Diptera: Syrphidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osservazioni Sulla Presenza Di Eristalinus (Eristalodes) Taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) (Diptera, Syrphidae) in Piemonte (Italia) E Nel Canton Ticino (Svizzera)

Quaderni del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Ferrara - Vol. 5 - 2017 - pp. 69-71 ISSN 2283-6918 Osservazioni sulla presenza di Eristalinus (Eristalodes) taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) (Diptera, Syrphidae) in Piemonte (Italia) e nel Canton Ticino (Svizzera) MORENO Dutto Già Consulente in Entomologia Sanitaria e Urbana, Servizio Igiene e Sanità Pubblica, Dipartimento di Prevenzione ASL CN1 - E-mail: [email protected] LARA Maistrello Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia - Via G. Amendola 2 - 42122 Reggio-Emilia (Italy) Riassunto Nel presente contributo gli autori confermano la presenza di Eristalinus (Eristalodes) taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) in alcune località del Piemonte centro-meridionale (ovest Italia) e in una località nel Canton Ticino (Svizzera meridionale). I ritrovamenti oggetto del presente contributo rappresentano ritrovamenti occasionali avvenuti prevalentemente in contesti industriali all’interno di pozzetti di scarico delle acque di lavorazione, confermando l’attitudine della specie a svilupparsi a carico di melme organiche di varia natura. Ulteriori indagini potrebbero rilevare una presenza maggiormente diffusa della specie nel nord-ovest d’Italia. Parole Chiave: Eristalinus taeniops, industrie, espansione della specie, melme, miasi. Abstract Remarks on the presence of Eristalinus (Eristalodes) taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) (Diptera, Syrphidae) in Piedmont (Italy) and Canton Ticino (Switzerland). In this paper, the authors confirm the presence of Eristalinus (Eristalodes) taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) in some areas of south-central Piedmont (western Italy) and in a locality in Canton Ticino (southern Switzerland). The present contribution reports on occasional findings detected primarily in industrial contexts within the wells of the process water discharge, confirming the ability of this species to grow in organic sludge of various nature. -

Hoverfly Visitors to the Flowers of Caltha in the Far East Region of Russia

Egyptian Journal of Biology, 2009, Vol. 11, pp 71-83 Printed in Egypt. Egyptian British Biological Society (EBB Soc) ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The potential for using flower-visiting insects for assessing site quality: hoverfly visitors to the flowers of Caltha in the Far East region of Russia Valeri Mutin 1*, Francis Gilbert 2 & Denis Gritzkevich 3 1 Department of Biology, Amurskii Humanitarian-Pedagogical State University, Komsomolsk-na-Amure, Khabarovsky Krai, 681000 Russia 2 School of Biology, University Park, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK. 3 Department of Ecology, Komsomolsk-na-Amure State Technical University, Komsomolsk-na-Amure, Khabarovsky Krai, 681013 Russia Abstract Hoverfly (Diptera: Syrphidae) assemblages visiting Caltha palustris in 12 sites in the Far East were analysed using partitioning of Simpson diversity and Canonical Coordinates Analysis (CCA). 154 species of hoverfly were recorded as visitors to Caltha, an extraordinarily high species richness. The main environmental gradient affecting syrphid communities identified by CCA was human disturbance and variables correlated with it. CCA is proposed as the first step in a method of site assessment. Keywords: Syrphidae, site assessment for conservation, multivariate analysis Introduction It is widely agreed amongst practising ecologists that a reliable quantitative measure of habitat quality is badly needed, both for short-term decision making and for long-term monitoring. Many planning and conservation decisions are taken on the basis of very sketchy qualitative information about how valuable any particular habitat is for wildlife; in addition, managers of nature reserves need quantitative tools for monitoring changes in quality. Insects are very useful for rapid quantitative surveys because they can be easily sampled, are numerous enough to provide good estimates of abundance and community structure, and have varied life histories which respond to different elements of the habitat. -

Hoverfly Newsletter No

Dipterists Forum Hoverfly Newsletter Number 48 Spring 2010 ISSN 1358-5029 I am grateful to everyone who submitted articles and photographs for this issue in a timely manner. The closing date more or less coincided with the publication of the second volume of the new Swedish hoverfly book. Nigel Jones, who had already submitted his review of volume 1, rapidly provided a further one for the second volume. In order to avoid delay I have kept the reviews separate rather than attempting to merge them. Articles and illustrations (including colour images) for the next newsletter are always welcome. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 49 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2010 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email:[email protected], to reach me by 20 May 2010. Please note the earlier than usual date which has been changed to fit in with the new bulletin closing dates. although we have not been able to attain the levels Hoverfly Recording Scheme reached in the 1980s. update December 2009 There have been a few notable changes as some of the old Stuart Ball guard such as Eileen Thorpe and Austin Brackenbury 255 Eastfield Road, Peterborough, PE1 4BH, [email protected] have reduced their activity and a number of newcomers Roger Morris have arrived. For example, there is now much more active 7 Vine Street, Stamford, Lincolnshire, PE9 1QE, recording in Shropshire (Nigel Jones), Northamptonshire [email protected] (John Showers), Worcestershire (Harry Green et al.) and This has been quite a remarkable year for a variety of Bedfordshire (John O’Sullivan). -

Hoverfly Newsletter 67

Dipterists Forum Hoverfly Newsletter Number 67 Spring 2020 ISSN 1358-5029 . On 21 January 2020 I shall be attending a lecture at the University of Gloucester by Adam Hart entitled “The Insect Apocalypse” the subject of which will of course be one that matters to all of us. Spreading awareness of the jeopardy that insects are now facing can only be a good thing, as is the excellent number of articles that, despite this situation, readers have submitted for inclusion in this newsletter. The editorial of Hoverfly Newsletter No. 66 covered two subjects that are followed up in the current issue. One of these was the diminishing UK participation in the international Syrphidae symposia in recent years, but I am pleased to say that Jon Heal, who attended the most recent one, has addressed this matter below. Also the publication of two new illustrated hoverfly guides, from the Netherlands and Canada, were announced. Both are reviewed by Roger Morris in this newsletter. The Dutch book has already proved its value in my local area, by providing the confirmation that we now have Xanthogramma stackelbergi in Gloucestershire (taken at Pope’s Hill in June by John Phillips). Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 68 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2020 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email:[email protected], to reach me by 20 June 2020. The hoverfly illustrated at the top right of this page is a male Leucozona laternaria. -

Ad Hoc Referees Committee for This Issue Thomas Dirnböck

COMITATO DI REVISIONE PER QUESTO NUMERO – Ad hoc referees committee for this issue Thomas Dirnböck Umweltbundesamt GmbH Studien & Beratung II, Spittelauer Lände 5, 1090 Wien, Austria Marco Kovac Slovenian Forestry Institute, Vecna pot 2, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenija Susanna Nocentini Università degli Studi di Firenze, DISTAF, Via S. Bonaventura 13, 50145 Firenze Ralf Ohlemueller Department of Biology, University of York, PO Box 373, York YO10 5YW, UK Sandro Pignatti Orto Botanico di Roma, Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, L.go Cristina di Svezia, 24, 00165 Roma Stergios Pirintsos Department of Biology, University of Crete, P.O.Box 2208, 71409 Heraklion, Greece Matthias Plattner Hintermann & Weber AG, Oeko-Logische Beratung Planung Forschung, Hauptstrasse 52, CH-4153 Reinach Basel Arne Pommerening School of Agricultural & Forest Sciences, University of Wales, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 2UW, DU/ UK Roberto Scotti Università degli Studi di Sassari, DESA, Nuoro branch, Via C. Colombo 1, 08100 Nuoro Franz Starlinger Forstliche Bundesversuchsanstalt Wien, A 1131 Vienna, Austria Silvia Stofer Eidgenössische Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft – WSL, Zürcherstrasse 111, CH-8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland Norman Woodley Systematic Entomology Lab-USDA , c/o Smithsonian Institution NHB-168 , O Box 37012 Washington, DC 20013-7012 CURATORI DI QUESTO NUMERO – Editors Marco Ferretti, Bruno Petriccione, Gianfranco Fabbio, Filippo Bussotti EDITORE – Publisher C.R.A. - Istituto Sperimentale per la Selvicoltura Viale Santa Margherita, 80 – 52100 Arezzo Tel.. ++39 0575 353021; Fax. ++39 0575 353490; E-mail:[email protected] Volume 30, Supplemento 2 - 2006 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS C.R.A.A - ISTITUTO N SPERIMENTALE N A PER LA LSELVICOLTURA I (in alphabetic order) Allegrini, M. C. -

Diptera: Syrphidae), Based on Integrative Taxonomy and Aegean Palaeogeography

Contributions to Zoology, 87 (4) 197-225 (2018) Disentangling a cryptic species complex and defining new species within the Eumerus minotaurus group (Diptera: Syrphidae), based on integrative taxonomy and Aegean palaeogeography Antonia Chroni1,4,5, Ana Grković2, Jelena Ačanski3, Ante Vujić2, Snežana Radenković2, Nevena Veličković2, Mihajla Djan2, Theodora Petanidou1 1 University of the Aegean, Department of Geography, University Hill, 81100, Mytilene, Greece 2 University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology and Ecology, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000, Novi Sad, Serbia 3 Laboratory for Biosystems Research, BioSense Institute – Research Institute for Information Technologies in Biosystems, University of Novi Sad, Dr. Zorana Đinđića 1, 21000, Novi Sad, Serbia 4 Institute for Genomics and Evolutionary Medicine; Department of Biology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA 5 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Aegean, DNA sequences, hoverflies, mid- Discussion ............................................................................. 211 Aegean Trench, wing geometric morphometry Taxonomic and molecular implications ...........................212 Mitochondrial dating, biogeographic history and divergence time estimates ................................................213 Abstract Acknowledgments .................................................................215 References .............................................................................215 This study provides an overview of the Eumerus minotaurus -

HOVERFLY NEWSLETTER Dipterists

HOVERFLY NUMBER 41 NEWSLETTER SPRING 2006 Dipterists Forum ISSN 1358-5029 As a new season begins, no doubt we are all hoping for a more productive recording year than we have had in the last three or so. Despite the frustration of recent seasons it is clear that national and international study of hoverflies is in good health, as witnessed by the success of the Leiden symposium and the Recording Scheme’s report (though the conundrum of the decline in UK records of difficult species is mystifying). New readers may wonder why the list of literature references from page 15 onwards covers publications for the year 2000 only. The reason for this is that for several issues nobody was available to compile these lists. Roger Morris kindly agreed to take on this task and to catch up for the missing years. Each newsletter for the present will include a list covering one complete year of the backlog, and since there are two newsletters per year the backlog will gradually be eliminated. Once again I thank all contributors and I welcome articles for future newsletters; these may be sent as email attachments, typed hard copy, manuscript or even dictated by phone, if you wish. Please do not forget the “Interesting Recent Records” feature, which is rather sparse in this issue. Copy for Hoverfly Newsletter No. 42 (which is expected to be issued with the Autumn 2006 Dipterists Forum Bulletin) should be sent to me: David Iliff, Green Willows, Station Road, Woodmancote, Cheltenham, Glos, GL52 9HN, (telephone 01242 674398), email: [email protected], to reach me by 20 June 2006. -

Diptera) Türleri Üzerinde Faunistik Çalışmalar1

BİTKİ KORUMA BÜLTENİ 2008, 48(4): 35-49 Kayseri ili Syrphidae (Diptera) türleri üzerinde faunistik çalışmalar1 Neslihan BAYRAK2 Rüstem HAYAT2 SUMMARY Faunistic studies on the species of Syrphidae (Diptera) in Kayseri province In this study, totally 2776 specimens belonging to the family Syrphidae (Diptera) were collected and evaluated in Kayseri province between May and August in the years of 2004 and 2005. Totally, 26 species belonging to the Syphidae family have been determined. Of these species, Eumerus sogdianus Stackelberg is new record for the Turkish fauna. Cheilosia proxima (Zetterstedt), Chrysotoxum octomaculatum Curtis, Eristalinus taeniops (Wiedemann), Eumerus sogdianus Stackelberg, Neoascia podogrica (Fabricius), Paragus albifrons (Fallén), Paragus quadrifasciatus Meigen, Pipizella maculipennis (Meigen) and Sphaerophoria turkmenica Bankowska were also recorded from Kayseri province for the first time. Episyrphus balteatus (De Geer, 1776), Eristalinus aeneus (Scopoli), Eristalis arbustorum (Linnaeus, 1758), Eristalis tenax (Linnaeus), Eupeodes corollae (Fabricius, 1794), Sphaerophoria scripta (Linnaeus) and Syritta pipiens (Linnaeus) are abundant and widespread species in the research area. Key words: Diptera, Syrphidae, new record, fauna, Kayseri, Turkey ÖZET Kayseri ilinden toplanan Syrphidae (Diptera) türlerinin değerlendirildiği bu çalışmada, 2004-2005 yıllarının Mayıs-Ağustos ayları arasında, toplam 2776 birey toplanmıştır. Araştırma bölgesinde, Syrphidae familyasına ait toplam 26 tür belirlenmiştir. Bu türlerden, Eumerus -

International Conference Integrated Control in Citrus Fruit Crops

IOBC / WPRS Working Group „Integrated Control in Citrus Fruit Crops“ International Conference on Integrated Control in Citrus Fruit Crops Proceedings of the meeting at Catania, Italy 5 – 7 November 2007 Edited by: Ferran García-Marí IOBC wprs Bulletin Bulletin OILB srop Vol. 38, 2008 The content of the contributions is in the responsibility of the authors The IOBC/WPRS Bulletin is published by the International Organization for Biological and Integrated Control of Noxious Animals and Plants, West Palearctic Regional Section (IOBC/WPRS) Le Bulletin OILB/SROP est publié par l‘Organisation Internationale de Lutte Biologique et Intégrée contre les Animaux et les Plantes Nuisibles, section Regionale Ouest Paléarctique (OILB/SROP) Copyright: IOBC/WPRS 2008 The Publication Commission of the IOBC/WPRS: Horst Bathon Luc Tirry Julius Kuehn Institute (JKI), Federal University of Gent Research Centre for Cultivated Plants Laboratory of Agrozoology Institute for Biological Control Department of Crop Protection Heinrichstr. 243 Coupure Links 653 D-64287 Darmstadt (Germany) B-9000 Gent (Belgium) Tel +49 6151 407-225, Fax +49 6151 407-290 Tel +32-9-2646152, Fax +32-9-2646239 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Address General Secretariat: Dr. Philippe C. Nicot INRA – Unité de Pathologie Végétale Domaine St Maurice - B.P. 94 F-84143 Montfavet Cedex (France) ISBN 978-92-9067-212-8 http://www.iobc-wprs.org Organizing Committee of the International Conference on Integrated Control in Citrus Fruit Crops Catania, Italy 5 – 7 November, 2007 Gaetano Siscaro1 Lucia Zappalà1 Giovanna Tropea Garzia1 Gaetana Mazzeo1 Pompeo Suma1 Carmelo Rapisarda1 Agatino Russo1 Giuseppe Cocuzza1 Ernesto Raciti2 Filadelfo Conti2 Giancarlo Perrotta2 1Dipartimento di Scienze e tecnologie Fitosanitarie Università degli Studi di Catania 2Regione Siciliana Assessorato Agricoltura e Foreste Servizi alla Sviluppo Integrated Control in Citrus Fruit Crops IOBC/wprs Bulletin Vol. -

Cheilosia Praecox and C. Psilophthalma, Two Phytophagous Hoverflies Selected As Potential Biological Control Agents of Hawkweeds (Hieracium Spp.) in New Zealand

680 Session 8 abstracts Proceedings of the X International Symposium on Biological Control of Weeds 4-14 July 1999, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA Neal R. Spencer [ed.]. (2000) phytophagous insects, acting as physical and/or chemical barriers. However, during the evaluation of the foliage feeder (G. boliviana) as an agent for biocontrol of Tropical Soda Apple (Solanum viarum), it was found that the presence of trichomes is a requirement for the plant to be a suitable host. The tarsal claws of G. boliviana larvae are broadly joined to the tarsus and a hook arises from the external side, giving the claw a depressed “c” shape. In order to walk, the trichomes are grasped with the “c” shaped claws and the body is pulled forward. The TSA leaf surface studied under Environmental Scanning Electronic Microscope (ESEM) reveals the presence of five types of trichomes: simple trichomes, simple articulated trichomes, stellate trichomes, glandular trichomes type A, and glandu- lar trichomes type B. The response of neonate larvae to 20 species of Solanaceae plants was analyzed. In some species the lack or the presence of low densities of trichomes does not allow the insects to walk. The movements of the larvae are uncoordinated and even a light draft shakes them off the leaf surface (e.g. Solanum capsicoides). In other species the larvae can walk but they do not feed, probably due to the presence of deterrents, absence of phagostimulants or both (e.g. tomato). Finally, there are species where the high densi- ty of stellate trichomes form an intricate web that acts as a physical barrier that prevents or makes difficult for first instars to reach the leaf surface (e.g. -

Adult Behaviour in Two Species of Cerioicine Flies, Primoerioides Petri (Hervé-Bazin) and Ceriana Japonica (Shiraki) (Diptera S

1 Adult behaviour in two species of cerioidine flies, Primocerioides petri (Hervé-Bazin) and Ceriana japonica (Shiraki) (Diptera Syrphidae) Toshihide ICHIKAWA & Kenji ŌHARA [Abstract, captions of figs all in English] Introduction Most adult Diptera belonging to the Syrphidae are known to be diurnal pollinators which fly to the flowers of various seed plants and feed on nectar and pollen (1, 2, 3) Many different species have black-and-yellow or black-and-orange stripes and are thought to be simulating female adult Apoidea, which are the most important pollinators and have poisonous stings and similar body stripes (4, 5, 6). A tribe of the Syrphidae, Cerioidini, which we study in this paper, has body stripes similar to none of the Apoidea, but instead simulate Eumenidae or Polistinae, both belonging to the Vespoidea, which are generally called hunter wasps. The Cerioidini includes five genera (Ceriana Rafinesque 1815, Monoceromyia Shannon 1925, Polybiomyia Shannon 1925, Sphiximorpha Rondani 1850 and Primocerioides Shannon 1927) and 197 recorded species worldwide, but for only 19 of which are the life-style and development times known (7). In Japan three species of the Cerioidini are known: recent records of the capture of adult insects show that they occur in Honshū, Shikoku and Kyūshū. Observations of adult Monoceromyia pleuralis (Coquillett) are relatively frequent so it became clear that they visit Quercus acutissima and Ulmus, which exude tree-sap from May to September (8, 9, 10, 11). The lifestyle and life history of the other two species, Primocerioides petri (Hervè-Bazin) and Ceriana japonica (Shiraki), are not known, and so accidental encounters remain the only possibility. -

Britain's Hoverflies

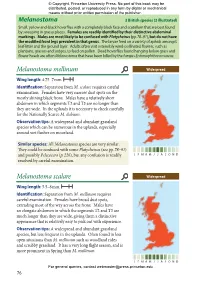

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Melanostoma 3 British species (2 illustrated) Small, yellow-and-black hoverflies with a completely black face and scutellum that are best found by sweeping in grassy places . Females are readily identified by their distinctive abdominal markings . Males are most likely to be confused with Platycheirus (pp. 78–91), but do not have the modified front legs prevalent in that genus . The larvae feed on a variety of aphids amongst leaf-litter and the ground layer . Adults often visit ostensibly wind-pollinated flowers, such as plantains, grasses and sedges, to feed on pollen . Dead hoverflies found hanging below grass and flower heads are often Melanostoma that have been killed by the fungus Entomophthora muscae . Widespread Melanostoma mellinum Wing length: 4·75–7 mm Identification:Separation from M. scalare requires careful examination. Females have very narrow dust spots on the mostly shining black frons. Males have a relatively short abdomen in which segments T2 and T3 are no longer than they are wide. In the uplands it is necessary to check carefully for the Nationally Scarce M. dubium. Observation tips: A widespread and abundant grassland species which can be numerous in the uplands, especially around wet flushes on moorland. Similar species: All Melanostoma species are very similar. They could be confused with some Platycheirus (see pp. 78–91) and possibly Pelecocera (p. 226), but any confusion is readily NOSAJJMAMFJ D resolved by careful examination.