Violence, Partition and Locality of Lahore: a Critical Reappraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Un-Paid Dividend

Descon Oxychem Limited DETAIL OF UNPAID DIVIDEND AMOUNT(S) IN PKR Dated as on: 18-Dec-20 Folio Shareholder Adresses No. of Shares Dividend 301, HAFSA SQUARE, BLOCK-3,, PLOT NO: 9, 208/32439/C ADAM KHALID MCHS., KARACHI-EAST, KARACHI 25,000 21,250 513/20972/C KHALID RAFIQUE MIRZA 5/6 B,PRESS COLONY G7/4 ISLAMABAD 20,000 17,000 B-13, SALMA VILLA, RUBY STREET,GARDEN 307/69264/C SHAN WEST, KARACHI 20,000 17,000 201 MR. AAMIR MALIK 115-BB, DHA, LAHORE. 25,500 15,300 18 MR. ABDUL KHALIQUE KHAN HOUSE NO.558/11, BLOCK W, DHA, LAHORE. 25,500 15,300 282 MR. SAAD ULLAH KHAN HOUSE NO.49/1, DHA, SECTOR 5, LAHORE. 20,000 12,000 269 MR. BILAL AHMAD BAJWA HOUSE NO.C-9/2-1485, KARAK ROAD, LAHORE. 20,000 12,000 HOUSE NO.258, SECTOR A1, TOWNSHIP, 105 MR. ATEEQ UZ ZAMAN KHAN LAHORE. 19,000 11,400 HOUSE NO.53-D, RIZWAN BLOCK, AWAN TOWN, 96 MR. AHMAD FAROOQ LAHORE. 19,000 11,400 HOUSE NO.42, LANE 3, ASKARIA COLONY, 103 MR. MUHAMMAD ANEES PHASE 1, MULTAN CANTT. 18,000 10,800 HOUSE NO.53/1, BLOCK C1, TOWNSHIP, 20 MR. MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD JAMEEL LAHORE. 18,000 10,800 6122/18275/C AHMAD HUSSAIN KAZI HOUSE # 100, HILLSIDE ROAD, E-7. ISLAMABAD 15,000 9,000 59 MR. ZUBAIR UL HASSAN HOUSE NO.10-22, ABID MAJID ROAD, LAHORE. 19,000 8,550 92 MR. ASAD AZHAR HOUSE NO.747-Z, DHA, LAHORE. 19,000 8,550 7161/42148/C MUHAMMAD KASHIF 50-G, BLOCK-2,P.E.C.H.S KARACHI 10,000 8,500 56, A-STREET, PHJASE 5, OFF KHAYABAN-E- 6700/23126/C HIBAH KHAN SHUJAAT D.H.A KARACHI 10,000 8,500 HOUSE # 164, ABUBAKAR BLOCK, GARDEN 12211/597/C JAVED AHMED TOWN, LAHORE 9,000 7,650 HOUSE # P-47 STREET # 4 JAIL ROAD RAFIQ 5801/16681/C MUHAMMAD YOUSAF COLONY FAISALABAD 9,000 7,650 FLAT # B-1, AL YOUSUF GARDEN,, GHULAM HUSSAIN QASIM ROAD, GARDEN WEST, 3277/77663/IIA IMRAN KARACHI 10,000 7,000 67 MR. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Caste, Trade Or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume: 34, No. 01, January – June 2021 Ayesha Farooq * Caste, Trade or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab Abstract Dynamics of caste have modified over time due to occupational changes, economic positions and religious enlightenment. However, it is not entirely replaced by any new stratification structure, resulting in much confusion regarding the adopted caste titles in the community. The present research has been conducted in a village named Mohla in the Punjab, Pakistan. Findings revealed resistance of young generation towards the existing caste system and they were recognized by trades of their forefather. Economic factor found important for such differences, besides education and migration. There has been fluidity of caste perception over generation and across social strata; young, educated, economically better off craftsmen and women condemned caste division whereas most of the landowners emphasized the importance of caste system. Shift in basis of social differentiation, role of chieftain has become negligible as majority of them tend to resolve their issues by themselves and go to police or courts. Keywords: Caste system, Class structure, social stratification, intergenerational differences, economics, migration, infrastructure. Introduction The present paper aims to assess stratification system in a rural community named Mohla, situated in District Gujrat of Punjab, Pakistan. Implications of caste on various aspects of social life are also observed. Eglar studied this village five decades ago and found caste stratification as foremost aspect in determining social status and life opportunities.1 In this study, we intend to look into the differences between old and young villager’s perception regarding caste system. -

