Common Summer 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J. BRUCE EVANS PAPERS Mss

J. BRUCE EVANS PAPERS Mss. 4664 Inventory Compiled by Susan D. Cook Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Summer 1997 Revised 2007 J. Bruce Evans Papers Special Collections, LSU Libraries Mss. 4664 1614-2005 Contents of Inventory Summary 3 Biographical/ Historical Note 4-5 Scope and Content Note 6-7 List of Subgroups, Series and Subseries 8-9 Groups, Series and Subseries Descriptions 10-27 Index Terms 28-29 Appendices I-V 30-34 Container list 35-38 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please fill out a call slip specifying the materials you wish to see. Consult the Container list for local information needed on the call slip. Photocopying. Should you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member before segregating items to be copied. The existing order and arrangement of unbound materials must be maintained. Publication. Readers assume full responsibility for compliance with laws regarding copyright, literary property rights, and libel. Permission to examine archival and manuscript materials does not constitute permission to publish. Any publication of such materials beyond the limits of fair use requires specific prior written permission. Requests for permission to publish should be addressed in writing to the Head, LLMVC, Special Collections, LSU Libraries, Baton Rouge, LA, 70803-3300. When permission to publish is granted, two copies of the publication will be requested for the LLMVC. Proper acknowledgement of LLMVC materials must be made in any resulting writings or publications. The correct form of citation for this manuscript group is given on the summary page. -

District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites Street Address Index

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA INVENTORY OF HISTORIC SITES STREET ADDRESS INDEX UPDATED TO OCTOBER 31, 2014 NUMBERED STREETS Half Street, SW 1360 ........................................................................................ Syphax School 1st Street, NE between East Capitol Street and Maryland Avenue ................ Supreme Court 100 block ................................................................................. Capitol Hill HD between Constitution Avenue and C Street, west side ............ Senate Office Building and M Street, southeast corner ................................................ Woodward & Lothrop Warehouse 1st Street, NW 320 .......................................................................................... Federal Home Loan Bank Board 2122 ........................................................................................ Samuel Gompers House 2400 ........................................................................................ Fire Alarm Headquarters between Bryant Street and Michigan Avenue ......................... McMillan Park Reservoir 1st Street, SE between East Capitol Street and Independence Avenue .......... Library of Congress between Independence Avenue and C Street, west side .......... House Office Building 300 block, even numbers ......................................................... Capitol Hill HD 400 through 500 blocks ........................................................... Capitol Hill HD 1st Street, SW 734 ......................................................................................... -

Carl Colby Speaks About the Man Nobody Knew: in Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby

Georgetown CITIZENS V OLUME X X V I / I SSUE 4 / A PRIL 2 0 1 2 WWW . CAGTOWN . ORG Carl Colby Speaks about The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby arl Colby will be our became a major force in featured speaker at American history, paving Cthe CAG meeting on the way for today’s Tuesday April 17. He will tell provocative questions the fascinating back stories about security and secre- behind the film he made cy versus liberty and about his father, Georgetown morality. The film forges resident and former Director a fascinating mix of rare of the CIA, William E. archival footage, never- Colby: The Man Nobody before-seen photos, and Knew: In Search of My Father, Filmmaker Carl Colby interviews with the CIA Spymaster William “who’s who” of Colby. He recently produced American intelligence, including former and directed this feature- National Security Advisers Brent Scowcroft length documentary film on and Zbigniew Brzezinski, former Secretary of his late father, William E. Defense Donald Rumsfeld, former Secretary Colby, former Director of the of Defense and Director of the CIA James CIA, as well as the evolution Schlesinger, as well Pulitzer Prize journalists of the CIA from OSS in Bob Woodward, Seymour Hersh and Tim WWII to today. The story is Weiner. Through it all, Carl Colby searches a probing history of the CIA as well as a personal mem- for an authentic portrait of the man who remained oir of a family living in clandestine shadows. masked even to those who loved him. -

