Turtle Biodiversity and Conservation Joseph C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Sea Turtle in the New England Aquarium Has Been in Captivity Since 1970, and Is Believed to Be Around 80 Years Old (NEAQ 2013)

Species Status Assessment Class: Reptilia Family: Cheloniidae Scientific Name: Chelonia mydas Common Name: Green turtle Species synopsis: The green turtle is a marine turtle that was originally described by Linnaeus in 1758 as Testudo mydas. In 1868 Marie Firmin Bocourt named a new species of sea turtle Chelonia agassizii. It was later determined that these represented the same species, and the name became Chelonia mydas. In New York, the green turtle can be found from July – November, with individuals occasionally found cold-stunned in the winter months (Berry et al. 1997, Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles are sighted most frequently in association with sea grass beds off the eastern side of Long Island. They are observed with some regularity in the Peconic Estuary (Morreale and Standora 1998). Green turtles experienced a drastic decline throughout their range during the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of human exploitation and anthropogenic habitat degradation (NMFS and USFWS 1991). In recent years, some populations, including the Florida nesting population, have been experiencing some signs of increase (NMFS and USFWS 2007). Trends have not been analyzed in New York; a mark-recapture study performed in the state from 1987 – 1992 found that there seemed to be more green turtles at the end of the study period (Berry et al. 1997). However, changes in temperature have lead to an increase in the number of cold stunned green turtles in recent years (NMFS, Riverhead Foundation). Also, this year a record number of nests were observed at nesting beaches in Flordia (Mote Marine Laboratory 2013). 1 I. -

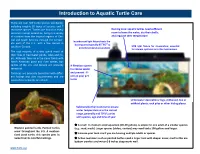

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Spirorchiidiasis in Stranded Loggerhead Caretta Caretta and Green Turtles Chelonia Mydas in Florida (USA): Host Pathology and Significance

Vol. 89: 237–259, 2010 DISEASES OF AQUATIC ORGANISMS Published April 12 doi: 10.3354/dao02195 Dis Aquat Org OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spirorchiidiasis in stranded loggerhead Caretta caretta and green turtles Chelonia mydas in Florida (USA): host pathology and significance Brian A. Stacy1,*, Allen M. Foley2, Ellis Greiner3, Lawrence H. Herbst4, Alan Bolten5, Paul Klein6, Charles A. Manire7, Elliott R. Jacobson1 1University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Large Animal Clinical Sciences, PO Box 100136, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 2Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, Jacksonville Field Laboratory, 370 Zoo Parkway, Jacksonville, Florida 32221, USA 3University of Florida, College of Veterinary Medicine, Infectious Diseases and Pathology, PO Box 110880, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 4Department of Pathology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York 10461, USA 5Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida, PO Box 118525, Gainesville, Florida 32611, USA 6Department of Pathology, Immunology, and Laboratory Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32610, USA 7Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Florida 34236, USA ABSTRACT: Spirorchiid trematodes are implicated as an important cause of stranding and mortality in sea turtles worldwide. However, the impact of these parasites on sea turtle health is poorly understood due to biases in study populations and limited or missing data for some host species and regions, includ- ing the southeastern United States. We examined necropsy findings and parasitological data from 89 log- gerhead Caretta caretta and 59 green turtles Chelonia mydas that were found dead or moribund (i.e. stranded) in Florida (USA) and evaluated the role of spirorchiidiasis in the cause of death. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae. -