Structural Violence Against Children in South Asia © Unicef Rosa 2018

STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA © UNICEF ROSA 2018 Cover Photo: Bangladesh, Jamalpur: Children and other community members watching an anti-child marriage drama performed by members of an Adolescent Club. © UNICEF/South Asia 2016/Bronstein The material in this report has been commissioned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) regional office in South Asia. UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this work do not imply an opinion on the legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. Permission to copy, disseminate or otherwise use information from this publication is granted so long as appropriate acknowledgement is given. The suggested citation is: United Nations Children’s Fund, Structural Violence against Children in South Asia, UNICEF, Kathmandu, 2018. STRUCTURAL VIOLENCE AGAINST CHILDREN IN SOUTH ASIA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS UNICEF would like to acknowledge Parveen from the University of Sheffield, Drs. Taveeshi Gupta with Fiona Samuels Ramya Subrahmanian of Know Violence in for their work in developing this report. The Childhood, and Enakshi Ganguly Thukral report was prepared under the guidance of of HAQ (Centre for Child Rights India). Kendra Gregson with Sheeba Harma of the From UNICEF, staff members representing United Nations Children's Fund Regional the fields of child protection, gender Office in South Asia. and research, provided important inputs informed by specific South Asia country This report benefited from the contribution contexts, programming and current violence of a distinguished reference group: research. In particular, from UNICEF we Susan Bissell of the Global Partnership would like to thank: Ann Rosemary Arnott, to End Violence against Children, Ingrid Roshni Basu, Ramiz Behbudov, Sarah Fitzgerald of United Nations Population Coleman, Shreyasi Jha, Aniruddha Kulkarni, Fund Asia and the Pacific region, Shireen Mary Catherine Maternowska and Eri Jejeebhoy of the Population Council, Ali Mathers Suzuki. -

DC Valuation Table (2018-19)

VALUATION TABLE URBAN WAGHA TOWN Residential 2018-19 Commercial 2018-19 # AREA Constructed Constructed Open Plot Open Plot property per property per Per Marla Per Marla sqft sqft ATTOKI AWAN, Bismillah , Al Raheem 1 Garden , Al Ahmed Garden etc (All 275,000 880 375,000 1,430 Residential) BAGHBANPURA (ALL TOWN / 2 375,000 880 700,000 1,430 SOCITIES) BAGRIAN SYEDAN (ALL TOWN / 3 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 SOCITIES) CHAK RAMPURA (Garision Garden, 4 275,000 880 400,000 1,430 Rehmat Town etc) (All Residential) CHAK DHEERA (ALL TOWN / 5 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIETIES) DAROGHAWALA CHOWK TO RING 6 500,000 880 750,000 1,430 ROAD MEHMOOD BOOTI 7 DAVI PURA (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) 275,000 880 350,000 1,430 FATEH JANG SINGH WALA (ALL TOWN 8 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) GOBIND PURA (ALL TOWNS / 9 400,000 880 1,000,000 1,430 SOCIEITIES) HANDU, Al Raheem, Masha Allah, 10 Gulshen Dawood,Al Ahmed Garden (ALL 250,000 880 350,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) JALLO, Al Hafeez, IBL Homes, Palm 11 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 Villas, Aziz Garden etc KHEERA, Aziz Garden, Canal Forts, Al 12 Hafeez Garden, Palm Villas (ALL TOWN 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 / SOCITIES) KOT DUNI CHAND Al Karim Garden, 13 Malik Nazir G Garden, Ghous Garden 250,000 880 400,000 1,430 (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) KOTLI GHASI Hanif Park, Garision Garden, Gulshen e Haider, Moeez Town & 14 250,000 880 500,000 1,430 New Bilal Gung H Scheme (ALL TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Al Wadood Garden (ALL 15 225,000 880 500,000 1,430 TOWN / SOCITIES) LAKHODAIR, Ring Road Par (ALL TOWN 16 75,000 880 200,000 -

