The Third Option: Removing Urban Highways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

PE Individuals 013013 1

REGISTERED PROFESSIONAL ENGINEERS EXPIRES JUNE 30, 2013 PE REG. NAME COMPANY NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP NO. ABBASZADEH RAMIN GREY FOX CONSULTING, INC. 57 COOPER AVE CHERRY HILL, NJ 08002 7978 ABDELRHMAN MOHAMED A. 303 GREENWICH AVE, #A-222 WARWICK, RI 02886 5823 ABEL DENNIS D. 61655 KINGSTON COURT SOUTH BEND, IN 46614 7739 ABELY JAMES J. 354 BEACON STREET #4 BOSTON, MA 02116 5380 ABRAHAMS MICHAEL J. 7 NORTH ST OLD GREENWICH, CT 06870 6933 ABRAMS TED A. 117 KELEKENT LANE CARY, NC 27518 9329 ABSHAGEN TIMOTHY C. 11211 FALL GARDEN LANE KNOXVILLE, TN 37932 9070 ABU-YASEIN OMAR ALI A & A ENGINEERING 5911 RENAISSANCE PL, STE B TOLEDO, OH 43623 8380 ADAJIAN EDWARD ADAJIAN ENGINEERING, INC. 50 ALBANY TURNPIKE CANTON, CT 06019 4908 ADAMEDES THOMAS C. 500 BROADWAY NEWPORT, RI 02840 3621 ADAMO CARL J. 66 GRANDVIEW AVENUE LINCOLN, RI 02865 4211 ADAMS CHRISTOPHER J. NELCO ENGINEERING 12400 COIT RD, STE 510 DALLAS, TX 75251 9578 ADAMS JASON C. JASON C. ADAMS, PE SUITE 5268 1805 N 2ND STREET ROGERS, AR 72756 9381 ADAMS ROBERT B. METCALF & EDDY, INC. 701 EDGEWATER DR WAKEFIELD, MA 01880 7159 ADAMS SCOTT N. ADVANCED ENGINEERING GROUP, PC 500 NORTH BROADWAY EAST PROVIDENCE, RI 02914 8120 ADDISON JOHN D. 1280 W Peachtree St NW, #3403 ATLANTA, GA 30309 9380 ADEEB KAREEM 71 OLD FARM RD FAIRFIELD, CT 06825-2033 6355 ADELSBEmRGER CHARLES 60 LORRAINE METCALF DRIVE WRENTHAM, MA 02093 5824 AGBAYANI NESTOR A. AGBAYANI STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING 1201 24TH STREET, SUITE B110-116 BAKERFIELD, CA 93301-2391 9753 AGHJAYAN DOUGLAS J. GEI CONSULTANTS, INC. -

North Coast NCRD Breaks Ground for New Pickleball Courts

Keepsake Graduation Serving North Tillamook County since 1996 Section Inside North Coast HOME Spr ing - Summer IMPROVEMENT 2020 Section Inside Impr ovement ITIZEN $1 C June 4, 2020 northcoastcitizen.com Volume 26, No. 10 NCRD breaks ground for new pickleball courts n May 29, NCRD $10,100 from the pickle- designing the courts. Bids held a groundbreak- ball club, $1,400 from the were invited in March and ingO ceremony on its 7th Friends of NCRD, and the McEwan Construction of street lot in downtown Ne- balance from NCRD. Gearhart was awarded the halem. About 30 members This project began contract in April. of the community attended with a series of discus- The new courts will be to celebrate the beginning sions dating back to late on a mostly vacant lot fac- of construction of four new 2017 when the Nehalem ing 7th street in downtown pickleball courts. Bay Pickleball Club Nehalem, adjacent to the Manning the shovels approached NCRD with NCRD obstacle course. were NCRD board chair a demonstrated need for The club currently has 60 Jack Bloom, Nehalem Bay new courts in the area. members but everyone Pickleball Club President Eventually a plan was involved is predicting Gordon Louie, Friends of developed for fundraising there will be many new NCRD President Con- and community support, players once the courts stance Shimek, and Mi- and by January, 2019, are finished. Pickleball is chael McEwan from Mc- a grant application was reported to be the fastest Ewan Construction. The submitted to Oregon Parks growing sport in America. NCRD board chair Jack Bloom, Nehalem Bay Pickleball Club President Gordon project funding includes a and Recreation. -

Dod 4000.24-2-S1, Chap2b

DOD 4LX)0.25-l -S1 RI RI CODE LOCATION AND ACTTVITY DoDAAD CODE COOE LOCATION ANO ACTIVITY DoDAAD COOE WFH 94TH MAINT SUP SPT ACTY GS WE 801S7 SPT BN SARSS-I SARSS-O CO B OSU SS4 BLDG 1019 CRP BUILDING 5207 FF STEWART &! 31314-5185 FORT CAMPBELL KY 42223-5000 WI EXCESS TURN-IN WG2 DOL REPARABLE SARSS 1 SARSS-1 REPARABLE EXCHANGE ACTIVITY B1OG 1086 SUP AND SVC DW DOL BLOC 315 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFJ 226TH CS CO WG3 MAINTENANCE TROOP SARSS-1 SUPPORT SQUAORON BLDG 1019 3D ARMORED CALVARY REGIMENT FT STEWART GA 31314-5185 FORT BLISS TX 79916-6700 WFK 1015 Cs co MAINF WG4 00L VEHICLE STORAGE SARSS 1 SARSS-I CLASS N Iv Vll BLDG 403 F7 GILLEM MF CRP SUP AND SVC OIV 00L BLDG 315 FOREST PARK GA 30050-5000 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 W-L 1014 Cs co WG5 DOL ECHO OSU .SAFfSS 1 SARss-1 EXCESS WAREHOUSE 2190 WINIERVILLE RD MF CRP SUP ANO SVC DIV 00L BLOG 315 ATHENS GA 30605-2139 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 WFM 324TH CS BN MAINT TECH SHOP WG6 SUP LNV DOL CONSOL PRDP ACCT SARSS-1 MF CRP SUP AND SVC DIV DOL BLDG 315 BLOC 224 FORT CARSON CO 80913-5702 FT BENNING GA 31905-5182 WG7 HQS ANO HQS CO OISCOM SARSS2A WFN 724TH CS BN CA A DSU CL9 1ST CAV OW OMMC SARSS-I BLDG 32023 BLDG 1019 FORT HOOD TX 76545-5102 FF STEWART GA 31314-5185 WG8 71OTH MSB HSC GS WFP STOCK RECORD ACCT . -

San Diego Unified Port District Document No. 65336 Filed 07/22/16

(114) San Diego Unified Port District Document No. 65336 Filed 07/22/16 Carrier Johnson CCI Partners Cook and Schmid Moff att & Nichol Randall Lamb Associates Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects San Diego Board of Port Commissioners November 2015 CONTENTS FRAMEWORK REPORT I. Introduction • Background ................................................................................................................... 4 • The Integrated Planning Vision................................................................................... 6 • Guiding Principles......................................................................................................... 6 • Planning Principles...................................................................................... 8 • Values and Standards............................................................................... 10 II. Outline of the Framework Report • Why a Framework Report........................................................................................... 14 • How to Use This Document....................................................................................... 14 • Glossary of Terms........................................................................................................ 14 • Framework Report Appendices................................................................................. 17 III. Comprehensive Ideas • Land Use, Water Use, and Mobility........................................................................... 22 • Public Access and Recreation.................................................................................. -

View a PDF Version

see things in a new light The splendor of Westinghouse Lighting fixtures, ceiling fans and light bulbs reveals the eye-catching style and beauty of your home. To learn more, call 800-999-2226 or visit www.westinghouselighting.com. , WESTINGHOUSE, and INNOVATION YOU CAN BE SURE OF are trademarks of Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Used under license by Westinghouse Lighting. All Rights Reserved. 2019 WESTINGHOUSE LIGHTING 984_ALADirectoryAD_2019.inddALA AD Pages_2020.indd 1 1 10/16/194/7/20 1:04 1:14 PM PM “I set the lights to come on at dusk so my family always comes back to a welcoming home... especially when I am out of town.” — Philadelphia, PA Upgrade your life. Start with peace of mind. Discover how to personalize your home with Caséta lighting controls: dimmers, remotes, mobile app, or your own voice activated device. Simple to use and easy to set up. Visit CasetaWireless.com. Seamlessly integrates with: by ©2019 Lutron Electronics Co., Inc. Lutron is a trademark of Lutron Electronics Co., Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. For a complete list of all Lutron registered and common law trademarks, please visit lutron.com/trademarks. HomeKit is a trademark of Apple Inc. ALA AD Pages_2020.indd 2 4/7/20 1:04 PM Table of Contents 2020 ACTION AGENDA INDEX Advertising Marketing & Communications .............d-e Education ...................................................................f 2020 Annual Conference ...........................................g Training & Certification ..............................................h-i -

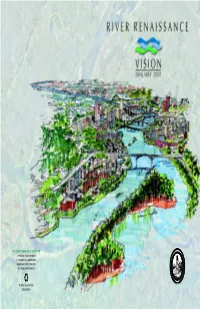

River Renaissance Vision Is a Sketch of the Willamette River As Portlanders Would Like to See It in the Future

DOCUMENT DESIGN AND ILLUSTRATION Jim Ann Carter, Graphic Illustrator II Jim Longstreth, Illustrator/Consultant Vickie Nissen, Illustrator/Consultant Gary Odenthal, GIS Coordinator Printed on Recycled Paper Second Edition BUREAU OF PLANNING 1900 SW 4th Ave., Ste. 4100 Portland, Oregon 97201 503.823.5839 [email protected] www.planning.ci.portland.or.us C1 I ◆ JANUARY 26, 2051 C2 I CITY Portland: Reflections on the River CLOSE-UP Portland’s 200th Birthday reduce the toxicity of roadway runoff The waterfront is now one of the best Continued from Page C1 reaching the river. venues to learn about and appreciate City’s Return to the River Portland and its evolution. Early use of River taxis, ferries, tour boats, and cruise the river by indigenous cultures is hon- Fifty years ago the water was fouled. Early in the century, major investments ships have also made the waterfront more ored at sites along the waterfront. Repli- Toxic substances penetrated the sedi- were made to clean up the toxics in Port- context, accommodating the river’s ex- accessible and popular. Convenient boat cas of early Portland ships and maritime Reminiscing on the legacy of ments on the river bottom, the fish were land Harbor and all but eliminate sewer panded natural and recreational func- access from waterfront destinations and museums connect Portlanders to the River Renaissance, launched at unhealthy to eat, and the banks were overflows into the river. tions and the prevention and cleanup neighborhoods is provided by access city’s river and economic heritage. Rem- the turn of the millennium lined with concrete and construction of river pollution. -

Towers, Terraces Imagined at Riverplace Redevelopment in Downtown Portland

PORTLAND Towers, terraces imagined at RiverPlace redevelopment in downtown Portland Today 7:00 AM Kengo Kuma and Associates via City of Portland A rendering of the "Portland Steps" open space concept designed by Kengo Kuma and Associates of Tokyo for a proposed redevelopment in Portland's RiverPlace district. 44 54 shares By Elliot Njus | The Oregonian/OregonLive A Portland development firm that has amassed eight acres of property south of downtown near city’s waterfront plans a tower district with a striking public plaza designed by a star Japanese architect. The deMenutails are included in NSPetB Capital’s recently released master plan for tSubscribehe area, offering the first Weather public look at the site’s design after a City Council debate earlier this year on height limits. Sign In Search / The council voted to allow towers up to 325 feet on parts of the site — the same height as some of the tallest buildings in the nearby South Waterfront district. RiverPlace lies along the Willamette River between Tom McCall Waterfront Park and the South Waterfront, separated from downtown by busy stretches of Harbor Drive and Naito Parkway. The master plan as proposed could bring up to 2,500 new apartments in several buildings to the spot, along with an office tower. They would share a large underground parking garage. Because any housing project would be subject to a 2017 city mandate that developers include rent- restricted units in any new housing, it would also add hundreds of affordable apartments. Architects for NPB Capital presented the master plan last week to the Portland Design Commission. -

