Theme and Technique in Steve Erickson's Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

{Download PDF} Goodbye 20Th Century: a Biography of Sonic

GOODBYE 20TH CENTURY: A BIOGRAPHY OF SONIC YOUTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David Browne | 464 pages | 02 Jun 2009 | The Perseus Books Group | 9780306816031 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century - Wikipedia He was also in the alternative rock band Sonic Youth from until their breakup, mainly on bass but occasionally playing guitar. It was the band's first album following the departure of multi-instrumentalist Jim O'Rourke, who had joined as a fifth member in It also completed Sonic Youth's contract with Geffen, which released the band's previous eight records. The discography of American rock band Sonic Youth comprises 15 studio albums, seven extended plays, three compilation albums, seven video releases, 21 singles, 46 music videos, nine releases in the Sonic Youth Recordings series, eight official bootlegs, and contributions to 16 soundtracks and other compilations. It was released in on DGC. The song was dedicated to the band's friend Joe Cole, who was killed by a gunman in The lyrics were written by Thurston Moore. It featured songs from the album Sister. It was released on vinyl in , with a CD release in Apparently, the actual tape of the live recording was sped up to fit vinyl, but was not slowed down again for the CD release. It was the eighth release in the SYR series. It was released on July 28, The album was recorded on July 1, at the Roskilde Festival. The album title is in Danish and means "Other sides of Sonic Youth". For this album, the band sought to expand upon its trademark alternating guitar arrangements and the layered sound of their previous album Daydream Nation The band's songwriting on Goo is more topical than past works, exploring themes of female empowerment and pop culture. -

SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music

Page 1 The San Diego Union-Tribune October 1, 1995 Sunday SST Defies Industry, Defines New Music By Daniel de Vise KNIGHT-RIDDER NEWSPAPERS DATELINE: LOS ALAMITOS, CALIF. Ten years ago, when SST Records spun at the creative center of rock music, founder Greg Ginn was living with six other people in a one-room rehearsal studio. SST music was whipping like a sonic cyclone through every college campus in the country. SST bands criss-crossed the nation, luring young people away from arenas and corporate rock like no other force since the dawn of punk. But Greg Ginn had no shower and no car. He lived on a few thousand dollars a year, and relied on public transportation. "The reality is not only different, it's extremely, shockingly different than what people imagine," Ginn said. "We basically had one place where we rehearsed and lived and worked." SST, based in the Los Angeles suburb of Los Alamitos, is the quintessential in- dependent record label. For 17 years it has existed squarely outside the corporate rock industry, releasing music and spoken-word performances by artists who are not much interested in making money. When an SST band grows restless for earnings or for broader success, it simply leaves the label. Founded in 1978 in Hermosa Beach, Calif., SST Records has arguably produced more great rock bands than any other label of its era. Black Flag, fast, loud and socially aware, was probably the world's first hardcore punk band. Sonic Youth, a blend of white noise and pop, is a contender for best alternative-rock band ever. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/65f2825x Author Young, Mark Thomas Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Sonic Retro-Futures: Musical Nostalgia as Revolution in Post-1960s American Literature, Film and Technoculture A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Thomas Young June 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Steven Gould Axelrod Dr. Tom Lutz Copyright by Mark Thomas Young 2015 The Dissertation of Mark Thomas Young is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As there are many midwives to an “individual” success, I’d like to thank the various mentors, colleagues, organizations, friends, and family members who have supported me through the stages of conception, drafting, revision, and completion of this project. Perhaps the most important influences on my early thinking about this topic came from Paweł Frelik and Larry McCaffery, with whom I shared a rousing desert hike in the foothills of Borrego Springs. After an evening of food, drink, and lively exchange, I had the long-overdue epiphany to channel my training in musical performance more directly into my academic pursuits. The early support, friendship, and collegiality of these two had a tremendously positive effect on the arc of my scholarship; knowing they believed in the project helped me pencil its first sketchy contours—and ultimately see it through to the end. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

I PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM and the POSSIBILITIES

i PRACTICAL MAGIC: MAGICAL REALISM AND THE POSSIBILITIES OF REPRESENTATION IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY FICTION AND FILM by RACHAEL MARIBOHO DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2016 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Wendy B. Faris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Kenneth Roemer Johanna Smith ii ABSTRACT: Practical Magic: Magical Realism And The Possibilities of Representation In Twenty-First Century Fiction And Film Rachael Mariboho, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Wendy B. Faris Reflecting the paradoxical nature of its title, magical realism is a complicated term to define and to apply to works of art. Some writers and critics argue that classifying texts as magical realism essentializes and exoticizes works by marginalized authors from the latter part of the twentieth-century, particularly Latin American and postcolonial writers, while others consider magical realism to be nothing more than a marketing label used by publishers. These criticisms along with conflicting definitions of the term have made classifying contemporary works that employ techniques of magical realism a challenge. My dissertation counters these criticisms by elucidating the value of magical realism as a narrative mode in the twenty-first century and underlining how magical realism has become an appealing means for representing contemporary anxieties in popular culture. To this end, I analyze how the characteristics of magical realism are used in a select group of novels and films in order to demonstrate the continued significance of the genre in modern art. I compare works from Tea Obreht and Haruki Murakami, examine the depiction of adolescent females in young adult literature, and discuss the environmental and apocalyptic anxieties portrayed in the films Beasts of the Southern Wild, Take iii Shelter, and Melancholia. -

'Post-Los Angeles': the Conceptual City in Steve Erickson's

‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles antae, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jun., 2018), 138-153 Proposed Creative Commons Copyright Notices Authors who publish with this journal agree to the following terms: a. Authors retain copyright and grant the journal right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License that allows others to share the work with an acknowledgement of the work's authorship and initial publication in this journal. b. Authors are permitted and encouraged to post their work online (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) prior to and during the submission process, as it can lead to productive exchanges, as well as earlier and greater citation of published work (See The Effect of Open Access). antae (ISSN 2523-2126) is an international refereed postgraduate journal aimed at exploring current issues and debates within English Studies, with a particular interest in literature, criticism and their various contemporary interfaces. Set up in 2013 by postgraduate students in the Department of English at the University of Malta, it welcomes submissions situated across the interdisciplinary spaces provided by diverse forms and expressions within narrative, poetry, theatre, literary theory, cultural criticism, media studies, digital cultures, philosophy and language studies. Creative writing and book reviews are also encouraged submissions. 138 ‘Post-Los Angeles’: The Conceptual City in Steve Erickson’s Amnesiascope Liam Randles University of Liverpool Erickson’s Conceptual Settings A striking hallmark of Steve Erickson’s fiction—that is, the author’s conceptualisation of setting in order to highlight an environment’s transformative qualities—can be traced from a dual position of personal experience and literary influence. -

The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk

arts Article New Spaces for Old Motifs? The Virtual Worlds of Japanese Cyberpunk Denis Taillandier College of International Relations, Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan; aelfi[email protected] Received: 3 July 2018; Accepted: 2 October 2018; Published: 5 October 2018 Abstract: North-American cyberpunk’s recurrent use of high-tech Japan as “the default setting for the future,” has generated a Japonism reframed in technological terms. While the renewed representations of techno-Orientalism have received scholarly attention, little has been said about literary Japanese science fiction. This paper attempts to discuss the transnational construction of Japanese cyberpunk through Masaki Goro’s¯ Venus City (V¯ınasu Shiti, 1992) and Tobi Hirotaka’s Angels of the Forsaken Garden series (Haien no tenshi, 2002–). Elaborating on Tatsumi’s concept of synchronicity, it focuses on the intertextual dynamics that underlie the shaping of those texts to shed light on Japanese cyberpunk’s (dis)connections to techno-Orientalism as well as on the relationships between literary works, virtual worlds and reality. Keywords: Japanese science fiction; cyberpunk; techno-Orientalism; Masaki Goro;¯ Tobi Hirotaka; virtual worlds; intertextuality 1. Introduction: Cyberpunk and Techno-Orientalism While the inversion is not a very original one, looking into Japanese cyberpunk in a transnational context first calls for a brief dive into cyberpunk Japan. Anglo-American pioneers of the genre, quite evidently William Gibson, but also Pat Cadigan or Bruce Sterling, have extensively used high-tech, hyper-consumerist Japan as a motif or a setting for their works, so that Japan became in the mid 1980s the very exemplification of the future, or to borrow Gibson’s (2001, p. -

REMEMBER THIS SONG? a 2003 Musical Quiz Manus: Claes Nordenskiöld Producent: Claes Nordenskiöld Sändningsdatum: 19/11, 2003 Längd: 14’51