Concerts Honor Dads and Patriots in June and July Fly Me to the Moon

VOLUME XXXV / ISSUE 6 / SUMMER 2014 WWW.CAGTOWN.ORG Concerts Honor Dads and Patriots in June and July special prize from Rooster’s, Georgetown’s newest men’s grooming spot. Hannah Isles–Concerts Chair In addition to great music, Sprinkles will be handing out cupcakes, AG’s Concerts in the Parks 2014 season Haagen Dazs will be scooping ice cream and opened May 18th with great enthu- the Surf Side food truck will be serving up Csiasm from the citizens of Georget- tacos and other Mexi-Cali morsels. Also, many own. Over 300 people — perhaps the biggest of our sponsor tables will be hosting fun family crowd yet! — came out to enjoy the gor- activities. geous afternoon and hear Rebecca McCabe and the band Human Country Jukebox in July 13th, Rose Park for a Patriotic Volta Park. And we have only just begun! Parade Gather your blankets, chairs, picnics, pets, families and friends again for the June and July concert-goers will enjoy the lively pop/ July concerts. You don’t want to miss these: Americana sounds of Laura Tsaggaris and her band. Show your community pride and come Rebecca McCabe is joined by kids on stage. June 15th, Volta Park to celebrate Dads Photo courtesy of The Georgetowner out to celebrate Georgetown! Decorate your wagon, bike, trike, stroller and/or furry four- Calling all dads for a special Father’s Day legged friend for our patriotic parade to take celebration concert in Volta Park on Sunday, June 15th at 5:00 pm. place during intermission. The Surf Side Food Truck will again be on Dads and their families will enjoy chilling out with the southern funk hand to serve up delicious southwestern fare. -

Seduced Copies of Measured Drawings Written

m Mo. DC-671 .-£• lshlH^d)lj 1 •——h,— • ULU-S-S( f^nO District of Columbia arj^j r£Ti .T5- SEDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Building Survey National Park Service Department of the Interior" Washington, D.C 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DUMBARTON OAKS PARK HABS No. DC-571 Location: 32nd and R Sts., NW, Washington, District of Columbia. The estate is on the high ridge that forms the northern edge of Georgetown. Dumbarton Oaks Park, which was separated from the formal gardens when it was given to the National Park Service, consists of 27.04 acres designed as the "naturalistic" component of a total composition which included the mansion and the formal gardens. The park is located north of and below the mansion and the terraced formal gardens and focuses on a stream valley sometimes called "The Branch" (i.e., of Rock Creek) nearly 100' below the mansion. North of the stream the park rises again in a northerly and westerly direction toward the U.S. Naval Observatory. The primary access to the park is from R Street between the Dumbarton Oaks estate and Montrose Park along a small lane presently called Lovers' Lane. Present Owner; Dumbarton Oaks Park is a Federal park, owned and maintained by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. Dates of Construction: Dumbarton Oaks estate was acquired by Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss in 1920. At their request, Beatrix Jones Farrand, a well- known American landscape architect, agreed to undertake the design and oversee the maintenance of the grounds. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Capital Region Rock Creek Park 3545 Williamsburg Lane, N.W. Washington, DC 20008-1207 l .A.2 (NCR-ROCR) FEB 27 2020 Mr. David Maloney State Historic Preservation Officer Attn: Mr. Andrew Lewis DC Historic Preservation Office Office ofPlanning 1100-4th Street, SW, Suite E650 Washington, DC 20024 RE: Rock Creek Park - Unified Signage Plan - Seeking Review and Concurrence to Finding of No Adverse Effect Dear Mr. Maloney: The National Park Service (NPS) is continuing the planning for a proposal to develop a unified plan for signage for U.S. Reservation 339 and other properties administered by Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC, including units ofthe Civil War Defenses ofWashington. As such, we seek your review and comment on the proposed undertaking. Existing signage within Rock Creek Park and its administered sites is inconsistent with modem standards, having been installed incrementally over the last 20 years. Further, many areas are lacking identification and visitor wayfinding. This plan represents a sign palette or system that can be used and implemented in the future and provides a consistent and unified look. Signs being designed under this project include park identity signs, roadway signs, and trail signs. The proposed system is based on a modem Uni Guide system and standards, and is being developed by Hunt Designs, which developed the sign system for the National Mall and Memorial Parks. Please find enclosed the final sign plan and renderings for your review. Please note, the signs will not all be replaced at once. Instead, replacement and installation of new signs will occur in phases when funding is available, or when an existing sign is at the end of its useable life. -

A History of Land, Labor and People of the Dumbarton Oaks Estate Until

A History of the Land, Labor, and People of the Dumbarton Oaks Estate Until 1920 Cassandra Luca A.B. Candidate in English, Harvard College Class of 2021 Summer Intern June-August 2019 Luca 2 Introduction I would first like to acknowledge that this report was written on occupied lands of the Algonquin Nation. As a settler scholar who does not share the lived experiences of Native and Black communities, I have attempted to capture as accurately as possible the experiences of the Native Americans and enslaved people whose lives are chronicled in the following pages. This work is especially important because early settlers took the land and resources upon which Native Americans had relied for generations, and because the enslaved people who lived here continue to remain nameless despite their presence and livelihood on this land. This report is a review of previously-known sources of information concerning the history of the Dumbarton Oaks estate, incorporating newly-found documents which aim to present a more complete picture of the individuals on the property throughout its history. Rather than explicitly answering some questions concerning the labor or agricultural production of the estate, many of the new details provide a larger context through which to better understand the owners. This report is organized chronologically by owner, followed by a discussion section addressing the questions arising from the information presented. Before Ninian Beall’s Arrival Native Americans were part of the landscape in and around the property that is now Dumbarton Oaks for about 13,000 years, long before the arrival of British colonizers. -

CAG Salutes Oral History Pioneers at City Tavern Club Recent Public

VOLUME XXIX / ISSUE 9 / NOVEMBER 2013 WWW.CAGTOWN.ORG CAG Salutes Oral History Pioneers at City Tavern Club n Wednesday, November 20, CAG will hear families, building businesses, entertaining, renovat- from well-known Georgetowners Pie Friendly, ing houses – and more. OBilly Martin, Steve Kurzman, Barbara Downs, and Chris Murray, all of whom have participated in Our host for the evening will be the City Tavern CAG’s oral history project. These engaging Georget- Club who will provide refreshments for the recep- owners have recorded their recollections about life in tion starting at seven o’clock. The City Tavern Club Georgetown in one-on-one interviews with CAG’s oral also invites CAG members to continue the evening history volunteers. The results have been fascinating – following the Oral History panel by offering a cash visit www.cagtown.org to read the summaries andor bar beginning at 8:30 and the opportunity to have the entire interviews. Come and meet these living a three course dinner for $35 per person. RSVP by Georgetown legends and hear some of their intriguing Thursday, November 14, to Sue Hamilton at 333- stories first hand. 8076 or [email protected]. Tom Birch will introduce the program with a sum- Please join CAG at the elegant City Tavern Club, mary of the project. The interviewees will then talk 3206 M Street, for an evening filled with well-de- City Tavern Club hosts CAG informally about their memories of growing up in or meeting November 20 served salutes to significant Georgetowners -- and moving to Georgetown, pursuing careers here, raising their role in capturing the history of Georgetown. -

Invasive Species in the Historic Dumbarton Oaks Garden

Invasive Species in the Historic Garden: A Field Guide to Dumbarton Oaks Dumbarton Oaks Internship Report Joan Chen Summer intern ‘18, Garden & Landscape Studies Master of Landscape Architecture ‘19, Harvard GSD August 3, 2018 This report provides a brief overview of Beatrix Farrand’s use of plant species that are currently considered “invasive” and outlines management strategies. Farrand’s Plant Book for Dumbarton Oaks, written in 1941 and published by Dumbarton Oaks in 1980, is the main text referenced by this report. The Garden Archives at Dumbarton Oaks, as well as conversations with gardeners, also shaped this study. Two case studies explore how invasive species management might be approached in a historic garden. A spreadsheet with each mention of an invasive plant in Farrand’s Plant Book and its associated management strategies is included in the Appendix, providing a working document for Garden and Grounds staff. The Appendix also contains a brief reading list with titles on garden history, the native/non-native/invasive plant debate, and various plant lists and technical references, as well as a printable pamphlet with information on the six most used invasive plants at Dumbarton Oaks. Overview When Beatrix Farrand described plant growth as invasive, the term “invasive species” had not yet come into use. Her 1941 plant book includes two uses of the word “invasive” while describing maintenance of fast-spreading plants: At the little porter’s lodge, Ivy and Wisteria are used on the building itself, but here again they must not be allowed to become so invasive that the lodge is turned into a green mound. -

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES in the HISTORY of ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O

CULTURAL NEGOTIATIONS CRITICAL STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Series Editors: Regna Darnell, Stephen O. Murray Cultural Negotiations The Role of Women in the Founding of Americanist Archaeology DAVID L. BROWMAN University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London © 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Browman, David L. Cultural negotiations: the role of women in the founding of Americanist archaeology / David L. Browman. pages cm.— (Critical studies in the history of anthropology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8032-4381-1 (cloth: alk. paper) 1. Women archaeologists—Biography. 2. Archaeology—United States—History. 3. Women archaeologists—History. 4. Archaeologists—Biography. I. Title. CC110.B76 2013 930.1092'2—dc23 2012049313 Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington. Designed by Nathan Putens. Contents Series Editors’ Introduction vii Introduction 1 1. Women of the Period 1865 to 1900 35 2. New Directions in the Period 1900 to 1920 73 3. Women Entering the Field during the “Roaring Twenties” 95 4. Women Entering Archaeology, 1930 to 1940 149 Concluding Remarks 251 References 277 Index 325 Series Editors’ Introduction REGNA DARNELL AND STEPHEN O. MURRAY David Browman has produced an invaluable reference work for prac- titioners of contemporary Americanist archaeology who are interested in documenting the largely unrecognized contribution of generations of women to its development. Meticulous examination of the archaeo- logical literature, especially footnotes and acknowledgments, and the archival records of major universities, museums, field school programs, expeditions, and general anthropological archives reveals a complex story of marginalization and professional invisibility, albeit one that will be surprising neither to feminist scholars nor to female archaeologists. -

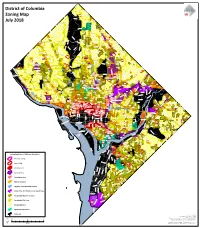

Pending Zoning Ac Ve PUD Pending PUD Campus Plans Downtown

East Beach Dr NW Beach North Parkway Portal District of Columbia Eastern Ave NW R-1-A Portal Dr NW Parkside Dr NW Kalmia Rd NW 97-16D Zoning Map 32nd St NW RA-1 12th St NW Wise Rd NW MU-4 R-1-B R-2 16th St NW R-2 76-3 Geranium St NW July 2018 Pinehurst Parkway Beech St NW Piney Branch Portal Aberfoyle Pl NW WR-1 RA-1 Alaska Ave NW WR-2 Takoma MU-4"M Worthington St NW WR-3 Dahlia St NW MU-4 WR-4 NC-2 R-1-A WR-6 RA-1 Utah Ave NW 31st Pl NW WR-6 MU-4 WR-5 RA-1 WR-7 Sherrill Dr NW WR-8 WR-3 MU-4 WR-5 Aspen St NW Nevada Ave NW Stephenson Pl NW Oregon Ave NW 30th St NW RA-2 4th St NW R-2 Van Buren St NW 2nd St NW Harlan Pl NW Pl Harlan R-1-B Broad Branch Rd NW Luzon Ave NW R-2 Pa�erson St NW Tewkesbury Pl NW 26th St NW R-1-B Chevy Tuckerman St NE Chase NW Pl 2nd Circle MU-3 Sheridan St NW Blair Rd NW Beach Dr NW R-3 MU-3 MU-3 MU-4 R-1-B Mckinley St NW Fort Circle Park 14th St NW Morrison St NW PDR-1 1st Pl NE 05-30 R-2 R-2 RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Missouri Ave NW Peabody St NW Francis G. RA-1 04-06 Lega�on St NW Newlands Park RA-2 (Little Forest) Eastern Ave NE Morrow Dr NW RA-3 MU-7 Oglethorpe St NE Military Rd NW 2nd Pl NW 96-13 27th St NW Kanawha St NW Fort Slocum Friendship Heights Nicholson St NW Park MU-7 MU-5A R-2 R-2 "M Fort R-1-A NW St 9th Reno Rd NW Glover Rd NW Circle 85-20 R-3 Fort MU-4 R-2 NW St 29th Park MU-5A Circle Madison St NW MU-4 Park R-3 R-1-A RF-1 PDR-1 RA-2 R-8 RA-2 06-31A Fort Circle Park Linnean Ave NW R-16 MU-4 Rock Creek Longfellow St NW Kennedy St NE R-1-B RA-1 MU-4 RA-4 Ridge Rd NW Park & Piney MU-4 R-3 MU-4 Kennedy St NW -

A Good Home for a Poor Man

A Good Home for a Poor Man Fort Polk and Vernon Parish 1800 – 1940 Steven D. Smith A Good Home for a Poor Man Fort Polk and Vernon Parish 1800–1940 Steven D. Smith 1999 Dedicated to Andrew Jackson “Jack” Hadnot, John Cupit, Erbon Wise, John D. O’Halloran, Don Marler, Mary Cleveland, Ruth and John Guy, Martha Palmer, and others who have wrest from obscurity the history of Vernon Parish. This project was funded by the Department of Defense’s Legacy Resource Management Program and administered by the Southeast Archeological Center of the National Park Service under Cooperative Agreement CA-5000-3-9010, Subagreement CA-5000-4-9020/3, between the National Park Service and the South Carolina Institute of Archaeol- ogy and Anthropology, University of South Carolina. CONTENTS FIGURES......................................................................................................................................................6 TABLES .......................................................................................................................................................8 PREFACE .....................................................................................................................................................9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..........................................................................................................................10 CHAPTER 1 — BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 11 The Purpose of This Book