A View of American Orphanages Through a Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950

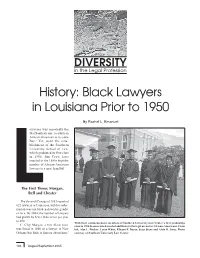

DIVERSITY in the Legal Profession History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950 By Rachel L. Emanuel ouisiana was reportedly the first Southern state to admit an African-American to its state Bar.1 Yet, until the esta- blishment of the Southern University School of Law, which graduated its first class in 1950, Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s kept the number of African-American lawyers to a mere handful. The First Three: Morgan, LBell and Chester The Seventh Census of 1853 reported 622 lawyers in Louisiana, but this infor- mation was not broken down by gender or race. By 1864, the number of lawyers had grown by fewer than seven per year to 698. With their commencement, members of Southern University Law Center’s first graduating C. Clay Morgan, a free black man, class in 1950 became much-needed additions to the legal arena for African-Americans. From was listed in 1860 as a lawyer in New left, Alex L. Pitcher, Leroy White, Ellyson F. Dyson, Jesse Stone and Alvin B. Jones. Photo Orleans but little is known about him.2 courtesy of Southern University Law Center. 104 August/September 2005 There were only four states reported to have admitted black lawyers to the bar prior to that time, none of them in the South. The states included Indiana (1860s), Maine (1844), Massachusetts (1845), New York (1848) and Ohio (1854). If, as is believed, Morgan was Louisiana’s first black lawyer,3 he would have been admitted to the Bar almost 10 years earlier than the average date for the other Southern states (Arkansas, 1866; Tennessee, 1868; Florida and Missis- sippi, 1869; Alabama, Georgia, Ken- tucky, South Carolina and Virginia, 1871; and Texas, 1873). -

Oregon Pythian News

Volume 24, Issue 2 December 2014 News for and About Oregon Pythians Oregon Pythian News Pythian Floats a Success Thanks to GC Randy & Gaston Lodge GASTON / HILLSBORO—Brother Knights of Gaston Lodge brought life to Grand Chancellor Randy Tipton’s idea that Oregon Pythians should promote our Order by having Pythian Floats in community parades around the state this year. The Knights built a great float which they took to Hillsboro for their 4th of July Parade. Members of both Gaston and Hillsboro Pythians and their families rode on the float and tossed candy to children along the way. Response from the crowd was very positive. The photo to the left depicts the float and Pythians from Hillsboro and Gaston at the Hillsboro 4th of July parade. PENDLETON—Damon Lodge planned and organized a float for the dress up parade to highlight the many activities we do to support the youth of our community. Grand Chancellor Randy Tipton came to Pendleton to be on our float and was joined by the following members: Jim Aldrich, Dale Freeman, Kone Hancock, Bill Peal, Ray Cable, Rob Inscore, Ben Anderson, Brian Bradley and Roman Olivera. We invited organizations who we have helped with steak feeds and donations to join with us on the float with signs thanking the lodge for the support. Represented were Pioneer Relief Nursery, the Softball State Champion and Youth Wrestling Team. Bill Peal provided the truck and Ray Cable gave us the use of his 30-foot trailer to make a great float. We were honored to have a 6-foot Knight in full combat armor, standing on the top of Bill’s truck—to command the attention of the crowd. -

Pythian International

Celebrating 157 Years of Pythianism The New Pythian International PUBLISHED BY THE SUPREME LODGE KNIGHTS OF PYTHIAS VOLUME VII No.18 __ ________ SPRING/SUMMER 2021 Grand Lodge Conventions 2021 What we know as of this writing Massachusetts May 20-21 Peabody SVC Brown Supreme Council Meeting June 5, 2021 Newark, New Jersey Tennessee June 4-6 Pigeon Forge SIG Stamm Texas June 11 Mineral Wells DSC Tim Hood From the Indiana July 15-17 Desk of Supreme Chancellor Lafayette SS Morris Joel D. Fierstien, KGS Pennsylvania August 21 Dunmore DSC Charles Swartz III True to Our Principles Supreme Lodge Convention As we struggle to overcome what the coronavirus August 26 - 31, 2021 pandemic has brought to our world, turn to our Newark, New Jersey history and principles, Friendship, Charity, and Ohio September 2-4 Benevolence and Community Service for Fairborn commitment and guidance. President Abraham Lincoln wished our founders well, seeking to end Iowa September 10-11 the bitter divisiveness of the 1861-1865 war to save Des Moines the union. This remains viable to the present with society quite polarized. Practicing FC & B and New Jersey September 12 Monroe Township promoting Community Service are important to keep in mind as we become more active. Health, Michigan September 16-18 safety concerns, and a vaccinated population are Lansing paramount as we go forward. Cont. on page 2 SUPREME LODGE OFFICERS Supreme Chancellor’s Message JOEL FIERSTIEN, SC Cont. from front page 54 Cobblestone Blvd. Monroe Twp., NJ 08831 Promoting the Order, recruiting, and meeting may 973-994-1069 be ambitious, but are vital to recovery and growth. -

