Caputia Tomentosa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of the Vascular Alien Flora of Catalonia (Northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3

BOTANICAL CHECKLISTS Mediterranean Botany ISSNe 2603-9109 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/mbot.63608 Checklist of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) Pere Aymerich1 & Llorenç Sáez2,3 Received: 7 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 / Published online: 7 November 2019 Abstract. This is an inventory of the vascular alien flora of Catalonia (northeastern Iberian Peninsula, Spain) updated to 2018, representing 1068 alien taxa in total. 554 (52.0%) out of them are casual and 514 (48.0%) are established. 87 taxa (8.1% of the total number and 16.8 % of those established) show an invasive behaviour. The geographic zone with more alien plants is the most anthropogenic maritime area. However, the differences among regions decrease when the degree of naturalization of taxa increases and the number of invaders is very similar in all sectors. Only 26.2% of the taxa are more or less abundant, while the rest are rare or they have vanished. The alien flora is represented by 115 families, 87 out of them include naturalised species. The most diverse genera are Opuntia (20 taxa), Amaranthus (18 taxa) and Solanum (15 taxa). Most of the alien plants have been introduced since the beginning of the twentieth century (70.7%), with a strong increase since 1970 (50.3% of the total number). Almost two thirds of alien taxa have their origin in Euro-Mediterranean area and America, while 24.6% come from other geographical areas. The taxa originated in cultivation represent 9.5%, whereas spontaneous hybrids only 1.2%. From the temporal point of view, the rate of Euro-Mediterranean taxa shows a progressive reduction parallel to an increase of those of other origins, which have reached 73.2% of introductions during the last 50 years. -

Prickly News South Coast Cactus & Succulent Society Newsletter | Feb 2021

PRICKLY NEWS SOUTH COAST CACTUS & SUCCULENT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER | FEB 2021 Guillermo ZOOM PRESENTATION SHARE YOUR GARDEN OR YOUR FAVORITE PLANT Rivera Sunday, February 14 @ 1:30 pm Cactus diversity in northwestern Argentina: a habitat approach I enjoyed Brian Kemble’s presentation on the Ruth Bancroft Garden in Walnut Creek. For those of you who missed the presentation, check out the website at https://www. ruthbancroftgarden.org for hints on growing, lectures and access to webinars that are available. Email me with photos of your garden and/or plants Brian graciously offered to answer any questions that we can publish as a way of staying connected. or inquiries on the garden by contacting him at [email protected] [email protected]. CALL FOR PHOTOS: The Mini Show genera for February are Cactus: Eriosyce (includes Neoporteria, Islaya and Neochilenia) and Succulent: Crassula. Photos will be published and you will be given To learn more visit southcoastcss.org one Mini-show point each for a submitted photo of your cactus, succulent or garden (up to 2 points). Please include your plant’s full name if you know it (and if you don’t, I will seek advice for you). Like us on our facebook page Let me know if you would prefer not to have your name published with the photos. The photos should be as high resolution as possible so they will publish well and should show off the plant as you would Follow us on Instagram, _sccss_ in a Mini Show. This will provide all of us with an opportunity to learn from one another and share plants and gardens. -

Un-Priced 2021 Catalog in PDF Format

c toll free: 800.438.7199 fax: 805.964.1329 local: 805.683.1561 text: 805.243.2611 acebook.com/SanMarcosGrowers email: [email protected] Our world certainly has changed since we celebrated 40 years in business with our October 2019 Field Day. Who knew then that we were only months away from a global pandemic that would disrupt everything we thought of as normal, and that the ensuing shutdown would cause such increased interest in gardening? This past year has been a rollercoaster ride for all of us in the nursery and landscape trades. The demand for plants so exceeded the supply that it caused major plant availability shortages, and then the freeze in Texas further exacerbated this situation. To ensure that our customers came first, we did not sell any plants out-of-state, and we continue to work hard to refill the empty spaces left in our field. In the chaos of the situation, we also decided not to produce a 2020 catalog, and this current catalog is coming out so late that we intend it to be a two-year edition. Some items listed may not be available until early next year, so we encourage customers to look to our website Primelist which is updated weekly to view our current availability. As in the past, we continue to grow the many tried-and-true favorite plants that have proven themselves in our warming mediterranean climate. We have also added 245 exciting new plants that are listed in the back of this catalog. With sincere appreciation to all our customers, it is our hope that 2021 and 2022 will be excellent years for horticulture! In House Sales Outside Sales Shipping Ethan Visconti - Ext 129 Matthew Roberts Michael Craib Gene Leisch - Ext 128 Sales Manager Sales Representative Sales Representative Shipping Manager - Vice President [email protected] (805) 452-7003 (805) 451-0876 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Roger Barron- Ext 126 Jose Bedolla Sales/ Customer Service Serving nurseries in: Serving nurseries in: John Dudley, Jr. -

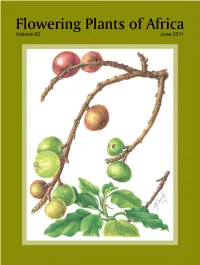

Albuca Spiralis

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

Greenhouse of UNI Del’S Greenhouse Joe and Joan Traylor Ben and Tina Donath Bev Edmondson Patricia Hampton

A special thank you to: Harry and Molly Stine and Stine Seeds Merle Philips The Shea Foundation Greenhouse of UNI Del’s Greenhouse Joe and Joan Traylor Ben and Tina Donath Bev Edmondson Patricia Hampton BUENA VISTA Iowa’s accessibly scaled, eye-opening university. Estelle Siebens Science Center 610 West Fourth Street Storm Lake, Iowa 50588 1 800 383 9600 ph www.bvu.edu Greenhouse Only in a greenhouse can you have a desert right next to a rainforest. The western most of the three rooms has a number of cacti, aloes, agaves and euphorbia collected from the American Southwest and South Africa. The middle room has many species from the warm and wet parts of our planet, several of which make good houseplants. The nearest room is reserved for research projects, new plants and display of plants that are blooming. Greenhouse funds were Rainforest provided by Stine Seeds. Bambusa verticillata (Gramineae) (Bamboo) Carissa grandiflora (Apocynaceae) (Natural Plum Jasmine) Cissus rhombifolia (Grape Ivy) Desert Citrus lemoni (Ritaceae) (Ponderosa Lemon) Adromischus cristatus (Crassulaceae)(Crinkle Leaf Plant) Cyperus alternifolius (Cyperaceae) Aloe brevifolia (Liliaceae) (Crocodile Jaws) Drypterus marginalis (Eastern Wood Fern) Astrophytum myriostigma (Cactaceae) (Bishop’s Cap) Evolvulus speciosa (Convulaceae) Bryophyllum daigremontianum (Crassulaceae) (Mother of thousands) Ficus benjamina (Braided Ficus Tree) Crassula arborescens (Crassulaceae) (Silver Dollar Jade) Ficus elastica (Rubber Plant) Crassula perforata (Crassulaceae) (String of Buttons) -

Asteraceae: Senecioneae) Ekaterina D

© © Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.zobodat.at Wulfenia 21 (2014): 111–118 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Re-considerations on Senecio oxyriifolius DC. and S. tropaeolifolius MacOwan ex F. Muell. (Asteraceae: Senecioneae) Ekaterina D. Malenkova, Lyudmila V. Ozerova, Ivan A. Schanzer & Alexander C. Timonin Summary: Analyses of ITS1-2 data from a comprehensive sample of African succulent species of Senecio and related genera reveals that Senecio tropaeolifolius, though closely related to S. oxyriifolius, should be treated as a separate species. According to our results, it may be one of the parental species to S. kleiniiformis, a widely cultivated ornamental of uncertain hybrid origin. Keywords: Asteraceae, Senecioneae, taxonomy, systematics, Senecio kleiniiformis, ITS1-2 Senecio tropaeolifolius MacOwan ex F. Muell. is a widely cultivated succulent ornamental (Brickell 2003) whose taxonomic rank has remained uncertain so far. Its similarity to S. oxyriifolius DC. was mentioned in its first description (Mueller 1867) and Rowley (1994, 2002) rendered it as a subspecies of the latter one. However, Jeffrey (1986, 1992) treated these allopatric (Fig. 1) taxa, S. tropaeolifolius and S. oxyriifolius, as two separate species in the section Peltati. According to their descriptions, these two species differ mainly in their growth form, the number of involucral bracts of the capitula, the number of florets in the capitula, the presence/absence of ray florets and bristles on cypselae. All these characters are rather variable amongSenecio L. s. latiss. and their taxonomic value is questionable. Molecular data drastically changed the understanding of taxonomy and phylogeny of Senecio and related genera (Pelser et al. -

Origin Inspection Programs (Food and Agricultural Code, Section 6404)

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE 110.1 PLANT QUARANTINE MANUAL 5 -01-12 Origin Inspection Programs (Food and Agricultural Code, Section 6404) FLORIDA No Approved Nurseries 110.2 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE 10-07-03 PLANT QUARANTINE MANUAL CUT FLOWERS INSPECTED AT ORIGIN MAY BE RELEASED The release of plant material without inspection is limited to the following types when from an approved nursery. This approval does not preclude inspection and sampling and/or testing at the discretion of the destination California Agricultural Commissioner, and rejection is required as a consequence of inspection and/or test(s). (Section 6404, Food and Agricultural Code). Hawaii Approved Nurseries, Certificate Number, and Commodities Asia Pacific Flowers, Inc., Hilo, Hawaii (HIOI-HO104) Dendrobium spp. (orchids and leis), Oncidium spp. (orchids). Big Island Floral, Pahoa, Hawaii (HIOI-O0026) No Longer A Participant. Floral Resources, Inc., Hilo, Hawaii (HIOI-H0043) Anthurium spp., Cordyline terminalis (red & green varigated ti). Goble’s Flower Farm, Kula, Hawaii (HIOI-M0076) No Longer A Participant. Gordon’s Nursery, Haleiwa, Hawaii (HIOI-00171) Dendrobium spp. (orchids), Oncidium spp. (orchids), Rumohra (Polystichum) adiantiformis (leather leaf fern from California). Green Point Nurseries, Inc., Hilo, Hawaii (HIOI-HOOO7) Anthurim spp., Cordyline terminalis (green, red, varigated ti). Green Valley Tropical, Punaluu, Hawaii (HIOI-O0136) Alpinia purpurata (red, pink ginger), Etlingera elatior (torch ginger), Zingiber spectabile (shampoo ginger), Costas pulverulentus, C. stenophyllus,Calathea crotalifera, Strelitzia reginae, Heliconia caribaea, H. bihai, H. stricta, H. orthotricha, H. bourgeana, H. indica, H. psittacorum, H. aurentiaca, H. latispatha, H. rostrata, H. pendula, H. chartacea, H. collinsiana, Anthurium andraeanum , Dendrobium spp. -

Porophyllum Ruderale) COMO ALIMENTO FUNCIONAL

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO FACULTAD DE QUÍMICA ESTUDIO DEL PÁPALOQUELITE (Porophyllum ruderale) COMO ALIMENTO FUNCIONAL T E S I S QUE PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE QUÍMICA DE ALIMENTOS P R E S E N T A MIRNA HERNÁNDEZ CARRILLO MÉXICO, D.F. 2014 1 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. JURADO ASIGNADO: PRESIDENTE: Profesor: Dra. Yolanda Caballero Arroyo VOCAL: Profesor: M. A. O. Rosa Luz Cornejo Rosas SECRETARIO: Profesor: M. en C. Martha Yolanda González Quezada 1er. SUPLENTE: Profesor: Q. A. Bertha Julieta Sandoval Guillen 2° SUPLENTE: Profesor: Q. Katia Solórzano Maldonado SITIO DONDE SE DESARROLLÓ EL TEMA: LABORATORIO 2B EDIFICIO A FACULTAD DE QUIMICA. UNAM ASESOR DEL TEMA: ______________________________ Dra. Yolanda Caballero Arroyo SUPERVISOR TÉCNICO: ______________________________ Q. Katia Solórzano Maldonado SUSTENTANTE: ______________________________ Mirna Hernández Carrillo 2 Índice Capítulo I. Introducción…………………………….............................................. 9 1.1 Objetivos………………………………………………………………….. 10 Capítulo 2. Marco teórico………………………………………………………….. 11 2.1 Justificación……………………………………………………………... 13 14 Capitulo 3. Antecedentes…………………………………………………………. 14 3.1 Quelites…………………………………………………………………... 14 3.1.1 Definición………………………………………………………. 15 3.1.2 Distribución……………………………………………………. -

A Multivariate Analysis of Variation in Cineraria Lobata L'hér. and C

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com South African Journal of Botany 73 (2007) 530–545 www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb A multivariate analysis of variation in Cineraria lobata L'Hér. and C. ngwenyensis Cron ⁎ G.V. Cron a, , K. Balkwill a, E.B. Knox b a School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Private Bag 3, Wits 2050, South Africa b Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Received 16 August 2006; received in revised form 23 April 2007; accepted 25 April 2007 Abstract Cineraria lobata is a highly variable species centred in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces, South Africa, with disjunct populations in Mpumalanga and Limpopo Provinces. Morphological variation was examined in order to delimit the species and to determine whether recognition at infraspecific levels was warranted. Plants from the Ngwenya Hills, Swaziland, similar to C. lobata in leaf shape and size, but with glabrous cypselae and a distinct type of trichome, are recognized as a distinct, but closely related species, C. ngwenyensis. Cluster Analysis and Principal Coordinates Analysis supported the recognition of four subspecies in C. lobata: from the Western Cape (ssp. lobata), Karoo (ssp. lasiocaulis), Soutpansberg (ssp. soutpansbergensis) and Eastern Cape (ssp. platyptera) regions. Five forms of C. lobata ssp. lobata from the Western Cape are also informally recognised. © 2007 SAAB. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Cineraria; Cluster analysis; Compositae; Infraspecific variation; Principal Coordinates Analysis; Senecioneae 1. Introduction gascar. Cineraria is essentially an afromontane genus, with its centre of diversity in KwaZulu-Natal, followed closely by the Cineraria L. -

Othonna CENTRAL COAST CACTUS and SUCCULENT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER •Upcoming Speaker - •Upcoming Events - •Return Library Books! •Plant of the Month - Inside This Issue

CENTRAL COAST CACTUS AND SUCCULENT SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Pismo Beach,CA93449 780 MercedSt. c/o MarkusMumper & SucculentSociety Central CoastCactus On the Dry Side November 2009 Inside this issue CCCSS October Meeting Recap •Upcoming Speaker - Rob Skillin Our club is growing, which is great but we need to have some new blood on our board. We are looking for some new officers, so think •Upcoming Events - about helping out and become a board member! Shows & Sales Our President, Mary Peracca, welcomed a few new guests this •Return library books! month, which along with the fine folks that brought snacks received •Plant of the Month - a new plant. Othonna Remember if you haven’t signed up for our Lotus Land field trip, there are a few spaces left. The trip will be Nov. 14th so call Terry Skillin ASAP if interested at 473-0788. The Board is starting to prepare for the Dec. potluck/auction. This is a fun gathering with great food and some great plants for auction. This is one not to miss, so mark your calendars for Dec. 13th. We will be accepting donations of high quality plants and more information and food sign-ups will be addressed at our next meeting. Our librarian Jeanie has purchased some new books for our library which should be in by Nov. These books will soon be listed on our website and one may reserve them through the website www.centralcoastcactus.org. Another great selection of raffle plants this month. A beautiful Adenia glauca & Fockea edulis were two of the beautiful speci- mens up for grabs. -

Crassula Catalog

SucculentShop.co.za Page: 2 CAMPFIRE CRASSULA - CRASSULA CAPITELLA The Campfire Crassula is a branching succulent with fleshy propeller-like leaves that mature from bright lime green to bright red. Leaves turn bright red if not over-watered and the plant receives direct sun for SucculentShop.co.za Page: 3 most of the day, during drought or in cold temperatures. It has a prostrate habit, forming mats about 15 cm tall and up to a meter wide. It does best in partial sun and requires more shade in hotter inland sites When grown in shade, the leaves are bright apple green for most of the year. Although fairly drought tolerant, it requires occasional watering. Spikes of insignificant white, star-shaped flowers are borne in summer and attract bees, butterflies and other tiny insects. Works very well for hanging basket gardens. Plant in full sun or partial shade. Well-drained soil. Prune after flowering. Size: up to 20cm Read More SucculentShop.co.za Page: 4 FAIRY CRASSULA - CRASSULA MULTICAVA 15 - 20 cm cutting The Fairy Crassula or Crassula multicava is a succulent herbaceous plant native to the mountainous regions of KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa). It is frequently used as a hedge plant because its stems branch off a lot of forming quite compact foliage agglomerations. It is also appreciated for its resistance to periods of drought and extreme temperatures and the beauty of its flowering. It is currently marketed as an ornamental plant in numerous nurseries worldwide. This species is characterized by forming stems erect low (generally nor exceed 25 cm) very branched and thin of green-red. -

Jade-Plants Catalog

SucculentShop.co.za Page: 2 DWARF ELEPHANT FOOD - SPEKBOOM - PORTULACARIA AFRA 'MINIMA' Dwarf version Dwarf Elephant Food is a low-growing variety of the usually upright growing succulent shrub. It grows to about 6 inches tall with a 4-6 foot spread and is excellent for use as a groundcover. Elephant Food is SucculentShop.co.za Page: 3 named for being a favorite food source for elephants in Africa. An easy care plant that does well in partial to full sun and is drought tolerant when established. Source: https://www.evergreennursery.com Read More GOLDEN JADE PLANT - LUCKY PLANT - MONEY TREE - CRASSULA OVATA ‘HUMMEL'S SUNSET' Crassula ovata, commonly known as Jade plant, Lucky plant, Money plant or Money tree is a succulent plant with small pink or white flower. It is native to South Africa and Mozambique, and is common as a houseplant. These plants can last a lifetime and grow to be very large with the proper care. Leaves stay green in low light conditions, edges will turn red in dry hot summer conditions. Tender soft succulent - will not tolerate frost. Known to bless the house in which it resides, the Jade Plant transcends cultures and language barriers to become one of the most popular succulents. Read More SucculentShop.co.za Page: 4 JADE PLANT - LUCKY PLANT - MONEY TREE - CRASSULA OVATA SucculentShop.co.za Page: 5 Crassula ovata, commonly known as Jade plant, Lucky plant, Money plant or Money tree is a succulent plant with small pink or white flower. It is native to South Africa and Mozambique, and is common as a houseplant.