542 Bound Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sen. Dorothy Eck (D) Sen

MINUTES MONTANA SENATE 55th LEGISLATURE - REGULAR SESSION COMMITTEE ON PUBLIC HEALTH, WELFARE, & SAFETY Call to Order: By CHAIRMAN STEVE BENEDICT, on January 10, 1997, at 1:00 PM, in Room 410. ROLL CALL Members Present: Sen. Steve Benedict, Chairman (R) Sen. Chris Christiaens (D) Sen. Bob DePratu (R) Sen. Dorothy Eck (D) Sen. Sharon Estrada (R) Sen. Eve Franklin (D) Sen. Fred Thomas (R) Members Excused: Sen. Larry L. Baer (R) Members Absent: Sen. James H. "Jim" Burnett, Vice Chairman (R) Staff Present: Susan Fox, Legislative Services Division Karolyn Simpson, Committee Secretary Please Note: These are summary minutes. Testimony and discussion are paraphrased and condensed. Committee Business Summary: Hearing(s) & Date(s) Posted: SB 8, SB 14, SB 23, 12/31/96 Executive Action: None {Tape: 1; Side: A; Approx. Time Count: 1:00 PM} Introductory Meeting & Procedures discussion: CHAIRMAN STEVE BENEDICT welcomed everyone and introduced the staff to the committee. He requested those who are testifying to (1) Sign in on the register, (2) Give written testimony to the Committee Secretary prior to the meeting, (3) Not read long testimony, but "hit the high points" and give the written text to the committee, (4) Coffee fund. He explained the procedures for the committees: (1) Quorum, (2) Proxies must be written, but must be date and bill/amendment specific. SENATOR CHRIS CHRISTIAENS voiced concern that amendments could change his vote on a bill. CHAIRMAN BENEDICT said if the proxy-holder feels uncomfortable voting on amendments, a request could be made to hold the vote open for another day. SENATOR FRED THOMAS made a motion for the vote to be held open if a proxy-holder does not feel comfortable voting on amendments. -

Theodore Olson, Conservative Stalwart, to Represent 'Dreamers' In

Theodore Olson, Conservative Stalwart, to Represent ‘Dreamers’ in Supreme Court By Adam Liptak • Sept. 26, 2019 o WASHINGTON — The young immigrants known as “Dreamers” have gained an unlikely ally in the Supreme Court. Theodore B. Olson, who argued for robust executive power in senior Justice Department posts under Republican presidents, will face off against lawyers from President Trump’s Justice Department in a case over Mr. Trump’s efforts to shut down a program that shields some 700,000 young undocumented immigrants from deportation and allows them to work. In an interview in his office, Mr. Olson said he had generally taken a broad view of presidential authority, particularly in the realm of immigration. “Executive power is important, and we respect it,” he said. “But it has to be done the right way. It has to be done in an orderly fashion so that citizens can understand what is being done and people whose lives have depended on a governmental policy aren’t swept away arbitrarily and capriciously. And that’s what’s happened here.” Mr. Olson has argued 63 cases in the Supreme Court, many of them as solicitor general under President George W. Bush. In private practice, he argued for the winning sides in Bush v. Gore, which handed the presidency to Mr. Bush, and Citizens United, which amplified the role of money in politics. But Mr. Olson disappointed some of his usual allies when he joined David Boies, his adversary in Bush v. Gore, to challenge California’s ban on same-sex marriage. That case reached the Supreme Court and helped pave the way for the court’s 2015 decision establishing a constitutional right to such unions. -

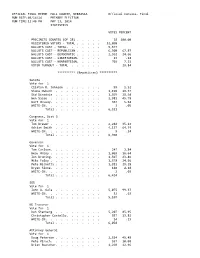

May 15, 2012 Primary Election

OFFICIAL RESULTS HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Canvas-Election Final RUN DATE:05/18/12 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:01 PM MAY 15, 2012 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 31,173 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 7,633 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 5,219 68.37 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,045 26.79 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 4 .05 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 355 4.65 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 24.49 ********** (Republican) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Newt Gingrich . 293 Ron Paul. 449 Mitt Romney. 3,406 Rick Santorum . 796 WRITE-IN. 57 Total . 5,001 United States Senator Vote for 1 Spencer Zimmerman. 29 Don Stenberg . 865 Jon Bruning. 1,669 Deb Fischer. 2,540 Pat Flynn . 121 Sharyn Elander. 28 WRITE-IN. 15 Total . 5,267 Representative in Congress Vote for 1 Adrian Smith . 3,975 Bob Lingenfelter . 1,180 WRITE-IN. 14 Total . 5,169 Hall County Public Defender Vote for 1 Gerard A. Piccolo. 4,144 WRITE-IN. 38 Total . 4,182 Hall County Supervisor Dist 2 Vote for 1 Daniel Purdy . 855 WRITE-IN. 5 Total . 860 Hall County Supervisor Dist 4 Vote for 1 Pamela Lancaster . 426 WRITE-IN. 7 Total . 433 Hall County Supervisor Dist 6 Vote for 1 Gary Quandt. 231 Robert M. Humiston, Jr.. 119 WRITE-IN. 2 Total . 352 ********** (Democratic) ********** President of the United States Vote for 1 Barack Obama . 1,447 WRITE-IN. 169 Total . 1,616 United States Senator Vote for 1 Larry Marvin . 64 Steven P. Lustgarten. 50 Sherman Yates . 32 Chuck Hassebrook . -

MIKE Mcgrath Montana Attorney General MICHEAL S

MIKE McGRATH Montana Attorney General MICHEAL S. WELLENSTEIN TAMMY K. PLUBELL Assistant Attorneys General 215 North Sanders P.O. Box 201401 Helena, MT 59620-1401 COUNSEL FOR STATE MONTANA FIFTEENTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT, ROOSEVELT COUNTY STATE OF MONTANA, ) ) Cause No. 1068-C Plaintiff and Respondent, ) ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF v. ) RESPONDENT’S MOTION TO ) DISMISS BARRY ALLEN BEACH’S BARRY ALLEN BEACH, ) PETITION FOR POSTCONVICTION ) RELIEF Defendant and Petitioner. ) ) The Attorney General of the State of Montana, on behalf of Respondent, State of Montana, submits the following Memorandum in Support of Respondent’s Motion to Dismiss Barry Allan Beach’s Petition for Postconviction Relief. INTRODUCTION The procedural history surrounding Beach’s case is epochal, involving proceedings in the Montana Supreme Court, federal district court, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and the Montana Board of Pardons and Parole (the Board). Many of the postconviction claims he now raises in this Court were previously raised in one form or the other in the Montana Supreme Court, Federal Courts, and most recently before the Board during his clemency proceeding. As demonstrated below, the Montana Supreme Court, the Federal Courts and the Board have unifiedly rejected Beach’s claims, including his claim that he is actually innocent of the Nees homicide. As the procedural MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT’S MOTION TO DISMISS BARRY ALLEN BEACH’S PETITION FOR POSTCONVICTION RELIEF PAGE 1 history below reflects, Beach has been afforded every avenue to prove he should not be held accountable for the brutal murder of Kim Nees, and Beach has soundly failed at every juncture. -

Conflicts of Interest in Bush V. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship Spring 2003 Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? Richard K. Neumann Jr. Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Richard K. Neumann Jr., Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally?, 16 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 375 (2003) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES Conflicts of Interest in Bush v. Gore: Did Some Justices Vote Illegally? RICHARD K. NEUMANN, JR.* On December 9, 2000, the United States Supreme Court stayed the presidential election litigation in the Florida courts and set oral argument for December 11.1 On the morning of December 12-one day after oral argument and half a day before the Supreme Court announced its decision in Bush v. Gore2-the Wall Street Journalpublished a front-page story that included the following: Chief Justice William Rehnquist, 76 years old, and Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, 70, both lifelong Republicans, have at times privately talked about retiring and would prefer that a Republican appoint their successors.... Justice O'Connor, a cancer survivor, has privately let it be known that, after 20 years on the high court,'she wants to retire to her home state of Arizona ... -

Research Report: Nebraska Pilot Test

6.1 Nebraska pilot test Effective Designs for the Administration of Federal Elections Section 6: Research report: Nebraska pilot test June 2007 U.S. Election Assistance Commission 6.2 Nebraska pilot test Nebraska pilot test overview Preparing for an election can be a challenging, complicated process for election offi cials. Production cycles are organized around state-mandated deadlines that often leave narrow windows for successful content development, certifi cation, translations, and election design activities. By keeping election schedules tightly controlled and making uniform voting technology decisions for local jurisdictions, States aspire to error-free elections. Unfortunately, current practices rarely include time or consideration for user-centered design development to address the basic usability needs of voters. As a part of this research effort, a pilot study was conducted using professionally designed voter information materials and optical scan ballots in two Nebraska counties on Election Day, November 7, 2006. A research contractor partnered with Nebraska’s Secretary of State’s Offi ce and their vendor, Elections Systems and Software (ES&S), to prepare redesigned materials for Colfax County and Cedar County (Lancaster County, originally included, opted out of participation). The goal was to gauge overall design success with voters and collaborate with experienced professionals within an actual production cycle with all its variables, time lines, and participants. This case study reports the results of voter feedback on election materials, observations, and interviews from Election Day, and insights from a three-way attempt to utilize best practice design conventions. Data gathered in this study informs the fi nal optical scan ballot and voter information specifi cations in sections 2 and 3 of the best practices documentation. -

Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS

OFFICIAL FINAL REPOR HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA Official Canvass- Final RUN DATE:05/16/14 PRIMARY ELECTION RUN TIME:12:46 PM MAY 13, 2014 STATISTICS VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 28) . 28 100.00 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 32,090 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 9,577 BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN . 6,500 67.87 BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC . 2,362 24.66 BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN. 13 .14 BALLOTS CAST - NONPARTISAN. 702 7.33 VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 29.84 ********** (Republican) ********** Senate Vote for 1 Clifton R. Johnson . 99 1.52 Shane Osborn . 1,196 18.37 Sid Dinsdale . 1,865 28.64 Ben Sasse . 2,981 45.78 Bart McLeay. 367 5.64 WRITE-IN. 3 .05 Total . 6,511 Congress, Dist 3 Vote for 1 Tom Brewer . 2,244 35.12 Adrian Smith . 4,137 64.74 WRITE-IN. 9 .14 Total . 6,390 Governor Vote for 1 Tom Carlson. 247 3.84 Beau McCoy . 1,069 16.64 Jon Bruning. 1,507 23.46 Mike Foley . 1,578 24.56 Pete Ricketts . 1,881 29.28 Bryan Slone. 140 2.18 WRITE-IN. 2 .03 Total . 6,424 SOS Vote for 1 John A. Gale . 5,075 99.37 WRITE-IN. 32 .63 Total . 5,107 NE Tresurer Vote for 1 Don Stenberg . 5,207 85.95 Christopher Costello. 837 13.82 WRITE-IN. 14 .23 Total . 6,058 Attorney General Vote for 1 Doug Peterson . 2,514 45.48 Pete Pirsch. 557 10.08 Brian Buescher. 1,269 22.96 Mike Hilgers . 1,183 21.40 WRITE-IN. 5 .09 Total . 5,528 State Auditor Vote for 1 Charlie Janssen . -

In God We Trust

IN THIS ISSUE • Money’s Motto “In God We Trust” is Constitutional • Court Voids Law on Animal Cruelty • Spousal Support Contract Enforceable Against Husband • Defective Sperm Could Not Be May 2010 Basis for Suit Money’s Motto “In God We Trust” is Constitutional SUMMARY: The statutes requiring that “In God We Trust” be Looking only at the motto Newdow opposes, and printed on U.S. paper money and stamped into U.S. coins do the wording of the Establishment Clause, his argument looks not violate the First Amendment because that motto is strong. Yet in 1970, the Ninth Circuit decided a case called ceremonial or patriotic and not an affirmative effort by the Aronow v. United States making the same essential argument government to advocate religious belief. The United States Newdow made here—that “In God We Trust” violates the First Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit decided Newdow v. Amendment’s Establishment Clause. In that case, the Ninth LeFevre on March 11, 2010. Circuit disagreed. Rather than a sincere statement or command of unified religious belief, the motto, ruled the court, was a BACKGROUND: Michael Newdow is an ordained minister in more generalized and symbolic slogan with a ceremonial or and founder of the First Amendmist Church of True Science, a patriotic purpose. Its function was rooted in tradition rather religion whose members believe that there is no god. Newdow than religion and the motto’s appearance on money did not has brought various lawsuits intended to end government impede people’s ability to believe or disbelieve according to practices that he and his church argue advance belief in a their own ideas and feelings. -

Newdow Calls for a New Day in Establishment Clause Jurisprudence: Justice Thomas's "Actual Legal Coercion" Standard Provides the Necessary Renovation James A

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 Newdow Calls for a New Day in Establishment Clause Jurisprudence: Justice Thomas's "Actual Legal Coercion" Standard Provides the Necessary Renovation James A. Campbell Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, James A. (2006) "Newdow Calls for a New Day in Establishment Clause Jurisprudence: Justice Thomas's "Actual Legal Coercion" Standard Provides the Necessary Renovation," Akron Law Review: Vol. 39 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol39/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Campbell: Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow CAMPBELL1.DOC 4/14/2006 1:14:41 PM NEWDOW CALLS FOR A NEW DAY IN ESTABLISHMENT CLAUSE JURISPRUDENCE: JUSTICE THOMAS’S “ACTUAL LEGAL COERCION” STANDARD PROVIDES THE NECESSARY RENOVATION I. INTRODUCTION Most Supreme Court cases fly under the radar of the national media. Occasionally, however, the media finds a case worthy of being thrust into the spotlight.1 In 2004, the Supreme Court faced such a case in Elk Grove Unified School District v. -

Bibliography on World Conflict and Peace

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 097 246 SO 007 806 AUTHOR Boulding, Elise; Passions, J. Robert TITLE Bibliography on World Conflict and Peace. INSTITUTION American Sociological Association, Washington, D.C.; Consortium on Peace Research, Education, and Development, Boulder, Colo. PUB DATE Aug 74 NOT? 82p. AVAILABLE FROMBibliography Project, c/o Dorothy Carson, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado 80302 ($2.50; make checks payable to Boulding Projects Fund) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 BC Not Available from !DRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; *Conflict Resolution; Development; Disarmament; Environment; *Futures (of Society); *Global Approach; Instructional Materials; International Education; international Law; International Organizations; *Peace; Political Science; Social Action; Systems Approach; *World Affairs IDENTIFIERS *Nonviolence ABSTRACT This bibliography is compiled primarily in response to the needs of teachers and students in the new field of conflict and peace studies, defined as the analysis of the characteristics of the total world social system which make peace more probable. The introduction includes some suggestions on how to use the bibliography, sources of literature on war/peace studies, and a request to users for criticisms and suggestions. Books, monographs, research reports, journal articles, or educational materials were included when they were:(1) related to conflict management at every social level,(2) relevant to nonviolence, and (3) classic statements in an academic specialization, such as foreign policy studies when of particular significance for conflict studies. A subject guide to the main categories of the bibliography lists 18 major topics with various numbered subdivisions. Th%. main body of the bibliography lists citations by author and keys this to the topic subdivisions. -

Teaching About Big Money in Elections: to Amend Or Not to Amend the U.S

Social Education 76(5), pp 236–241 ©2012 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching about Big Money in Elections: To Amend or Not to Amend the U.S. Constitution? James M. M. Hartwick and Brett L. M. Levy “Politics has become so expensive that it takes a lot of money even to be defeated.” — Will Rogers (1879–1935) Last summer, California and Massachusetts became the sixth and seventh states— activity is independent of the candidates’ along with Hawaii, New Mexico, Vermont, Rhode Island, and Maryland—to send a campaigns. These cases led to the rise resolution to the U.S. Congress calling for a constitutional amendment to (1) end the of “superPACs.” As long as they do not court’s extension of personhood rights to corporations, and (2) enable the government coordinate with campaigns and do not to definitively regulate campaign finances. This fall, with the bipartisan support of contribute directly to the candidates, its Democratic governor and Republican lieutenant governor, Montana is asking superPACs can raise unlimited funds voters to consider a referendum advising Montana’s congressional delegation to sup- from corporations, non-profits, unions, port such a constitutional amendment. Meanwhile, the current Congress has already and individuals and may spend those considered more than a dozen resolutions to amend the Constitution to strengthen funds to promote their favored political Congress’s ability to limit corporate funding of election activities, and 20 states have candidate or cause. In addition, non-prof- introduced similar resolutions.1 its, like “social welfare” groups (501 [c][4] s), may engage in unlimited non-coordi- Political support is growing. -

Hamdan V. Rumsfeld: Establishing a Constitutional Process

S. HRG. 109–1056 HAMDAN V. RUMSFELD: ESTABLISHING A CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 11, 2006 Serial No. J–109–95 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 43–111 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:01 Apr 27, 2009 Jkt 043111 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43111.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania, Chairman ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts JON KYL, Arizona JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware MIKE DEWINE, Ohio HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California LINDSEY O. GRAHAM, South Carolina RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN CORNYN, Texas CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois TOM COBURN, Oklahoma MICHAEL O’NEILL, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Democratic Chief Counsel and Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 11:01 Apr 27, 2009 Jkt 043111 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\HEARINGS\43111.TXT SJUD1 PsN: CMORC C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page Feingold, Hon. Russell D., a U.S. Senator from the State of Wisconsin, pre- pared statement ..................................................................................................