei spec, nova (type locality: Morocco, Taza Province: ca. 5 km S Sebt-des-Beni-Frassen, 30 km NW Taza, 34.20N/04.22W), Orthomus tazekensis rifensis subspec. nova (type locality: Morocco, Chefchaouen Province: Rif Mts., Bab-Besen, ca. 15 km NW Ketama, ca 1600 m) and Orthomus achilles spec, nova (type locality: Alge- ria, Bejai'a Wilaya: Aokas, ca. 20 km SE Bejai'a) are described. Comparisons are made to species of the O. rubicundus group from northern Africa and southernmost Andalucia. A key for distinguishing the species is given, the main characters are mentioned and the localities of the examined material are listed. Illustrations of the habitus and the median lobes of the spe- cies dealt with here and a table with variation of values of some ratios are presented. Key words: Coleoptera, Carabidae, Pterostichini, Orthomus, new species, new subspecies, key, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, southern Spain. Introduction The genus Orthomus CHAUDOIR 1838 contains about 20 species being rather similar in structure and shape, occurring in the Mediterranea from the Canaries in the west to the Near East. All species are micropterous with elytra mostly fused at the suture, some of them form more or less well-differentiated subspecies. Among them there is a group of species from northern Africa with one species occuring also in southernmost Andalucia, which are characterized by some morphological features (eyes very flat, with longer tempora and with metepistema as long as wide or only a little longer than wide and only very weakly narrowed toward behind), contrary to the species group which members have eyes very convex with shorter tempora and metepistema, which are either distinctly longer than wide and strongly narrowed posteriorly or also short. -

Situation Update Maps

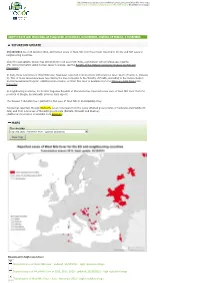

http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/west_nile_fever/West-Nile-fever-maps ECDC Portal > English > Health Topics > West Nile fever > West Nile fever maps NEXT UPDATE AND MAPS WILL BE PUBLISHED ON MONDAY, 5 NOVEMBER, INSTEAD OF FRIDAY, 3 NOVEMBER. SITUATION UPDATE 25/10/2012 As of 25 October 2012, 228 human cases of West Nile fever have been reported in the EU and 547 cases in neighbouring countries. Since the last update, Greece has detected one new case from Pella, a prefecture with previous case reports. (For more information about human cases in Greece, see the Bulletin of the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.) In Italy, three new cases of West Nile fever have been reported from provinces with previous case reports (Treviso 1, Venezia 3). Two of these cases have been reported by the Veneto Region to the Ministry of Health, according to the Veneto Region Special Surveillance Program. (Additional information on West Nile fever is available from the Ministero della Salute and Epicentro) In neighbouring countries, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has reported a new case of West Nile fever from the province of Skopje, an area with previous case reports. The Russian Federation has reported the first case of West Nile in Stavropolskiy Kray. Tunisia has reported, through EpiSouth, seven new cases from the newly affected governorates of Jendouba and Mahdia (El Jem) and from new areas of Monastir governorate (Bembla, Monastir and Shaline). (Additional information is available from EpiSouth) MAPS Choose map Reported -

Official Gazette of the Republic of Tunisia — 8 July 2008 N° 55 Page

Article 150 (second dash new) - The keeping of an 2006-2167 dated 10 August 2006, and decree n° 2007-1329 information register about the holders of the public dated 4 June 2007, and decree n° 2008-561 dated 4 March procurements on the base of follow up slips established 2008, after the performance of each procurement. The methods Having regard to the opinion of the Minister of Finance, relating to the information register and the follow up slips Having regard to the opinion of the Administrative are determined by order of the Prime Minister Court. Art. 3 - The provision of the decree herein shall be implemented immediately to the current procurements at Decrees the following: the time of its publication, except for articles 42 bis and 115 Article one – The holders of the public procurements of bis. The public purchaser establishes the annexes to the works who suffered from loss due to the abnormal increase current procurements with regard to the deadline of in the prices of the basic raw materials may get payment and restitution of caution according to the exceptionally the review of the contractual prices of the provisions of the decree herein. concerned procurements, according to the conditions and Art. 4 - The Prime Minister, the Minister and secretaries procedures stipulated in the decree herein. of the state, each in his respective capacity, shall implement Art. 2 - The exceptional review referred to in the the decree herein which shall be published in the Official previous article deals with the public procurements with Gazette of the Republic of Tunisia .