'Camouflage' Their Nests but Avoid Them and Create a Decoy Trail

Buried treasure—marine turtles do not ‘disguise’ or royalsocietypublishing.org/journal/rsos ‘camouflage’ their nests but avoid them and create a Research Cite this article: Burns TJ, Thomson RR, McLaren decoy trail RA, Rawlinson J, McMillan E, Davidson H, Kennedy — MW. 2020 Buried treasure marine turtles do not † ‘disguise’ or ‘camouflage’ their nests but avoid Thomas J. Burns , Rory R. Thomson, Rosemary them and create a decoy trail. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7: 200327. A. McLaren, Jack Rawlinson, Euan McMillan, http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200327 Hannah Davidson and Malcolm W. Kennedy Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, and School of Life Sciences, Graham Kerr Building, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Received: 27 February 2020 University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Accepted: 6 April 2020 TJB, 0000-0003-0408-8014; MWK, 0000-0002-0970-5264 After laying their eggs and refilling the egg chamber, sea Subject Category: turtles scatter sand extensively around the nest site. This is presumed to camouflage the nest, or optimize local conditions Organismal and Evolutionary Biology for egg development, but a consensus on its function is Subject Areas: lacking. We quantified activity and mapped the movements of hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and leatherback (Dermochelys behaviour coriacea) turtles during sand-scattering. For leatherbacks, we also recorded activity at each sand-scattering position. Keywords: For hawksbills, we recorded breathing rates during nesting as hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, leatherback an indicator of metabolic investment and compared with turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, nesting behaviour published values for leatherbacks. Temporal and inferred metabolic investment in sand-scattering was substantial for both species. -

Seasonality and Site Fidelity of an Insular Population of Texas Diamondback Terrapins As Determined by Acoustic Telemetry

You may use the information and images contained in this document for non-commercial, personal, or educational purposes only, provided that you (1) do not modify such information and (2) include proper citation. If material is used for other purposes, you must obtain written permission from the author(s) to use the copyrighted material prior to its use. Staying Close to Home: Seasonality and Site Fidelity of an Insular Population of Texas Diamondback Terrapins as Determined by Acoustic Telemetry Mandi Gordon*, Jenny W. Oakley, George J. Guillen Environmental Institute of Houston University of Houston – Clear Lake 2700 Bay Area Blvd. Houston, Texas, 77584 *[email protected] 8th Triennial Diamondback Terrapin Working Group Meeting Wilmington, NC; October 11-13, 2019 Abstract As critical saltmarsh habitat declines and severe weather events (hurricanes, drought, etc.) become more frequent, it is important for resource managers to understand how species of greatest conservation need are utilizing available habitat. In highly urbanized bays, such as Galveston Bay, available marsh habitat is limited or declining and Diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) populations exist in more isolated areas than other populations along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts. To determine seasonality and site fidelity of an insular population of terrapin, an acoustic array was installed using Vemco acoustic receivers. From March 2009-April 2014, 39 terrapin (33 female; 6 male) were fitted with V13-1H transmitters. Transmitters were detected every year and, across all years, every month. Over 62 consecutive months of monitoring, 9 showed no detections (Jan 2010; Sep 2011, Nov 2012-Feb 2013; May 2013; Jan-Feb 2014), all correlated with major weather events. -

The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys Coriacea

16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 13-16 Coll. and Res. (2003) 16: 17-26 17 claw ending as knob; empodium divided, 5 rayed. without a short line on each side, admedian lines The Latest Record of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys with a semicircular line extending to lateral sides, Opisthosoma : dorsum with median ridge shorter and the 5-rayed empodium. coriacea) from Eastern Taiwan than submedian ridges, dorsally with about 51 rings, ventrally with about 53 microtuberculate Chun-Hsiang Chang1,2*, Chern-Mei Jang3, and Yen-Nien Cheng2 REFERENCES rings; 1st 3 dorsal annuli 9 long; lateral setae (c2) 10 long, Lt-Lt 44 apart, Lt\Vt1 38, Lt-Vt1 25; 1st 1Department of Biology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, UK Keifer, H.H. 1977. Eriophyid studies C-13. ARS- ventral setae (d) 17 long, Vt1-Vt1 19 apart, 2Department of Geology, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung, Taiwan 404 R.O.C. USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. Vt1\Vt2 28, Vt1-Vt2 25; 2nd ventral setae (e) 17 3 Keifer, H.H. 1978. Eriophyid studies C-15. ARS- Department of Collection Management, National Museum of Natural Science, Taichung Taiwan 404 long, Vt2-Vt2 10 apart, Vt2\Vt3 40, Vt2-Vt3 38; USDA, Washington, DC. 24pp. R.O.C. 3rd ventral setae (f) 14 long, Vt3-Vt3 16 apart; Huang, K.W. 1999. The species and geographic accessory setae (h1) present. variation of eriophyoid mites on Yushania Coverflap: 19 wide, 12 long, with about 9 niitakayamensis of Taiwan. Proc. Symp. In (Received June 30, 2003; Accepted September 16, 2003) longitudinal ridges, genital setae (3a) 6 long, Gt- Insect Systematics and Evolution. -

Sea Turtles : the Importance of Sea Turtles to Marine Ecosystems

PHOTO TIM CALVER WHY HEALTHY OCEANS NEED SEA TURTLES : THE IMPORTANCE OF SEA TURTLES TO MARINE ECOSYSTEMS Wilson, E.G., Miller, K.L., Allison, D. and Magliocca, M. oceana.org/seaturtles S E L T R U T Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Karen Bjorndal for her review of this report. We would also like to thank The Streisand Foundation for their support of Oceana’s work to save sea turtles. PHOTO MICHAEL STUBBLEFIELD OCEANA | Protecting the World’s Oceans TABLE OF CONTENTS WHY HEALTHY OCEANS NEED SEA TURTLES 3 Executive Summary 4 U.S. Sea Turtles 5 Importance of Sea Turtles to Healthy Oceans 6 Maintaining Habitat Importance of Green Sea Turtles on Seagrass Beds Impact of Hawksbill Sea Turtles on Coral Reefs Benefit of Sea Turtles to Beach Dunes 9 Maintaining a Balanced Food Web Sea Turtles and Jellyfish Sea Turtles Provide Food for Fish 11 Nutrient Cycling Loggerheads Benefit Ocean Floor Ecosystems Sea Turtles Improve Nesting Beaches 12 Providing Habitat 14 The Risk of Ecological Extinction 15 Conclusions oceana.org/seaturtles 1 S E L T R U T PHOTO TIM CALVER 2 OCEANA | Protecting the World’s Oceans EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sea turtles have played vital roles in maintaining the health of the world’s oceans for more than 100 million years. These roles range from maintaining productive coral reef ecosystems to transporting essential nutrients from the oceans to beaches and coastal dunes. Major changes have occurred in the oceans because sea turtles have been virtually eliminated from many areas of the globe. Commercial fishing, loss of nesting habitat and climate change are among the human-caused threats pushing sea turtles towards extinction. -

Morphological Variation in Leatherback (Dermochelys Coriacea) Hatchlings at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, US Virgin Islands

Vol. 41: 361–372, 2020 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published April 9 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01030 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Morphological variation in leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) hatchlings at Sandy Point National Wildlife Refuge, US Virgin Islands Shreya M. Banerjee1,6,*, Amy Frey2, Carolyn M. Kurle3, Justin R. Perrault4,7, Kelly R. Stewart5 1Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA, ORCID: 0000-0003-1210-2162 2Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA 3Division of Biological Sciences, Ecology, Behavior, and Evolution Section, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA, ORCID: 0000-0003-1121-9924 4Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA 5The Ocean Foundation, Washington, DC 20036, USA, ORCID: 0000-0002-8673-5192 6Present address: Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA 7Present address: Loggerhead Marinelife Center, Juno Beach, FL 33408, USA, ORCID: 0000-0002-5046-6701 ABSTRACT: Understanding species’ mating systems provides important information about their ecology, life history, and behavior. Direct observations of mating behaviors can be challenging, but molecular techniques can reveal information about mating systems and paternal identity in difficult-to-observe species such as sea turtles. Genetic markers can be used to assess the pater- nity of a clutch and to assign hatchlings to a father. Leatherback turtles Dermochelys coriacea sometimes mate with multiple individuals, resulting in clutches with mixed paternity; however, the effects of multiple paternity on hatchling quality are unclear.