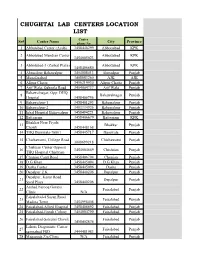

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Jammu and Kashmir Upgs 2018

State People Group Language Religion Population % Christian Jammu and Kashmir Adi Dravida Tamil Hinduism 20 0 Jammu and Kashmir Ahmadi Urdu Islam 70 0 Jammu and Kashmir Ansari Urdu Islam 320 0 Jammu and Kashmir Arain (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 9360 0 Jammu and Kashmir Arora (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 16830 0 Jammu and Kashmir Arora (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 580 0 Jammu and Kashmir Arora (Sikh traditions) Punjabi, Eastern Other / Small 3100 0 Jammu and Kashmir Awan Punjabi, Eastern Islam 3370 0 Jammu and Kashmir Badhai (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 250 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bafinda Dogri Islam 13330 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bagdi Hindi Hinduism 30 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bairagi (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism 9360 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bakkarwal Kashmiri Islam 113240 0.044154 Jammu and Kashmir Balti Balti Islam 51910 0.0963206 Jammu and Kashmir Bandukkhar Kashmiri Islam 690 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Agarwal Hindi Hinduism 15190 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Gahoi Hindi Hinduism 960 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Jaiswal Hindi Other / Small 90 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Kasaundhan Hindi Hinduism 1200 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Khandelwal Hindi Hinduism 60 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Mahajan Hindi Hinduism 2730 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Mahesri Hindi Hinduism 1140 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Mahur Hindi Hinduism 5770 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania Porwal Hindi Hinduism 860 0 Jammu and Kashmir Bania unspecified Hindi Hinduism 96590 0 Jammu and Kashmir Banjara (Muslim traditions) Urdu Islam 240 0 Jammu and Kashmir Barwala (Hindu traditions) Hindi Hinduism -

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

Second Lahore Biennale: Between the Sun and the Moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists

For Immediate Release 6 January 2020 Second Lahore Biennale: between the sun and the moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists Installed Across Cultural and Heritage Sites Throughout Lahore, Pakistan, from 26 January to 29 February 2020 Lahore, Pakistan—6 January 2020—The Lahore Biennale Foundation today revealed a list of over 70 participating artists for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale (LB02), running from 26 January through 29 February 2020. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, LB02: between the sun and the moon brings a plethora of artistic projects to cultural and heritage sites throughout the city of Lahore including more than 20 new commissions by artists from across the region and around the world, including Alia Farid, Diana Al-Hadid, Hassan Hajjaj, Haroon Mirza, Hajra Waheed and Simone Fattal, among many others. Other participating artists include Anwar Saeed, Rasheed Araeen and the late Madiha Aijaz. With a focus on the Global South, where ongoing social disaffection is being aggravated by climate change, LB02 responds to the cultural and ecological history of Lahore and aims to awaken awareness of humanity’s daunting contemporary predicament. Works presented in LB02 will explore human entanglement with the environment while revisiting traditional understandings of the self and their cosmological underpinnings. Inspiration for this thematic focus is drawn from intellectual and cultural exchange between South and West Asia. “For centuries, inhabitants of these regions oriented themselves with reference to the sun, the moon, and the constellations. -

Global Prayer Digest JAN–FEB 2021

Global Prayer Digest JAN–FEB 2021 Dear Praying Friends, We are officially in a new decade and a new era • Pray that this people group will be in awe of the Lord for His creation and realize that He is the only for Global Prayer Digest (GPD) readers. As of one worthy of worship and devotion. today, GPD is fully merged with Joshua Project’s Unreached of the Day’s (UOTD) digital prayer 2 Buriat People in Inner Mongolia, China tools, but we also have a shortened printed form within our sister publication, Mission Frontiers So God created human beings in His own (MF). MF offers readers the reasons why we need Gen 1:27 image. In the image of God He created movements to Christ, and we offer prayer materials them; male and female he created them. for movements to Christ among specific people The Buriat claim to be descended from either a grey groups. Is this a perfect combination or what? bull or a white swan; therefore their folk culture Pray on this decade!—Keith Carey, editor, UOTD features dancers imitating swans and other animals. They share many common traits and customs with Note: Scripture references are from the New Living Mongols. They are Buddhist, though the shaman is Translation (NLT) unless otherwise indicated. a highly regarded member in their culture. • Ask God to send loving, bold ambassadors of Christ to the Buriats and other peoples in this region. Please ask God to help the Buriats find their identity DIGEST PRAYER GLOBAL in Him. May the believers become effective and fruitful in sharing and discussing Bible stories with their own and other families. -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO.