May 1, 2017 Price $8.99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jon Rick Curriculum Vitae

JON RICK CURRICULUM VITAE 204 Hill St. Department of Philosophy Chapel Hill, NC 27514 UNC Chapel Hill Phone: 917-301-6659 CB # 3125 Email: [email protected] 240 East Cameron St. Chapel Hill, NC 27599 Dept. Phone: 919-962-2280 Dept. Fax: 919-843-3929 EMPLOYMENT The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Visiting Assistant Professor, 2009-10 EDUCATION Ph.D. Philosophy, Columbia University, 2009 M.Phil. Philosophy, Columbia University, 2005 M.A. Philosophy, Columbia University, 2003 B.A. Philosophy, Columbia University, 2001 Senior Honors Thesis: ‘Might There Be Normative Internal Reasons?’ Advisor: Akeel Bilgrami, 2001 Columbia University’s Oxford/Cambridge Scholars Program, St. Peter’s College, Oxford, 1999-2000. AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Moral, Social, and Political Philosophy, History of Modern Moral Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Practical Reason & Value Theory, Metaethics, Philosophy of Economics FELLOWSHIPS AND AWARDS MELLON AMERICAN COUNCIL OF LEARNED SOCIETIES DISSERTATION COMPLETION FELLOWSHIP, 2008-2009, National dissertation write-up fellowship WHITING FELLOWSHIP, Columbia University, 2008-2009 (declined to accept Mellon/ACLS) Dissertation write-up fellowship awarded to 11 (on average) Columbia students in the humanities WOLSTEIN FELLOWSHIP, Columbia University, 2007-2008 Awarded for scholarship in value theory TOBY STROBER MEMORIAL FELLOWSHIP, Columbia University, 2005-2006 Awarded for scholarship in moral or scientific theory JONATHAN LEIBERSON MEMORIAL PRIZE, Columbia University, 2004 Awarded for the best essay showing the applicability of moral or scientific theory to a social or historical issue. Page 1. Curriculum Vitae: Jon Rick PUBLICATIONS “Hume’s and Smith’s Partial Sympathies and Impartial Stances,” Journal of Scottish Philosophy, vol. 5.2 (October 2007). PRESENTATIONS Invited Panelist for a public discussion sponsored by the UNC Economics Club entitled, “What Defines Fairness? Theories of Justice and Inequality,” Chapel Hill, NC, December 2009. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

BRBL 2016-2017 Annual Report.Pdf

BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report Cover: Yale undergraduate ensemble Low Strung welcomed guests to a reception celebrating the Beinecke’s reopening. contributorS The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library acknowledges the following for their assistance in creating and compiling the content in this annual report. Articles written by, or adapted from, Phoenix Alexander, Matthew Beacom, Mike Cummings, Michael Morand, and Eve Neiger, with editorial guidance from Lesley Baier Statistics compiled by Matthew Beacom, Moira Fitzgerald, Sandra Stein, and the staff of Technical Services, Access Services, and Administration Photographs by the Beinecke Digital Studio, Tyler Flynn Dorholt, Carl Kaufman, Mariah Kreutter, Mara Lavitt, Lotta Studios, Michael Marsland, Michael Morand, and Alex Zhang Design by Rebecca Martz, Office of the University Printer Copyright ©2018 by Yale University facebook.com/beinecke @beineckelibrary twitter.com/BeineckeLibrary beinecke.library.yale.edu SubScribe to library newS messages.yale.edu/subscribe 3 BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 3, 2016–17 Annual Report 4 From the Director 5 Beinecke Reopens Prepared for the Future Recent Acquisitions Highlighted Depth and Breadth of Beinecke Collections Destined to Be Known: African American Arts and Letters Celebrated on 75th Anniversary of James Weldon Johnson Collection Gather Out of Star-Dust Showcased Harlem Renaissance Creators Happiness Exhibited Gardens in the Archives, with Bird-Watching Nearby 10 344 Winchester Avenue and Technical Services Two Years into Technical -

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer's Modest Proposals This Piece Comes to You Compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poli

BROADWAY BOUND: Mezer’s Modest Proposals This piece comes to you compliments of ACREL Fellow Steve Mezer of Becker & Poliakoff who has a front row view of Broadway for several reasons. He is on the Board of the Straz Performing Arts Center in Tampa that invests in and presents Broadway shows. He is also a theater aficionado who spends his free time in NYC with his wife Karen bingeing on Broadway and Off Broadway musicals. Broadway theater is a unique American cultural experience. Other cities have vibrant theater scenes, but no other American venue offers Broadway’s range of options. I recommend that you come a day early and stay a date later for our Fall meeting in New York and take in a couple of Broadway shows. I grew up 90 miles outside of New York City; Broadway was and remains a family staple. I can neither sing nor dance, but I have a great appreciation for musical theater. So here are my recommendations: Musicals: 2016 was one of Broadway’s most successful years as it presented many original works and attracted unprecedented attention with Hamilton and its record breaking (secondary market) ticket prices. October is a transition month, an exciting time to see a new Broadway show. Holiday Inn, an Irving Berlin musical, begins previews September 1, and opens on October 6 at Studio 54. Jim (played by Bryce Pinkham) leaves his farm in Connecticut and meets Linda (Laura Lee Gayer) a school teacher brimming with talent. Together they turn a farmhouse into an inn with dazzling performances to celebrate each holiday. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Capitalism and The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Capitalism and the Production of Realtime: Improvised Music in Post-unification Berlin A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Music by Philip Emmanuel Skaller Committee in Charge: Professor Jann Pasler, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Anthony Davis 2009 The Thesis of Philip Emmanuel Skaller is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii DEDICATION I would like to thank my chair Jann Pasler for all her caring and knowledgeable feedback, for all the personal and emotional support that she has given me over the past year, and for being a constant source of positive inspiration and critical thinking! Jann, you are truly the best chair and mentor that a student could ever hope for. Thank you! I would also like to thank a sordid collection of cohorts in my program. Jeff Kaiser, who partook in countless discussions and gave me consistent insight into improvised music. Matt McGarvey, who told me what theoretical works I should read (or gave me many a contrite synopsis of books that I was thinking of reading). And Ben Power, who gave me readings and perspectives from the field of ethnomusicology and (tried) to make sure that I used my terminology clearly and consciously and also (tried) to help me avoid overstating or overgeneralizing my thesis. Lastly, I would like to dedicate this work to my partner Linda Williams, who quite literally convinced me not to abandon the project, and who's understanding of the contemporary zeitgeist, patient discussions, critical feedback, and related areas of research are what made this thesis ultimately realizable. -

Department of Philosophy California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 3801 W

ALEX MADVA CURRICULUM VITAE CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Philosophy California State Polytechnic University, Pomona 3801 W. Temple Blvd. Pomona, CA 91768 Office: (909) 869-3847 Office Location: Building 1, Room 329 [email protected], [email protected] http://alexmadva.com AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Philosophy of Mind and Cognitive Science, Philosophy of Race and Feminism, Applied Ethics (esp. Prejudice and Discrimination) AREAS OF COMPETENCE Philosophy of Social Science, Phenomenology and Existentialism, Social and Political Philosophy, Introduction to Philosophy through Classic Western Literature EMPLOYMENT 2016- California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Assistant Professor 2015-2016 California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Visiting Assistant Professor 2014-2015 Vassar College Visiting Assistant Professor 2012-2014 University of California, Berkeley Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow EDUCATION 2004-2012 Columbia University (New York) 2012 (Oct) PhD, Philosophy Dissertation: The Hidden Mechanisms of Prejudice: Implicit Bias & Interpersonal Fluency (Committee: Christia Mercer (adviser), Patricia Kitcher, Taylor Carman, Tamar Szabó Gendler, Virginia Valian) 2009 MPhil, Philosophy 2005 MA, Philosophy 2000-2004 Tufts University (Medford, MA) 2004 BA, Philosophy and English, Summa Cum Laude Phi Beta Kappa Madva 1 PUBLICATIONS “Biased against Debiasing: On the Role of (Institutionally Sponsored) Self-Transformation in the Struggle against Prejudice,” (Forthcoming), Ergo. “Stereotypes, Conceptual Centrality and Gender Bias: An Empirical Investigation” (Forthcoming), with Guillermo Del Pinal and Kevin Reuter, Ratio. “A Plea for Anti-Anti-Individualism: How Oversimple Psychology Misleads Social Policy,” (November 2016), Ergo. “Stereotypes, Prejudice, and the Taxonomy of the Implicit Social Mind,” (Forthcoming), co-authored with Michael Brownstein (Assistant Professor, John Jay College of Criminal Justice), Noûs. “Why Implicit Attitudes Are (Probably) not Beliefs,” (2016), Synthese, 193, 2659–2684. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER Position: A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy Address: Department of Philosophy 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006 Address (September 2017-July 2018) Institut d’études avancées 17, quai d’Anjou 75004 Paris France Telephone: 609-258-4307 (voice) 609-258-1502 (FAX) 609-258-4289 (Departmental office) Email: [email protected] Erdös number: 16 EDUCATIONAL RECORD Harvard University, 1967-1975 A.B. in Philosophy, 197l A.M. in Philosophy, 1974 Ph.D. in Philosophy, 1975 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Princeton University 2002- Professor of Philosophy and Associated Faculty, Program in the History of Science 2005-12 Chair, Department of Philosophy 2008-09 Old Dominion Professor 2009- Associated Faculty, Department of Politics 2009-16 Stuart Professor of Philosophy Garber -2- 2016- A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy University of Chicago 1995-2002 Lawrence Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy, the Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science, the Morris Fishbein Center for Study of History of Science and Medicine and the College 1986-2002 Professor 1982-86 Associate Professor (with tenure) 1975-82 Assistant Professor 1998-2002 Chairman, Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science (formerly Conceptual Foundations of Science) 2001 Acting Chairman, Department of Philosophy 1995-98 Associate Provost for Education and Research 1994-95 Chairman, Conceptual Foundations of Science 1987-94 Chairman, Department of Philosophy Harvard College 1972-75 Teaching Assistant and Tutor University of Minnesota, Spring 1979, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University, 1980-1981, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Princeton University 1982-1983 Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1985-1986, Member École Normale Supérieure (Lettres) (Lyon, France), November 2000, Professeur invitée. -

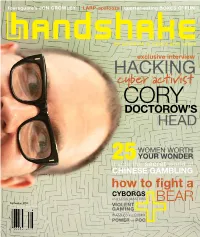

HACKING Cyber Activist CORY DOCTOROW’S HEAD

foursquare’s JON CROWLEY | LARP-apalooza | quarter-eating BOXES O’ FUN the guidebook to modern geek culture exclusive interview HACKING cyber activist CORY DOCTOROW’S HEAD WOMEN WORTH 25 YOUR WONDER inside the secret world of CHINESE GAMBLING how to fight a CYBORGS and LEGO MASTERS BEAR September 2010 VIOLENT US $5.95 | Canada $7.95 GAMING PUZZLES and COMIX POWER of POO SEPT 2010 • PREMIERE ISSUE • handshakemag.com 64 71 78 85 64 71 78 85 CORY DOCTOROW WONDER WOMEN PAI GOW STICK JOCKEYS The co-editor of BoingBoing Jane McGonigal aims to save The casino game attracts a Somewhere between historical takes on commercial Goliaths the world with gaming. Jill following among superstitious reenactment and live action role- with blogs, embraces fatherhood, Thompson captivates comic cults Chinese gamblers but playing, the men and women of and remembers Alice in with Wonder Woman. Summer overwhelms newcomers. Ragnarok turn a Pennsylvania Wonderland. Glau attends casting calls for sci- Singaporean sports gambler Ali campground into an epic fi shows. These 25 gals rule with Kasim went to Foxwoods Casino battlefield. keyboards, comics, and brains. to take on the veterans. WOMAN: YO MOSTRO HANDSHAKE SEPT 2010 3 93 52 44 xx 100 58 36 ANORAK DEPARTMENTS ETC. essay level up beaker duct tape / page 100 .Com-patibility / page 31 Supreme Censorship / page 41 Saved by Shit / page 52 Ponzi Scheme Why finding love online is Violent video games head to Dependence on foreign oil, Bernie made off like a bandit. more common – and more the Supreme Court in October. global warming, and agricultural Now you can too. -

2019 Catalog

2019 CATALOG Point Blank Music School 1215 Bates Avenue Los Angeles, CA 90029 (323) 282-7660 www.pointblanklosangeles.com This Catalog is effective from January 1 through December 31, 2019. Revised: November 20, 2019 Page 1 of 68 TABLE OF CONTENTS MISSION 4 OBJECTIVES 4 GENERAL INFORMATION 5 HISTORY AND OWNERSHIP 5 FACILITIES, EQUIPMENT, AND STUDIOS 5 HOURS 6 CLASS SCHEDULE 6 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2019 6 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020 6 HOLIDAYS 7 APPROVALS 7 ADMISSIONS POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 8 POLICY 8 PROCEDURE 8 PROOF OF GRADUATION 8 ABILITY-TO-BENEFIT 8 NON-DISCRIMINATION 10 INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS AND ENGLISH LANGUAGE SERVICES 10 TRANSFER OF CREDIT 10 NOTICE CONCERNING TRANSFERABILITY OF CREDITS AND CREDENTIALS EARNED AT OUR INSTITUTION 10 ARTICULATION AGREEMENTS 10 PROGRAMS (RESIDENTIAL) 11 Music Production & Sound Design Master Diploma 13 Music Production & Sound Design Advanced Diploma 14 Music Production & Sound Design Diploma 15 Music Production Certificate 16 DJ/Producer Certificate 17 DJ/Producer Award 18 Complete DJ Award 19 Music Production & Composition Award 20 Sound Design & Mixing Award 21 Mixing & Mastering Award 22 Singing Award 23 Essential DJ Skills 24 Music Production 25 Music Composition 26 Sound Design 27 Art of Mixing 28 Audio Mastering 29 Creative Production & Remix 30 Music Business 31 Native Instruments Maschine 32 Singing 33 Advanced Singing 34 Weekend DJ 35 Ableton Production Weekend 36 Ableton Performance Weekend 37 Maschine Weekend 38 COURSE DESCRIPTIONS (RESIDENTIAL) 39 PROGRAMS (ONLINE) 42 Audio Mastering (Online) -

Hebden Bridge Picture House

Films start approx 30 mins after the programme start time stated below. Live Arts/special events actual start time is shown. MAY HEBDEN BRIDGE Mon 1 The Sense of an Ending (15) at 7.45pm TICKETS & CONTACT DETAILS Tues 2 The Sense of an Ending (15) at 7.45pm Weds 3 The Sense of an Ending (15) at 7.45pm Films (no advance booking) PICTURE HOUSE Thurs 4 The Sense of an Ending (15) at 10.30am We operate a cash only box office and do not accept card payments. Graduation (15) at 7.45pm There is no telephone booking facility. Fri 5 The Lost City of Z (15) at 7.45pm Adult £7 Sat 6 Molly Monster (U) at 1.30pm Senior - Over 60 £6 Friends Present: The Long Good Friday (18) at 4.30pm AT A GLANCE A AT Personal Shopper* (15) at 7.45pm Child & Young Adult (age 3-25) £5 Sun 7 Molly Monster (U) at 1.30pm & The Lost City of Z (15) at 4.30pm Passport to Leisure Card Holder £6 The Handmaiden (18) at 7.30pm Full Time Student £5 Mon 8 The Lost City of Z (15) at 7.45pm Tues 9 I am Not Your Negro (12A) at 7.45pm Family Matinee Ticket (everybody) £5 Weds 10 The Handmaiden (18) at 7.30pm Elevenses & Parent and Baby (everybody) £6 Thurs 11 Personal Shopper* (15) at 10.30am Under 3s Free NT Live: Obsession (15) at 7pm (Doors 6pm) Picture This Members enjoy £1 off all of the above prices Fri 12 Their Finest* (12A) at 7.45pm except Family Matinee Tickets Sat 13 Power Rangers (12A) at 1.00pm YSFF Presents The Lodger with Live Harp Score (U) at 4.30pm Live Arts (advance booking recommended)* Their Finest* (12A) at 7.45pm Adult £15 Sun 14 Power Rangers (12A) at 1.00pm