The Effects of the Three-Point Rule in Individual Sports: Evidence from Chess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Players Biel International Chess Festival

2009 Players Biel International Chess Festival Players Boris Gelfand Israel, 41 yo Elo: 2755 World ranking: 9 Date and place of birth: 24.6.1968, in Minsk (Belarus) Lives in: Rishon-le-Zion (Israel) Israel ranking: 1 Best world ranking: 3 (January 1991) In Biel GMT: winner in 1993 (Interzonal) and 2005. Other results: 3rd (1995, 1997, 2001), 4th (2000) Two Decades at the Top of Chess This is not a comeback, since Boris Gelfand never left the chess elite in the last twenty years. However, at the age of 41, the Israeli player has reached a new peak and is experiencing a a third wind. He is back in the world Top-10, officially as number 9 (in fact, a virtual number 5, if one takes into account his latest results that have not yet been recorded). He had not been ranked so high since 2006. Age does not seem to matter for this player who is unanimously appreciated in the field, both for his technical prowess and his personality. In Biel, he will not only be the senior player of the Grandmaster tournament, but also the top ranked and the Festival’s most loyal participant. Since his first appearance in 1993, he has come seven times to Biel; it is precisely at this Festival that he earned one of his greatest victories: in 1993, he finished first in the Interzonal Tournament (which, by then, was the only qualifying competition for the world championship), out of 73 participating grandmasters (including Anand and Kramnik). His victory in Biel against Anand is mentioned in his book, My Most Memorable Games. -

Spieler Alexander Morozevich

2006 Spieler Biel International Chess Festival Spieler Alexander Morozevich Russland Elo: 2731 Geburtsdatum und ‐Ort: 18.7.1977 in Moskau Lebt in: Moskau Nationale Rangliste: 3 Weltrangliste: 9 Beste Platzierung: 4 (2000, 2001, 2004) In Biel GMT: Gewinner 2003 und 2004 Alexander Morozevich ist einer jener Spieler, welche die Geschichte des Bieler Schachfestivals am meisten geprägt haben. Bei beiden Teilnahmen brillierte er und holte sich jeweils unangefochten den Turniersieg, 2003 mit 8 aus 10 und 2004 mit 7.5 Punkten. Anlässlich seiner beiden Besuche erspielte er 11 Siege und 9 Remis, womit er ungeschlagen ist. Biel ist für Alexander Morozevich ein exellentes Pflaster. Der 29jährige Moskowiter Grossmeister treibt seine Gegner oft zur Verzweiflung, indem er wie kein anderer auf dem Schachbrett ein taktisches Feuerwerk zu entzünden vermag. Unter seinesgleichen gilt er als einer der kreativsten und unberechenbarsten Spieler überhaupt. Er wird deshalb bei seinem dritten Gastspiel im Kongresshaus den Hattrick anstreben, was im Grossmeisterturnier bisher nur Anatoly Karpov in den Jahren 1990, 92 und 96 erreicht hat. Als aktuelle Nummer 9 der Weltrangliste (Rang 4 war bisher seine beste Klassierung) wird er der H öchstdotierte in Biel sein. In den letzten Monaten hat Alexander Morozevich hervorragende Leistungen erzielt. Im Herbst 2005 erreichte er an den Weltmeisterschaften in San Luis, Argentinien, den 4. Rang (den Titel holte Veselin Topalov). Im Anschluss war er massgeblich an der Goldmedaille Russlands bei der Mannschaftsweltmeisterschaft in Beer‐Sheva, Israël, beteiligt. Mit Schwarz erkämpfte er sich und seinem Team den entscheidenden Punkt gegen China. Schliesslich gewann er im Frühling 2006 zum 3. Mal in seiner Karriere zusammen mit Anand das prestigeträchtige Amberturnier in Monaco (eine Kombination von Rapid‐ und Blindpartien). -

Joueurs Biel International Chess Festival

2006 Joueurs Biel International Chess Festival Joueurs Alexander Morozevich Russie Elo: 2731 Date et lieu de naissance: 18.7.1977 à Moscou Lieu de résidence: Moscou Classement national: 3 Classement mondial: 9 Meilleur classement mondial: 4 (2000, 2001, 2004) GMT à Bienne: Vainqueur en 2003 et 2004 C’est certainement l’un des joueurs qui a le plus marqué l’histoire du Festival de Bienne. Il y a remporté avec un brio déconcertant les deux tournois des grands maîtres auxquels il a participé. En 2003, avec 8 points sur 10, puis en 2004 avec 7,5 points. En deux visites et vingt parties, Alexander Morozevich a fêté 11 victoires et 9 nuls. Il reste invaincu. Bienne lui sied à merveille. Artiste déroutant pour ses adversaires, le grand maître moscovite (29 ans) n’a pas son pareil pour mettre le feu à l’échiquier. Considéré par ses pairs comme l’un des joueurs les plus créatifs et imprévisibles du circuit mondial, il visera donc la passe de trois au Palais des Congrès (ce que seul Anatoly Karpov est parvenu à accomplir au tournoi des grands maîtres, en 1990, 92 et 96). Actuel numéro 9 mondial (son meilleur classement fut le 4e rang), il sera le mieux cot é de tous à Bienne. Alexander Morozevich a aligné les performances de premier choix ces derniers mois. A l’automne 2005, il a décroché (à San Luis, en Argentine) le 4e rang du championnat du monde individuel (remporté par Veselin Topalov). Dans la foulée, il était l’un des grands artisans de la médaille d’or de la Russie au championnat du monde par équipes (à Beer‐Sheva, Israël). -

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020

World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020 World Stars 2020 ● Tournament Book ® Efstratios Grivas 2020 1 Welcome Letter Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club President Sheikh Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Mualla Dear Participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club and the Organising Committee, I am delighted to welcome all our distinguished participants of the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020! Unfortunately, due to the recent negative and unpleasant reality of the Corona-Virus, we had to cancel our annual live events in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. But we still decided to organise some other events online, like the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship 2020, in cooperation with the prestigious chess platform Internet Chess Club. The Sharjah Cultural & Chess Club was founded on June 1981 with the object of spreading and development of chess as mental and cultural sport across the Sharjah Emirate and in the United Arab Emirates territory in general. As on 2020 we are celebrating the 39th anniversary of our Club I can promise some extra-ordinary events in close cooperation with FIDE, the Asian Chess Federation and the Arab Chess Federation for the coming year 2021, which will mark our 40th anniversary! For the time being we welcome you in our online event and promise that we will do our best to ensure that the World Stars Sharjah Online International Chess Championship -

CHESS TOURNAMENT MARKETING SUPPORT by Purple Tangerine COMMERCIAL SPONSORSHIP & PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES

COMMERCIAL SPONSORSHIP & PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES PRO-BIZ CHALLENGE 2016 Now in it’s 5th year, the Pro-Biz Challenge is the starter event for the London Chess Classic giving business people and their companies the SCHEDULE opportunity of a lifetime: to team up with one of their chess heroes! ACTIVITY VENUES TIMING Pro-Biz Challenge Press Launch Central London Host Partner tbc It brings the best business minds and the world’s leading Grand Masters PR Fund Raising Event Central London Host Partner September together in a fun knockout tournament to raise money for the UK charity, Chess in Schools and Communities (CSC). Businesses can bid to play with Pro-Biz Challenge Final Central London Host Partner December their favourite players and the ones who bid the highest get the chance to team up with a Grand Master. In 2014, the Pro-Biz Challenge included a team featuring rugby legend Sir Clive Woodward, who teamed up with leading British GM Gawain Jones. They fought hard, but after a three-round knockout, the top honours went to Anish Giri and Rajko Vujatovic of Bank of America. The current Champions are: Hikaru Nakamura (USA) and Josip Asik, CEO of Chess Informant. QUICK FACTS TEAMS 8 teams of two – one Company (Amateur Player) and one Grand Master from the London Chess Classic RAPID PLAY The Company Player (Amateur) and Grand Master in each team will take it in turns to make moves in Rapid Play games, FORMAT with each team allowed two one-minute time-outs per game to discuss strategy or perhaps just a killer move PRIZE Bragging Rights and -

London Chess Classic, Round 5

PRESS RELEASE London Chess Classic, Round 5 SUPER FABI GOES BALLISTIC , OTHERS LOSE THEIR FOCUS ... John Saunders reports: The fifth round of the 9th London Chess Classic, played on Wednesday 6 December 2017 at the Olympia Conference Centre, saw US number one Fabiano Caruana forge clear of the field by a point after winning his second game in a row, this time against ex-world champion Vishy Anand. Tournament leader Fabiano Caruana talks to Maurice Ashley in the studio (photo Lennart Ootes) It ’s starting to look like a one-man tournament. Caruana has won two games, the other nine competitors not one between them. We ’ve only just passed the mid-point of the tournament, of course, so it could all go wrong for him yet but it would require a sea change in the pacific nature of the tournament for this to happen. Minds are starting to go back to Fabi ’s wonder tournament, the Sinquefield Cup of 2014 when he scored an incredible 8 ½/10 to finish a Grand Canyon in points ahead of Carlsen, Topalov, Aronian, Vachier-Lagrave and Nakamura. That amounted to a tournament performance rating of 3103 which is so off the scale for these things that it doesn ’t even register on the brain as a feasible Elo number. Only super-computers usually scale those heights. For Fabi to replicate that achievement he would have to win all his remaining games in London. But he won ’t be worrying about the margin of victory so much as finishing first. He needs to keep his mind on his game and I won ’t jinx his tournament any further with more effusive comments. -

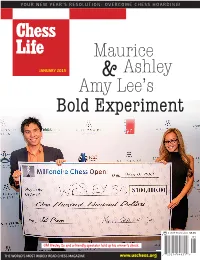

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING!

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING! Maurice JANUARY 2015 & Ashley Amy Lee’s Bold Experiment FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JANUARY A USCF Publication $5.95 01 GM Wesley So and a friendly spectator hold up his winner’s check. 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:28 AM Page 1 SLCC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:50 AM Page 1 The Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis is preparing for another fantastic year! 2015 U.S. Championship 2015 U.S. Women’s Championship 2015 U.S. Junior Closed $10K Saint Louis Open GM/IM Title Norm Invitational 2015 Sinquefi eld Cup $10K Thanksgiving Open www.saintlouischessclub.org 4657 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314) 361–CHESS (2437) | [email protected] NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY: The CCSCSL admits students of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. THE UNEXPECTED COLLISION OF CHESS AND HIP HOP CULTURE 2&72%(5r$35,/2015 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 (314) 367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org Photo © Patrick Lanham Financial assistance for this project With support from the has been provided by the Missouri Regional Arts Commission Arts Council, a state agency. CL_01-2014_masthead_JP_r1_chess life 12/10/2014 10:30 AM Page 2 Chess Life EDITORIAL STAFF Chess Life Editor and Daniel Lucas [email protected] Director of Publications Chess Life Online Editor Jennifer Shahade [email protected] Chess Life for Kids Editor Glenn Petersen [email protected] Senior Art Director Frankie Butler [email protected] Editorial Assistant/Copy Editor Alan Kantor [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jo Anne Fatherly [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jennifer Pearson [email protected] Technical Editor Ron Burnett TLA/Advertising Joan DuBois [email protected] USCF STAFF Executive Director Jean Hoffman ext. -

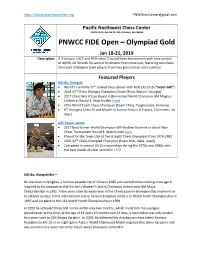

PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold

https://www.pnwchesscenter.org [email protected] Pacific Northwest Chess Center 12020 113th Ave NE #C-200, Kirkland, WA 98034 PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold Jan 18-21, 2019 Description A 3-section, USCF and FIDE rated 7-round Swiss tournament with time control of 40/90, SD 30 with 30-second increment from move one, featuring two Chess Olympiad Champion team players from two generations and countries. Featured Players GM Bu, Xiangzhi • World’s currently 27th ranked chess player with FIDE Elo 2726 (“Super GM”) • 2018 43rd Chess Olympia Champion (Team China, Batumi, Georgia) • 2017 Chess World Cup Round 4 (Eliminated World Champion GM Magnus Carlsen in Round 3. Watch video here) • 2015 World Team Chess Champion (Team China, Tsaghkadzor, Armenia) • 6th Youngest Chess Grand Master in human history (13 years, 10 months, 13 days) GM Tarjan, James • 2017 Beat former World Champion GM Vladimir Kramnik in Isle of Man Chess Tournament Round 3. Watch video here • Played for the Team USA at five straight Chess Olympiads from 1974-1982 • 1976 22nd Chess Olympiad Champion (Team USA, Haifa, Israel) • Competed in several US Championships during the 1970s and 1980s with the best results of clear second in 1978 GM Bu, Xiangzhi Bio – Bu was born in Qingdao, a famous seaside city of China in 1985 and started chess training since age 6, inspired by his compatriot GM Xie Jun’s Women’s World Champion victory over GM Maya Chiburdanidze in 1991. A few years later Bu easily won in the Chinese junior championship and went on to achieve success in the international arena: he won 3rd place in the U12 World Youth Championship in 1997 and 1st place in the U14 World Youth Championship in 1998. -

ICCF Tournament Rules 2008 0. Overview 0.1. the Correspondence

ICCF Tournament Rules 2008 0. Overview The correspondence chess tournaments of the ICCF are divided into: a) Title Tournaments 0.1. b) Promotion Tournaments, c) Cup Tournaments, d) Special Tournaments. Normally the entry fee for each tournament will be decided by Congress. Entry to a tournament will be 0.2 accepted only if it is accompanied by payment of the entry fee to the collection agency designated by the ICCF. Unless explicitly stated otherwise each player plays one game simultaneously against each of the other 0.3 players in the tournament or section; the colour will be decided by lot. 1. Title Tournaments The ICCF Title Tournaments comprise: a) World Correspondence Chess Championships (Individual) b) Ladies World Correspondence Chess Championships (Individual) 1.0.1 c) Correspondence Chess Olympiads (World Championships for National Teams) d) Ladies Correspondence Chess Olympiads (World Championships for Ladies National Teams) All entries for the Title Tournaments must be processed via the Member Federations. Direct entries are allowed only in exceptional cases and the Title Tournaments Commissioner will individually consider these. The World Championships organised by the ICCF comprise Preliminaries, Semi-Finals, Candidates' 1.0.2 Tournament and Final. The Preliminaries, Semi-Finals and Candidates' Tournaments comprise separate sections played normally by 1.0.3 post, by Email and by webserver. The qualifications reached in postal tournaments can be used in Email and webserver tournaments and vice versa. The Preliminaries, Semi-Finals and Candidates' Tournaments are progressive tournaments. New sections of the World Championship Preliminaries, Semi-Finals and Candidates' Tournaments will be started throughout the year, as soon as there is a sufficient number of qualifiers wishing to begin play in the section, using their 1.0.4 preferred method of transmission of moves (i.e. -

Sample Pages

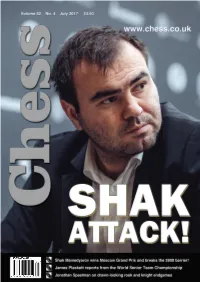

01-01 July Cover_Layout 1 18/06/2017 21:25 Page 1 02-02 NIC advert_Layout 1 18/06/2017 19:54 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/06/2017 20:32 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial.................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcom Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...John Bartholomew....................................................7 We catch up with the IM and CCO of Chessable.com Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Not a Classic .......................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Steve Giddins wasn’t overly taken with the Moscow Grand Prix Subscription Rates: How Good is Your Chess? ..........................................................................11 United Kingdom Daniel King features a game from the in-form Mamedyarov 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Bundesliga Brilliance.....................................................................................14 3 year (36 issues) £125 Matthew Lunn presents two creative gems from the Bundesliga Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Find the Winning Moves .............................................................................18 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Can you do as well as some leading -

Www . Polonia Chess.Pl

Amplico_eng 12/11/07 8:39 Page 1 26th MEMORIAL of STANIS¸AW GAWLIKOWSKI UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE CITY OF WARSAW HANNA GRONKIEWICZ-WALTZ AND THE MARSHAL OF THE MAZOWIECKIE VOIVODESHIP ADAM STRUZIK chess.pl polonia VII AMPLICO AIG LIFE INTERNATIONAL CHESS TOURNEMENT EUROPEAN RAPID CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP www. INTERNATIONAL WARSAW BLITZ CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP WARSAW • 14th–16th December 2007 Amplico_eng 12/11/07 8:39 Page 2 7 th AMPLICO AIG LIFE INTERNATIONAL CHESS TOURNAMENT WARSAW EUROPEAN RAPID CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP 15th-16th DEC 2007 Chess Club Polonia Warsaw, MKS Polonia Warsaw and the Warsaw Foundation for Chess Development are one of the most significant organizers of chess life in Poland and in Europe. The most important achievements of “Polonia Chess”: • Successes of the grandmasters representing Polonia: • 5 times finishing second (1997, 1999, 2001, 2003 and 2005) and once third (2002) in the European Chess Club Cup; • 8 times in a row (1999-2006) team championship of Poland; • our players have won 24 medals in Polish Individual Championships, including 7 gold, 11 silver and 4 bronze medals; • GM Bartlomiej Macieja became European Champion in 2002 (the greatest individual success in the history of Polish chess after the Second World War); • WGM Beata Kadziolka won the bronze medal at the World Championship 2005; • the players of Polonia have had qualified for the World Championships and World Cups: Micha∏ Krasenkow and Bart∏omiej Macieja (six times), Monika Soçko (three times), Robert Kempiƒski and Mateusz Bartel (twice), -

Francuska Odbrana 3 Rubinstein

FRANCUSKA ODBRANA 3 „VARIJANTA DŽOBAVE“ [C10] 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 £c6 RUBINSTEINOVA VARIJANTA [C10] 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 dxe4 4. £xe4 STEINITZOVA VARIJANTA [C11] 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 £f6 4.e5 £fd7 SADRŽAJ Prvi deo. „Varijanta Džobave“ i Rubinsteinova varijanta Poglavlje 1. „Varijanta Džobave“ [C10] 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 £c6 ......................................................................................................... 17 1a 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 £c6 4. £f3 ........................................................................................... 18 No 1. DOMINGUEZ – DŽOBAVA, Tromsö (ol) 2014 ............................................... 18 No 2. LEKO – MOROZEVIČ, Frankfurt 2000 ............................................................... 23 1b 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 £c6 4.e5 .............................................................................................. 26 No 3. GIRI – DŽOBAVA, Hanti-Mansijsk FIDE GP 2015 ....................................... 26 No 4. KARJAKIN – DŽOBAVA, Hanti-Mansijsk FIDE GP 2015 ......................... 29 Poglavlje 2. Rubinsteinova varijanta [C10] 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 dxe4 4. £xe4 ...................................................................................... 31 2a 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 dxe4 4. £xe4 £f6 ............................................................................ 32 No 5. CARUANA – RAPPORT, Wijk aan Zee 2014 ................................................... 32 2c. Fort Knox 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3. £c3 dxe4 4. £xe4 §d7 5. £f3 §c6 ..................................................