Volume 107 Number 1

PYTHIAN INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 2006 Modern & Historic Halifax N.S. For more information visit the new SUPREME CONVENTION WEBSITE www.knightsofpythias.ca SUPREME LODGE SUPREME TEMPLE NOTE BOOK CHAT ROOM By By LINDA BRIDGES ALFRED A. SALTZMAN, KGS Supreme Secretary Supreme Secretary IT HAPPENED AGAIN! The crew in the Supreme Lodge NEW EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] office spends countless hours and a lot of energy trying to keep the lodge rosters and the PYTHIAN INTERNATIONAL mailing Dear Sisters list up-to-date. For some unknown reason, the printer used a previous list when mailing out the latest copy of the magazine, instead of the one we provided. As a consequence, there was We have started a new year and look forward to the a slight mix-up in the distribution and we are sorry for any Supreme convention in Halifax this August. Annual reports inconvenience this may have caused. Hopefully, this will not will be going out this month, and I need them back on time happen again. in order to get ready for the convention. Supreme We want to welcome two new Grand Secretaries into our Representatives need to look for my information letter to midst: Eugene Mattinson of the Maritimes Provinces and Al Sims them regarding committee appointments, credentials of Virginia. We wish them good luck in a very difficult role and we needed and general information. I will be including a copy stand ready to help them in any way possible. of the list of banquets and events in my letter. ALL events I want to personally thank all Pythians who offered their best and banquets will be sent to the Ticket Master Eugene wishes and prayers for my knee replacement surgery. -

From One Eagle Scout to Another

From One Eagle Scout to Another New Jersey Deputy Grand Chancellor Larry Kalb, (f right, himself an Eagle Scout, welcomed the newest k member of the select fraternity, Vincent Sherrier of J 1 New Jersey Brick Township. Kalb served as District Scout Executive, Boy Scouts of America in 1988, when Sherrier was a Tiger Cub Scout and Vincent’s mother, Marianne Sherrier was a Day Camp Counselor. Kalb was a Day Camp Administrator. '• Vincent is in the process of earning more merit ^ badges and showing increased Scouting spirit so he can earn additional Palm awards. i (See page 23) • FRATERNAL ORDER • FRATERNAL ORDER m PYTHIAN SISTERS KNIGHTS OF PYTHIAS \|jj > FALL o 2001 ° Issue #3 Ki axiiiAi New Jersey donates > $20,000 to Assist i '■ t Deborah Foundation ■4■Hi- i- New Jersey Grand Vice Chancellor Saul Rochman, left and Grand Chancellor Elliott Strout, right, pass on $20,000 contribution to Dr. Dorothy Bisberg, director, Children’s Hospital, Newark Beth Israel Medical Center. The presen tation included a brunch and reception. Pythians have a continuing commitment to contribute $500,000 to the center. (See page 23) IIEADQI ARTERS0FT1IEORDER HEADQUARTERS OF THE ORDER KNIGHTS OK PVTHIAS SUPREME TEMPLE PYTHIAN SISTERS 59 (odd melon Street P.O.Box 598, Holliday,Texas 76366 Quincy. Massachusetts 02169 PYTHIAN Supreme Chief JOYCE WRIGHT www.pythias.org INTERNATIONAL 22 Main Street Plaistovv, New Hampshire 03865 SUPREME LODGE OFFICERS VOLUME 101 • 2001 • ISSUE #3 Phone: 603-382-5715 Supreme Chancellor ... BOBBY G. CROWE e-mail [email protected] 330 N. Front Street Supreme Senior .GEORGIA BYRD Rockwood. -

A Souvenir of Massachusetts Legislators

^5? douvegir s* A SOUVENIR OF Massachusetts Legislators 1907 VOLUME XVI [I^ued Annually.] A. M. BRIDGMAN, STOUGHTON, MASS. Copyrighted by A. M. BRIDGMA>" 1907 Half-tones of Portraits and Interiors from Elmer Chickering the -'Royal Photographer," 21 West Street, Boston, Mass. Half tones of Groups from the Union Engraving Company, No. 338 Washington Street. Boston. The paper in this Souvenir is from the Jordan Paper Company. 524 Atlantic Avenue, Boston. Ma—. Composition and Presswork by the Memorial Press. Plymouth. Mass. PREFACE. It has become an axiom that every Legislature has its own special ana peculiar features. "Sufficient unto the (legislative) day is the evil there- of." Fortunately the Legislature of 1!)07. in sharp contrast with most of recent years, had no "investigation," although it came perilously near one. Never before was there a single measure involving so vast financial interests as the legislation involving the proposed union, or "merging," of the New York, Xew Haven & Hartford Railroad Company with that of the Boston & Maine; and certainly no legislative hearing ever before had before it within the same hour two railroad presidents of so great influ- ence as President Mellen of the former and President Tuttle of the lat- ter, both of whom were before the committee on railroads on the same afternoon. This session was marked also by the passage of the "anti- bucket-shop" legislation, and of acts to enable savings hanks to furnish life msurance at cost, and to compel one day's rest in seven as well as to perfect the eight-hour law in accordance with the wishes of organized labor. -

Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 05-03-1893 New Mexican Printing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 5-3-1893 Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 05-03-1893 New Mexican Printing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Company. "Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, 05-03-1893." (1893). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ sfnm_news/4387 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i.L. a. t )i -- A JL ,.iA --A. Q FE X VOL. 30. SANTA FE, N. M., WEDNESDAY. MAY 3, 1893. NO. 64. GRIST FROM GRANT. BRIEF IIRINGS-:- - A IsJ Readable Paragraphs Gathered by a E-- h REFRIGER Man on CO of the Went. New Mexican Pythian, the Road. Globe, Ariz., May 8. The Arizona 4 fytmans met in annual grand session J a 1 h O Correspondence New Mexican. L.. O B. r I P3 a California's JUelegation. Dbmino, May 8. Mr. Thos. Pheby . pq P2 E gH 8as Fbancisoo, May 8. The California on Monday brought down from George- contingent to the Indianapolis Interna town a car load of ore from his leased OSPowdef J 3S tionul Y. M. C. A. convention leaves on a o c pZ mines. There were thirty-tw- parcels of - 3 6-- 1 a special train for the east The oul "re Cream of Tartar Powder. -

Men of Affairs of Houston and Environs : a Newspaper Reference Work

^ 1Xctt)S|japer :ia;jg« '*ri'!iT Pi HMiMlhuCTII MEN OF AFFAIRS ;. AND REPRESEI^TaTIVE INSTITUTIONS OF HOUSTON AND ENVIRONS Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2011 witii funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/menofaffairsofhoOOhous ^ A Newspaper Reference Work mmm m TIHIE IHIOPSTOM FEESS CLUJE W. H. CoYLE & Company printers and stationers Houston. Texas f 39 H (*) ^ e 5 -^1 3 H fo ^ HE HOUSTON PRESS CLUB " herewith presents a book of photographs and hfe sketches of business and professional men of Houston and environs—men who are performing their share in the world's work. Our purpose, rather than to give any citizen or enterprise an undue amount of publicity, IS to provide for metropolitan newspaper libraries throughout the coun- try a work of reference on Houston citizens. All vital facts in the biographies have been furnished by the subjects themselves; so that this book is as nearly correct as anything of the sort ever published. May 1 St, 1913 (5) r A Newspaper R e f e e n c e Work HARRY T. WARNER PRESIDENT HOUSTON PRESS CLUB ARRY T. WARNER, first and incumbent president _n. of the Houston Press Club, managing editor of the Houston Post, was born at A'lontgomery, Alabama, and at an early age was brought by his parents to Texas; entered the newspaper business at 12 years of age at Austin, Texas, as a galley boy on the Austin States- rnan (1882); served his time as a printer; made a tour of the principal cities of Texas and of the East and then became con- nected with the editorial department of the Houston Post, with which paper he has remained in various managerial capacities for twent>' years. -

A Souvenir of Massachusetts Legislators

V , ;-. :.--.' CW^'^SWiNN lisfiliit ' WltitliS X£ wy j& f£ '= A SOUVENIR OF Massachusetts Legislators 1909 VOLU M E X V I I I (issued Annually) A. M. BRIDGMAN STOUGHTON, MASS. Al VAll few J9L*n ON A. M. BRIDGMAN, 1909. Half-tones of Portraits and Interiors from Elmer dickering, "The Royal Photographer," 21 West Street. Boston, Mass. Half-tones of Groups from W. J. Dobinson Engraving Co., No. 297 Wash- ington Street, Boston, Mass. Composition and Presswork by the Jamaica Printing Company, Jamaica Plain, Mass. i ss-. PREFACE /909 The Legislature of 1909 will easily rank as a "double-header." It is entitled to this distinction by reascn cf the prominence cf the hills to revise the charter cf the city of Boston and to incorporate the Railroad Ih lding Company to take over the st< ck of the Boston & Maine Railroad Company, and of other companies, if deemed advisable. The former of these measures was made, practically, a political measure, while the latter was marked by an entire absence of party lines in its advocacy and oppo- sition. The results to follow from either will lie the only means cf deter- mining the relative or absolute value to the state of either or of both. The labor, liquor, and milk measures, this year, were not of marked im- portance in their final outcome. There seemed, in the end. a feeling that the existing legislation should not he materially altered. The automobile legislation was materially changed and in the direction of more safety for the general public as against speed maniacs and other offenders against travelers. -

