HP 35S Scientific Calculator User's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calculating Numerical Roots = = 1.37480222744

#10 in Fundamentals of Applied Math Series Calculating Numerical Roots Richard J. Nelson Introduction – What is a root? Do you recognize this number(1)? 1.41421 35623 73095 04880 16887 24209 69807 85696 71875 37694 80731 76679 73799 07324 78462 10703 88503 87534 32764 15727 35013 84623 09122 97024 92483 60558 50737 21264 41214 97099 93583 14132 22665 92750 55927 55799 95050 11527 82060 57147 01095 59971 60597 02745 34596 86201 47285 17418 64088 91986 09552 32923 04843 08714 32145 08397 62603 62799 52514 07989 68725 33965 46331 80882 96406 20615 25835 Fig. 1 - HP35s √ key. 23950 54745 75028 77599 61729 83557 52203 37531 85701 13543 74603 40849 … If you have had any math classes you have probably run into this number and you should recognize it as the square root of two, . The square root of a number, n, is that value when multiplied by itself equals n. 2 x 2 = 4 and = 2. Calculating the square root of the number is the inverse operation of squaring that number = n. The "√" symbol is called the "radical" symbol or "check mark." MS Word has the radical symbol, √, but we often use it with a line across the top. This is called the "vinculum" circa 12th century. The expression " (2)" is read as "root n", "radical n", or "the square root of n". The vinculum extends over the number to make it inclusive e.g. Most HP calculators have the square root key as a primary key as shown in Fig. 1 because it is used so much. Roots and Powers Numbers may be raised to any power (y, multiplied by itself x times) and the inverse operation, taking the root, may be expressed as shown below. -

Calculating Solutions Powered by HP Learn More

Issue 29, October 2012 Calculating solutions powered by HP These donations will go towards the advancement of education solutions for students worldwide. Learn more Gary Tenzer, a real estate investment banker from Los Angeles, has used HP calculators throughout his career in and outside of the office. Customer corner Richard J. Nelson Learn about what was discussed at the 39th Hewlett-Packard Handheld Conference (HHC) dedicated to HP calculators, held in Nashville, TN on September 22-23, 2012. Read more Palmer Hanson By using previously published data on calculating the digits of Pi, Palmer describes how this data is fit using a power function fit, linear fit and a weighted data power function fit. Check it out Richard J. Nelson Explore nine examples of measuring the current drawn by a calculator--a difficult measurement because of the requirement of inserting a meter into the power supply circuit. Learn more Namir Shammas Learn about the HP models that provide solver support and the scan range method of a multi-root solver. Read more Learn more about current articles and feedback from the latest Solve newsletter including a new One Minute Marvels and HP user community news. Read more Richard J. Nelson What do solutions of third degree equations, electrical impedance, electro-magnetic fields, light beams, and the imaginary unit have in common? Find out in this month's math review series. Explore now Welcome to the twenty-ninth edition of the HP Solve Download the PDF newsletter. Learn calculation concepts, get advice to help you version of articles succeed in the office or the classroom, and be the first to find out about new HP calculating solutions and special offers. -

HP-16C Computer Scientist

I ~4 HEWLETT-PACKARD HP-16C Computer Scientist OWNER S HANDBOOK Us I .III ieSSSSIImini iiiiii «iawl ^37=- (-W) Ris=i(+W) -3 mmn mtrnt mrmi M*m* tmtm i WKtni W4MU WK0013 7W7WW TltflU tWMII MM It'l JBF47Sf2 H7F37W tWHN NOTICE Hewlett-Packard Company makes no express or implied warranty with regard to the keystroke procedures and program material offered or their merchantability or their fitness for any particular purpose. The keystroke procedures and program material are made available solely on an "as is" basis, and the entire risk as to their quality and performance is with the user. Should the keystroke procedures or program material prove defective, the user (and not Hewlett-Packard Company nor any other party) shall bear the entire cost of all necessary correction and all incidental or consequential damages. Hewlett-Packard Company shall not be liable for any incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the furnishing, use, or performance of the keystroke procedures or program material. Thai HEWLETT m^f!M PACKARD HP-16C Computer Scientist Owner's Handbook April 1982 00016-90001 Printed in U.S.A. © Hewlett-Packard Company 1 982 Introduction Welcome to the world of the Hewlett-Packard Computer Scientist! You're in good company with HP—the calculator of choice for astronauts in the space shuttle, climbers on Mt. Everest, yachtsmen in the America's Cup, and engineers, scientists, and students the world over. The HP-16C is a versatile and unique calculator, especially designed for the many professionals and students who work with computers and microprocessors—whether as programmers or designers. -

HP Scientific Calculators Which One Is Right for You?

HP Calculators HP Scientific Calculators Which one is right for you? HP Scientific calculators are equipped with easy-to-use problem solving tools, enhanced capabilities and customized options, plus award-winning HP support. When choosing the right scientific calculator, make sure to purchase the one that best fits your needs. Use the comparison chart below to compare HP scientific calculator models. HP 10s+ HP 300s+ HP 35s Perfect for Students in middle and high school Students in middle and high school University students and technical professionals Key Characteristics User-friendly design, easy-to-read display Sophisticated calculator with easy-to-read Professional performance featuring RPN* and a wide range of algebraic, trigonometric, 4-line display, unit conversions as well mode, keystroke programming, the HP Solve** probability and statistics functions. as algebraic, trigonometric, logarithmic, application as well as algebraic, trigonometric, probability and statistics functions. logarithmic and statistics functions, Calculation Mode(s) Algebraic Algebraic Algebraic and RPN Display Size 2 lines x 12 characters, linear display 4 lines x 15 characters, linear display 2 lines , 14 characters, linear display Built-in Functions 240+ 315+ 100+ Size (L x W x D) 5.79 x 3.04 x 0.59 in 5.79 x 3.04 x 0.59 in 6.22 x 3.23 x 0.72 in Subject Suitability General mathematics, Arithmetic, Algebra, General mathematics, Arithmetic, Algebra, Mathematics geared towards Engineering, Trigonometry, Statistics probability Trigonometry, Statistics, Probability Surveying, Science, Medicine Additional Features Solar power plus a battery backup, decimal/ Table-based statistics data editor, solar 800 storage registers, physical constants, hexadecimal conversions, nine memory power plus a battery backup, integer division, unit conversions, adjustable contrast display, registers, slide-on protective cover. -

Introduction to UIL High School Calculator Applications Contest

Introduction to UIL High School Calculator Applications Contest Andy Zapata Azle High School Andy Zapata Azle ISD – 1974 to present Azle HS – Physics teacher Married – 4 children & 2 grandchildren Co-founded Texas Math and Science Coaches Association (TMSCA) Current president of TMSCA Coached all 4 UIL math & science events + slide rule Current UIL Elem/JH number sense, mathematics and calculator consultant [email protected] The Calculator Applications Contest is exactly what the title of the contest implies. It is not a mathematics contest where proofs of geometry or algebra theorems are worked out; it is not a typing contest where the fastest button pusher always has the superior score. It is a contest where engineering type problems are solved. I am not an engineer, but I know a few people that do engineering work, and the ability to use the calculator as a tool to solve; or least begin the problem solving process is very important. But I will also be the first to tell you that the problem topics covered in these contest papers cover finance problems, navigation problems, exponential and compound growth and decay problem, problems involving probability and problems involving calculus that go beyond the averaging processes that occur when calculus cannot be used. If you have students that are curious and competitive, they like math and they like to solve problems; then here is a great opportunity for them to flourish and learn more about the problem solving process than they would normally learn in the high school math program. In 1982 I moved up from teaching seventh grade math to teaching a few classes of physics and different math classes until there were enough students taking physics so that I could have all my classes be physics classes. -

HP 35S Quick Start Guide English EN F2215-90201 Edition 1 V 4.Book

HP 35s Scientific Calculator Quick Start Guide Edition 1 HP part number: F2215-90201 Legal Notices This manual and any examples contained herein are provided "as is" and are subject to change without notice. Hewlett-Packard Company makes no warranty of any kind with regard to this manual, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement and fitness for a particular purpose. In this regard, HP shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained in the manual. Hewlett-Packard Company shall not be liable for any errors or for incidental or consequential damages in connection with the furnishing, performance, or use of this manual or the examples contained herein. Copyright © 2008 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation of this manual is prohibited without prior written permission of Hewlett-Packard Company, except as allowed under the copyright laws. Hewlett-Packard Company 16399 West Bernardo Drive San Diego, CA 92127-1899 USA Printing History Edition 1, version 4, Copyright December 2008 Table of Contents Welcome to your HP 35s Scientific Calculator ........................ 1 Turning the Calculator On and Off ........................................ 2 Adjusting Display Contrast.................................................... 2 Keyboard ........................................................................... 3 Alpha Keys ......................................................................... 4 Cursor Keys ....................................................................... -

The HP-41C: a Literate Calculator?

System Review The HP-41C: A Literate Calculator? Brian P Hayes Scientific American 415 Madison Ave New York NY 10017 Calculator vs Computer can be full of surprises, often to the frustration of the pro The computer and the programmable calculator seem grammer. to be following paths of convergent evolution. As the one The HP-41C, which was introduced by the Hewlett- is made smaller while the other gains in capability, the Packard Company about a year ago, is among the pro line of demarcation between them becomes more and grammable calculators that lie closest to the computer more arbitrary. For now at least, the programmable borderline. It comes close enough for the jargon of com calculator remains a distinct and lesser species, but it puters to be useful in describing it. At the Corvallis Divi shares many of the attributes of the computer. Moreover, sion of Hewlett-Packard, where the HP-41C is made, the shared attributes are chiefly the ones that make the they refer to the calculator itself as the ''mainframe" and computer an interesting machine. Both devices offer an to its accessory devices as the "peripherals." The intimate acquaintance with the powers and pleasures of calculator comes equipped with four input/output (I/O) algorithms. Both exhibit an enigmatic unpredictability: ports, through which the various elements of the system the response of the machine to any given stimulus is are interconnected. Because the peripherals do some data wholly deterministic, yet the behavior of a large program processing internally, the system might even be said to have "distributed intelligence." When compared with a computer, most programmable calculators have a rich instruction set, but they are defi cient in memory capacity and in facilities for communica tion with the user. -

