Timman's Titans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dvoretsky Lessons 48

The Instructor The Effects of Replaying I have frequently mentioned, in books and articles, an effective training method: replaying specially selected positions – positions which cannot be “resolved” from beginning to end, so there is really no sense in trying. Instead, players must find, in succession, a series of correct decisions independently (or nearly independently) of each other. In the majority of such exercises, play continues for a minimum of ten moves, although sometimes longer. After all, a shorter variant could in fact be calculated from beginning to end, which would then abolish it as a playing exercise. But The there are sometimes exceptions. The brilliant attack from the following game, which remained hidden in the Instructor annotations, and which is now offered for your consideration, has for some reason never become widely known, although its basic ideas were demonstrated Mark Dvoretsky in Mikhail Botvinnik’s annotations from his book 1941 Match-Tournament. But even those who are familiar with Botvinnik’s analysis will be none the worse for it – for they too will see sharp new variations. Botvinnik - Bondarevsky Leningrad/Moscow 1941 So – you have White. Try to find each move in turn, taking Black’s replies from the following text. Or you might play out this fragment against a friend: he will also find it a problem requiring deep insight into the position. 39.Ne2xd4! In combination with White’s next move, this is a rather obvious exchange: in this way, White gets the opportunity to speculate on the pin along the a1-h8 diagonal. In the game, Botvinnik played the much weaker 39.Ng3?, and after 39...Qe6! 40.Re2 Be3, he ought to have been dead lost: White has neither his pawn, nor any sort of compensation for it. -

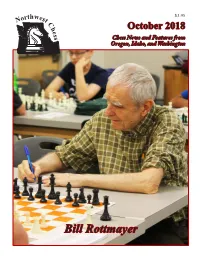

Bill Rottmayer on the Front Cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the Oldest Participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open

$3.95 orthwes N t C h October 2018 e s s Chess News and Features from Oregon, Idaho, and Washington Bill Rottmayer On the front cover: Northwest Chess Bill Rottmayer, the oldest participant in the Spokane Falls October 2018, Volume 72-10 Issue 849 Open. Bill has participated in most Spokane Chess Club events the last few years. Photo credit: James Stripes. ISSN Publication 0146-6941 Published monthly by the Northwest Chess Board. On the back cover: POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Office of Record: Northwest Chess c/o Orlov Chess Academy 4174 148th Ave NE, Dustin Herker at the Las Vegas International Festival where Building I, Suite M, Redmond, WA 98052-5164. he won first place U1000. Photo credit: Nancy Keller. Periodicals Postage Paid at Seattle, WA USPS periodicals postage permit number (0422-390) Chesstoons: NWC Staff Chess cartoons drawn by local artist Brian Berger, Editor: Jeffrey Roland, of West Linn, Oregon. [email protected] Games Editor: Ralph Dubisch, [email protected] Publisher: Duane Polich, Submissions [email protected] Submissions of games (PGN format is preferable for games), Business Manager: Eric Holcomb, stories, photos, art, and other original chess-related content [email protected] are encouraged! Multiple submissions are acceptable; please indicate if material is non-exclusive. All submissions are Board Representatives subject to editing or revision. Send via U.S. Mail to: David Yoshinaga, Josh Sinanan, Jeffrey Roland, NWC Editor Jeffrey Roland, Adam Porth, Chouchanik Airapetian, 1514 S. Longmont Ave. Brian Berger, Duane Polich, Alex Machin, Eric Holcomb. Boise, Idaho 83706-3732 or via e-mail to: Entire contents ©2018 by Northwest Chess. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Chess Viewer the Power of XSL Lies in Its Ability to Perform Radical Transformations of the XML Data Source

DEVELOPER'S ZONE SHOP SEARCH Products Demos Stories Solutions Support Download Customers Partners Company Sitemap Chess Viewer The power of XSL lies in its ability to perform radical transformations of the XML data source. This page contains yet another proof for this fact: you can build a chessgame viewer with a stylesheet! The source document is a transcription of a chess game played by Garry Kasparov against a chess supercomputer -- IBM Deep Blue. The game is encoded in a form resembling the well-known Portable Game Notation (PGN) format. The source is very compact: a sample game on this page [DeepBlue.xml] is less than 4 kBytes in size. The stylesheet converts this arid text into a sequence of board diagrams, drawing every intermediate position as a graphical image (a special chess font is used). Applying a 23 kB stylesheet [chess.xsl], we get a 415 kBytes (!) FO stream [DeepBlue.fo]. These numbers give an idea of how deep the transformation is. The final step of the whole procedure consists in converting the result into PDF using XEP. The resulting PDF file [DeepBlue.pdf] is much smaller than the source FO stream -- less than 90 kBytes. (XEP implements PDF compression). We hope XSL fans will enjoy this example; and XSL foes will acknowledge its power! More chess games created by the same stylesheet: Description FO Source PDF PostScript Fischer-Euwe.xml Fischer-Euwe.fo Fischer-Euwe.pdf Fischer-Euwe.ps Robert Fischer - Max Euwe Fischer-Tal.xml Fischer-Tal.fo Fischer-Tal.pdf Fischer-Tal.ps Robert Fischer - Mikhail Tal Kasparov-Karpov.xml Kasparov-Karpov.fo Kasparov-Karpov.pdf Kasparov-Karpov.ps Garry Kasparov - Anatoly Karpov Note: We have used an unabridged chess notation; the original PGN data are even more concise.We know it is possible to process even the short chess notation by XSL, and gladly leave this exercise to volunteers . -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

Grand Prix Proves to Be Right Formula

7.Ng1–f3 0–0 22... e7-e6 A better idea was 7...Bc8-g4, 23.Qg6-h7+ Kg8-f7 CHESS getting rid of the light-squared 24.f5xe6+ Bc8xe6 July 5th 2008 bishop which is hard to find 25.Rh3-h6 Qc7-e5 a good post for. Another 26.Qh7-g6+ Kf7-g8 Michael interesting option was 7...c5-c4, 27.Rf1xf6 Qe5-d4+ trying to create counterplay. 28.Rf6-f2 Adams Even with what feels like 8.0–0 b7-b6 an overwhelming position, Black doesn't sense any danger it is important to maintain and makes some quiet moves, concentration. The rook retreat but he should have paid more forced resignation but the attention to White’s plans. blunder 28.Kg1–h1 Qd4xf6 Grand Prix As we shall see he can quickly 29.Qg6xf6 Rd8-f8 would lead develop a strong initiative on to a roughly level position. the kingside. proves to be 1–0 9.Qd1–e1 Bc8-g4 right formula The worst possible moment The 2nd edition of Secrets of for this move as the knight is Spectacular Chess by Jonathan no longer pinned. 9...Nf6-d7 Levitt and David Friedgood Gawain Jones is the latest in was preferable although, after (Everyman, £14.99) is a slightly a long line of English players 10.f4-f5 there is trouble ahead expanded version of the 1999 who have specialised in for the Black monarch. original, in which they analysed meeting the Sicilian in an the beauty in chess. off-beat manner. He has 10.Nf3-e5 Qd8-c7 The book is especially shared his expertise in his 11.Qe1–h4 Bg4-e6 interesting to players with little first book, Starting Out: 12.Ne5-f3 h7-h6 experience of studies who will Sicilian Grand Prix Attack 12...Be6-c8 13.f4-f5 is no discover many paradoxical (Everyman, £14.99). -

A Game of Queens

Judit Polgar Teaches Chess 3 A Game of Queens by Judit Polgar with invaluable help from Mihail Marin Quality Chess www.qualitychess.co.uk Contents Key to Symbols used 4 Preface 5 1 Kasparov 11 2 Karpov 45 3 Korchnoi 71 4 The Rapid Match with Anand 101 5 Oliver 115 6 Hanna 141 7 The Opening 167 8 The Middlegame 199 9 The Endgame 217 10 Unexpected Moves 273 11 Official Competitions 285 12 Where It All Started 365 Records and Results 382 Name Index 384 Game Index 387 126 A Game of Queens Judit Polgar – Ivan Sokolov have relied, though, on the fact that I had never before faced it in practice. Wijk aan Zee 2005 13.d5 1.e4 e5 2.¤f3 ¤c6 3.¥b5 a6 4.¥a4 ¤f6 It looks logical to block the centre after Black 5.0–0 ¥e7 6.¦e1 b5 7.¥b3 d6 8.c3 0–0 no longer has the freeing ...c7-c6. In the long Ivan has played the Ruy Lopez throughout run, Black will have to re-develop his bishop, his career, so he has had the time to try out most likely with ...¥c8-d7. all kinds of systems: the Berlin Wall and the Marshall Attack, the Open and Bird If White wishes to maintain the tension in the variations, as well as several systems in the centre, the alternatives are 13.¤f1 ¦e8 14.¤g3 closed variations. and 13.b3. Back in 1994 in Madrid, I won my first game against Ivan by somewhat restricting his 13...g6 choice with 9.d4, but by 2005 I used to stick 13...c4 is a typical reaction after d4-d5, but to the main lines. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

Anatoly Karpov INTRODUCTION

FOREWARD In December of 1998 as I was winning the first ever FIDE World Active Championship in Mazatlan Mexico, I noticed I had the same person working the chess wall board for my very difficult final matches versus Viktor Gavrikov and Roman Dzindzichashvili. Imagine my surprise as I was autographing a book, when he asked if I would consider an American second for the upcoming Candidates Quarter-final match with Hjartarson. The idea seemed interesting as more and more matches were taking place in English speaking countries, so I suggested we meet at the end of the event after the closing ceremonies. In checking with my team, we discovered in his youth, Henley had scored impressive wins versus Timman, Seirawan, Ribli, Miles, Short and others, followed by a very long gap. I also found it a good omen that Ron shared the December 5th birthday of my first trainer/mentor and very good friend Semyon Furman who passed in 1978. Throughout the nineties, Ron joined our team for matches with Anand, Timman (2), Yusupov, Gelfand, Kamsky and Kasparov. In “Win Like Karpov” Henley explains in a basic easy to understand level many of the strategies and tactics that brought me success at key moments in my career. I have contributed notes, commentary and photos to several key moments from my “Second Career” in the 1990’s when I achieved my highest ELO - 2780 and regained the FIDE World Championship. GM Henley has done an excellent job of identifying several key opening positions as well as certain types of recurring themes in my Classical Style of middlegame play. -

Floridachess Summer 2019

Summer 2019 GM Olexandr Bortnyk wins the 26th Space Coast Open FCA BOARD OF DIRECTORS [term till] kqrbn Contents KQRBN President Kevin J. Pryor (NE) [2019] Editor Speaks & President’s Message .................................................................... 3 Jacksonville, FL [email protected] FCA’s Membership Growth .......................................................................................... 4 FCA Elections ....................................................................................................................... 4 Vice President Ukrainian Takes Over Space Coast Open by Peter Dyson .................................. 5 Stephen Lampkin (NE) [2019] Port Orange, FL Space Coast Open Brilliancy Prize winners by Javad Maharramzade .............. 5 [email protected] 2019 CFCC Sunshine Open by Steven Vigil ............................................................... 10 by Miguel Ararat ................................................. Secretary Some games from recent events 12 Bryan Tillis (S) [2019] A game from the 26th Space Coast Open ............................................................. 16 West Palm Beach, FL Meet the Candidates .........................................................................................................19 [email protected] 2019 FCA Voting Procedures .......................................................................................19 Treasurer 2019 Queen’s Cup Challenge by Kevin Pryor .............................................................. 20 Scott -

Carlsen, Fischer &

VER LAG DIE WERK STATT GÖTTIN GEN IN FOR MA TION Martin Breutigam Carlsen, Fischer & Co. The World Chess Champions from 1886 until today They were child prodigies and scientists, eccentrics and artists: the players who won the World Chess Championship in the last 130 years. This book portrays all of them: The American genius Bobby Fischer and his Russian opponent Boris Spassky (whose preparation for the “Match of the Century” in 1972 included playing tennis!). The Russian Vasily Smyslov who was not only good at chess but an excellent opera singer at that. And Norwegian poster boy Magnus Carlsen who has been dubbed the “Justin Bieber of chess”. Full of anecdotes and brilliant combinations, this book is a must read for any chess lover! The author Martin Breutigam, born 1965 in Bremen, Germany, is an International Master and a long-time Chess Bundesliga player. He works as a journalist for German newspapers Süddeutsche Zeitung and Tagesspiegel and has published several books and DVDs on chess. Sales points • Large target audience: This book addresses all lovers of chess, beginners as well as advanced players. • It’s the perfect gift for any chess fan. • Increasing popularity of chess in recent years – not least due to Magnus Carlsen. Martin Breutigam Carlsen, Fischer & Co. The World Chess Champions from 1886 until today 208 pages, 13,5 x 21,5 cm, paperback ISBN 978–3–7307–0287–1 Date of publication: October 2016 German retail price: 14,90 “ Rights available: all languages VER LAG DIE WERK STATT · Lotzestraße 22a · 37083 Göttingen · Tel. 0551/7896510 · Fax 78965125 E-Mail: [email protected] · Internet: www.werkstatt-verlag.de Foreign rights manager: Julia Vogt, Tel.