THE TOWPATH Published Quarterly (January - April - July - October) By

THE TOWPATH Published quarterly (January - April - July - October) by NEW BREMEN HISTORIC ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 73 - New Bremen, Ohio 45869-0073 (Founded in 1973) • MUSEUM located at 120 N. Main St. • VISITING HOURS: 2:00-4:00 p.m. Sundays - June, July, August (The Luelleman House) (Or anytime, by Appointment) DUES: $8.00 Per year / Per person (Life Membership: $75.00 Per person) April - 1999 1999 ANNUAL DINNER & PROGRAM Our annual dinner and program was held on Monday, March 15, 1999 at Faith Alliance Church on N.B./N.K. Road. The roast beef dinner was cooked by Ruth Krieg, one of our area's most popular cooks, and was served at 6:30 pm. by the Faith Alliance Youth Group and their leaders, Keith and Vonda Malone. Spring table decorations were furnished by Paul Headapohl. Approximately 125 attended. This year's program was given by Glenna Meckstroth of New Knoxville, who recently published a book, “Tales from Great-Grandpa’s Trunk.” Glenna had some of her books for sale and autographed those purchased. (If you would like a copy of Glenna's book, you may contact her at P.O. Box 502 - New Knoxville, Ohio 45871 for further information.) New and existing officers were introduced. Dru Meyer will be the new President, replacing outgoing President Doug Harrod. Jerry Braun will be Vice- President, Dorothy Hertenstein will be the new Secretary, and Tom Braun will continue as Treasurer and Genealogist. Two new Trustees are Jason This (replacing Martha Plattner, who resigned last fall) and Lawrence Egbert (replacing outgoing Trustee, Doug Harrod.) MEMBERSHIP DUES 1ST ANNUAL N.B.H.A. -

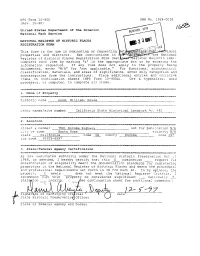

___Ft-9 7 Signature of Certifying Of

NFS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10--90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting properties and districts. See instructions in PloW^-tlp^^ the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Nat\&aa*iTregi3ter Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategcries from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a) . Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Hood, William, House other names/site number California State Historical Landmark No. 69; Location street & number 7501 Sonoma Highway____ _____ __ not for publication N/A city or town _ ____Santa Rosa___ ____ _ _ __ _______ __ vicinity N/A state California __ __ code CA county _ _Sg_nom_a__ ___ _ code 0_97 zic code" " "95409-6597 State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1936, as amended, 1 hereby certify that this X_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set. forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Western Maryland Room Vertical File Collection Catalog

Western Maryland Room Vertical File Collection Page 1 Inventoried in 1999, and updated May 2009, by Marsha L. Fuller,CG. Updated July 2013 by Klara Shives, Graduate Intern. Catalog: File Name Description Date Orig Cross Reference AAUW Allegany Co., MD Growing Up Near Oldtown 2000 Deffinbaugh Memoirs Allegany Co., MD The War for The British Empire in Allegany County 1969 x Allegany Co., MD Pioneer Settlers of Flintstone 1986 Allegany Co., MD Ancestral History of Thomas F. Myers 1965 x Allegany Co., MD Sesquicentennial - Frostburg, MD 1962 x Allegany Co., MD Harmony Castle No.3 - Knights of the Mystic Chains 1894 x Midland, MD Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ashmon Sorrell's Tombstone 2007 Civil War Allegany Co., MD (Box) The Heart of Western Maryland Allegany Co., MD (Box) Kelly-Springfield Tire Co. 1962 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ku Klux Klan 2008 Albert Feldstein Allegany Co., MD (Box) LaVale Toll House Allegany Co., MD (Box) List of Settlers in Allegany County 1787 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Mills, Grist and Flour Allegany Co., MD (Box) Miscellaneous clippings 1910-1932 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Names of towns, origin Allegany Co., MD (Box) National Highway - colored print Allegany Co., MD (Box) Old Allegany - A Century and A Half into the Past 1889 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Old Pictures of Allegany Co. 1981 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Ordeal in Twiggs Cave 1975 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Photographs of Western Maryland 1860-1925 1860-1925 Allegany Co., MD (Box) Piedmont Coal and Iron Company, Barton, MD (6) 1870s x Allegany Co., MD (Box) Pioneer log cabin Allegany