NWLR (Pt 1512)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chukwudi Ugwanyi V Federal Republic of Nigeria

In the Supreme Court of Nigeria On Friday, the 23rd day of March 2012 Before their Lordships Walter Samuel Nkanu Onnoghen ...... Justice Supreme Court Ibrahim Tanko Muhammad ...... Justice Supreme Court Olufunlola Oyelola Adekeye ...... Justice Supreme Court Bode Rhodes-Vivour ...... Justice Supreme Court Mary Ukaego Perter-Odili ...... Justice Supreme Court SC.190/2010 Between Chukwudi Ugwanyi ...... Appellant And Federal Republic of Nigeria ...... Respondent Judgment of the Court Delivered by Bode RhodesVivour. JSC The appellant was charged and arraigned on a one count charge which reads: That you Chukwudi Ugwanyi (M) 50 years of age, of No 4 Arowojobe Street, Onigbongbo Maryland, Lagos on or about the 17th November 2000 at Bodinga along Sokoto-Yauri Road, Sokoto within the jurisdiction of this Honourable Court, and without lawful authority had in your possession 26 kilograms of Indian Hemp otherwise known as cannabis sativa, a narcotic drug similar to Cocaine and Heroin and thereby committed an offence contrary to and punishable under section 10H of the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (Amendment) Act No 15 of 1992. Hobon, J of the Federal High Court, Sokoto Division presided. The appellant entered a not guilty plea. Two witnesses testified for the prosecution. Both of them are officers from the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA). The prosecution tendered in court the following items, which were admitted as Exhibits: A. Certificate of testing analysis B. Packing of substance Forms C. Request for scientific aid D1 - D12 Twelve wrapped Sellotaped bundles recovered from the appellant. E. Drug analysis Report dated 4/1/2005 E2. Transparent evidence pouch with substances feature and descriptions of the accused and the case. -

Bernard Ojeifo Longe V First Bank of Nigeria

In The Supreme Court of Nigeria On Friday, the 5th day of March 2010 Before Their Lordships Dahiru Musdapher ...... Justice, Supreme Court George Adesola Oguntade ...... Justice, Supreme Court Francis Fedode Tabai ...... Justice, Supreme Court Ibrahim Tanko Muhammad ...... Justice, Supreme Court Olufunlola Oyelola Adekeye ...... Justice, Supreme Court S.C. 116/2007 Between Bernard Ojeifo Longe ....... Appellant And First Bank of Nigeria Plc ....... Respondent Judgement of the Court Delivered by George Adesola Oguntade. J.S.C. The appellant was the plaintiff before the Federal High Court Lagos where on 4-07-02, he issued a Writ of Summons against the respondent as the defendant claiming the following reliefs: (i) A declaration that the Defendant's Board of Directors cannot lawfully hold any meeting of the said Board without giving notice thereof to the Plaintiff and accordingly all decisions taken at any such meeting is unlawful, invalid, null and void and incapable of having any legal consequence; (ii) A declaration that in particular the decision of the Defendant's Board of Directors held on the 13th of June 2002 to revoke the Plaintiff s appointment as Managing Director/Chief Executive is wrongful, unlawful, invalid, null and void and incapable of having any legal consequence; (iii) A declaration that any purported implementation of the said decision made by the Board on the 13th of June 2002 (including any appointment to the office held by the Plaintiff in the Defendant Company) is ineffective, unlawful and null and void; (iv) An order of injunction restraining the said Defendants from giving effect or continuing to give effect to any of the decisions of the Board mentioned in claims (i) and (ii) hereof without first complying with the mandatory procedural requirements stipulated in Section 266(3) of C.A.M.A. -

Law COMPANION Is Restricted by Territory, That Law Cannot Be Applied Outside That Territory

JOSEPH MORAH APPELLANT AND FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA RESPONDENT SC.160/2015 SUPREME COURT OF NIGERIA IBRAHIM TANKO MUHAMMAD JSC OLUKAYODE ARIWOOLA JSC KUMAI BAYANG AKA'AHS JSC (Delivered Lead Judgment) JOHN INYANG OKORO JSC PAUL ADAMULAW GALINJE COMPANION JSC AT ABUJA, ON FRIDAY, 23RD MARCH, 2018 COURT- Offence with multiple elements- Where the elements occur in two or more states- Court with jurisdiction to try. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Offence of conspiracy- Acts or omission of a co- conspirator- When will be ascribed to other conspirators Rationale for. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Offence of conspiracy- What constitutes- Gist of- What prosecution must prove to secure a conviction. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Offence of obtaining by false pretence- What constitutes. 1 CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Offence with multiple elements- Where the elements occur in two or more states- Court with jurisdiction to try. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Offence with multiple elements- Where the elements took place in two or more states- Entry into a state where one of the elements occur- What constitutes. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE- Section 124(2) (b) of the Criminal Code- Purport of. EVIDENCE- Offence of conspiracy- Acts or omission of a co- conspirator- When will be ascribed to other conspirators Rationale for. EVIDENCE- Offence of conspiracy- What constitutes- Gist of- What prosecution must prove to secure a conviction. EVIDENCE- Offence of obtaining by false pretence- What constitutes. JURISDICTION- Offence with multiple elements- Where the elements occur in two or more states-LAW Court with jurisdiction COMPANION to try. STATUTES- Section 124(2) (b) of the Criminal Code- Purport of. -

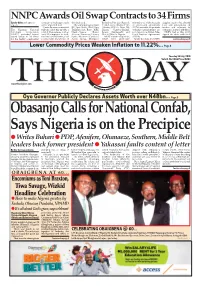

1F35e3e1-Thisday-Jul

NNPC Awards Oil Swap Contracts to 34 Firms Ejiofor Alike with agency contracts to exchange crude the deals said. Barbedos/Petrogas/Rainoil; referred to as offshore crude supplies crude oil to selected reports oil for imported fuel. The winning groups include: UTM/Levene/Matrix/Petra oil processing agreements local and international oil Under the new contract that BP/Aym Shafa; Vitol/Varo; Atlantic; TOTSA; Duke Oil; (OPAs) and crude-for-products traders and refineries in The Nigerian National will take effect this month, a Trafigura/AA Rano; MRS; Sahara; Gunvor/Maikifi; exchange arrangements, are exchange for petrol and diesel. Petroleum Corporation total of 15 groupings, with at Oando/Cepsa; Bono/ Litasco /Brittania-U; and now known as Direct Sale- NNPC had in May 2017, (NNPC) yesterday issued least 34 companies in total, Akleen/Amazon/Eterna; Mocoh/Mocoh Nigeria. Direct Purchase Agreements signed the deals with local award letters to oil firms received award letters, four Eyrie/Masters/Cassiva/ NNPC’s crude swap deals, (DSDP). for the highly sought-after sources with knowledge of Asean Group; Mercuria/ which were previously Under the deals, the NNPC Continued on page 8 Lower Commodity Prices Weaken Inflation to 11.22%... Page 8 Tuesday 16 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8863 Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO Oyo Governor Publicly Declares Assets Worth over N48bn... Page 9 Obasanjo Calls for National Confab, Says Nigeria is on the Precipice Writes Buhari PDP, Afenifere, Ohanaeze, Southern, Middle Belt leaders back former president Yakassai faults content of letter By Our Correspondents plunging into an abyss of before Nigeria witnesses the varied reactions from some aligned with Obasanjo’s Forum (ACF), Alhaji Tanko insecurity. -

