Using Local Knowledge to Guide Coconut Crab (Birgus Latro) Scientific Research in Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Severe Tc Gita (Cat4) Passes Just South of Ono

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No.35 5pm, Tuesday 13 February 2018 SEVERE TC GITA (CAT4) PASSES JUST SOUTH OF ONO Severe TC Gita (Category 4) entered Fiji Waters this morning and passed just south of Ono-i- lau at around 1.30pm this afternoon. Hurricane force winds of 68 knots and maximum momentary gusts of 84 knots were recorded at Ono-i-lau at 2pm this afternoon as TC Gita tracked westward. Vanuabalavu also recorded strong and gusty winds (Table 1). Severe “TC Gita” was located near 21.2 degrees south latitude and 178.9 degrees west longitude or about 60km south-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 390km southeast of Kadavu at 3pm this afternoon. It continues to move westward at about 25km/hr and expected to continue on this track and gradually turn west-southwest. On its projected path, Severe TC Gita is predicted to be located about 140km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 300km southeast of Kadavu around 8pm tonight. By 2am tomorrow morning, Severe TC Gita is expected to be located about 240km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau and 250km southeast of Kadavu and the following warnings remains in force: A “Hurricane Warning” remains in force for Ono-i-lau and Vatoa; A “Storm Warning” remains in force for the rest of Southern Lau group; A “Gale Warning” remains in force for Matuku, Totoya, Moala , Kadavu and nearby smaller islands and is now in force for Lakeba and Nayau; A “Strong Wind Warning” remains in force for Central Lau Group, Lomaiviti Group, southern half of Viti Levu and is now in force for rest of Fiji. -

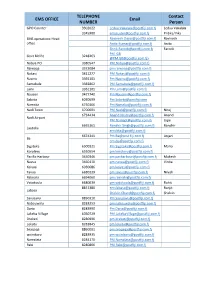

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Fiji: Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston Situation Report No

Fiji: Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston Situation Report No. 8 (as of 28 February 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific (ROP) in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 27 to 28 February 2016. The next report will be issued on or around 29 February 2016. Highlights On 20 and 21 February Category 5 Severe Tropical Cyclone Winston cut a path of destruction across Fiji. The cyclone is estimated to be one of the most severe ever to hit the South Pacific. The Fiji Government estimates almost 350,000 people living in the cyclone’s path could have been affected (180,000 men and 170 000 women). 5 6 42 people have been confirmed dead. 4 1,177 schools and early childhood education centres (ECEs) to re-open around Fiji. Winston 12 2 8 Total damage bill estimated at more than FJ$1billion or 10 9 1 almost half a billion USD. 3 11 7 87,000 households targeted for relief in 12 priority areas across Fiji. !^ Suva More than Population Density Government priority areas 51,000 for emergency response 1177 More densely populated 42 people still schools and early are shown above in red Confirmed fatalities sheltering in childhood centres and are numbered in order evacuation centres set to open Less densely populated of priority Sit Rep Sources: Fiji Government, Fiji NEOC/NDMO, PHT Partners, NGO Community, NZ Government. Datasets available in HDX at http://data.hdx.rwlabs.org. Situation Overview Food security is becoming an issue with crops ruined and markets either destroyed or inaccessible in many affected areas because of the cyclone. -

Tui Tai Expeditions One of the World's Only Truly All-Inclusive

tui tai expeditions We hope you’ll join us for the trip of a lifetime, during which you’ll visit remote beaches, snor- kel over incredible reefs, kayak to local villages, and experience the most breathtaking locations across Northern Fiji. The Tui Tai Expeditions takes guests to places they never imagined, the natural beauty of Fiji, and the kindness and warmth of the Fijian people. Tui Tai Expeditions is the premier adventure experience in the South Pacific. one of the world’s only truly all-inclusive expeditions When you’re enjoying a luxury-adventure expedition on Tui Tai, you don’t ever have to think about the details of extra charges because there aren’t any. We’ve designed our service to be All-inclusive. Not “all inclusive” as some use the term, followed by a bunch of fine print explaining what isn’t included. We mean that everything is included: every service, mixed drink, glass of wine or beer, every meal, all scuba diving (even dive courses), snorkeling, kayaking, spa treatments - everything. Once you board Tui Tai, the details are in our hands, and your only responsibility is to have the experience of a lifetime. “World’s Sexiest Cruise Ships” Conde Nast luxury that doesn’t get adventure that doesn’t pacific cultural triangle rabi island Micronesian people, originally in the way of adventure get in the way of luxury Tui Tai is the only luxury-adventure ship oper- from Banaba in equatorial Kiribati. The word luxury can be defined in many ways. Like luxury, adventure can be defined many ating in the Pacific Cultural Triangle, providing Settled on Rabi Island in Fiji on On Tui Tai, luxury means that everything has ways. -

EXPEDITIONS Summary Calendar Month by Month

EXPEDITIONS Summary calendar month by month WINTER 2018/2019 SEPTEMBER DECEMBER MARCH 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 2019 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 28th 14 9822 Colombo > Mahé 01st 7 8848 North Central Itinerary 02nd 7 8909 Western Itinerary 08th 7 8849 Western Itinerary 09th 7 8910 North Central Itinerary 16th 7 Western Itinerary OCTOBER 15th 7 8850 North Central Itinerary 8911 23rd 7 8912 North Central Itinerary 2018 DAYS SHIP VOYAGE EMBARK/DISEMBARK 22nd 7 8851 Western Itinerary 30th 7 8913 Western Itinerary GALÁPAGOS ISLANDS 29th 7 8852 North Central Itinerary ASIA 06th 7 8840 North Central Itinerary ANTARCTICA 05th 15 9905 Yangon > Benoa (Bali) 13th 7 Western Itinerary 8841 02nd 10 1827 Ushuaia Roundtrip 20th 16 9906 Benoa (Bali) > Darwin 20th 7 8842 North Central Itinerary 07th 10 7824 Ushuaia Roundtrip 27th 7 8843 Western Itinerary ANTARCTICA 12th 10 1828 Ushuaia Roundtrip 07th 21 1907 Ushuaia > Cape Town AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN 17th 18 7825 Ushuaia Roundtrip CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA 12th 11 9823 Mahé Roundtrip 22nd 15 1829 Ushuaia Roundtrip 07th 9 7905 Valparaíso > Easter Island CENTRAL & SOUTH AMERICA AFRICA & THE INDIAN OCEAN SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS 03th 12 1822 Nassau > Colon 13th 6 9828A Durban > Maputo 16th 14 7906 Easter Island > Papeete (Tahiti) 15th 11 1823 Colon > Callao (Lima) 30th 13 Papeete (Tahiti) > Lautoka 19th 17 9829 Maputo > Mahé 7907 26th 16 1824 Callao (Lima) > Punta Arenas AFRICA & THE INDIAN -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Identifying Corals Displaying Aberrant Behavior in Fiji's Lau Archipelago

RESEARCH ARTICLE Identifying corals displaying aberrant behavior in Fiji's Lau Archipelago Anderson B. Mayfield1,2,3*, Chii-Shiarng Chen1,3,4,5, Alexandra C. Dempsey2 1 National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Checheng, Pingtung, Taiwan, 2 Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Annapolis, MD, United States of America, 3 Taiwan Coral Research Center, Checheng, Pingtung, Taiwan, 4 Graduate Institute of Marine Biotechnology, National Dong Hwa University, Checheng, Pingtung, Taiwan, 5 Department of Marine Biotechnology and Resources, National Sun Yat-Sen University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan * [email protected]. a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Given the numerous threats against Earth's coral reefs, there is an urgent need to develop means of assessing reef coral health on a proactive timescale. Molecular biomarkers may prove useful in this endeavor because their expression should theoretically undergo changes prior to visible signs of health decline, such as the breakdown of the coral-dinofla- OPEN ACCESS gellate (genus Symbiodinium) endosymbiosis. Herein 13 molecular- and physiological- scale biomarkers spanning both eukaryotic compartments of the anthozoan-Symbiodinium Citation: Mayfield AB, Chen C-S, Dempsey AC (2017) Identifying corals displaying aberrant mutualism were assessed across 70 pocilloporid coral colonies sampled from reefs of Fiji's behavior in Fiji's Lau Archipelago. PLoS ONE 12(5): easternmost province, Lau. Eleven colonies were identified as outliers upon employment of e0177267. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. a detection method based partially on the Mahalanobis distance; these corals were hypothe- pone.0177267 sized to have been displaying aberrant sub-cellular behavior with respect to their gene Editor: Christian R. Voolstra, King Abdullah expression signatures, as they were characterized not only by lower Symbiodinium densi- University of Science and Technology, SAUDI ties, but also by higher levels of expression of several stress-targeted genes. -

Republic of the Fiji Islands State Cedaw 2Nd, 3Rd & 4Th Periodic Report

ANNEXES TO THE COMBINED SECOND, THIRD AND FOURTH PERIODIC REPORT OF FIJI (CEDAW/C/FJI/2-4) REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS STATE CEDAW 2ND, 3RD & 4TH PERIODIC REPORT NOVEMBER 2008 Annexes ANNEX 1 CONCLUDING COMMENTS CEDAW RECOMMENDATION AND STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION in FIJI Concerns Recommendation Response 1.Constitution of 1997 does Proposed constitution In fact the Constitution covers not contain the definition of reform should address the ALL FORMS of Discrimination discrimination against women need to incorporate the in section 38(2). The definition of definition of discrimination discrimination is contained in the Human Rights Commission Act at section 17 (1) and (2). 2. Absence of effective The government to include The Human Rights Commission mechanisms to challenge a clear procedure for the Act 10/99 is Fiji’s EEO law- see discriminatory practices and enforcement of section 17 for application to the enforce the right to gender fundamental rights and private sphere and employment. equality guaranteed by the enact an EEO law to cover FHRC also handles complaints constitution in respect of the the actions of non-state by women on a range of issues. actions of public officials and actors. (Reports Attached as Annex 2). non-state actors. 3.CEDAW is not specified in Expansions of the FHRC’s NOT TRUE. FHRC has a broad, and the mandate of the Fiji Human mandate to include not specific, mandate and therefore Rights Commission and that its CEDAW and that the deals with all discrimination including not assured funds to continue commission is provided gender. In response to the Concluding its work with adequate resources Comments of the UN CEDAW from State funds. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

South Pacific Islands Expedition Cruise

PAPEETE TO LAUTOKA: SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS EXPEDITION CRUISE Join us to look for the Pearls of the Pacific. Starting in Tahiti, Silver Explorer will sail through Polynesia via the Cook Islands, Niue and Tonga and will visit several island gems in Fiji. Discover black pearls and underwater wonders, and explore blue lagoons and raised coral islands. Swim with rays and sharks, watch for dolphins and look for seabird colonies on isolated islands in some of Polynesia’s and Melanesia’s best and least known lagoons, or relax on beautiful beaches. Interact with local communities and experience the legendary friendliness of the Pacific Islanders. Throughout the voyage, learn about the history, geology, wildlife and botany of these locations from lecture presentations offered by your knowledgeable onboard Expedition Team. ITINERARY Day 1 PAPEETE (TAHITI) Papeete will be your gateway to the tropical paradise of French Polynesia, where islands fringed with gorgeous beaches and turquoise ocean await to soothe the soul. This spirited city is the capital of French Polynesia, and serves as a superb base for onward exploration of Tahiti – an island of breathtaking landscapes and oceanic vistas. Wonderful lagoons of crisp, clear water beg to be snorkelled, stunning black beaches and blowholes pay tribute to the island's volcanic heritage, and lush green mountains beckon you inland on adventures, as you explore extraordinary Tahiti. Day 2 BORA BORA (SOCIETY ISLANDS) 01432 507 280 (within UK) [email protected] | small-cruise-ships.com Simply saying the name Bora Bora is usually enough to induce ashore, the whole community generally turns out to meet gasps of jealousy, as images of milky blue water, sparkling visitors as it is a rare occurrence.