2019 Project

2019 Central City Development & Redevelopment Projects - MAP 1. Oro Portland 34. Pearl Self Storage 67. Landing at Macadam 99. Erickson Saloon/Fritz Hotel 132. Miracles Central Apartments 2. Modera Glisan 35. Pearl East 68. 15 NE Broadway 100. 38 Davis 133. Hassalo on Eighth 3. The Rodney 36. Fremont Place 69. Veterans Memorial Coliseum 101. The Hoxton 134. The Union 4. Modera Davis 37. 1319 NW Johnson 70. Grand Ave. Apartments 102. Powell’s City of Books 135. The Fair-Haired Dumbbell 5. Harlow Building 38. Fire Station 71. Weatherly Building 103. 12W STARK 136. Aura Burnside 6. 230 Ash 39. 815 W. Burnside 72. 1120 SE Morrison 104. Woodlark House 137. Towne Storage 7. Hyatt Centric 40. Joyce Hotel 73. OMSI District Plan 105. Pine Street Market 138. Hotel Eastlund 8. 902-18 SW 3rd Ave. & 250 TAYLOR 41. New Market Addition 74. ODOT Block 5 106. HiLo Hotel 139. St. Francis Park Apartments 9. The Moxy 42. Toyoko Inn 75. Riverscape 107. Pioneer Place 140. The Linden 10. 10th & Yamhill Smartpark 43. Healy Building 76. Field Office 108. Meier & Frank Building 141. Templeton Building 11. Multnomah County Courthouse 44. Morrison Bridgehead 77. 9NORTH 109. Park Avenue West 142. Block 76 West 12. The Portland Building 45. Block 216 78. Pearl Housing 110. Galt House 143. The Yard 13. Wells Fargo Center 46. 11 West 79. The Abigail 111. 1155 SW Morrison St. 144. The Slate 14. 140 SW Columbia 47. Portland Art Museum 80. Broadstone Reveal 112. The Cameron 145. Shleifer Warehouse 15. KOZ on 4th 48. 1430 SW Park 81. -

2019 1120 Riverplace

RIVERPLACE CENTRAL CITY MASTER PLAN DESIGN ADVICE REQUEST #2 EA 19 -215959 DA December 5 2019 EASTBANK GBD Architects Incorporated 1120 NW Couch St., Suite 300 Portland, OR 97209 Tel. (503) 224-9656 www.gbdarchitects.com This is the submittal package for the Design Advice Request #2 for RiverPlace. At the first Design Advice Request meeting on October 3, 2019 the Design Commission identified areas within the proposed development for additional studies. The topics that drew the most discussion included: • The size and scale of the western block • The location of required open space at the podium level of the western block • Implementation of a potential new pedestrian / bicycle bridge across SW Harbor Drive In addition to new material on these topics, the first part of the submittal includes the Central City 2035 Plan Goals and descriptions of how the development proposal broadly addresses them. This submittal also includes updated information on the proposed street network options for RiverPlace and massing envelopes for future buildings. Over the course of developing the design options for this proposal, the project team has convened a series of meetings with various public agencies, neighborhood organizations and community groups. Though this is not an all inclusive accounting, the team has organized a transportation and traffic related meeting with the Downtown Neighborhood Association (DNA), formally met and presented the project to the DNA 2 times, met with the Bureau of Transportation 7 times, the Bureau of Environmental Services 2 times and the Bureau of Development Services 3 times. NBP Capital | Riverplace Redevelopment DESIGN ADVICE REQUEST EA 19-215959 DA December 5, 2019 2 RIVERPLACE POLICY GOALS 1. -

Agenda12-Attachment

AGENDA12-ATTACHMENT Rule 11-18: Potentially Subject Sites High Priority Sites (1) 58 Medium Priority Sites (2) 334 Total Sites: 392 Location Location Priority Facility# Facility Name Location Address Location City Location County State Zip Code 1 3194 City of Alameda, Maint Serv Doolittle Drive Alameda Alameda CA 94501 Center 1 11326 PE Berkeley, Inc Univ of Calif, Berkeley Berkeley Alameda CA 94720 Campus 1 22605 Pacific Steel Casting Company 1328 2nd Street Berkeley Alameda CA 94710 LLC 1 2246 Tri-Cities Recycling 7010 Auto Mall Pkwy Fremont Alameda CA 94538 1 16248 Comcast of California IX Inc 395 Mowry Boulevard Fremont Alameda CA 94536 1 22076 City of Fremont 2000 Stevenson Blvd Fremont Alameda CA 94538 1 19495 Alameda County Public Works lndstrial Flood, Control Hayward Alameda CA 94541 Agency Pump Station 1 2066 Waste Management of 10840 Altamont Pass Rd Livermore Alameda CA 94551 Alameda County 1 5095 Republic Services Vasco Road, 4001 N Vasco Road Livermore Alameda CA 94550 LLC 1 62 A B & I Foundry 7825 San Leandro St Oakland Alameda CA 94621 1 678 Port of Oakland #1 Airport Drive Oakland Alameda CA 94621 1 20072 Kaiser Permanente 5840 Owens Drive Pleasanton Alameda CA 94588 1 12728 Waste Management Inc 2615 Davis Street San Leandro Alameda CA 94577 1 19746 FXI, Inc 2451 Polvorosa Street San Leandro Alameda CA 94577 1 20448 San Francisco Public Utilities 8653 Calaveras Rd Sunol Alameda CA 94586 Commission 1 11 Shell Martinez Refinery 3485 Pacheco Blvd Martinez Contra Costa CA 94553 Page 1 AGENDA12-ATTACHMENT 1 1820 Martinez Cogen -

Download PDF File Waterfront Park Master Plan

Waterfront Park Master Plan Portland, Oregon Acknowledgments Jim Francesconi, Commissioner Natural Resource Planning Services, Zari Santner, Director Robert Dillinger Charles Jordan, Director (former) Helen Lessick, Artist John Sewell, Chief Planner (former) Jeanne Lawson Associates, Vaughn Brown Janet Bebb, Planning Supervisor Graphic Design Portland Parks and Recreation Viviano Design, Inc., Jennifer Viviano Project Team Citizens Advisory Committee David Yamashita, Project Manager and Harriet Cormack, Chair Principal Author Rob DeGraff Gay Greger, Public Involvement Coordinator Sho Dozono Bryan Aptekar, Public Involvement Assistant Larry Dully Kathleen Wadden, Senior Management Analyst Carol Edelman Glenn Raschke, Planning and Development José Gonzalez Webmaster Jeffry Gottfried Chris Hathaway Consultant Team John Helmer, Jr. EDAW, Inc. Steve Johnson Jacinta McCann, Principal Gregg Kantor Steve Hanson, Project Manager/ David Krause Landscape Architect Mauricio Leclerc Megan Walker, Landscape Architect Marty McCall Lango Hansen, Kurt Lango Kathryn Silva Grummell Engineering, Bob Grummell Paddy Tillett Technical Advisory Committee Operations, Bob Downing Bureau of Environmental Services, Doug Sowles Operations, Brian McNerney Bureau of Environmental Services, Operations, Tom Dufala Dawn Uchiyama Operations, Kathy Murrin Portland Department of Transportation, Recreation, Lisa Turpel Roger Geller Recreation, Bob Schulz Bureau of Planning, River Renaissance, Recreation, Shawn Rogers Sallie Edmunds Recreation, Cary Coker Bureau of Planning,