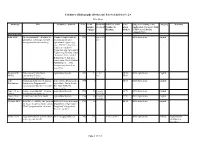

Calculator Bibliography (Books and Selected Articles) V 2.8

Calculator Bibliography (Books and Selected Articles) V 2.8 Felix Gross Author(s) Title Publisher / Journal Year Total Publicati ISBN No. or ID Calc- Subject according to the Language Remarks number on detail Number in ulator Application Category Table of pages Database Models of HP User's Library (August 1983) B100 Agriculture Bahn, H.M. The programmable calculator as Computer applications in 1981 9 pages 205- B100 Agriculture English appropriate technology for farm food production and 213 management decision making agricultural engineering : proc. IFIP TC 5 Working Conference on Food Production and Agricultural Engineering, Havana, Cuba, 26-30 Oct. 1981 / ed. R.E. Kalman and J. Martinez. Amsterdam : North-Holland Publishing Co., c1982. Comput Appl Food Prod Agric Eng Butterworth; Projection of Cattle Herd Agricultural System 1983 13 11:211- HP 25, B100 Agriculture English McNitt Composition Using a 223 HP 67 Programmable Calculator Eads; Controlling Suspended Sediment United States Department of 1985 8 HP 41 B100 Agriculture English Boolootioan Samplers by Programmable Agriculture, Forest Service, Calculator and Interface Circuitry Res. Note PSW-376 Berkeley, CA France; Neal, Using a programmable calculator Agricultural System 1982 13 9, pages TI 59 B100 Agriculture English Pollotti for rationing pregnant ewes 267-279 France; Neal; A dairy herd cash flow model Agricultural System 1982 14 8, pages TI 59 B100 Agriculture English Marsden 129-142 Gardiner, H.G: Auto Sheep : A Budgeting program Bulletin Western Australian 1981 10 - HP 41 B100 Agriculture English for sheep enterprises for use on the Department of Agriculture HP41C programmable calculator Rangeland Management Branch ; no 3022 Heller; Tatzl Programmierbare Taschenrechner BLV Verlagsgesellschaft 1982 156 3-405-12670-3 ? B100 Agriculture German Programmable in der Agrarwirtschaft calculators in agriculture Page 1 of 344 Linn; Spike Programmable Calculators and Journal of Dairy Science 1980 5 Vol. -

HP Calculator Programming Richard J

HP Calculator Programming Richard J. Nelson Introduction Do you use an HP calculator that has a programming capability, and do you actually use it? Of the 24 models, see Table 1 below, 23 are on the HP website 13, or 54.2%, are programmable. If the Home and Office machines are omitted, the numbers are: 17 models, and 13 or 76.5%, are programmable. What does this mean? A program is a sequence of instructions (functions and/or data) that are keyed (or loaded) into the calculator’s memory that will solve a particular problem or provide specific information. A program capability also includes special instructions that provide prompting for inputs and labeling for outputs. Another aspect of a program capability is the ability to perform decision logic so the particular parts of a program may be changed depending on the results of previous instructions. This capability provides “intelligence” to the program. The program capability of the 10 current models ranges from very simple such as the HP-12C to very complex (and very powerful) such as the HP 50g. Older HP calculators such as the HP-71B or HP-75C used a computer like programming language called BASIC. The HP-12C and HP-15C programing language is an RPN FOCAL(1) like language, and the HP 50g uses an RPL programming language. The algebraic calculators use what may be called an Aplet programming language. Table 1 – Current HP Calculator Products (24) # Financial Calculators Scientific & Graphing Home & Office 1 HP 10bII HP 10s HP Calcpad 100 2 HP 10bII+ HP-15C Limited Edition HP CalcPad 200 3 HP 20b HP 33s OfficeCalc 100 4 HP 30b HP 35s OfficeCalc 200 5 HP-12C HP 39gs OfficeCalc 300 6 HP-12C 30th Anniversary HP 39gII PrintCalc 100 7 HP-17bII+ HP 40gs QuickCalc 8 HP 48gII 9 HP 50g 10 SmartCalc HP 300s 5 of 7 = 71% programmable 8 of 10 = 80% programmable None programmable Note: Programmable calculators are in blue. -

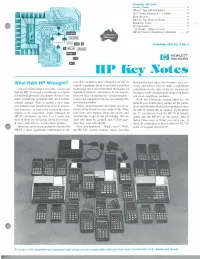

HP Key Notes

FI.b%, tLb h: Library Comer ..................... HP-41C Tips and Techniques .......... (67) Twenty-Element 4 X 5 Matrix ..... Book Reviews .................... HP-41C Tips From an Owner ......... Randomly Yours .................. We Get Letters ...................... "25 Words" (More or Less!) .......... HP-4 1C Owner's Handbook Addendum . Hovemkr lsfO Vd. 3 No. 4 HEWLETT PACKARD HP Key Notes What Hath HP Wrought? way that calculators have changed your life. It Hewlett-Packard takes this business very ser- caused a quantum jump in personal calculator iously and always tries to make a significant Can you believe that it was only 7 years ago technology and forever banished the tedium of contribution to the state of the art. So you can that the HP-35 created a worldwide revolution repetitious numeric calculations. It was respon- bet that we will continue to develop even better in handheld personal calculators? Almost over- sible not only for putting the "programmable" and more significant products. night, it made the venerable slide rule a compu- in personal calculators but also for making this With the Christmas season upon us, we tational antique. Plus, it started a very large newsletter possible. thought you might enjoy seeing all the calcu- new industry and caused most of us to restruc- Today, programmable calculators are a rela- lators that Hewlett-Packard has produced since ture our lives-at least as far as numeric calcu- tively common tool in every walk of life. They the HP-35 started this revolution. In the photo lations were concerned. And, although all save time, save money, make life easier, and are 27 calculators, with the HP-35 at bottom HP-35 calculators are now 5 to 7 years old, increase the scope of our knowledge. -

HP-15C Owner's Handbook

HP-15C Owner’s Handbook HP Part Number: 00015-90001 Edition 2.4, Sep 2011 Legal Notice This manual and any examples contained herein are provided “as is” and are subject to change without notice. Hewlett-Packard Company makes no warranty of any kind with regard to this manual, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability non- infringement and fitness for a particular purpose. In this regard, HP shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained in the manual. Hewlett-Packard Company shall not be liable for any errors or incidental or consequential damages in connection with the furnishing, performance, or use of this manual or the examples contained herein. Copyright © 2011 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, LP. Reproduction, adaptation, or translation of this manual is prohibited without prior written permission of Hewlett-Packard Company, except as allowed under the copyright laws. Hewlett-Packard Company Palo Alto, CA 94304 USA Introduction Congratulations! Whether you are new to HP calculators or an experienced user, you will find the HP-15C a powerful and valuable calculating tool. The HP-15C provides: 448 bytes of program memory (one or two bytes per instruction) and sophisticated programming capability, including conditional and unconditional branching, subroutines, flags, and editing. Four advanced mathematics capabilities: complex number calculations, matrix calculations, solving for roots, and numerical integration. Direct and indirect storage in up to 67 registers. This handbook is written for you, regardless of your level of expertise. The beginning part covers all the basic functions of the HP-15C and how to use them. -

HP 35S Scientific Calculator

HP 35s Scientific Calculator Get professional performance from the ultimate RPN scientific programmable calculator. Switch between RPN* and algebraic entry-system logic at any time. The HP 35s features a two-line display, and the powerful HP Solve** application. Ultimate pocket size performer Professionals and college students have the flexibility no other scientific calculator can offer with the choice of RPN or algebraic entry-system logic. • Choose between RPN or algebraic entry-system logic—no other scientific calculator offers both • Completely programmable—work more efficiently with keystroke programming • Handle the heaviest workloads with ease using 30 KB of memory plus 800+ independent storage registers • Store an equation then use again to solve any variable using HP Solve or use 100 built-in functions Reliable performance and accurate results The HP 35s delivers with a large 2-line alpha numeric display with adjustable contrast, raised edges to protect the keys, and a robust library of built-in functions and constants. • Large 2-line display with adjustable contrast to easily view entries, results, menus and prompts • Simplify physics with 42 built-in physical constants, plus a complete library of unit conversions • Get accurate results with edit, undo, delete capability • Enjoy a compact size and protective raised edges that are designed for the mobile professional Power and functionality in one Save time with an impressive array of programmable scientific functions. • Use strong statistics functions for single and two-variable statistics, linear regression and more • Use base-n functions for binary, octal, decimal and hexadecimal number calculation and conversion • Perform operations on complex numbers, calculate logarithms, exponentials, inverse functions and more • Take advantage of a powerful fraction mode plus fraction-to-decimal conversion HP quality and support Have confidence that every time you turn on your HP calculator, every calculation you make, results in dependable, worry-free performance and accurate results.