Chief Rex Kola Olawoye V. 1. Engineer Raphael Jimoh

362 Nigerian Weekly Law Reports 23 September 2013 CHIEF REX KOLA OLAWOYE V. 1. ENGINEER RAPHAEL JIMOH (Vice Chairman, Ifelodun Local Government Council of Kwara State) 2. HON. ALHAJI LATEEF A. QUADRI 3. FASEYI O. OLUYEMI SUPREME COURT OF NIGERIA SC. 90/2005 MUHAMMAD SAIFULLAHI MUNTAKA-COOMASSIE, J.S.C. (Presided JOHN AFOLABI FABIYI, J.S.C. NWALI SYLVESTER NGWUTA, J.S.C. OLUKAYODE ARIWOOLA, J.S.C. (Read the Leading Judgment) MUSA DATTIJO MUHAMMAD, J.S.C. FRIDAY, 12TH APRIL 2013 ACTION - Joinder of parties - Necessary party - Non- joinder of a necessary party - Effect - Whether fatal. ACTION - Joinder of parties - Non-joinder or misjoinder of a necessary party - How determined - Effect - Principles guiding. ACTION - Parties to an action - Necessary party - Who is - Necessary parties - Who are. ACTION - Parties to an action - Plaintiff - Right of to choose person or persons he wishes to sue. ACTION - Parties to an action - Who are. [2013] 13 NWLR Olawoye v. Jimoh 363 COURT - Order of court - Order against a person who was not a party to proceedings - Validity and patency of. JUDGMENT AND ORDER - Order of court - Order against a person who was not a party to proceedings - Validity and potency of. PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - Parties to an action - Necessary party – Who is - Necessary parties - Who are. PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - Joinder of parties - Necessary party - Non-joinder of a necessary party - Effect - Whether fatal. PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE - Joinder of parties - Non-joinder or misjoinder of a necessary party - How determined - Effect - Principles guiding. WORDS AND PHRASES - “Necessary party” - “Necessary parties” - Meaning of. WORDS AND PHRASES - “Parties to an action” - Who are. -

Election Results Transmitted to Server, INEC Ad-Hoc Officers Tell Tribunal

Mele Kyari: NNPC will Raise Bar on Transparency Promises to fix nation’s refineries by 2023 To unveil new roadmap in couple of weeks Kasim Sumaina in Abuja Corporation (NNPC) with Kyari, who promised to He spoke in Abuja at a join me to unveil the NNPC short and long term growth a pledge to continuously make the nation’s refineries valedictory ceremony for his Roadmap towards global objectives of the corporation as Mallam Mele Kyari assumed entrench transparency, functional by 2023, said in a predecessor, Dr. Maikanti Baru. excellence and the roadmap we transit to a national energy duty yesterday as the Group accountability and performance few weeks he would unveil Kyari said: “In the next will guide our aspirations to champion.” Managing Director of the excellence across all the oil his agenda for the nation’s couple of weeks, the COOs achieve sustained outstanding Nigerian National Petroleum corporation’s operations. oil sector. (chief operating officers) will performance to meet the Continued on page 8 Osinbajo: Ethno-Religious Suspicion Nigeria’s Greatest Problem... Page 6 Tuesday 9 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8856. Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO EIGHTY HEART CHEERS... L-R: Chief Bisi Akande, Ambassador Babagana Kingibe, Dr. Obafemi Hamzat, Governor Abdullahi Ganduje, a guest, Governor Dapo Abiodun, Senate President Ahmed Lawan, Vice President Yemi Osinbajo, Oba Rilwan Akiolu, another guest, Mrs Derinola Osoba, Chief Olusegun Osoba, a guest and Senator Bola Tinubu, during the presentation of Osoba’s book: Battlelines: Adventures into Journalism and Politics, to mark his 80th birthday in Lagos...yesterday KOLA OLASUPO Election Results Transmitted to Server, INEC Ad-hoc Officers Tell Tribunal Atiku, PDP call witnesses, tender more documents Alex Enumah in Abuja Two of the six witnesses called by the petitioners said Some witnesses in the hearing they served as ad-hoc staff of of the petition filed by the INEC and testified that results Peoples Democratic Party were transmitted electronically (PDP) and its presidential to the commission’s server. -

In the Panel of the National Judicial Council Holden at Abuja

IN THE PANEL OF THE NATIONAL JUDICIAL COUNCIL HOLDEN AT ABUJA IN THE PETITIONS OF ALLEGED FINANCIAL IMPROPRIETY, INFIDELITY TO THE CONSTITUION AND OTHER ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES RELATED LAWS BY THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES COMMISSION AGAINST HON. JUSTICE WALTER SAMUEL NKANU ONNOGHEN, GCON WRITTEN ADDRESS SUBMITTED BY THE COUNSEL TO THE RESPONDENT Respondent’s Counsel R.A. Lawal-Rabana, SAN Okon Nkanu Efut, SAN J.U.K. Igwe, SAN George Ibrahim,Esq Victoria Agi, Esq Orji Ude Ekumankama, Esq Opeyemi Origunloye, Esq Temitayo Fiki, Esq For Service On Counsel For the Petitioner Economic and Financial Crimes Commission Rotimi Oyedepo, Esq [email protected] 1 IN THE PANEL OF THE NATIONAL JUDICIAL COUNCIL HOLDEN AT ABUJA IN THE PETITIONS OF ALLEGED FINANCIAL IMPROPRIETY, INFIDELITY TO THE CONSTITUION AND OTHER ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES RELATED LAWS BY THE ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES COMMISSION AGAINST HON. JUSTICE WALTER SAMUEL NKANU ONNOGHEN, GCON 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission sent two (2) petitions to the Chairman, National Judicial Council through the office of the Chief Justice of Nigeria against The Hon. Justice Walter Samuel Nkanu Onnoghen, GCON, Chief Justice of Nigeria. 1.2 The first petition is dated 4th February, 2019 vide reference EFCC/EC/GC/31/2253 while the second petition is dated 5th March 2019 vide reference EFCC/EC/CJN/05/59. 1.3 The petition was forwarded to the Hon. Chief Justice of Nigeria by the National Judicial Council vide a memo dated 11th February 2019 reference NJC/F1/SC.3/1/570 following the 17th Emergency meeting of the Council held the same 11th February 2019. -

![Nigerian Banking Law Reports [1997]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6425/nigerian-banking-law-reports-1997-1396425.webp)

Nigerian Banking Law Reports [1997]

NIGERIAN BANKING LAW REPORTS [1997] VOLUME 7 (PART II) To be cited as: [1997] 7 N.B.L.R. (PART II) Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation 2009 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation Plot 447/448 Airport Road Central Business District P.M.B. 284, Garki Abuja, Federal Capital Territory [FCT] Nigeria Tel: +23495237715-6, +523696740-44 Members of the LexisNexis Group worldwide South Africa LexisNexis DURBAN 215 North Ridge Road, Morningside, 4001 JOHANNESBURG First Floor, 25 Fredman Drive, Sandton, 2196 CAPE TOWN Ground Floor, Waterford House, 2 Ring Road, Century City, 7441 www.lexisnexis.co.za Australia LexisNexis, CHATSWOOD, New South Wales Austria LexisNexis Verlag ARD Orac GmbH & Co KG, VIENNA Benelux LexisNexis Benelux, AMSTERDAM China LexisNexis, BEIJING Canada LexisNexis Butterworths, MARKHAM, Ontario France LexisNexis SA, PARIS Germany LexisNexis Germany, MÜNSTER Hong Kong LexisNexis, HONG KONG Hungary HVG-Orac, BUDAPEST India LexisNexis Butterworths Wadhwa Nagpur, NEW DELHI Ireland Butterworths (Ireland) Ltd, DUBLIN Italy Giuffrè Editore, MILAN Japan LexisNexis, TOKYO Korea LexisNexis, SEOUL Malaysia LexisNexis, KUALA LUMPUR New Zealand LexisNexis, WELLINGTON Poland LexisNexis Poland, WARSAW Singapore LexisNexis, SINGAPORE United Kingdom LexisNexis Butterworths, LONDON USA LexisNexis, DAYTON, Ohio © 2009 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation, published by LexisNexis (Pty) Ltd under licence ISSN 1595-1030 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying and recording, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature. -

INOGHA MFA & ORS V. MFA INONGHA

INOGHA MFA & ORS v. MFA INONGHA IN THE SUPREME COURT OF NIGERIA ON FRIDAY, THE 17TH DAY OF JANUARY, 2014 SUIT NO:305/2006 ELECTRONIC CITATION: LER[2014]SC.305/2006 OTHER CITATIONS: [___] CORAM BETWEEN WALTER SAMUEL JUSTICE OF THE 1. INOGHA MFA APPELLANTS NKANU ONNOGHEN SUPREME COURT MUHAMMAD SAIFULLAH JUSTICE OF THE 2. NDOMA MFA SUPREME COURT MUNTAKA-COOMASSIE JUSTICE OF THE AND SUPREME COURT SULEIMAN GALADIMA JUSTICE OF THE MFA INONGHA RESPONDENT SUPREME COURT NWALI SYLVESTER JUSTICE OF THE NGWUTA SUPREME COURT KUDIRAT MOTONIMORI JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OLATOKUNBO KEKERE- JUSTICE OF THE EKUN SUPREME COURT JUDGMENT NWALI SYLVESTER NGWUTA, J.S.C. (Delivering the Leading Judgment): In the High Court of Justice of Cross River State, sitting at Ikom, the Respondent, as plaintiff, claimed against the appellants as defendants as follows: "1. A declaration that he is owner and entitled to possession of the plot of land and house thereon and situate along Ikom/Calabar Road. 2. A mandatory order compelling the defendants to hand over all relevant documents in relation to plaintiff's plot. 3. A perpetual injunction restraining the defendants, their agents, privies, servants from further interfering with right of the plaintiff to the aforesaid plot and house." The matter was finally determined in the Calabar Judicial Division of the Cross River State High Court by the learned trial Judge, Edem, J., before whom trial opened in the Ikom Judicial Division. In his judgment delivered on 5th March, 2002 the learned trial Judge granted the PAGE| 2 three reliefs claimed by the Respondent as plaintiff. -

DR. OLUBUKOLA ABUBAKAR SARAKI V. FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA SUPREME COURT of NIGERIA SC.852/2015 MAHMUD MOHAMMED. C.J.N. (Presi

DR. OLUBUKOLA ABUBAKAR SARAKI V. FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA SUPREME COURT OF NIGERIA SC.852/2015 MAHMUD MOHAMMED. C.J.N. (Presided) WALTER SAMUEL NKAKU ONNOGHEN. J.S.C. (Read the Leading Judgment) IBRAHIM TANKO MUHAMMAD, J.S.C. NWAL1 SYLVESTER NGWUTA. J.S.C. KUDIRAT MOTONMORI OLATOKUNBO KEKERE-EKUN. J.S.C. CHIMA CENTUS NWEZE, J.S.C. AM1RU SANUSI, J.S.C. FRIDAY. 5TH FEBRUARY 2016 ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Code of conduct for public officers -Purpose of. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Jurisdiction of - Nature of. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Powers of -Whether can compel appearance of person before it by bench warrant. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Quorum of - Whether provided for in 1999 Constitution (as amended) or Code of Conduct Bureau and Tribunal Act - Sections 318(4), 1999 Constitution and 28 Interpretation Act considered. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Sanctions of - Whether purely administrative. ADMINISTRATIVE LAW - Commission or Tribunal of Inquiry -Quorum of - What is - Section 28, Interpretation Act. APPEAL - Brief of argument - Reply brief - Purpose of. APPEAL - Concurrent findings of fact by lower courts - Attitude of Supreme Court thereto - When will interfere therewith - When will not. CODE OF CONDUCT - Code of conduct for public officers -Purpose of. CODE OF CONDUCT - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Existence of - Source of. CODE OF CONDUCT - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Jurisdiction of - Nature of. CODE OF CONDUCT - Code of Conduct Tribunal - Powers of-Whether can compel appearance of person before it by bench warrant. CODE OF CONDUCT- Code of Conduct Tribunal - Proceedings of - Rules governing - Application of Administration of Criminal Justice Act. -