Over to You 2003/2004 Remember This Song? Programnr:31495ra5 REMEMBER THIS SONG? A 2003 Musical Quiz Manus: Claes Nordenskiöld Producent: Claes Nordenskiöld Sändningsdatum: 19/11, 2003 Längd: 14’51 Music: Eminem “Lose Yourself ” Claes Nordenskiöld: Welcome to Remember This Song? – the yearly program that gives you a chance to remember a few of the hits of the past year – A 2003 Musical Quiz. What you heard in the opening was of course Eminem in “Lose Yourself ” from the soundtrack to the movie “8 Mile”. Now, whatever kind of music you like, whether it’s hip-hop, heavy metal, rock or pop, there’ll hopefully be something for you in this program – because there’s so much good music out there. You need a piece of paper and a pencil. I’m looking for a name with 11 letters, which make up the answer. Just write the numbers 1 to 11 on the left-hand side of your paper. And as always, I will play parts of several songs. Each part is a clue to the answer. The clues may be the title of a song, the name of a group or a singer, and so on. You may not be able to answer every single question, but you’ll still have a chance to get the final answer, which I’ll give, at the end of the show. So, let’s get started with the clue for number 3. The members of Outlandish have different ethnic backgrounds – Morocco, Pakistan and Honduras. But the band really comes from Denmark. For number 3, I’m looking for the title of their first super-hit. -

Marching Band Music Library 2019

MARCHING BAND SUGGESTED PLAYLISTS & MUSIC LIBRARY SUGGESTED PLAYLISTS FOR POPULAR EVENTS SESSION OPENER/CLOSER SPORTING EVENT THEME Can’t Stop the Feeling Another One Bites the Dust Celebration Eye of the Tiger Happy Get Ready for This Party Rock Anthem Hey Song Uptown Funk NFL Theme YMCA Seven Nation Army The Final Countdown We Will Rock You/We Are the Champions Zombie Nation AWARD CEREMONIES COCKTAIL PARTIES All I Do is Win 24K Magic Gonna Fly Now (Theme from Rocky) Crazy in Love I Got You (I Feel Good) Get Lucky I Gotta Feeling Hit Me Baby One More Time Sweet Caroline Old Town Road Macho Man Tequila Theme from Rocky U Can’t Touch This Wannabe PATRIOTIC EVENTS WEDDING/ENGAGEMENT America the Beautiful Every Little Thing She Does is Magic God Bless America Gimme Some Lovin’ Living in America I Saw Her Standing There Star Spangled Banner She’s Some Kind of Wonderful Stars & Stripes Forever So Happy Together The Washington Post March The Power of Love Yankee Doodle MARCHING BAND FULL MUSIC LIBRARY *Custom Arrangements Additional Rates Apply A-G H-R S-Z 24K Magic Happy School’ Out Africa Hawaii Five-O September All About that Bass Hip to be Square Shake, Rattle & Roll All I Do is Win Hit Me Baby One More Time She’s Some Kind of Wonderful All the Single Ladies Hit Me with Your Best Shot Seven Nation Army All the Small Things I Got You (I Feel Good) So Happy Together America the Beautiful I Gotta Feeling Spooky Another One Bites the Dust I Love Rock n’ Roll Star Spangled Banner Ants Marching I Saw Her Standing There Stars & Stripes Forever -

College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2011-2012 Student Newspapers 10-31-2011 College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5" (2011). 2011-2012. 15. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012/15 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2011-2012 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ----- - -- -- ~-- ----. -- - - - GOBER 31 2011 VOllJiVlE XCI . ISSUE5 NEW LONDON. CONNEOK:UT Bieber Fever Strikes Again HEATHER HOLMES Biebs the pass because "Mistle- sian to sit down and listen to his 2009. In the course of two years, and will release his forthcom- Christmas album is that Bieber STAFF WRITER toe" is seriously catchy. music in earnest. This, I now re- the now 17-year-old released his ing album, Under the Mistletoe released his first single from Under the Mistletoe, aptly titled Unlike many of Bieber's big- Before this week, 1 had never alize, was a pretty gigantic mis- Iirst EP, My World (platinum in (which will likely go platinum), "Mistletoe," in mid-October. gest hits, it's the verses rather listened to Justin Bieber. Of take. I'm currently making up the U.S.), his first full-length al- on November 1. than the chorus on "Mistletoe" course, I had heard his biggest for lost time. -

Band Song-List

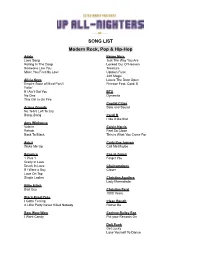

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat.