Toccata Classics TOCC0175 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viola Concerto) and 23 January 2009 (Symphony No

Recorded in Studio 1, BBC Maida Vale, London, on 24–25 January 2013 (Viola Concerto) and 23 January 2009 (Symphony No. 2) Recording engineer: Neil Pemberton Producer: Ann McKay Music published by Peters Edition The composer would like to thank the following for their generous financial support of this CD: Keith and Margaret Stanley, Gerry Wakelin, The John S. Cohen Foundation and The RVW Trust. Booklet notes: Giles Easterbrook and Matthew Taylor Design and layout: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford Executive producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0175 © BBC/Toccata Classics 2013. The copyright in the recording is jointly owned by the BBC and Toccata Classics. The BBC, BBC Radio 3 and BBC Symphony Orchestra word marks and logos are trade-marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 2013 P 2013, Toccata Classics, London Britten’s The Turn of the Screw and Raskatov’s A Dog’s Heart for English National Opera, Cimarosa’s The Secret Marriage for Scottish Opera, Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito at the Royal Northern College of Music and MATTHEW TAYLOR: A BIOGRAPHICAL OUTLINE Poulenc’s La Voix Humaine at the Linbury Studio Theatre at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Outside the UK he as conducted Curlew River for Lyon Opera and a new production by Calixto Bieito of Hosakawa’s by Giles Easterbook Hanjo at the Ruhr Triennale. Future plans include appearances with the Adelaide Symphony, a return visit to the Auckland Matthew Taylor’s music combines traditional forms with a contemporary language which speaks to a wide Philharmonic, Pacific Symphony Orchestra, Dortmund Philharmoniker, Musikkollegium Winterthur, BBC range of listeners, taking its part in the symphonic narrative that blossomed with the ‘first Viennese school’ of National Orchestra of Wales and the BBC Scottish Orchestra. -

The Lullaby Concerts 2009–2018

THE LULLABY CONCERTS 2009–2018 AN OVERVIEW OF THE LULLABY CONCERTS Orchestras Live developed the Lullaby concert series in partnership with City of London Sinfonia, as a response to the need for Early Years music making opportunities in rural and culturally undeserved areas in the east of England. Our aim was to develop inspiring, interactive and relevant ways to engage very young children (aged up to 7 years) in first-time experiences of live orchestral music. This included a long-term approach to artistic exploration with our creative partners, responding to the needs and priorities of the communities where the work was based. Evolving from a series of pilot projects started in 2003, the Lullaby concerts reached over 20,000 young children and their families in Suffolk and Essex over 10 years. For many this was their first experience of live orchestral music, and these encounters have often inspired children to take up an instrument or other creative activity, as well as encouraging families to experience more live music together. Each year the concert series, performed by City of London Sinfonia and led by presenter Claire Henry, engaged children through vivid worlds such as animals, forests and science; telling musical stories through everyday themes. After each concert the children in the audience had a chance to try orchestral instruments, supported by professional players and tutors. Over the 10 years the programme involved 727 Early Years practitioners in a CPD training development strand linked to the Lullaby concerts; the Lullaby artistic team shared appropriate skills and ideas which practitioners could take back and use in their nursery settings. -

ECONOMIC EAR Symphonic Tigers and Chamber Kittens

ANALYSIS ECONOMIC EAR Symphonic tigers and chamber kittens In the fifth of our series of articles on the business of classical music, Antony Feeny reflects on the extent to which the UK music industry may be dominated by a few large organisations ans Sachs was a remarkably like to ensure free competition and level example, and the top four supermarkets and productive artist if the com- playing fields, those pesky markets persist in top four banks have over 70% of the British mon sources are to be believed. becoming more concentrated and awkward grocery store and retail banking markets, HIn addition to keeping the inhabitants of ruts will keep appearing in those playing while the top six energy suppliers account Nürnberg well-heeled, he apparently cob- fields. And so it seems with classical music. for 90% of the UK market. But these are bled together 4,000 Meisterlieder between Was Le Quattro Staggioni – well-known (relatively) free markets where commercial 1514 and his death in 1576. That’s about to every denizen of coffee shops and call cen- companies compete, so what’s the situa- one every five-and-a-half days every year tres – really so much ‘better’ than works by tion for classical music – a market which is for 62 years including Sundays, in addition the Allegris, the Caccinis, Cavalli, Fresco- subsidised and where its leading organisa- to his other 2,000 poetic works – not to baldi, the Gabrielis, Landi, Rossi, Schütz, or tions are best semi-commercial, or at least mention shoes for the 80,000 feet of those the hundreds of other 17th-century compos- non-profit-making? Nurembergers, or at least the wealthy ones. -

Download Booklet

• • • BAX DYSON VEALE BLISS VIOLIN CONCERTOS Lydia Mordkovitch violin London Philharmonic Orchestra • City of London Sinfonia BBC Symphony Orchestra • BBC National Orchestra of Wales Richard Hickox • Bryden Thomson Nick Johnston Nick Lydia Mordkovitch (1944 – 2014) British Violin Concertos COMPACT DISC ONE Sir Arnold Bax (1883 – 1953) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra* 35:15 1 I Overture, Ballade and Scherzo. Allegro risoluto – Allegro moderato – Poco largamente 14:47 2 II Adagio 11:41 3 III Allegro – Slow valse tempo – Andante con moto 8:45 Sir George Dyson (1883 – 1964) Violin Concerto† 43:14 4 I Molto moderato 20:14 5 II Vivace 5:08 6 III Poco andante 10:39 7 IV Allegro ma non troppo 7:06 TT 78:39 3 COMPACT DISC TWO Sir Arthur Bliss (1891 – 1975) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra‡ 41:48 To Alfredo Campoli 1 I Allegro ma non troppo – Più animato – L’istesso tempo – Più agitato – Tempo I – Tranquillo – Più animato – Tempo I – Più animato – Molto tranquillo – Moderato – Tempo I – Più mosso – Animato 15:43 2 II Vivo – Tranquillo – Vivo – Meno mosso – Animando – Vivo 8:49 3 III Introduzione. Andante sostenuto – Allegro deciso in modo zingaro – Più mosso (scherzando) – Subito largamente – Cadenza – Andante molto tranquillo – Animato – Ancora più vivo 17:10 4 John Veale (1922 – 2006) Violin Concerto§ 35:38 4 I Moderato – Allegro – Tempo I – Allegro 15:55 5 II Lament. Largo 11:47 6 III Vivace – Andantino – Tempo I – Andantino – Tempo I – Andantino – Tempo I 7:53 TT 77:36 Lydia Mordkovitch violin London Philharmonic Orchestra* City of London Sinfonia† BBC National Orchestra of Wales‡ Lesley Hatfield leader BBC Symphony Orchestra§ Stephen Bryant leader Bryden Thomson* Richard Hickox†‡§ 5 British Violin Concertos Bax: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra on the manuscript testifies) but according Sir Arnold Bax’s (1883 – 1953) career as an to William Walton, Heifetz found the music orchestral composer started in 1905 with disappointing. -

Resonate: Centuries of Meditations by Dobrinka Resonate: Centuries of Meditations by Dobrinka

https://prsfoundation.com/2019/04/23/new‐resonate‐pieces‐announced/ Home > New Resonate Pieces Announced UK orchestras to champion 11 of the best pieces of British orchestral music from the past 25 years through PRS Foundation’s Resonate programme. Orchestras supported include City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Ulster Orchestra, Dunedin Consort & Scottish Ensemble, and the London Symphony Orchestra Pieces selected include Oliver Knussen’s The Way to Castle Yonder – Pot‐pourri after the Opera Higglety, Pigglety Pop, Thomas Adès’ Violin Concerto ‘Concentric Paths’ and Four Tributes to 4 am by Anna Meredith PRS Foundation, the UK’s leading funder of new music and talent development across all genres announces the 10 UK orchestras being supported through the third round of Resonate, a partnership with the Association of British Orchestras and BBC Radio 3, which champions outstanding pieces of British orchestral music from the past 25 years and aims to inspire more performances, recordings and broadcasts of these works. The orchestras and Resonate pieces to be programmed into their upcoming 2019/20 programmes are: Aurora Orchestra: Thomas Adès, Violin Concerto ‘Concentric Paths’ London Philharmonic Orchestra: Ryan Wigglesworth, Augenlieder City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra: Oliver Knussen, The Way to Castle Yonder – Pot‐pourri after the Opera Higglety, Pigglety Pop London Symphony Orchestra: Colin Matthews, Violin Concerto Dunedin Consort & Scottish Ensemble: James MacMillan, Seven Last Words from the Cross Southbank Sinfonia: Anna Meredith, Four Tributes to 4 am City of London Sinfonia (CLS): Dobrinka Tabakova, Centuries of Meditations Ulster Orchestra: Howard Skempton, Lento Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (Ensemble 10/10): Steve Martland, Tiger Dancing and Tansy Davies, Iris Birmingham Contemporary Music Group: Shiori Usui, Deep Resonate is a fund and resource which aims to inspire more performances, recordings and broadcasts of outstanding contemporary repertoire, as chosen by UK orchestras. -

Yers On-Line in the Virtual Bar

BOOK YOUR TICKETS VIA TEXT CLAP, CHAT AND INTERACT MEET THE CONDUCTOR AND players ON-LINE IN THE virtual BAR POST YOUR REVIEW ON THE ORCHESTRA’S WEBSITE DOWNLOAD A PODCAST OF THE GIG CREATE NEXT SEASON’S PROGRAMME SHARE YOUR VIEWS VIA TWITTER BECOME PART OF THE ORCHESTRA’S GLOBAL ‘COMMUNITY’ GET MUSIC TUITION FROM THE ORCHESTRA PLAYERS VIA THE WEB TAKE A WEEKEND TRIP TO THE FIRST EVER ORCHESTRAL DIGITAL INSTALLATION . A NEW ORCHESTRAL EXPERIENCE BOOK YOUR TICKETS VIA TEXT CLAP, CHAT AND INTERACT MEET THE CONDUCTOR AND players ON-LINE IN THE virtual BAR POST YOUR REVIEW ON THE ORCHESTRA’S WEBSITE DOWNLOAD A PODCAST OF THE GIG CREATE NEXT SEASON’S PROGRAMME SHARE YOUR VIEWS VIA TWITTER BECOME PART OF THE ORCHESTRA’S GLOBAL ‘COMMUNITY’ GET MUSIC TUITION FROM THE ORCHESTRA PLAYERS VIA THE WEB TAKE A WEEKEND TRIP TO THE FIRST EVER ORCHESTRAL DIGITAL INSTALLATION . A NEW ORCHESTRAL EXPERIENCE Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment’s Night Shift: Joe Plommer INTRODUCTION In a fast-paced world where people want excellence on and experimenting with new techniques and technologies demand, orchestras are stepping up to the challenge. in their day-to-day activities. And like any industry the orchestral world cannot afford to Modern orchestral performers are not only stand still. exceptional musicians; they are also exceptional People want to access music in ways that suit them communicators, leaders, improvisers and teachers. - without compromising on quality. Embracing new Orchestras must continue to adapt to the evolving technology is key to modernising the concert experience; demands of current and future audiences. -

EIC0396 Written Evidence Submitted by 245 West End and Orchestral Musicians Submission Authors Please See Annex A

EIC0396 Written evidence submitted by 245 West End and Orchestral Musicians Submission Authors Please see Annex A. Submission Remit Further to the Treasury Select Committee’s call for evidence this submission attempts to address the following questions in relation to the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme: Where has Government support been too generous and where has it not been generous enough? What gaps in coverage still remain and are changes required to increase their effectiveness? How should the Government prioritise which continuing sectors and groups to support as time goes on and ongoing support is needed? Submission Summary There are substantial gaps in the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme, leaving 1.2 million self-employed workers – around a quarter of the self-employed workforce – without any form of government help, including the country’s leading West End and orchestral musicians who are suffering immense hardship; There is no basis for applying an eligibility past earnings “cap” of £50,000 for self-employed workers, without there being a similar cap for PAYE workers. We submit that it should be removed, tapered or at the very least raised to £200,000 so that it matches what the Chancellor set out when he announced the scheme; Live performance venues were the first businesses to shut their doors and will be the last to open, likely remaining out of bounds for many months given that the performance of live music and the gathering of audiences is the antithesis of social distancing. Therefore we submit that those who work in the music industry should be entitled to some very specific and targeted help so that we avoid decimating the British music industry; A lot of attention has been paid to UK sport but we must be equally vigilant when it comes to protecting our culture. -

“FROM BINGO to BARTOK” * Creative and Innovative Approaches to Involving Older People with Orchestras

“FROM BINGO TO BARTOK” * Creative and Innovative Approaches to Involving Older People with Orchestras *Participant feedback, Creative Journeys: Sinfonia Viva, South Holland District Council, Orchestras Live • INTRODUCTION 1. MUSIC FOR A WHILE 3. FINLAND: CULTURAL WELLBEING 5. PRACTICAL APPROACHES 7. A RELAXED APPROACH 9. DESK RESEARCH • EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2. MUSIC IN MIND 4. HEAR AND NOW 6. CREATIVE JOURNEYS 8. RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTRODUCTION I am sure that the majority of people reading this introduction Creative Health called for artists, health and social care will hardly need persuading of the need for and benefits of providers, local communities and funders to work together to engaging vulnerable older people with the arts. We have an support better lives longer lived. From Bingo to Bartok shows ageing population, which in turn has huge societal impact, how orchestras can contribute to this important activity, thanks with whom the arts play a vital role in promoting wellbeing and to an increasingly creative and professional approach, with quality of life. evidence of its effectiveness. The desk research shows an impressive reach; however there are many more communities In July 2017, my colleagues and I on the All-Party Parliamentary and individuals from a much wider geographical reach who Group for Arts, Health and Wellbeing, published Creative would benefit from the creative and innovative approaches that Health: The Arts for Health and Wellbeing. Our key findings orchestras can bringing to older people. Similarly, health and included evidence that the arts can support longer lives better social care providers should take note of the distinctive benefits lived, and can help to meet many of the challenges surrounding that orchestras and their musicians can bring, from specific ageing including health and social care, loneliness and clinical outcomes to the sheer joy and enjoyment of music- mental health. -

A Tribute to William Pleeth Royal College of Music Amaryllis Fleming Concert Hall Sunday 20Th November 2016

LONDON CELLO SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1098381 A Tribute to William Pleeth Royal College of Music Amaryllis Fleming Concert Hall Sunday 20th November 2016 ‘Whenever we make a stroke with our bow, when we place a finger on a string, we cause a sensation of sound and feeling; and the gesture of the bow and of the finger which brought that sound into existence must breathe with the life of the emotion that gave birth to it.’ William Pleeth ‘Wiliam Pleeth’s enthusiasm is absolutely boundless and anyone who comes into contact with him and his teaching will be able to feed from his love for music.’ Jacqueline du Pré 3 Participating Artists Anthony Pleeth and Tatty Theo Alasdair Beatson, piano Lana Bode, piano Adrian Brendel, Natasha Brofsky, Colin Carr, Nicholas Parle, harpsichord Thomas Carroll, Robert Cohen, Rebecca Gilliver, Sacconi Quartet, Quartet in Association at the John Heley, Frans Helmerson, Seppo Kimanen, Royal College of Music Joely Koos, Stephen Orton, Melissa Phelps, Hannah Catherine Bott, presenter Roberts, Sophie Rolland, Christopher Vanderspar, Kristin von der Goltz, Jamie Walton RCM Cello Ensemble with Richard Lester The London Cello Society extends its warmest thanks and appreciation to the Royal College of Music and J & A Beare for their gracious support of this event. To the Pleeth family and to all the artists who are taking part today, we are deeply grateful to you for making this celebration possible, a testimony to the high esteem in which William Pleeth is held by the cello community in the United Kingdom and abroad. Afternoon Events 2.00 PM RCM Cello Ensemble P. -

Mark Morris Dance Group

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Friday, May 29, 2009, 8pm Saturday, May 30, 2009, 8pm Sunday, May 31, 2009, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Mark Morris Dance Group Craig Biesecker Samuel Black Joe Bowie Elisa Clark Amber Darragh† Rita Donahue Domingo Estrada, Jr.‡ Lauren Grant John Heginbotham David Leventhal Laurel Lynch Bradon McDonald Dallas McMurray Maile Okamura June Omura Noah Vinson Jenn Weddel Julie Worden Michelle Yard Lesley Garrison Claudia MacPherson Kanji Segawa Billy Smith Utafumi Takemura Prentice Whitlow † on leave ‡ apprentice Mark Morris, Artistic Director Nancy Umanoff,Executive Director MetLife Foundation is the Mark Morris Dance Group’s Official Tour Sponsor. Major support for the Mark Morris Dance Group is provided by Carnegie Corporation of New York, JP Morgan Chase Foundation, The Howard Gilman Foundation, Independence Community Foundation, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Shubert Foundation, and Jane Stine and R. L. Stine. The Mark Morris Dance Group New Works Fund is supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, The Untitled Foundation, The Shelby and Frederick Gans Fund, Meyer Sound/Helen and John Meyer, and Poss Family Foundation. The Mark Morris Dance Group’s performances are made possible with public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs; the New York State Council on the Arts, a State Agency; and the National Endowment for the Arts Dance Program. Cal Performances’ presentation of L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato is made possible by the National Endowment for the Arts’ American Masterpieces: Dance Initiative, administered by the New England Foundation for the Arts, and by Bank of America. -

Tri-Borough Executive Decision Report

Executive Decision Report Decision maker(s) at each authority and date of Cabinet meeting, Cabinet Member meeting or (in the case of individual Cabinet Cabinet Member for Planning Policy, Member decisions) Transport and the Arts, Councillor Tim the earliest date the Coleridge decision will be Date of decision 7 January 2014 taken Forward Plan reference: 04129/13/P/A Report title (decision AWARD OF CONTRACT FOR PROVISION OF ORCHESTRA subject) TO OPERA HOLLAND PARK. Reporting officer Head of Culture, Ian McNicoll Key decision Yes Access to Public information classification 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. The City of London Sinfonia orchestra has been highly acclaimed as part of OHP productions over the years by critics and audience. This paper recommends the Council enters into a one year contract (with the option to extend for a further year) with the City of London Sinfonia as the resident orchestra for Opera Holland Park, 2014 at an annual fee of £340,000 plus VAT. 1.2. Due to the long-term artistic relationship that has been developed over ten years, as well as knowledge of the industry and the costs of other orchestras, the only provider that could fulfil the engagement, particularly within the existing budgets is the City of London Sinfonia. Therefore, it is proposed to not hold a competition to determine the award of contract in 2014. This is permissible under the Public Contract Regulations 2006 as it is a Part B service. This permits the Council to not hold a competition for the contract due to artistic reasons. However, it is proposed that a full tender exercise is conducted to award the contract in 2015 to demonstrate value for money. -

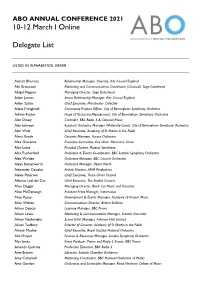

10-12 March I Online Delegate List

ABO ANNUAL CONFERENCE 2021 10-12 March I Online Delegate List LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER Aakash Bharania Relationship Manager, Diversity, Arts Council England Abi Groocock Marketing and Communications Coordinator (Classical), Sage Gateshead Abigail Pogson Managing Director, Sage Gateshead Adam Jeanes Senior Relationship Manager, Arts Council England Adam Szabo Chief Executive, Manchester Collective Adele Franghiadi Community Projects Officer, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Adrian Rutter Head of Orchestra Management, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Alan Davey Controller, BBC Radio 3 & Classical Music Alan Johnson Assistant Orchestra Manager (Maternity Cover), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Alan Watt Chief Executive, Academy of St Martin in the Fields Alana Grady Concerts Manager, Aurora Orchestra Alex Gascoine Executive Committee Vice Chair, Musicians' Union Alex Laing Principal Clarinet, Phoenix Symphony Alex Rutherford Orchestra & Events Co-ordinator, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra Alex Walden Orchestra Manager, BBC Concert Orchestra Alexa Butterworth Orchestra Manager, Opera North Alexander Douglas Artistic Director, ADM Productions Alexis Paterson Chief Executive, Three Choirs Festival Alfonso Leal del Ojo Chief Executive, The English Concert Alice Dagger Managing Director, Black Cat Music and Acoustics Alice McDonough Assistant Artist Manager, Intermusica Alice Pusey Development & Events Manager, Academy of Ancient Music Alice Walton Communications Director, Britten Sinfonia Alison Dancer Learning Manager, BBC