Nigerian Banking Law Reports

NIGERIAN BANKING LAW REPORTS [2004 – 2006] VOLUME 13 PART III To be cited as: [2004 – 2006] 13 N.B.L.R. PART III Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation Plot 447/448 Airport Road Central Business District P.M.B. 284, Garki Abuja, Federal Capital Territory [FCT] Nigeria Tel: +23495237715–6, +523696740–44 Members of the LexisNexis Group worldwide South Africa LexisNexis (Pty) Ltd DURBAN 215 Peter Mokaba Road (North Ridge Road), Morningside, Durban, 4001 JOHANNESBURG Building No. 9, Harrowdene Office Park, 124 Western Service Road, Woodmead, 2191 CAPE TOWN Office Floor 2, North Lobby, Boulevard Place, Heron Close, Century City, 7441 www.lexisnexis.co.za Australia LexisNexis, CHATSWOOD, New South Wales Austria LexisNexis Verlag ARD Orac, VIENNA Benelux LexisNexis Benelux, AMSTERDAM Canada LexisNexis Canada, MARKHAM, Ontario China LexisNexis, BEIJING France LexisNexis, PARIS Germany LexisNexis Germany, MÜNSTER Hong Kong LexisNexis, HONG KONG India LexisNexis, NEW DELHI Italy Giuffrè Editore, MILAN Japan LexisNexis, TOKYO Korea LexisNexis, SEOUL Malaysia LexisNexis, KUALA LUMPUR New Zealand LexisNexis, WELLINGTON Poland LexisNexis Poland, WARSAW Singapore LexisNexis, SINGAPORE United Kingdom LexisNexis, LONDON USA LexisNexis, DAYTON, Ohio © 2013 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation, published by LexisNexis (Pty) Ltd under licence ISSN 1595–1030 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying and recording, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature. -

Volume 10 Part 2

NIGERIAN BANKING LAW REPORTS [2000 – 2001] VOLUME 10 (PART II) To be cited as: [2000 – 2001] 10 N.B.L.R. (PART II) Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation Plot 447/448 Airport Road Central Business District P.M.B. 284, Garki Abuja, Federal Capital Territory [FCT] Nigeria Tel: +23495237715-6, +523696740-44 Members of the LexisNexis Group worldwide South Africa LexisNexis Durban 215 Peter Mokaba Road (North Ridge Road), Morningside, 4001 Johannesburg First Floor, 25 Fredman Drive, Sandton, 2196 Cape Town Office Floor 2, North Lobby, Boulevard Place, Heron Close, Century City, 7114 www.lexisnexis.co.za Australia LexisNexis, CHATSWOOD, New South Wales Austria LexisNexis Verlag ARD Orac GmbH & Co KG, VIENNA Benelux LexisNexis Benelux, AMSTERDAM China LexisNexis, BEIJING Canada LexisNexis Butterworths, MARKHAM, Ontario France LexisNexis SA, PARIS Germany LexisNexis Germany, MÜNSTER Hong Kong LexisNexis, HONG KONG Hungary HVG-Orac, BUDAPEST India LexisNexis Butterworths Wadhwa Nagpur, NEW DELHI Ireland Butterworths (Ireland) Ltd, DUBLIN Italy Giuffrè Editore, MILAN Japan LexisNexis, TOKYO Korea LexisNexis, SEOUL Malaysia LexisNexis, KUALA LUMPUR New Zealand LexisNexis, WELLINGTON Poland LexisNexis Poland, WARSAW Singapore LexisNexis, SINGAPORE United Kingdom LexisNexis Butterworths, LONDON USA LexisNexis, DAYTON, Ohio © 2009 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation, published by LexisNexis (Pty) Ltd under licence ISSN 1595-1030 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying and recording, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature.