Historical Paper in Surgery a Brief History of Shock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derived Resuscitation Fluids on Euvolemic and Hypovolemic Rats

PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGES INDUCED BY INTRAVENOUS INFUSION OF KERATIN- DERIVED RESUSCITATION FLUIDS ON EUVOLEMIC AND HYPOVOLEMIC RATS By FIESKY A. NUÑEZ JR, MD A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Physiology and Pharmacology May 2012 Winston-Salem, North Carolina ApProved by Thomas L. Smith, PhD, Advisor Mark Van Dyke, PhD, Chair George Christ, PhD Patricia Gallagher, PhD Ann Tallant, PhD DEDICATION To my wife: Alejandra, your infinite patience and understanding allowed me to mature as a Person and as a scientist. Without you I would not have accomplished this feat. I love you To my Parents, for your unconditional support that allowed this road to be filled with joy and success. To my sister: Mary, your wisdom and emotional suPPort gave me the strength and hope I needed in order to achieve many things. You always make me think of a better tomorrow and a better me. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special Thanks to: Tom: For your impeccable mentorshiP and disPosition to always put my best interests first. Mark: For your dedication and Patience to teach such an impatient subject. Mike: For your knowledge and hard work in day-to-day lab efforts. Maria: Thank you for your patience in the lab and for sharing your immense knowledge of keratin with me. Keratin Krew and Biomaterials core: Roche, Bailey, Chris, Lauren, Mary, Julie, Jill, Carmen, DeePika. Your collaborations allow individual contributions to flourish into an extraordinary lab. OrthoaPedic Lab: Beth, Eileen, Martha, Jan, Casey. -

National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative

EXCLUSION CRITERIA NATIONAL CARDIOGENIC SHOCK INITIATIVE Evidence of Anoxic Brain Injury Unwitnessed out of hospital cardiac arrest or any cardiac arrest in which ROSC is not ALGORITHM achieved in 30 minutes IABP placed prior to Impella Septic, anaphylactic, hemorrhagic, and neurologic causes of shock Non-ischemic causes of shock/hypotension (Pulmonary Embolism, Pneumothorax, INCLUSION CRITERIA Myocarditis, Tamponade, etc.) Active Bleeding Acute Myocardial Infarction: STEMI or NSTEMI Recent major surgery Ischemic Symptoms Mechanical Complications of AMI EKG and/or biomarker evidence of AMI (STEMI or NSTEMI) Cardiogenic Shock Known left ventricular thrombus Hypotension (<90/60) or the need for vasopressors or inotropes to maintain systolic Patient who did not receive revascularization blood pressure >90 Contraindication to intravenous systemic anticoagulation Evidence of end organ hypoperfusion (cool extremities, oliguria, lactic acidosis) Mechanical aortic valve ACCESS & HEMODYNAMIC SUPPORT Obtain femoral arterial access (via direct visualization with use of ultrasound and fluoro) Obtain venous access (Femoral or Internal Jugular) ACTIVATE CATH LAB Obtain either Fick calculated cardiac index or LVEDP IF LVEDP >15 or Cardiac Index < 2.2 AND anatomy suitable, place IMPELLA Coronary Angiography & PCI Attempt to provide TIMI III flow in all major epicardial vessels other than CTO If unable to obtain TIMI III flow, consider administration of intra-coronary ** QUALITY MEASURES ** vasodilators Impella Pre-PCI Door to Support Time Perform Post-PCI Hemodynamic Calculations < 90 minutes 1. Cardiac Power Output (CPO): MAP x CO Establish TIMI III Flow 451 Right Heart Cath 2. Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index (PAPI): sPAP – dPAP Wean off Vasopressors & RA Inotropes Maintain CPO >0.6 Watts Wean OFF Vasopressors and Inotropes Improve survival to If CPO is >0.6 and PAPI >0.9, operators should wean vasopressors and inotropes and determine if Impella can be weaned and removed in the Cath Lab or left in place with transfer to ICU. -

THE CARDIO-CIRCULATORY EFFECTS in MAN of NEO- SYNEPHRIN (1-Α-Hydroxy-Β-Methylamino-3-Hydroxy- Ethylbenzene Hydrochloride)

THE CARDIO-CIRCULATORY EFFECTS IN MAN OF NEO- SYNEPHRIN (1-α-hydroxy-β-methylamino-3-hydroxy- ethylbenzene hydrochloride) Ancel Keys, Antonio Violante J Clin Invest. 1942;21(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI101270. Research Article Find the latest version: https://jci.me/101270/pdf THE CARDIO-CIRCULATORY EFFECTS IN MAN OF NEO-SYNEPHRIN (1-a-hydroxy-,8-methylamino-3-hydroxy-ethylbenzene hydrochloride) 1 BY ANCEL KEYS AND ANTONIO VIOLANTE (From the Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene, Medical School, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis) (Received for publication June 20, 1941) Neo-synephrin 2 differs chemically from epi- at least one day was allowed to elapse between studies nephrine only in the absence of the hydroxy group on any one subject. The general procedure in all studies was the same. para on the benzene ring. The in the position The subject rested quietly for 10 to 30 minutes and then first pharmacological studies with this substance measurements and observations were begun and continued emphasized the conclusion that the pharmacologi- for 10 minutes or more before the drug was adminis- cal action of neo-synephrin resembles that of epi- tered. Observations were continued for 1 to 4 hours nephrine in all respects, but the potency is less and following the administration. In all cases blood pressure the duration of effects is longer (12, 13, 21). and pulse rate were measured at frequent intervals throughout the entire experimental period. The same Inspection of the data in these papers shows, how- observer measured blood pressures throughout any one ever, that the pressor effect is relatively much experiment. -

What Is Sepsis?

What is sepsis? Sepsis is a serious medical condition resulting from an infection. As part of the body’s inflammatory response to fight infection, chemicals are released into the bloodstream. These chemicals can cause blood vessels to leak and clot, meaning organs like the kidneys, lung, and heart will not get enough oxygen. The blood clots can also decrease blood flow to the legs and arms leading to gangrene. There are three stages of sepsis: sepsis, severe sepsis, and ultimately septic shock. In the United States, there are more than one million cases with more than 258,000 deaths per year. More people die from sepsis each year than the combined deaths from prostate cancer, breast cancer, and HIV. More than 50 percent of people who develop the most severe form—septic shock—die. Septic shock is a life-threatening condition that happens when your blood pressure drops to a dangerously low level after an infection. Who is at risk? Anyone can get sepsis, but the elderly, infants, and people with weakened immune systems or chronic illnesses are most at risk. People in healthcare settings after surgery or with invasive central intravenous lines and urinary catheters are also at risk. Any type of infection can lead to sepsis, but sepsis is most often associated with pneumonia, abdominal infections, or kidney infections. What are signs and symptoms of sepsis? The initial symptoms of the first stage of sepsis are: A temperature greater than 101°F or less than 96.8°F A rapid heart rate faster than 90 beats per minute A rapid respiratory rate faster than 20 breaths per minute A change in mental status Additional symptoms may include: • Shivering, paleness, or shortness of breath • Confusion or difficulty waking up • Extreme pain (described as “worst pain ever”) Two or more of the symptoms suggest that someone is becoming septic and needs immediate medical attention. -

Update on Volume Resuscitation Hypovolemia and Hemorrhage Distribution of Body Fluids Hemorrhage and Hypovolemia

11/7/2015 HYPOVOLEMIA AND HEMORRHAGE • HUMAN CIRCULATORY SYSTEM OPERATES UPDATE ON VOLUME WITH A SMALL VOLUME AND A VERY EFFICIENT VOLUME RESPONSIVE PUMP. RESUSCITATION • HOWEVER THIS PUMP FAILS QUICKLY WITH VOLUME LOSS AND IT CAN BE FATAL WITH JUST 35 TO 40% LOSS OF BLOOD VOLUME. HEMORRHAGE AND DISTRIBUTION OF BODY FLUIDS HYPOVOLEMIA • TOTAL BODY FLUID ACCOUNTS FOR 60% OF LEAN BODY WT IN MALES AND 50% IN FEMALES. • BLOOD REPRESENTS ONLY 11-12 % OF TOTAL BODY FLUID. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HYPOVOLEMIA • SUPINE TACHYCARDIA PR >100 BPM • SUPINE HYPOTENSION <95 MMHG • POSTURAL PULSE INCREMENT: INCREASE IN PR >30 BPM • POSTURAL HYPOTENSION: DECREASE IN SBP >20 MMHG • POSTURAL CHANGES ARE UNCOMMON WHEN BLOOD LOSS IS <630 ML. 1 11/7/2015 INFLUENCE OF ACUTE HEMORRHAGE AND FLUID RESUSCITATION ON BLOOD VOLUME AND HCT • COMPARED TO OTHERS, POSTURAL PULSE INCREMENT IS A SENSITIVE AND SPECIFIC MARKER OF ACUTE BLOOD LOSS. • CHANGES IN HEMATOCRIT SHOWS POOR CORRELATION WITH BLOOD VOL DEFICITS AS WITH ACUTE BLOOD LOSS THERE IS A PROPORTIONAL LOSS OF PLASMA AND ERYTHROCYTES. MARKERS FOR VOLUME CHEMICAL MARKERS OF RESUSCITATION HYPOVOLEMIA • CVP AND PCWP USED BUT EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES HAVE SHOWN A POOR CORRELATION BETWEEN CARDIAC FILLING PRESSURES AND VENTRICULAR EDV OR CIRCULATING BLOOD VOLUME. Classification System for Acute Blood Loss • MORTALITY RATE IN CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS Class I: Loss of <15% Blood volume IS NOT ONLY RELATED TO THE INITIAL Compensated by transcapillary refill volume LACTATE LEVEL BUT ALSO THE RATE OF Resuscitation not necessary DECLINE IN LACTATE LEVELS AFTER THE TREATMENT IS INITIATED ( LACTATE CLEARANCE ). Class II: Loss of 15-30% blood volume Compensated by systemic vasoconstriction 2 11/7/2015 Classification System for Acute Blood FLUID CHALLENGES Loss Cont. -

A New Treatment for Abdominal Surgical Shock

Where it is possible the mucous membrane of and the skin is closed, except for a point at the the roof of the canal should not be destroyed and lower angle through which the catheter is brought the ends of the urethra will thus be prevented out. When the closure of the wound is complete, from retracting excessively. In the worst cases, ¿he patient is placed in a horizontal position, the where the urethra has been practically destroyed, catheter is adjusted at the proper point and is transverse division may be necessary. In many then fastened in position by a suture in the skin. of the inflammatory strictures, however, it is After-treatment. The important points in the possible to leave this strip on the roof which does after-treatment are— the care of the anterior not in any way interfere with the free mobilization urethra and the retention of the catheter until the of the anterior segment. For convenience of wound is completely healed. The care of the description, the steps of the operation will be anterior urethra has been described above, and given in order. the essential thing is that the urethra should be (1) With the patient in the lithotomy position a kept entirely clean with some solution which will free median incision is made down to the urethra, not produce undue irritation, and by some method dividing the structures of the bulb in the median which will not traumatize the suture. It has line and turning them aside. It is important that seemed to us that injection with a small syringe is this incision should be carried well backward so preferable to irrigation, either with a catheter or that the membranous urethra can be exposed. -

Coronary Thrombosis

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1938 Coronary thrombosis R. W. Karrer University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Karrer, R. W., "Coronary thrombosis" (1938). MD Theses. 669. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/669 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORONARY THROMBOSIS by R. w. Karrer Senior Thesis presented to the College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Omaha, 1938. 480947 INTRODUCTION The terms coronary thrombosis, coronary occlusion, and cardiac or myocardial infarction are often em- ployed as synonyms, although there are useful differences in their meanings. In this thesis the author will deal only with that special type of coronary occlusion in which coronary thrombosis is the final event in the process of occlusion. Also, the thesis will be limited, more or less, to that type of thrombosis which is acute thrombosis of a coronary artery, rather than to the chronic type which is neither as spec tacular a disease nor as clean cut in its clinical picture. The definition of coronary thrombosis as given by Dorland {1935} is, "The formation of a clot in a branch of the coronary arteries which supply blood to the heart muscle, resulting in obstruction of the artery and infarction of the area of the heart supplied by the occluded vessel." Cecil (1935) modifies the definition in that he mentions the obstruction is generally acute. -

Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting

9/3/2020 Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting 1 9/3/2020 Special Thanks to Our Sponsor 2 9/3/2020 Your Presenters Dr. Raymond L. Fowler, Dr. Melanie J. Lippmann, MD, FACEP, FAEMS MD FACEP James M. Atkins MD Distinguished Professor Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine of Emergency Medical Services, Brown University Chief of the Division of EMS Alpert Medical School Department of Emergency Medicine Attending Physician University of Texas Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital Southwestern Medical Center Providence, RI Dallas, TX 3 9/3/2020 Scenario SHOCK INDEX?? Pulse ÷ Systolic 4 9/3/2020 What is Shock? Shock is a progressive state of cellular hypoperfusion in which insufficient oxygen is available to meet tissue demands It is key to understand that when shock occurs, the body is in distress. The shock response is mounted by the body to attempt to maintain systolic blood pressure and brain perfusion during times of physiologic distress. This shock response can accompany a broad spectrum of clinical conditions that stress the body, ranging from heart attacks, to major infections, to allergic reactions. 5 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Shock may be caused when oxygen intake, absorption, or delivery fails, or when the cells are unable to take up and use the delivered oxygen to generate sufficient energy to carry out cellular functions. 6 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Hypovolemic Shock Distributive Shock Inadequate circulating fluid leads A precipitous increase in vascular to a diminished cardiac output, capacity as blood vessels dilate and which results in an inadequate the capillaries leak fluid, translates into delivery of oxygen to the too little peripheral vascular resistance tissues and cells and a decrease in preload, which in turn reduces cardiac output 7 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Cardiogenic Shock Obstructive Shock The heart is unable to circulate Obstruction to the forward flow of sufficient blood to meet the blood exists in the great vessels metabolic needs of the body. -

Cardiac Shock-Wave Therapy in the Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease

Burneikaitė et al. Cardiovascular Ultrasound (2017) 15:11 DOI 10.1186/s12947-017-0102-y REVIEW Open Access Cardiac shock-wave therapy in the treatment of coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis Greta Burneikaitė1,2,7*, Evgeny Shkolnik3,4, Jelena Čelutkienė1,2*, Gitana Zuozienė1,2, Irena Butkuvienė1,2, Birutė Petrauskienė1,2, Pranas Šerpytis1,2, Aleksandras Laucevičius1,5 and Amir Lerman6 Abstract Aim: To systematically review currently available cardiac shock-wave therapy (CSWT) studies in humans and perform meta-analysis regarding anti-anginal efficacy of CSWT. Methods: The Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Medline, Medscape, Research Gate, Science Direct, and Web of Science databases were explored. In total 39 studies evaluating the efficacy of CSWT in patients with stable angina were identified including single arm, non- and randomized trials. Information on study design, subject’s characteristics, clinical data and endpoints were obtained. Assessment of publication risk of bias was performed and heterogeneity across the studies was calculated by using random effects model. Results: Totally, 1189 patients were included in 39 reviewed studies, with 1006 patients treated with CSWT. The largest patient sample of single arm study consisted of 111 patients. All selected studies demonstrated significant improvement in subjective measures of angina symptoms and/or quality of life, in the majority of studies left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion improved. In 12 controlled studies with 483 patients included (183 controls) angina class, Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) score, nitrates consumption were significantly improved after the treatment. In 593 participants across 22 studies the exercise capacity was significantly improved after CSWT, as compared with the baseline values (in meta-analysis standardized mean difference SMD = −0.74; 95% CI, −0.97 to −0.5; p < 0.001). -

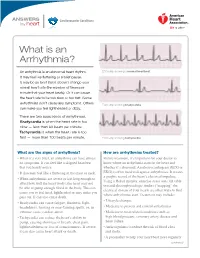

What Is an Arrhythmia?

ANSWERS Cardiovascular Conditions by heart What is an Arrhythmia? An arrhythmia is an abnormal heart rhythm. ECG strip showing a normal heartbeat It may feel like fluttering or a brief pause. It may be so brief that it doesn’t change your overall heart rate (the number of times per minute that your heart beats). Or it can cause the heart rate to be too slow or too fast. Some arrhythmias don’t cause any symptoms. Others ECG strip showing bradycardia can make you feel lightheaded or dizzy. There are two basic kinds of arrhythmias. Bradycardia is when the heart rate is too slow — less than 60 beats per minute. Tachycardia is when the heart rate is too fast — more than 100 beats per minute. ECG strip showing tachycardia What are the signs of arrhythmia? How are arrhythmias treated? • When it’s very brief, an arrhythmia can have almost Before treatment, it’s important for your doctor to no symptoms. It can feel like a skipped heartbeat know where an arrhythmia starts in the heart and that you barely notice. whether it’s abnormal. An electrocardiogram (ECG or • It also may feel like a fluttering in the chest or neck. EKG) is often used to diagnose arrhythmias. It creates a graphic record of the heart’s electrical impulses. • When arrhythmias are severe or last long enough to Using a Holter monitor, exercise stress tests, tilt table affect how well the heart works, the heart may not test and electrophysiologic studies (“mapping” the be able to pump enough blood to the body. -

The Action of Epinephrin Upon the Muscle Tissue of the Vein

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 18 Annual Issue Article 27 1911 The Action of Epinephrin upon the Muscle Tissue of the Vein J. T. M'Clintock Copyright ©1911 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation M'Clintock, J. T. (1911) "The Action of Epinephrin upon the Muscle Tissue of the Vein," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 18(1), 125-129. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol18/iss1/27 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M'Clintock: The Action of Epinephrin upon the Muscle Tissue of the Vein THE ACTION OF EPINEPHBIN UPON THE MUSCLE TISSUE OP THE VEIN. The physiology of the venous circulation has, in comparison to that of the arterial, received very little consideration. It has been looked upon as a circulation carried on in a system of inert, elastic tubes, carrying the blood back to the heart from the periphery and without much, if any, physiological action on the part of the venous wall in the process. We are in the habit of looking to the heart, the arterial tension and the skeletal muscle action as being the forces driving the blood through the venous system. The venous part of the circulation is of equal importance to the arterial, for under the conditions as they exist the one cannot be with out the other and it is hardly to be expected that in so important a process the tissue would be left with only the physical force of elas ticity upon which to depend for meeting the variable conditions to which it must be subjected. -

Distributive Shock

ASK THE EXPERT h EMERGENCY MEDICINE/CRITICAL CARE h PEER REVIEWED Distributive Shock Garret E. Pachtinger, VMD, DACVECC VETgirl; Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Center Levittown, Pennsylvania Clinical Clues YOU HAVE ASKED ... Distributive shock is generally associ- What is distributive shock, and ated with altered vasomotor tone— notably inappropriate vasodilation (eg, how do I treat it? sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome), excessive vasoconstriction THE EXPERT SAYS ... (eg, following trauma or anaphylaxis), or abnormalities in normal blood flow Shock (ie, inadequate cellular energy (eg, obstructive diseases such as gastric production or the body’s inability to dilatation-volvulus [GDV] or pericardial supply cells and tissues with oxygen and effusion)—resulting in maldistribution nutrients and remove waste products1-3) of blood flow. can cause quick clinical deterioration and requires rapid identification and Patients with septic distributive shock treatment. Distributive shock is a gen- often have hyperemic mucous mem- eral classification for syndromes that branes caused by uncontrolled vasodila- cause massive maldistribution of blood tion from inflammatory mediators and flow (seeReferences , page 96). Anaphy- cytokine release (see References, page lactic, obstructive, and septic shock are 96). Patients with anaphylactic or GDV = gastric dilatation- common forms of distributive shock. obstructive distributive shock show volvulus October 2016 cliniciansbrief.com 93 ASK THE EXPERT h EMERGENCY MEDICINE/CRITICAL CARE h PEER